Economic Grand Rounds: Financial Disincentives for the Provision of Psychotherapy

During the past decade, treatment for most major mental disorders in the United States has been increasingly characterized by psychopharmacologic treatment (1,2). For example, Olfson and colleagues (2) studied national trends in the number of outpatients' being treated for depression between 1987 and 1997 and found a substantial increase in the proportion of individuals receiving antidepressant treatment (from 37.3 to 74.5 percent), whereas the use of psychotherapy declined (from 71.1 to 60.2 percent).

Psychosocial treatments, especially psychotherapy, are evidence-based treatments for most major mental disorders, including major depression (3), bipolar disorder (4), and schizophrenia (5,6). However, recent findings from a large national sample of psychiatrists participating in the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's (APIRE's) Practice Research Network (PRN) have shown that a significant proportion of psychiatrists' patients do not receive psychotherapy (7).

A number of supply and demand factors have been cited as reasons for the dramatic increase in the use of psychopharmaceuticals to treat most major medical disorders, including an increase of the pharmacologic options available (2), greater public acceptance of pharmacologic treatments (8), and a shift in the treatment for depression and anxiety disorders from the specialty mental health sector to the primary care sector, making pharmacologic treatment more likely (2). Also, financing can be a major barrier to psychotherapy. Current reimbursement rates have been reported to make the provision of psychotherapy not economically viable for many psychiatrists, who are the only specialty mental health providers licensed to prescribe pharmacologic treatments in most states.

The aim of this study was to assess the extent of current financial disincentives in the United States for the provision of psychotherapy by psychiatrists by comparing the fees that psychiatrists receive for providing psychotherapy with the fees that they receive for providing medication management.

Methods

We analyzed data on psychiatrists' mean discounted and undiscounted fees from a large, national random sample of 2,323 psychiatrists from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile (N=49,000) who were surveyed through the 2002 APIRE PRN National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (NSPP). The 2002 NSPP collected data on the practice and patient caseload characteristics of a representative sample of psychiatrists in routine practice in the United States between February and September 2002, with a 52 percent response rate (N=1,203). Data were collected by using paper-based and Web-based surveys, with a total of four survey waves that were used to achieve the final response rate. The SUDAAN statistical package was used to analyze the data and generate nationally representative estimates (9).

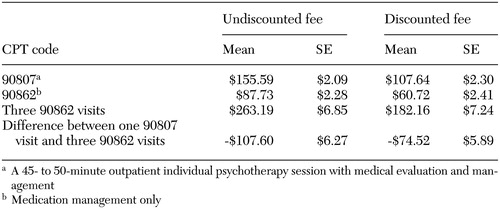

Our study compared the means of undiscounted and discounted fees for CPT codes 90807 (a 45- to 50- minute outpatient individual psychotherapy session with medical evaluation and management) and 90862 (medication management session only). Fees for one psychotherapy session with medical evaluation and management were compared with fees for three medication management sessions, because most medication management visits last 15 minutes (unpublished data, American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, 1999).

Results

As indicated in Table 1, findings from the 2002 NSPP indicated that in terms of discounted fees, psychiatrists who provide one 45- to 50- minute outpatient psychotherapy session with medical evaluation and management (CPT code 90807) earn $74.52 less per hour, or 40.9 percent less, than do psychiatrists who provide three 15-minute medication management sessions (CPT code 90862 for each visit). This financial disincentive for psychotherapy was also seen when psychiatrists' undiscounted fees were examined; psychiatrists who provide one 45- to 50- minute psychotherapy session with medical evaluation and management earn $107.60 dollars less per hour, or 40.9 percent less, than do psychiatrists who provide three 15-minute medication management visits.

Discussion

These findings raise two key questions. First, why are psychiatrists' fees structured in this manner? Second, what effect do financial disincentives for the provision of psychotherapy have on access to, quality of, and outcomes of treatment for mental disorders? Although empirical data about the factors driving the fee differentials and the financial disincentives for psychiatrists to provide psychotherapy are limited, there is speculation that the fees are structured in this manner to limit the supply and the overall use of psychotherapeutic treatments (10). Others have speculated that fees may be structured in this way so lower-cost, nonphysician mental health specialty professionals will provide psychotherapy, whereas higher-cost physicians will provide medication management (11). In addition, third-party payers may perceive psychopharmacologic treatments to be more effective and therefore may value them more highly than psychosocial treatments in terms of physicians' monetary fees. Consequently, third-party payers may structure the fees to encourage psychiatrists to provide psychopharmacologic treatment instead of psychotherapy. The fee structures may also reflect a greater emphasis on or confidence about a medical model in which mental disorders are managed with biomedical treatments and other somatic treatments considered more legitimate than psychotherapy (10). The emphasis on psychopharmacologic treatment is consistent with the strong bias that has been reported among third-party payers toward medical technologies and against cognitive tasks in medicine (12).

With respect to the effect of financial disincentives on access to, quality of, and outcomes of treatment, the data showed that psychiatrists' patients have more limited access to evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatments than to psychopharmacologic treatments (7). This finding provides evidence of a poorer quality care, because psychotherapy, like psychopharmacologic treatment, is considered to be an evidence-based treatment for most major mental disorders. In fact, evidence-based practice guidelines, which are considered a gold standard for assessing quality (13), recommend psychotherapy for patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and for indicated patients with major depression (3,4,5). In addition, because patients who receive both psychopharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy have better outcomes of treatment than do patients' receiving only psychopharmacologic treatment among patients with major depression (14), schizophrenia (6), anxiety (15,16), bipolar disorder (17), nicotine dependence (18), and personality disorders (19), the financial disincentives inherent in psychiatrists' fee structures may have serious, unintended consequences.

Our findings suggest that current health care financing policies that create financial disincentives for the provision of psychotherapy should be reconsidered, particularly in light of data that show inappropriately low levels of psychosocial treatment among most psychiatric patients. Substantial research shows that patients who receive adequate psychosocial treatment have better outcomes of care. Therefore, the financial disincentives for psychotherapy could ultimately result in significantly higher health care costs associated with longer-term treatment of patients with poorer outcomes, as well as immense societal and personal costs associated with mental illness that is not fully treated.

Acknowledgments

Development and support of the Practice Research Network (PRN) have been generously funded by the American Psychiatric Foundation, the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, the Center for Mental Health Services, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Members of the PRN contributed their time to participate in this study.

Dr. West is director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's (APIRE's) Practice Research Network, 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22209 (e-mail, [email protected]). All other authors are also affiliated with APIRE and the American Psychiatric Association. Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is the editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Fees charged for psychiatric services (data obtained from the 2002 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice)

1. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Pincus HA: Trends in office-based psychiatric practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:451–457, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203–209, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, 2nd edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2000Google Scholar

4. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 151(suppl 12):1–36, 1994Google Scholar

5. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(suppl 4):1–63, 1997Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. New findings from the PRN document limited access to psychotherapy and financing barriers. PRN Update, spring 2003, p 4Google Scholar

8. Langer F: Use of anti-depressants is a long-term practice. April 10, 2000. Available at http://abcnews.go.com/onair/worldnewstonight/poll000410.htmlGoogle Scholar

9. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Hunt PN, et al: SUDAAN User's Manual, release 7.0. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1996Google Scholar

10. Sharfstein SS, Goldman H: Financing the medical management of mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:345–349, 1989Link, Google Scholar

11. Goldman W, McColloch J, Cuffel B, et al: Outpatient utilization patterns of integrated and split psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Psychiatric Services 49:477–482, 1998Link, Google Scholar

12. Astrachan B, Sharfstein SS: The income of psychiatrists: adaptation during difficult economic times. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:885–887, 1986Link, Google Scholar

13. Lohr KN (ed): Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance, vol 1. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1990Google Scholar

14. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al: A comparison of nefazadone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. New England Journal of Medicine 342:1462–1470, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:2529–2536, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Mavissakalian M: Combined behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy of agoraphobia. Journal of Psychiatric Research 27(suppl 1):179–191, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

17. Clarkin JF, Carpenter D, Hull J, et al: Effects of psychoeducational intervention for married patients with bipolar disorder and their spouses. Psychiatric Services 49:531–533, 1998Link, Google Scholar

18. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2000Google Scholar

19. Kool S, Dekker J, Duijens IJ, et al: Efficacy of combined therapy and pharmacotherapy for depressed patients with or without personality disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 11:133–141, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar