Two Genealogies of Supported Housing and Their Implications for Outcome Assessment

Abstract

Drawing on ongoing fieldwork in New York City, the authors distinguish two "genealogies," or developmental traditions, of supported housing. "Housing as housing" originated in the mental health field to champion normalized, less-structured alternatives to clinically managed residential programs. "Integrated housing development" traces its origins to the movement to combat homelessness by preserving and creating affordable housing. The authors detail the distinctive premises, guiding concerns, and developmental logic of each lineage, contrasting the consumer advocate focus of the first genealogy with the emphasis on housing supply of the second. As housing and service investment strategies, the two approaches run different risks, speak to distinctive constituencies, and play to specific strengths. The authors argue that any attempt to take the measure of their success or to assess their comparative value as social investments must go beyond client outcome and come to terms with discrepant notions of the social good that they represent.

In 1990, Ridgway and Zipple (1) declared a paradigm shift in approaches to housing for people with serious mental illness, hailing supported housing—independent normal housing with flexible individualized supportive services—as an alternative to clinically managed residential programs. Field research in New York City, one of the sites for the current housing initiative of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), has identified two distinct traditions of practice that inform the supported housing movement and shape the character of local projects. In this article we argue that efforts to assess the effectiveness of supported housing must consider the distinctive premises of each tradition and the contrasting visions of social good that underlie them.

There are, in effect, two distinct genealogies of supported housing. The first hails from within the mental health field and advocates less-structured housing alternatives to clinically managed residential programs for persons with severe mental illness—"housing as housing." The second genealogy stems from the movement to arrest homelessness by preserving and increasing the supply of low-income housing— "integrated housing development." Although they overlap, each lineage has distinctive premises, guiding concerns, and developmental logic. Identifying these genealogical contrasts serves to highlight issues that more rigorous assessments of supported housing must address. Although our discussion necessarily reflects some singularities of the New York City setting, we believe that the strains analyzed here have bearing elsewhere as well.

SAMHSA's housing initiative was designed to test a model of supported housing against a continuum of residential programs for people with mental illness. Fidelity to the model in this multisite collaborative project largely reflects the influence of the first tradition, which has been well articulated by Ridgway and Zipple (1) and by Carling (2). However, in tight markets such as New York, persistent homelessness and the shortage of low-cost housing that fuels it has challenged providers to address not only the clinical paternalism of traditional mental health housing but also access to affordable units (3). The tensions between these competing priorities are handled differently by the two traditions. They imply markedly different social investment strategies as well.

The two traditions contrasted

Housing as housing supports its clients by improving the chances of otherwise disfavored tenants in tight housing markets—boosting their income, providing intensive housing search assistance, currying favor with selected landlords, guaranteeing monthly rent payment, vouching for the tenants' worth as good neighbors, and even pledging to mediate any disputes that arise. Organizational legitimacy is leveraged to advocate and broker access for clients. But although such programs increase demand, they remain hostage to the market, limited to existing housing stock.

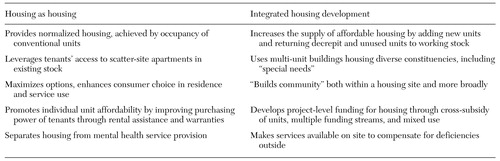

Integrated housing development responds to the challenge of housing unconventional tenants by addressing both demand and supply. Instead of pursuing openings within current inventories, this approach develops housing that includes mentally disabled adults—sometimes with children—among other "special-needs" tenants, such as former residents of homeless shelters, people with AIDS, and the working poor (3). Across projects, tenants with mental illness constitute a minority, although the percentages vary. (Parallels with employment programs for persons with severe mental disorders—especially the contrast between supported employment (4) and "social enterprises" (5)—are striking.) The cardinal concerns of the two approaches are contrasted in Table 1.

The two divergent approaches have different funding concerns as well. Mental health-based housing as housing focuses on securing rental income for individual clients as well as the service dollars required to coordinate and sustain access to community-based supports. Advocacy targets people with serious mental illness and pursues their right to housing, one consumer at a time; its chief constituency is the organized segment of mental health consumers. For integrated housing development, funding concerns span the range of housing and service development. Efforts focus on tapping new sources of financing—for example, adding job training to attract corporate giving. Advocacy appeals to the unmet needs of low-income renters and to neighborhood development. Constituencies of support include potential occupants of new apartments, co-investors in housing development, and neighborhood stakeholders.

Historical roots

Housing as housing originated as a consumer-initiated protest, not only of the overly structured, segregated housing offered by the mental health system as extended residential treatment but also of the logic linking housing access and tenure to clinical status and treatment compliance. Building on empowerment and community integration principles articulated by the psychiatric rehabilitation school, the advocates of housing as housing contended that normalized housing is fundamental to autonomy and self-determination. The social or treatment-related supports that might be required could be flexibly configured, ratcheted up or down as need demands.

By contrast, integrated housing development originated in efforts by advocates for the homeless poor to secure permanent alternatives to shelters by combining community development with low-income housing production. Affordability was key, not only because formerly homeless persons were poor but also because the issue of costs provided common cause with other "housing-needy" groups. Developing housing and making it affordable required complicated financial packaging. Low-income-housing tax credits, limited syndication, dedicated rehabilitation streams, and rental certificates are among the strategies tapped in efforts to build more housing.

Because social isolation and stigma also frequently accompanied homelessness, project developers commonly came to view community building as part of their task. When mental health service providers partnered with housing developers, they were able to offer their clients more heterogeneous, "normal" housing settings than mental health dollars alone could have provided. Including tenants with severe mental illness not only enhanced rental income—because of larger disability benefits—but also served the cause of integration. Planned diversity thus became both a fiscal necessity and a social desideratum.

The two supported housing models thus diverge markedly in how they approach social change. Given decades of extreme housing scarcity in many urban areas, housing as housing champions the interests of a group whose mental illness disadvantages them in the scramble to obtain and hold onto housing. It serves its clients by providing support to maximize their individual advantage in the existing housing market. With roots in local organizing, integrated housing development advances the interests of community development. It pushes a mixed agenda of housing creation and community building, negotiated with an eye to fiscal viability as well as social utility. Whereas the first approach addresses the competitive position of its constituents with respect to a limited good, the second augments the supply, changing the structure of possibility for a variety of formerly excluded subgroups.

Client-centered housing as housing can customize its interventions more easily—for example, deploying service resources when needed to support tenants whose active substance use or disruptive symptoms make them poor prospects for a fledgling community. Integrated housing development must attend to the viability of a building's tenancy as a whole, and may set a higher threshold of stability for those admitted, while still ensuring that specialized services are on hand should stability prove fragile.

Premises and practices

The separate histories and conceptual underpinnings are not always evident when the two supported housing approaches are implemented in real-world settings. A common commitment to extending normalized housing options for persons who are unable to crack the housing market on their own, and the similar circumstances of housing scarcity they face in their efforts to make good on this commitment, can mute the contrasts. But once the premises of each approach are recalled, certain practices and concerns follow as a matter of course—the contrast here is the emphasis of housing as housing on the well-being of an individual client versus the extended interest of integrated housing development in the welfare of a building and neighborhood. Otherwise obscure tensions—for example, the prominence of consumer "choice" for housing as housing compared with the concern of integrated housing development with achieving a workable balance of tenants in a building—become clearer once their rationales are explained.

Visibility of effort

In New York, the two approaches imply different levels of visibility—and political exposure—as well. Housing as housing matches needy tenants with existing vacancies, courting landlords by assuring rent payment and intervention should difficulties arise. The risks, like the tenants, are dispersed, and a mismatch between tenant and building (or neighborhood) can be handled by finding accommodations elsewhere. This approach may inhibit a strong identification between the agency and the local community, but it also extends services to those who fail housing-readiness tests of stability and sobriety and who would otherwise face long periods in transitional accommodations.

When integrated housing development invests capital and credibility in large-scale projects—such as the New York agency that took on a huge decrepit hotel and turned the building into the pride of the neighborhood—the match of person to place looms larger, requiring more attention to the impact of individuals on the larger tenant community and culture. Although the diversity of tenant constituencies and the availability of specialized services allow such projects to accommodate people with severe psychiatric disorders (30 percent of tenants at this New York site), a concentration of tenants whose sobriety slips or whose functioning deteriorates may threaten a project's viability and undermine its claim to provide normalized housing.

Thus tenant recruitment occurs with an eye to a building's current complement of persons who are active drug users or who have unstabilized psychotic symptoms, which sometimes allows for accepting high-risk tenants but often puts a premium on indicators of stability—for example, the time a prospective tenant has been drug free and whether he or she takes medications that control symptoms. Investment in community, that is, means more stringent screening of prospective tenants and imposes stricter limits on a building's tolerance of disruptive extremes.

The implications of the contrasts in visibility and selection are not well understood. How mentally ill tenants who are housed in the two types of programs actually differ is an empirical question that would need to be considered in any effort to compare outcomes of the two approaches (6). Empirical research is also needed to determine, for example, whether the two approaches enjoy differential success in neutralizing stigma. Are there differences in the way neighbors view and treat the beneficiaries of each approach? The low profile of housing as housing favors behind-the-scenes intercessions on behalf of individual tenants on an as-needed basis to address specific problems. Tenants can interact with neighbors and local merchants without having their status as mental health service consumers betrayed by their address. "Success" under such circumstances tends to be invisible. Although an antistigma strategy that depends on consumers' ability to "pass" in normal community life may inhibit participation in high-profile advocacy campaigns, troubleshooting for individual tenants could be considered a form of unobtrusive neighborhood education.

Sheer size and visibility draw attention to integrated housing development projects in ways that housing as housing would find unwanted. That reality makes deliberate stigma-combating efforts part of the modus operandi of such programs, which gamble that a building's good reputation may blunt the edge of the prejudice extended to some of its occupants. In setting aside units for discrete groups, integrated housing development cultivates the diversity that old-time urban planners took to be the keystone of neighborhood vitality (7), while reducing social distance as a fact of everyday life. Because stigma relies on stereotypes that do not readily withstand such exposure, the face-to-face interactions built into the design quietly enhance more explicit efforts to enhance a building's reputation.

The two approaches to supported housing demand very different neighborhood commitments. For housing as housing, neighborhood conditions are largely given; the unit of interest is the individual rental property. In its bid for neighborhood support, integrated housing development must be more attuned to context. Enhancing local quality of life benefits tenants with severe mental illness, along with others. The assessment dilemma is plain: although measures of how well tenants with mental illness are doing can be used to determine the relative merits of the two approaches as mental health investments, they may be inadequate for appraising such ventures as social goods. In taking aim at homelessness and poverty more generally, integrated housing development may demand a different yardstick for measuring its impact.

Community integration

It should be emphasized that both variants of supported housing are committed to providing an essential survival good in as normalized and destigmatized a setting as possible, although meanings of and strategies for community integration differ (6). Housing as housing approaches the task by playing the market as savvy brokers, trusting to the natural—if income-mediated—distribution of the available units in "scatter-site" fashion. The support services that tenants may need are supplied by existing sources; where gaps exist, targeted supplements may be contracted for. Tenacious case management may be part of the package, usually in an explicitly negotiated format (8). Although, in practice, such programs may develop specialized services (modified assertive community treatment teams in one New York program), these services are not based at the housing sites. By contrast, integrated housing development courts normalcy by building diversity into project design, actively promoting micro-communities rather than relying on tenant initiative and the fortuitous supply of local raw materials. By locating mental health and support services in the immediate environs, where they may be used by any of a project's tenants, such programs enable tenants to control the terms of their treatment by ensuring access while making participation optional. Community-based agencies with experience providing low-demand mental health and support services in nonclinical settings usually anchor on-site service efforts.

Strikingly different notions of "community" are at work here. For housing as housing, making your way into ordinary housing is a critical first step toward community integration. The deal can be a lean one: once rehoused, the tenant is subjected neither to the enforced social contact of institutional settings nor the anomie of the streets or shelters; community is essentially what one makes of it. For Carling (2) and other advocates, "tenancy in a personally valued environment" provides a base from which to pursue "the redevelopment of informal social support networks including renewed family contact." Professionals are enjoined to "develop a variety of creative ways to help these individuals gain access to the richness of community life," notably by incorporating consumers into their own personal networks. Community integration should be sought "only within the context of real, in-depth relationships with other people…one person at a time." Should "the richness of community life" prove elusive, such programs may relax the stricture against organized activities by offering agency facilities for tenants to gather, socialize, and pursue hobbies or interests.

By contrast, integrated housing development adopts social engineering in pursuit of contrived communities. Its advocates insist that addressing quality-of-life issues requires consideration of what sort of social environment might best enable persons with severe mental disorders to explore the possibilities of community. To date, the multiunit buildings created by integrated housing development offer tenants a relatively secure community of diverse members who have already been vouched for. Such programs promote community building by using designs such as user-friendly lobbies, rooftop gardens, on-site amenities, and relegation of service providers' offices to less visible areas of the building, along with active organizing efforts such as hiring a community organizer and fostering tenant councils (3).

Reprise

Underlying the diverse issues confronting supported housing programs—for example, whom to target for housing, a program's neighborhood role and commitment, and its approach to stigma—are two contrasting approaches. The first approach stresses empowering individuals to make their own way in mainstream society; the second actively cultivates communities of diverse though marginalized tenants. Choice and the opportunity to create a personalized home bulk large in the developmental ethic of housing as housing, which emphasizes the therapeutic principle of self-determination. Indeed, for some of its advocates, "the primary goal of supportive housing should not be the development of units of housing or the delivery of units of services . . . [but] to empower each individual to develop a home and a sense of belonging in his or her community" (9).

From the perspective of housing as housing, the urgent-business approach of integrated housing development risks substituting quantity (new units built) for quality (empowered consumers making their own way); values efficiency over attending to the consumer's voice; and squanders an opportunity to collapse outmoded hierarchical arrangements. For partisans of housing as housing, quality of life is fundamentally an issue of personal efficacy— "controlling access to personal space…being able to alter one's environment and select one's daily routine, and…having personal space that reflects and upholds one's identity and interests." They worry about the potential of housing development to deflect empowerment efforts and argue that money spent acquiring and renovating dilapidated properties could have been more efficiently spent on targeted rental vouchers and support (9).

This utilitarian calculus does not sway advocates of integrated housing development. Chastened by three decades of a steadily worsening housing market, they see an emphasis on personalizing individual space as naive. In their view, restricting rehousing efforts to consumers of mental health services is unfairly targeted, perpetuating a "special pleading" approach to advocacy— "My clients are more needy than yours"—that undermines the solidarity needed for intelligent neighborhood planning. At a time of growing need and shrinking programs, when the lines dividing those who are at risk and those who are disabled are increasingly blurred, integrated housing development contends that efforts to select and serve those with psychiatric diagnoses as the truly needy are shortsighted. Making common cause with other aggrieved groups to address the affordable-housing shortage, and doing so in a way that addresses both housing stock and neighborhood quality, is the larger social good it embraces.

Policy implications

The two approaches to supported housing diverge markedly in the investment strategies they suggest for mental health dollars. Housing as housing advocates client-based services, earmarked housing subsidies, and protected access. It offers speed, the efficiencies of targeted action, and economies of a proven format. Integrated housing development champions a cross-system approach, with set-asides for persons with diagnoses. Although the former promises short-term cost savings, it confronts the long-term viability of queue jumping. This approach maneuvers its clients to the front of the line for what is ultimately a scarce resource (10), risking the resentment of competing (and equally needy) groups (11). Clinicians with long histories of mental health advocacy have recently questioned the equity implications of seeking preferential consideration for groups defined by their mental health needs (12). In an era in which entitlements of all sorts are under scrutiny, promoting the special claims of some stands in marked contrast with a strategy of forging alliances with other disadvantaged groups.

Still, low-income housing development can be an uncertain undertaking, subject to potentially derailing contingencies. Advocates of housing as housing argue pointedly that mental health dollars are limited and that it is a move of ill-timed generosity to propose extending these dollars to categories of need that are only distantly related to traditional provinces of concern. At a time when bureaucratic boundaries are being redefined and when control of dollars is the surest guarantor of a claim-stake, earmarking mental health dollars for mental health clients makes tactical sense, however absurd it may appear to people whose needs fail to conform to programmatic contours.

The differences dividing the two lineages of supported housing should not obscure their substantial commonalities. But just as efforts to expand housing capacity should not be judged by numbers alone, neither should concern with the predicament of people with severe mental illness set the only criteria for assessing a project's value. Obviously, such an approach complicates outcome measurement and wreaks havoc with bureaucratic boundaries. However, such mischief may be both necessary and salutary if we are properly to take the measure of public dollars as social investments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ilysa Berg, B.A., Alicia Diaz, B.A., Claire Haiman, B.A., Kinjia Hinterland, M.P.H, John Jost, Ph.D., Nicole Laborde, M.P.H., David Vine, B.A., Tony Hannigan, M.S.W., Priscilla Ridgway, B.A., and Sam Tsemberis, Ph.D.

Dr. Hopper is affiliated with the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, 140 Old Orangeburg Road, Orangeburg, New York 10962 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Barrow is affiliated with the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Both are with the New York City Housing Alternatives Project.

|

Table 1. Comparison of two approaches to supported housing

1. Ridgway P, Zipple AM: The paradigm shift in residential services: from the linear continuum to supported housing approaches. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13:11-31, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Carling P: Return to Community: Building Support Systems for People With Disabilities. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

3. Houghton TA: Description and History of the New York/New York Agreement to Housing Homeless Mentally Ill Individuals. New York, Corporation for Supportive Housing, 2001Google Scholar

4. Becker DR, Drake RE, Farabaugh A, et al: Job preference of clients with severe psychiatric disorders participating in supported employment programs. Psychiatric Services 47:1223-1226, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Emerson J, Twersky F: New Social Entrepreneurs. San Francisco, Roberts Foundation, 1996Google Scholar

6. Wong YLI, Solomon PL: Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: a conceptual model and methodological considerations. Mental Health Services Research 4:13-28, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Jacobs J: The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, Vintage, 1961Google Scholar

8. Diamond RJ: Coercion and tenacious treatment in the community: applications to the real world, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

9. Ridgway P, Simpson A, Wittman FD, et al: Home making and community building: notes on empowerment and place. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:407-418, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Hopper K, Baumohl J: Held in abeyance: rethinking homelessness and advocacy. American Behavioral Scientist 37:522-552, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Lovell AM, Cohn S: The elaboration of "choice" in a program for homeless persons labeled psychiatrically disabled. Human Organization 57:8-20, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Rosenheck R, Bassuk B, Salomon A: Special populations of homeless Americans, in Practical Lessons: The 1998 Symposium on Homelessness Research. Edited by Fosburg L, Dennis D. Washington, DC, US Department of Housing and Urban Development and US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar