Quality of Life in Social Anxiety Disorder Compared With Panic Disorder and the General Population

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Quality of life in a treatment-seeking cohort of patients with social anxiety disorder was compared with that of patients with panic disorder who were matched for age, comorbid illnesses, and gender and with population-based norms. METHODS: The study participants were 33 patients with social anxiety disorder and 33 patients with panic disorder who had participated in clinical trials and who had completed the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form-36 (SF-36) as part of a baseline evaluation. The patients did not have significant comorbid psychiatric disorders. Paired t tests were used to compare baseline scores on subscales of the SF-36 between the two cohorts. One-sample t tests were used to compare scores on subscales of the SF-36 with expectation scores based on 2,474 persons from the general population. RESULTS: Compared with the general population, the patients with social anxiety disorder had significantly greater impairment as measured by the SF-36 social functioning and mental health subscales. Subscale scores also indicated poorer emotional role functioning, but the difference was not significant. However, they were significantly less impaired than the patients with panic disorder in terms of physical functioning, physical role, and mental health. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with social anxiety disorder who do not have significant comorbid depression or anxiety are substantially impaired in quality of life, but to a lesser extent than patients with panic disorder, who suffer from both mental and physical impairments in quality of life.

Studies of quality of life among patients with social anxiety disorder have been conducted with epidemiologic (1,2,3) and clinical samples (4,5) and have used a variety of measures of disability. In a study by Schneier and colleagues (4), 32 patients with social anxiety disorder showed greater impairment than 14 healthy control subjects on scales specific to social anxiety—the Disability Profile and the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale. Two reports of data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study also demonstrated impairment in educational status, financial and employment stability, marital status, and social support among persons with social anxiety disorder (3,6). Although some impairment may have been due partly to comorbid disorders, even patients with subthreshold social anxiety disorder showed impairment.

Moreover, in a community sample of persons with social anxiety disorder, Stein and Kean (2) found that comorbid depression contributed only moderately to the dysfunction in daily activities, interpersonal relationships, performance in school, educational attainment, dissatisfaction with a variety of life domains, and poor quality of life associated with social anxiety disorder as measured by the Quality of Well-Being Scale. Three studies have shown that effective treatment improves the quality of life of patients with social anxiety disorder (5,7,8).

Although the utility of quality-of-life scales that are specific to social phobia has been demonstrated (4), such scales do not allow the broader perspective provided by directly comparing the relative severity of dysfunction across different disorders. Such comparisons may be better accomplished with more widely used general measures, such as the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form-36 (SF-36) (9). Wittchen and colleagues (1) found significant impairment on all measures of mental health and on the general health subscale of the SF-36 in a nonclinical population of persons with social anxiety disorder. Their study excluded treatment-seeking patients. As expected, patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders reported even more impairment.

Rather than simply comparing SF-36 scores of persons with social anxiety disorder and healthy controls, we selected an additional cohort as a benchmark for level of disability. The disability and impairment in quality of life associated with panic disorder have been well documented (10,11,12,13,14,15). Patients with panic disorder, although often misdiagnosed and undertreated, frequently seek medical care (16,17,18).

To our knowledge, only one study has directly compared the impact of social anxiety disorder and panic disorder on quality of life (19). That study showed that patients with social anxiety disorder had greater "life disruptions" than those with panic disorder, but it did not use a validated quality-of-life scale. Schonfeld and colleagues (20) reported SF-36 scores for patients with previously undetected depression or anxiety disorders diagnosed through a primary care screening procedure. Patients with social anxiety disorder and patients with both panic disorder and agoraphobia were included. Although statistical tests were not used for the comparisons, the patients with panic disorder had more consistent impairment than those with social anxiety disorder.

In the study reported here we further examined the relative effects of social anxiety disorder and panic disorder on quality of life. Quality of life as assessed by the SF-36 was compared between treatment-seeking patients with social anxiety disorder and an age- and sex-matched control group with panic disorder. The scores of the patients with social anxiety disorder were also compared with population-based expectation scores.

Methods

Study subjects

The sample comprised 66 patients with social anxiety disorder or panic disorder who had participated in clinical trials in the Anxiety Disorders Program at Massachusetts General Hospital between 1993 and 2000. The patients with social anxiety disorder were 33 consecutive patients (12 men and 21 women) who presented for one of three clinical psychopharmacology trials for social anxiety disorder. Thirty-three patients with panic disorder (the control group) were matched for age (within three years) and gender. Because the social anxiety cohort included no patients with comorbid major depression or panic disorder, we excluded patients with current major depression or social anxiety disorder from the panic disorder cohort.

Editor's Note: This paper is part of an occasional series on anxiety disorders edited by Kimberly A. Yonkers, M.D. Contributions are invited that address panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Papers should focus on integrating new information that is clinically relevant and that has the potential to improve some aspect of diagnosis or treatment. For more information, please contact Dr. Yonkers at 142 Temple Street, Suite 301, New Haven, Connecticut 06510; 203-764-6621; [email protected].

The patients were recruited through advertisements or clinical referrals. They met criteria for the generalized type of social anxiety disorder or panic disorder with or without agoraphobia as diagnosed by physicians and other doctoral-level clinicians with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (21). For patients in both groups, the primary disorder was sufficiently severe to warrant entry into a clinical treatment trial, such as a score of at least 50 on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) (22) for patients with social anxiety disorder and at least 4 on the Clinical Global Impression severity scale (CGI-S) (23) for those with panic disorder. Possible scores on the LSAS range from 0 to 144, with higher scores indicating more severe social phobia. Possible scores on the CGI-S range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater severity of illness. Patients with unstable comorbid medical disorders or substance use disorders were excluded.

Measures

The SF-36 consists of eight subscales that assess both physical and emotional quality of life. These include vitality (a measure of energy level and fatigue), social functioning, emotional role (difficulties in work or daily activities due to emotional problems), mental health (anxiety and depression), physical functioning, physical role (difficulties in work or daily activities due to physical problems), body pain, and general health. For each subscale, scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. The validity and reliability of the SF-36 have been well established in large samples drawn from the general population and in samples of patients with medical and psychiatric disorders (24,25,26). Population-based norms and further scale descriptions are available (27).

As part of the baseline evaluation, the patients with social anxiety disorder completed the SF-36 and other measures, including the LSAS, the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (28), and the CGI-S. The clinical trials were approved by the institutional review board, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Data analysis

One-sample t tests were used to compare scores on SF-36 subscales with age- and gender-specific expectation scores based on 2,474 persons from the general population (27). Paired t tests were used to compare baseline scores for the matched cohorts of patients with social anxiety disorder and patients with panic disorder.

Results

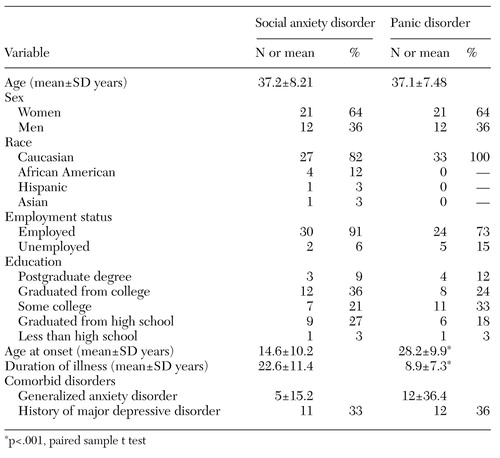

Basic demographic information and morbidity ratings for the two cohorts are summarized in Table 1. In general, the two cohorts were comparable. The social anxiety group had an earlier age at onset (t=5.39, df=32, p<.001), which is consistent with the natural course of the disorder relative to that of panic disorder (29). Given that the cohorts were matched for age, the earlier age at onset of social anxiety disorder translates into a significantly longer duration of illness (t=5.58, df=32, p<.001).

In addition, the patients with social anxiety disorder had lower rates of comorbid generalized anxiety disorder, which may reflect the different entry criteria used in the studies from which the cohorts were drawn. Patients with other current comorbid disorders were excluded from the sample of patients with social anxiety disorder, and none of the patients with a history of depression had depression at the time of the study.

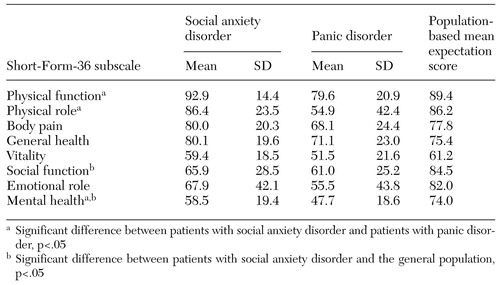

Mean±SD scores on the SF-36 subscales for the two groups are listed in Table 2, along with population-based means. Compared with the age- and gender-matched general population scores, the patients with social anxiety disorder showed significantly greater impairment in social functioning (t=-3.601, df=32, p<.001) and mental health (t=-4.589, df=32, p<.001); greater impairment in emotional role functioning was also noted, but the difference was not statistically significant. No differences in the four aspects of physical functioning or in vitality were observed between the patients with social anxiety disorder and the general population.

No significant differences were observed between the patients with panic disorder and the patients with social anxiety disorder on SF-36 measures of social functioning or emotional role functioning. However, the patients with panic disorder were significantly more impaired in physical functioning (t=2.88, df=32, p<.01), physical role (t=3.59, df=32, p<.01), and mental health (t=2.6, df=32, p<.05). The patients with panic disorder showed greater impairment on three other scales, but the differences were not significant. The effect sizes were small to medium (d=.35 for body pain, d=.3 for general health, and d=.29 for vitality) (30). The severity of illness in both groups was in the moderate to marked range as measured by mean±SD scores on the CGI-S (5.1±.65 for social anxiety disorder and 4.72±.73 for panic disorder). Consistent with the findings of Wittchen and colleagues (1), age at onset and duration of illness were not correlated with scores on any SF-36 subscale.

Discussion

Treatment-seeking patients with social anxiety disorder were significantly more impaired in mental health and social functioning than the general population. They also showed greater impairment in functioning at work and in other daily activities as a result of emotional problems, but the differences were not significant. This level of impairment could not be attributed to the presence of comorbid disorders. However, the patients with social anxiety disorder did not demonstrate impairment on measures of physical functioning or vitality, a measure of energy level and fatigue. In contrast, the patients with panic disorder showed impairment on both physical and psychological measures, which is consistent with the greater somatic focus and physical distress seen in clinical samples of these patients.

The patients with panic disorder showed greater impairment in mental health and vitality than those with social anxiety disorder. No significant difference was observed in social or role functioning. Our findings are in direct contrast with those of Norton and colleagues (19), who found greater disruption in life circumstances such as employment among patients with social anxiety disorder than among patients with panic disorder.

The results of our study suggest that, at least for patients who do not have comorbid major depression and anxiety, panic disorder may have a greater impact on quality of life than social anxiety disorder. Whereas the somatic symptoms of panic disorder are often prominent and may drive patients to seek treatment, the lack of significant physical impairment among patients with social anxiety disorder and the avoidant nature of these individuals may result in a generally lower degree of help-seeking behavior, especially among those who are the most severely ill.

In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, only 19.6 percent of persons with social anxiety disorder sought treatment (29). In the National Comorbidity Study (31), only 4 percent of persons with social anxiety disorder without comorbid illnesses sought treatment. Among patients who reported significant role impairment, only 28 percent of those with social anxiety disorder sought treatment.

In a study of 9,000 patients who were receiving health care through a health maintenance organization, the prevalence of social anxiety disorder was 8.2 percent (32). Consistent with the epidemiologic reports cited above, only .5 percent of the affected patients had received a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder from their physician in the previous year, and fewer than a third of those who were diagnosed were receiving treatment. The low rates of treatment seeking among persons with social anxiety disorder contrast with data that suggest that 70.5 percent of persons with agoraphobia who have self-reported role impairment seek treatment (31).

Furthermore, highly impaired persons with social anxiety disorder may be particularly underrepresented in clinical and research samples because they avoid the social interaction inherent in seeking treatment. Olfson and colleagues (33) reported that the greatest barriers to treatment for patients with social anxiety disorder were access problems and fear of what others might think or say.

In further support of this hypothesis, Erwin and colleagues (34) reported that the mean severity of illness of patients with social anxiety disorder who used a Web-based treatment information service was one standard deviation greater than that of patients who visited a clinician's office. Further efforts to increase public awareness of the availability of effective treatments for social anxiety disorder and decrease perceived barriers to treatment seeking among persons who are the most severely affected are warranted.

In addition, in the subset of our social anxiety cohort for whom data were available, the mean age at onset was 14.6 years, compared with 28.2 years for patients with panic disorder. The mean duration of illness was 22.6 years for the patients with social anxiety disorder, compared with 8.9 years for the patients with panic disorder. As Schneier and colleagues (4) have proposed, social anxiety disorder is a chronic illness with an early onset, and persons who have this disorder may not be able to provide meaningful answers to questions that involve comparing current functioning with an earlier period of normal functioning. Thus Schneier and colleagues suggested that quality of life among these persons may be better assessed with measures specific to social anxiety disorder.

However, even with a more specific scale, the fact that symptoms of social anxiety disorder develop at an early age may contribute to lower expectations about "normalcy" and thus to lower levels of distress and impairment as assessed by any measure that relies on self-reports. The associated failure to recognize that social anxiety symptoms and related impairment represent a disorder that might be improved with treatment may also contribute to the frequent scenario in which patients with social anxiety disorder present for treatment after enduring ten to 20 years of symptoms.

Furthermore, the early onset of social anxiety disorder makes it difficult to project the life course a person might have followed had he or she not become symptomatic. Thus it is difficult to measure the loss of potential productivity or career advancement due to symptoms of social anxiety disorder, although this scenario is reported clinically by some patients. The higher rate of overall employment among those with social anxiety disorder in this study than among the patients with panic disorder may reflect the different effects of each disorder on a person's career path. Patients who develop panic disorder may experience disrupted employment, whereas lifelong social anxiety disorder may be more likely to alter a person's career path. This difference may partly explain the lower impairment among patients with social anxiety disorder than among those with panic disorder.

As with many clinical trials, our protocols mandated the exclusion of subjects with certain comorbid conditions, which produced a social anxiety disorder cohort without significant comorbid illness. In contrast, previous studies of clinical and epidemiologic samples documented high rates of comorbid disorders among patients with social anxiety disorder (31,35). Thus our sample probably represents a select and potentially less symptomatic group, which may partly explain why the levels of dysfunction were only moderate. Davidson and colleagues (3) showed that much of the impairment associated with social anxiety disorder is attributable to comorbid disorders. They proposed that social anxiety disorder without comorbid depression or anxiety may be a milder form of the disorder.

Wittchen and colleagues' study (1) of a nonclinical sample of patients with social anxiety disorder who were assessed by the SF-36 also demonstrated significantly more impairment among patients with comorbid disorders than among those with "pure" social anxiety disorder. Furthermore, SF-36 scores for this pure sample were similar to those for our sample of patients who had social anxiety disorder without significant current mood or anxiety disorders.

In addition, one hypothesis is that social anxiety disorder, given its early onset, increases the risk that comorbid disorders will develop subsequently. Thus social anxiety disorder may have its greatest adverse impact on function and quality of life through its association with the development of comorbid pathology. The development of complications due to comorbid disorders among patients with social anxiety disorder may thus be preventable if social anxiety disorder is detected and treated early.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that patients with social anxiety disorder who do not have comorbid depression or anxiety disorders are significantly impaired in mental health and social functioning, but to a lesser extent than patients with panic disorder, who have both mental and physical impairments in quality of life. Patients who have social anxiety disorder without comorbid depression or anxiety and who seek treatment may represent patients with lower levels of dysfunction, perhaps partly because more symptomatic patients experience more direct interference with treatment seeking as a result of the symptoms themselves. Nonetheless, the early onset of social anxiety disorder, its associated distress and impairment, and complications related to high rates of comorbid disorders underscore the importance of early detection and treatment to reduce the adverse impact of this disorder on quality of life and functioning.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported in part by grant K23-MH-01831-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Simon.

The authors are affiliated with the Anxiety Disorders Program at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 15 Parkman Street, WAC 815, Boston, Massachusetts 02114 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 33 patients with social anxiety disorder and 33 patients with panic disorder who completed measures of quality of life

|

Table 2. Quality of life ratings among 33 patients with social anxiety disorder and 33 patients with panic disorder compared with the general population

1. Wittchen H, Fuetsch M, Sonntag H, et al: Disability and quality of life in pure and comorbid social phobia: findings from a controlled study. European Psychiatry 15:46-58, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Stein M, Kean Y: Disability and quality of life in social phobia: epidemiologic findings. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1606-1613, 2000Link, Google Scholar

3. Davidson R, Hughes D, George L, et al: The epidemiology of social phobia: findings from the Duke Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Psychological Medicine 23:709-718, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Schneier F, Heckelman L, Garfinkel R, et al: Functional impairment in social phobia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:322-331, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

5. Stein M, Fyer A, Davidson J, et al: Fluvoxamine treatment of social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a double blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:756-760, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Davidson R, Hughes D, George L, et al: The boundary of social phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:975-983, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Safren S, Heimberg R, Brown E, et al: Quality of life in social phobia. Depression and Anxiety 4:126-133, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

8. McCollum S, Kavoussi R, Pande A: Gabapentin Treatment of Social Phobia: Improvement in Quality of Life. Presented at the annual meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, held May 30 to June 2, 2000, in Boca Raton, FlaGoogle Scholar

9. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473-483, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Candilis P, McLean R, Otto M, et al: Quality of life in patients with panic disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:429-434, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Judd LL: Functioning and well-being of patients with panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:213-218, 1996Link, Google Scholar

12. Massion A, Warshaw M, Keller M: Quality of life and psychiatric morbidity in panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:600-607, 1993Link, Google Scholar

13. Hollifield M, Katon W, Skipper B, et al: Panic disorder and quality of life: variables predictive of functional impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:766-772, 1997Link, Google Scholar

14. Markowitz J, Weissman M, Ouellette R, et al: Quality of life in panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:984-992, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rubin H, Rapaport M, Levine B, et al: Quality of well being in panic disorder: the assessment of psychiatric and general disability. Journal of Affective Disorders 57:217-221, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Roy-Byrne P, Stein M, Russo J, et al: Panic disorder in the primary care setting: comorbidity, disability, service utilization, and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:492-499, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Katerndahl D, Realini J: Use of health care services by persons with panic symptoms. Psychiatric Services 48:1027-1032, 1997Link, Google Scholar

18. Buller R, Winter P, Amering M, et al: Center differences and cross-national invariance in help-seeking for panic disorder. A report from the Cross-National Collaborative Panic Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:135-141, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

19. Norton G, McLeod L, Guertin J, et al: Panic disorder or social phobia: which is worse? Behavior Research Therapy 34:273-276, 1996Google Scholar

20. Schonfeld W, Verboncoeur C, Fifer S, et al: The functioning and well-being of patients with unrecognized anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 43:105-119, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. First M, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1995Google Scholar

22. Liebowitz M: Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry 22:141-173, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Health, 1976Google Scholar

24. Hays R, Wells K, Sherbourne C, et al: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:11-19, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Stewart A, Greenfield S, Hays R, et al: Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. JAMA 262:907-913, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Wells K, Stewart A, Hays R, et al: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. JAMA 262:914-919, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, et al: SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Lincoln, RI, Quality Metric Incorporated, 2000Google Scholar

28. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 23:56-61, 1960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Schneier F, Johnson J, Hornig C, et al: Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:282-288, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

31. Magee W: Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:159-168, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Katzelnick D: The direct and indirect costs of social anxiety disorder in managed care patients. Presented at the Societal Impact of Anxiety Disorders Symposium, held May 16, 1999, in Washington, DCGoogle Scholar

33. Olfson A, Guardino M, Struening E, et al: Barriers to the treatment of social anxiety. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:521-527, 2000Link, Google Scholar

34. Erwin BA, Turk CL, Fresco DM, et al: The internet: the avoidance superhighway for persons with social anxiety? Presented at the annual convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, held 16 to 19, 2000, in New OrleansGoogle Scholar

35. Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Wilson C: Buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in social phobia. Journal of Affective Disorders 39:115-121, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar