Datapoints: Use of a Behavioral Health Web Site and Service Utilization

Although some regard mental health Web sites as a useful adjunct to therapy, a primary concern has been the use of such sites as a "Band-Aid," which may delay or prevent consumers from obtaining much-needed mental health care (1,2). This study examined whether allowing free access to a behavioral health care Web site would affect the use of mental health services in a random sample of 1,806 adults who were enrolled in United Behavioral Health, a national managed behavioral health organization, and who had accessed their benefits for the first time.

Members were randomly assigned to a group that received free and confidential access to the Web site (N=1,211) and a control group that had no access (N=595). Members of the first group were informed about their access by mail during the week of July 9, 2001; the second group received no information. Use of mental health services was tracked over a four-month period. Of the 1,211 members with access, 54 (4.5 percent) signed on to the Web site's home page at least once during the four months.

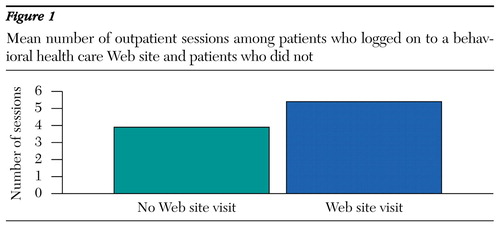

Neither Web site access nor logging on to the site were predictive of a mental health visit. No significant difference was found between the group that had Web site access and the control group in the time from the date the member requested an authorization to see a mental health clinician and the date of the first mental health visit. Access to the Web site was not associated with the number of outpatient sessions in the following four months. However, as shown in Figure 1, patients who visited the Web site within four months of being given access subsequently had more outpatient sessions than those who had access but did not visit the site (F=5.33, df=2,1,803, p<.02). Furthermore, neither receiving access nor visiting the Web site was associated with the total cost of all mental health services received between July and November 2001.

Providing members of a managed behavioral health organization with free Web site access did not appear to promote or delay their use of mental health services. Among members who had access, those who visited the site had more outpatient sessions than those who did not. This finding suggests two possibilities. First, the material on the Web site may have led members to obtain treatment or, if they were already receiving services, it may have reinforced their commitment to treatment. Alternatively, those who visited the site may have had more severe conditions or perceived a greater need for help and may have been more likely to use more treatment sessions.

Although the data we examined did not provide more specific information about these individuals, access to the Web site may have been a useful adjunct to outpatient treatment. This study provided some evidence that contrary to the belief held by some mental health clinicians, use of a mental health Web site does not promote or delay treatment seeking and does not seem to increase the cost of services. On the other hand, Web sites offered by managed behavioral health care organizations may provide useful information about benefits, network clinicians, and mental health topics.

The authors are affiliated with United Behavioral Health, 425 Market Street, 27th Floor, San Francisco, California 94105 (e-mail, [email protected]). Harold A. Pincus, M.D., and Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., are editors of this column.

Figure 1. Mean number of outpatient sessions among patients who logged on to a behavioral health care Web site and patients who did not

1. Christensen H, Griffiths K: The Internet and mental health literacy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:975-979, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Budman SH: Behavioral health care dot-com and beyond: computer-mediated communications in mental health and substance abuse treatment. American Psychologist 55:1290-1300, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar