An Analysis of the Definitions of Mental Illness Used in State Parity Laws

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Thirty-four states have enacte mental health parity laws that require a health plan, insurer, or employer to provide coverage for mental illness equal to that for physical illness. This study analyzed definitions of mental illness used in state parity laws, identified factors influencing the development of these definitions, and examined the effects of different definitions on access to care for persons with mental illness. METHODS: Specific language in each state's parity legislation was analyzed. Interviews were conducted with policy makers, mental health providers, advocates, and insurers to determine factors influencing a state's definition. Current definitions of mental illness used in the clinical literature and in federal policy were reviewed and compared with definitions used in state parity laws. RESULTS: The definitions of mental illness used in state parity legislation vary significantly and fall into one of three major categories: "broad-based mental illness," "serious mental illness," or "biologically based mental illness." To define each of these categories, state legislatures do not rely on clinically accepted definitions or federal mental health policy. Rather, influenced by political and economic factors, they are developing their own definitions. CONCLUSIONS: Definitions of mental illness in state parity laws have important implications for access, cost, and reimbursement; they determine which populations receive a higher level of mental health services. Future research must qualitatively examine how state definitions affect the use and cost of mental health services.

As part of an interdisciplinary research team, we analyzed parity laws in 34 states and concluded that there is no single model of state mental health parity (1). In this paper we focus specifically on how states define mental illness in parity laws. We review how mental illness is defined by clinicians and in federal mental health policy and compare these definitions with those used in parity statutes. We then analyze variations in state definitions, identify factors that account for the variation, and discuss how the variation may affect access to and use of mental health services. Finally, we discuss the financial consequences of reimbursing mental health care by diagnosis, including the potential for provider upcoding.

Background

During the early 1980s, costs for treating mental disorders were rising at twice the rate of other health care costs. Many employers responded by limiting the number of inpatient days and imposing 50 percent coinsurance for outpatient visits. A 1997 Mercer/Foster Higgins survey of employer-sponsored health plans found that 75 percent of insurance plans placed greater restrictions on behavioral health coverage than on general medical coverage (2).

In the early 1990s, many states addressed the problem of limited mental health coverage by passing mental health parity laws. The National Advisory Mental Health Council defines parity as "insurance coverage for mental health services that is subject to the same benefits and restrictions as coverage for other health services" (3).

At the federal level, Congress enacted and President Clinton signed the 1996 Mental Health Parity Act, which requires group health plans with more than 50 employees to offer the same annual and lifetime spending caps for mental health and medical benefits. Insurers are exempt if parity increases costs by more than 1 percent after six months. Enactment of mental health parity at the federal level symbolized the prioritization of mental health care and energized state parity efforts (4). Before 1996 only five states—Maryland, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Maine, and Minnesota—had adopted parity laws. After the 1996 law was passed, 29 states passed parity bills with stronger provisions than the Mental Health Parity Act.

Methods

Our research proceeded in three steps. First, we analyzed the definition of mental illness used in 34 states' parity laws. We focused on how the statutory definition of mental illness was introduced and amended during the legislative process. Second, we reviewed the definitions of mental illness used in the clinical literature and in past federal mental health legislation. Finally, we conducted more than 75 interviews between March 1999 and June 2001, using a standard questionnaire. Interviewees included representatives from the office of the sponsor of a state parity bill, relevant Congressional committees, mental health advocates and professional groups, employer groups, local health plans, and the State Department of Insurance.

Results

Clinical and federal definitions

The clinical literature uses two main classification systems to define mental illness. The first system, described in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), is the one most widely accepted by the clinical community. DSM is a multiaxial classification system that defines a mental disorder as "a clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual,…is associated with present distress…or disability…or with a significant increased risk of suffering." DSM groups disorders by symptom clusters and differentiates between normality and psychopathology on the basis of the duration and severity of symptoms. For reimbursement coding, clinicians also use the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). ICD is "crosswalked" with DSM, meaning that DSM diagnoses are included in ICD (5).

The second classification system conceptualizes mental illnesses as "brain disorders" and is based on the hypothesis that disruptions in brain function lead to mental illness. Rather than relying on descriptive criteria such as those in DSM, biopsychiatrists classify mental disorders on the basis of heritability, biochemical markers, and anatomical lesions (6). The appropriateness of biological psychiatry's classification system continues to be actively debated. Most clinicians agree that the use of purely biological criteria is too limiting, because no single gene or underlying brain lesion has been found for any disorder except Alzheimer's disease (7).

Historically, federal mental health policy has used the term "mental illness" but has not explicitly defined it. Instead, the laws leave the definition up to insurers or the agency responsible for implementation of the legislation. Traditionally, when the term "mental illness" has been used in federal legislation, it has been interpreted to include all disorders in DSM.

Policy makers and clinicians have attempted to identify seriously mentally ill populations in order to target service programs and epidemiological studies. Early definitions of seriously mentally ill populations were based on residence in state institutions. After deinstitutionalization the definition needed to be reformulated. Current definitions used in the clinical literature and federal policy are not identical, but all use a combination of criteria that address diagnosis, functional disability, and the duration of illness (8,9,10).

Definitions in state parity laws

Our analysis of state parity laws found that, except for three states, each state uses one of three statutory terms to define mental illness. The three exceptions are Minnesota, Indiana, and New Mexico, which leave the definition of mental illness up to individual health plans. These states were not included in our analysis, because the definitions that individual health plans use depend on how these states implement parity.

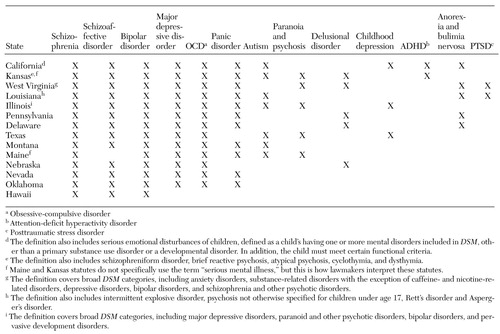

The three statutory terms used to define mental illness in state parity legislation are "broad-based mental illness," "serious mental illness," and "biologically based mental illness." The definition of broad-based mental illness is the most comprehensive and generally covers all disorders in DSM-IV. Table 1 lists the ten states that require parity for broad-based mental illness. Four of these states— Connecticut, Kentucky, Rhode Island, and Utah—exclude specific diagnoses, most notably children's diagnoses such as learning and conduct disorders.

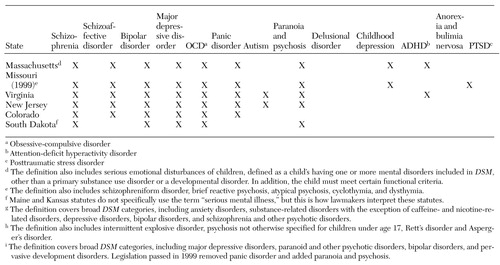

The terms "serious mental illness" and "biologically based mental illness" are more restrictive and include three or more DSM disorders. Table 2 lists the 14 states that require parity for serious mental illness. Table 3 lists the six states in which parity for "biologically based" mental illness has been implemented.

Discussion

The tables highlight the wide variation found in the definitions of mental illness used in parity laws. This variation leads to the question of where states are getting their definitions of mental illness. Traditionally, states have relied on federal policy or clinical experience as guidelines when enacting mental health policy. However, when we compared the definitions of mental illness used in the clinical literature and in federal policy with those used in state parity laws, the only agreement we found was with the seven states that include all disorders in DSM. States that use "serious mental illness" as the definition are not using the accepted combination of criteria addressing diagnosis, duration, and disability. Instead, lawmakers include only diagnosis. Finally, states that use "biologically based mental illness" as the definition are charting new territory because the term has never been used in federal legislation and has no accepted clinical definition.

Factors influencing state definitions

How are states choosing which disorders to cover at parity? From our interviews and literature review, we determined that several factors are influential, including the ideologies of advocacy groups and parity opponents, cost, and political necessity. States rarely, if ever, considered disease prevalence, needs-based studies, and clinical judgment. In our opinion the definitions that states use result from a political and economic process involving mental health advocates and providers, pro- and antiparity legislators, insurers, and employers.

More than 90 percent of the people we interviewed agreed that mental health advocacy and the interests of providers most strongly influenced how mental illness is defined in a parity bill. There are two primary mental health advocacy groups: the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) and the National Mental Health Association (NMHA). In most states, either NAMI or NMHA have led the parity coalition. Advocates often drafted the bill, worked closely with the legislative sponsor, wrote critical testimony, and organized grassroots support.

NAMI and NMHA each conceptualize mental illness differently. NAMI emphasizes the importance of biological factors in the etiology of serious mental disorders and advocates for "equitable services for people with severe mental illnesses, which are known to be physical brain disorders" (11). NAMI promotes ending discrimination and demanding fair legislative policies for "priority populations with serious mental illness." Priority populations include those with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder and other severe anxiety disorders, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

In contrast, NMHA defines mental illness broadly, addressing a person's ability to function rather than his or her diagnosis. NMHA has historically focused on the prevention of mental and emotional disabilities and has developed an extensive Community Prevention Services Program (12). In our analysis, we found that more than 85 percent of NAMI-drafted bills used the "biologically based" or "serious mental illness" definitions of mental illness, whereas 100 percent of NMHA-drafted bills used the "broad-based" definition.

The two main provider organizations involved with parity are the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association. The former works with NMHA to advocate for broad-based parity. District branches of the American Psychiatric Association in each state work with both NMHA and NAMI, writing testimony and educating providers. At the national level, the American Psychiatric Association's Institute for Research and Education is conducting a study examining the effects of parity on the federal employee health benefits program (13).

State mental health advocacy and provider groups participate in social learning in the sense that they copy definitions of mental illness from existing state parity laws. Advocates report that using a definition of mental illness that is already being implemented is an important factor in convincing lawmakers that the definition is both practical and cost-effective. For example, the Montana chapter of NAMI drafted parity legislation based on language developed by the New Hampshire chapter of NAMI for the bill that was successful in becoming New Hampshire's parity law. Similarly, the legislation drafted by Connecticut and New Jersey legislators in cooperation with local NAMI chapters used language developed by Ken Lieber-toff, director of the Vermont Mental Health Association and author of Vermont's successful bill.

Cost was the second most influential factor cited by interviewees as shaping the definition of mental illness. Two major organizations, the Chamber of Commerce and the National Federation of Independent Business, strongly argued that mandates requiring coverage for all DSM disorders would lead to uncontrolled demand for mental health services and would cause businesses to drop health insurance altogether, increasing the number of uninsured people by almost 6 percent (14). In Hawaii, the only state requiring employers to provide health insurance, lawmakers narrowed the definition of mental illness in the mental health parity bill to three specific illnesses chosen by local insurers—schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder.

Third, the political strategy that has been used to "sell" parity has influenced the definition of mental illness. A biologically based definition of mental illness allows advocates to frame parity legislation as antidiscrimination legislation. Using positron emission tomography (PET) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that shows obvious lesions, researchers have testified before Congress and state legislatures that mental illness is directly linked to brain dysfunction. Faced with such testimony, policy makers can hardly argue that mental illness is not a brain disorder and that it should not be treated like diseases of the heart or lungs.

Finally, political necessity has shaped the definition of mental illness. Many of the people we interviewed faced a "take it or leave it" scenario, in which definitions of mental illness were narrowed to increase the probability of a bill's passage. For example, risk-averse politicians in antiregulation states such as Delaware and South Dakota preferred an incremental approach, which made narrow bills more attractive. New Jersey, having failed to pass three successive parity bills that used a broad-based definition of mental illness and facing a fourth defeat, pared the definition of mental illness down to eight diagnoses. In such cases, advocates strategize that establishing limited parity is critical to paving the way for broader bills. For example, Connecticut passed a bill in 1997 that used the biologically based definition, and in 1999 the bill was amended to cover broad-based mental illness.

Implications of variation

Why should clinicians and policy makers be concerned about the definitions of mental illness used in parity laws? We could simply agree that a state's passage of parity legislation will increase access to mental health care for the privately insured population, regardless of the specific illnesses covered in the bill. However, this is not necessarily true—definitions matter, and research supports the fact that definitions matter. Narrow and colleagues (15) applied three different clinical definitions of serious mental illness to the same population and found that the prevalence rates ranged from 3 percent to 23 percent.

Definitions used in parity laws have important access and cost implications, which are discussed below.

Access implications. Access to mental health services refers to the ability to obtain treatment for mental health disorders with appropriate professionals. An important determinant of access is the level of copayments, deductibles, and limits, which are all affected by parity laws (5). Under all federal and state parity laws, insurers pay for care after a mental disorder is diagnosed. Thus the definition of mental illness used by an insurer is critical. To be considered for parity coverage, a person must qualify for a diagnosis included in the parity law in his or her state. Without such a diagnosis, it is unlikely that state laws will mandate insurers to cover any minimum level of treatment.

When states use political and economic criteria to choose reimbursable DSM diagnoses, some populations in need of services will be missed. DSM was not designed to prioritize the needs of mentally ill populations. DSM outlines a clinical classification system that is based on a continuum of self-reported symptom clusters, not specific functional limitations. This makes the line between a disorder considered "serious" and one considered "not serious" arbitrary (16).

For example, the DSM criteria for major depression, considered a "serious mental illness" in state parity laws, can be met by having five of nine possible symptoms over a two-week period. Kendler and Gardner (16) found that these DSM criteria create an arbitrary cutoff on a continuum of depressive symptoms and do not accurately reflect the severity of illness. A study by Regier and colleagues (17) found that simply changing the order of the questions used in epidemiological survey instruments can affect the prevalence rate for DSM disorders.

Patients with subthreshold disorders—that is, those who have symptoms that do not meet DSM criteria—may have significant disability, but they are denied access to care under limited-parity bills. For example, minor depression is defined as two or more depressive symptoms lasting at least two weeks but not meeting criteria for major depression or dysthymia (18). A person with minor depression who lives alone in a dilapidated apartment may have more need of hospitalization than a person who has major depression and a supportive family (19). Among persons with subthreshold depressive symptoms, the disorder progresses if it is untreated. Wells and colleagues (20) showed that 54 percent of people with dysthymia developed major depression during a two-year follow-up period.

A second population missed by limited parity legislation is children. In 1982 Knitzer (21) found that two-thirds of the three million American children with serious emotional disturbances were not receiving needed services. The report from the 2001 Surgeon General's Conference on Children's Mental Health (22) highlighted this crisis and noted that most children with serious emotional disturbances who had private insurance were not receiving professional help. It is clear that children's mental health is an area in which parity laws can have an important impact.

Unfortunately, in states in which parity legislation has a limited definition of mental illness, it is almost impossible for a child to meet the criteria for a diagnosis that requires treatment under the law. Few children can verbalize the feelings that would lead to a diagnosis of more serious DSM disorders. In addition, children's complex developmental changes pose diagnostic challenges—the expression and course of a disorder in a child and an adult are very different (23).

Two states, California and Massachusetts, have addressed this lack of coverage by including children's parity provisions. To qualify for coverage at parity, a child must be diagnosed as having any DSM-IV disorder (excluding developmental and substance use disorders) and meet certain functional criteria, such as being at risk of removal from the home and at risk of violence. These new definitions broaden the scope of impairment and allow children to be treated earlier in the course of illness.

Cost implications. Untreated mental disorders not only incur costs to affected individuals but also have high social costs. Many factors contribute to these indirect costs, including lost work productivity, homelessness, and expenses to the criminal justice system. It has been estimated that lost productivity alone constitutes 45 percent of the total economic costs of mental disorders (24).

In the evaluation of parity, how do definitions of mental illness affect indirect costs? Theoretically, narrower definitions lead to a higher burden of untreated illness and result in higher indirect costs. Several studies of depression indicate that subthreshold symptoms result in economic burden and that treatment can restore occupational functioning (25,26,27).

Implications for behavioral health providers. The regulation of mental health treatment is not new. Previous mental health legislation excluded certain treatments or limited the number of visits. However, in past legislation eligibility for coverage was not determined by diagnosis. Linking diagnosis to reimbursement was first used in the early 1980s, when Medicare began prospective reimbursement based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). Under this system, Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of the "relative weight" of the DRG—that is, its overall complexity.

DRG-based reimbursement assumes that hospitals and physicians accurately code a patient's course of illness in the hospital. However, Hsia and associates (28) found that the average hospital incorrectly codes a patient's DRG about 21 percent of the time and that these DRG changes did not occur randomly. More than 60 percent of the miscodings favored the hospital. In some cases, the codes used in reimbursement claims indicated more serious conditions or more intense treatment than was documented in the medical record—a phenomenon known as "DRG creep."

Mental health parity legislation introduces the possibility of DRG creep. The diagnosis of mental disorders is not an exact science, and minor diagnostic nuances that have little clinical importance can have major financial consequences. For physical illnesses, DRG creep is easily detected at the technical level; the results of laboratory tests, surgical procedures, and physical examinations can be used to verify coding. However, mental health records consist of self-reported data that are then translated into subjective DSM categories, which makes intentional upcoding difficult to detect.

Conclusions

The definition of mental illness used by states is not simply a question of semantics or terminology. The specific statutory language adopted by state legislatures determines which patients are reimbursed for medical care. Unfortunately, the new "pick and choose" approach that most states are using to define mental illness has little, if any, clinical basis. Legislating diagnostic criteria for impairment on the basis of political and economic factors may limit treatment efforts and ultimately fail those most in need of care.

How should state legislatures develop a definition of mental illness for parity laws? First, policy makers must understand how full service use, treatment, and costs vary under the different definitions of mental illness that are currently in use. The variation in parity statutes allows researchers to make objective comparisons of the prevalence rates of covered mental illnesses under each definition. Research is needed to measure the extent to which the different definitions include or exclude certain mentally ill populations. Research on how a person's insurance status is related to the availability and effectiveness of services is also critical. Such studies are also crucial in determining the effects of limited parity bills. To prevent potential upcoding, insurers must design reimbursement rates that are clinically meaningful.

Mental health parity laws have accomplished a great deal by recognizing the inequalities in coverage between mental and physical illness and by focusing much-needed attention on mentally ill populations. We can improve access to care only when we determine which of the definitions of mental illness used in parity laws increase access to care and only when we understand how implementation of parity is affected by bills that use broad-based rather than narrow definitions of mental illness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant MH-18828-11 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the Center for Mental Health Services Research at the University of California, Berkeley. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Daniel Gitterman, Ph.D., and Darcy Gruttadaro, J.D.

Dr. Peck is a resident in internal medicine at Stanford University Hospitals in Stanford, California. When this work was done, she was a research associate in the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, where Dr. Scheffler is professor of health economics and public policy. Dr. Scheffler is also affiliated with the Center for Mental Health Services Research at the University of California, Berkeley. Send correspondence to Dr. Peck at the Department of Medicine, Stanford University, 300 Pasteur Drive, S101 (m/c 5109), Stanford, California 94305 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. States that use "broad-based" definitions of mental illness in state parity statutes

|

Table 2. States that use "serious mental illness" definitions in state parity statutes

|

Table 3. States that use "biologically based mental illness" definitions in state parity statutes

1. Scheffler R, Gitterman D, Peck M: The political economy of mental health insurance in the United States, in Insurance Parity for Mental Health: Cost, Access, and Quality: Final Report to Congress by the National Advisory Mental Health Council. Edited by Kirschstein R. NIH pub 00-4787. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2000Google Scholar

2. Buck J, Teich J, Umland B, et al: Behavioral health benefits in employer-sponsored health plans. Health Affairs 18(2):67-78, 1997Google Scholar

3. Varmus H: Parity in Coverage of Mental Health Services in an Era of Managed Care: An Interim Report to Congress by the National Advisory Mental Health Council. NIH pub 98-4322. Bethesda, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, 1998Google Scholar

4. Levinson C, Druss B: The evolution of mental health parity in American politics. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:139-146, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cooper J: On the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fourth Edition. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:4-8, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Heyada R: Understanding Biological Psychiatry. New York, Norton, 1996Google Scholar

7. McLaren N: Is mental disease just brain disease? The limits to biological psychiatry. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 26:270-276, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Schinnar A, Rothbard A, Kanter R, et al: An empirical literature review of definitions of severe and persistent mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:1602-1608, 1990Link, Google Scholar

9. Task Force Report: Toward a National Definition of Severe and Persistent Mental Illness. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1991Google Scholar

10. Health Care Reform for Americans With Severe Mental Illnesses: Report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1447-1465, 1993Link, Google Scholar

11. National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Priority and Special Populations. Available at www.nami.orgGoogle Scholar

12. McElhaney S, Barton J: Advocacy and services: the National Mental Health Association and prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention 15:313-322, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. American Psychiatric Association Practice Research Network: The Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHPB) Parity Study. Available at www.psych.orgGoogle Scholar

14. Custer W: Health Insurance Coverage and the Uninsured. Health Insurance Association of America. Available at www.hiaa.orgGoogle Scholar

15. Narrow W, Regier D, Goodman S, et al: A comparison of federal definitions of severe mental illness among children and adolescents in four communities. Psychiatric Services 49:1601-1608, 1998Link, Google Scholar

16. Kendler K, Gardner C: Boundaries of major depression: an evaluation of DSM-IV criteria. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:172-177, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Regier D, Knelber C, Rae D, et al: Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments in mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:109-115, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Judd L, Paulus M, Wells K, et al: Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1411-1417, 1996Link, Google Scholar

19. Cohen C: Overcoming social amnesia: the role for a social perspective in psychiatric research and practice. Psychiatric Services 51:72-78, 2000Link, Google Scholar

20. Wells K, Burnam A, Rogers W, et al: The course of depression in adult outpatients: results from the medical outcomes study. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:788-794, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Knitzer J: Unclaimed Children: The Failure of Public Responsibility to Children and Adolescents in Need of Mental Health Services. Washington, DC, Children's Defense Fund, 1982Google Scholar

22. Report of the Surgeon General's Conference on Children's Mental Health: A National Action Agenda. Washington, DC, US Public Health Service, 2000Google Scholar

23. Ell K, Aisenberg E: Stress-related disorders, in Advances in Mental Health Research: Implications for Practice. Washington, DC, National Association of Social Workers Press, 1998Google Scholar

24. National Mental Health Association: General Mental Health. Available at www.nmha.orgGoogle Scholar

25. Johnson J, Weissman M, Klerman G: Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 267:1478-1483, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Broadhead E, Blazer D, George L, et al: Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 264:2524-2528, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Olfson M, Broadhead E, Weissman M, et al: Subthreshold psychiatric symptoms in a primary care group practice. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:880-886, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hsia D, Krushat M, Fagan A, et al: Accuracy of diagnostic coding for Medicare patients under the prospective-payment system. New England Journal of Medicine 318:352-355, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar