Best Practices: Detection of Intimate-Partner Violence Among Members of a Managed Behavioral Health Organization

Abstract

Introduction by the column editor: This column describes a creative effort on the part of a national behavioral managed care plan to identify cases of domestic violence in its covered population. Although the screening efforts by intake counselors and clinicians yielded a lower rate of domestic violence than would have been expected, the effort established a baseline or benchmark from which the organization can now work. Clinical benchmarks are critical to developing an understanding of best practices. In this case, the benchmark finding initiated a best practices process through which this organization—and, hopefully, others—will continue to create better methods for identifying and helping people who experience domestic violence.

Conservative estimates of the number of women who are victims of intimate-partner violence, more commonly referred to as domestic violence, range from 1.5 to 4 million a year (1,2). Although estimates vary widely, the annual prevalence may be as high as 30 percent (3), depending on the definition of domestic violence used and on the study site or the source of the statistics. Surveys of patients in community clinics and emergency departments tend to show a much higher prevalence than general population surveys (4).

These differences notwithstanding, it is likely that all sources underestimate the actual number of victims, because domestic violence is underreported by its victims and underdiagnosed by health practitioners, who can be uncomfortable asking about violence, unfamiliar with available community resources, or fearful of retribution (5,6). Thompson and colleagues (5) estimated that as few as 3 percent of cases are identified.

The mental and physical health consequences of domestic violence are severe (7). The triad of high risk in mental health comprises vulnerability to suicide, homicide, and domestic violence. Recognizing this risk, professional organizations in the health care industry have issued calls to establish domestic violence screening protocols in all health care settings (8). Nevertheless, relatively few general or behavioral managed health care companies have instituted guidelines to encourage and facilitate this practice (9), despite evidence that training and screening protocols can substantially increase the number of cases that are identified (9) and that victims of domestic violence cost health plans significantly more in terms of both behavioral health care and ambulatory care for other health problems (10,11).

Existing protocols are tailored to providers of primary care and emergency services. Our review of the literature found no published domestic violence screening protocols for behavioral health care providers, who are typically confronted with far more subtle indicators than the obvious physical injuries encountered by emergency or primary care providers. Domestic violence is often obscured by substance abuse, anxiety, or mood disorders.

In pursuit of best practices in detecting domestic violence, there is a clear need for a refined screening protocol designed specifically for behavioral health care providers. To evaluate the existing protocol used by our intake counselors, we compared the rate of detection of domestic violence by these counselors with the rate among our network clinicians, who have no screening guidelines. We expected that these data could be used to establish a benchmark for detecting domestic violence among members of our managed behavioral health organization.

Methods

United Behavioral Health (UBH), a national managed behavioral health organization that serves 22 million people, has been screening for and documenting the incidence of domestic violence since the mid-1990s. In UBH's employer division, telephone intake counselors—master's-level mental health professionals who respond to members' initial requests for services and referrals—are trained to routinely inquire about domestic violence during initial telephone assessments.

Intake procedure

During the initial telephone assessment, the intake counselor confirms the member's eligibility, assesses the nature and urgency of the problem so that the member can be directed to an appropriate network clinician, and authorizes an initial ten outpatient sessions. The counselor also carefully screens for domestic violence. To put the member at ease, the intake counselor says, "We have a series of safety questions we ask everyone."

The protocol for the assessment is as follows. After screening for suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, and substance abuse, the counselor asks, "Is there violence in the home?" If the member's response is affirmative, the counselor then establishes the caller's role in and the frequency and severity of fights. Next the caller is asked, "Are there children or elders at home?" and "Are they victims of abuse?" Special reporting and documentation requirements are followed throughout the assessment.

If the caller is identified as a victim, the person is asked whether he or she has a safety plan and, if not, whether he or she needs assistance or resources to make such a plan. If the caller is determined to be the perpetrator, he or she is asked to make a contract for safety—a verbal agreement not to inflict harm or engage in other forms of abuse. The counselor then makes an emergency appointment with a clinician and flags domestic violence as an issue to be addressed by the clinician. Later, the care manager follows up with the clinician on the client's treatment plan. For cases in which the caller was identified as the perpetrator, the care manager verifies that he or she kept the appointment.

Although there is currently no comparable screening requirement for network clinicians, UBH expects that clinicians will assess for domestic violence as part of usual care. The form submitted by clinicians to request additional outpatient treatment sessions specifically asks about the presence of abuse and the member's role in it. Likewise, when a patient is hospitalized or is receiving treatment at a network facility, the UBH care manager uses the same screening questions.

Data collection

The database for this analysis consisted of intake assessments, outpatient treatment request forms, and facility reviews in UBH's employer division from January 1 through September 30, 2000. To enable domestic violence to be isolated, data for victims and perpetrators of child and elder abuse were excluded. When these criteria were used, 122,446 reviews for 83,964 members were identified. A member may have had multiple reviews in our database if he or she called for a clinical referral more than once during the study period or required more than ten sessions of treatment. Thus it is possible that both an intake counselor and a network clinician separately detected a single case of domestic violence.

Results

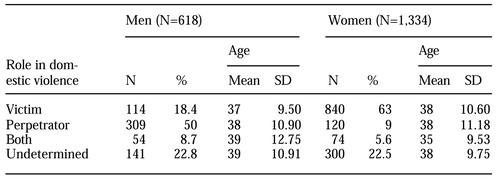

Intake counselors and network clinicians identified 1,952 individual members who were involved in an abusive relationship, either as a victim or as a perpetrator, representing 2.3 percent of the total sample of members who were receiving treatment. The sex and average age of these individuals and their roles in the domestic violence are listed in Table 1.

The clinicians were more likely than the intake counselors to have identified a case of domestic violence. A total of 1,338 cases (68.5 percent) were identified by clinicians, compared with 370 cases (18.9 percent) by intake counselors (χ2=439.01, df=2, p<.001). A total of 244 cases (12.5 percent) were identified by both an intake counselor and a clinician.

We were concerned that records in which abuse was not indicated may have included cases for which the intake counselor did not specifically ask about abuse. To investigate the likelihood of an intake counselor's documenting "no abuse" by default, we looked at the entire sample of 122,446 reviews. Among the intake counselors' initial telephone assessments, 97.3 percent had "unknown" in the abuse field, 1.8 percent had "no," and .9 percent had "yes." Although it seems to be relatively rare for an intake counselor to have entered "no abuse" by default, the high proportion of "unknown" entries is cause for concern about the effectiveness of the screening protocol.

Of the 370 patients who were determined by an intake counselor to have been involved in an abusive relationship, 36 were advised to file a police report, and another 35 were referred to a shelter for victims of battering. Information about the frequency or nature of the recommendations and referrals made by the network clinicians was not available.

Discussion

Because domestic violence is more prevalent than suicidality and homicidality and receives less attention, assessing patients for domestic violence is just as important as assessing them for these other two risk factors. Detection of domestic violence and treatment of victims and perpetrators is an integral part of high-quality behavioral health care. Domestic violence is underreported in all settings. Our analysis provided a benchmark for detecting domestic violence in an organized managed behavioral health delivery system. It revealed that domestic violence is more likely to be identified by clinicians during the course of treatment than by intake counselors during an initial telephone assessment.

The difference in detection rates between the two groups of professionals was statistically significant and was not surprising. Intake counselors have a limited amount of time in which to make an assessment about a member's situation, and the member may not be forthcoming even if asked a direct question. Clinicians have considerably more time to make an assessment and have a greater opportunity to develop a therapeutic alliance in which the patient can disclose information about abuse.

Our data had some limitations. First, even general population estimates of domestic violence—which indicate comparatively low rates—may not accurately reflect the demographic composition of a managed care population of employed individuals, which tends to be slightly older and more highly educated than the general population. Nevertheless, even though Thompson and colleagues (5) estimated that rates of detection of domestic violence are universally low, the rate that we found is distressingly low. On the other hand, to our knowledge it is the first published estimate of domestic violence in a managed behavioral health care population.

Second, our sample involved selection bias. The sample included only persons who sought help or who had attended more than ten sessions of treatment. It did not include members who had experienced domestic violence that was undetected by an intake counselor and who did not follow through on the referral to a provider or members who had attended fewer than ten sessions, for whom clinicians would not have submitted an outpatient treatment request form. In addition, among members who attended more than ten sessions, the prevalence of domestic violence reported by clinicians may have been lower than the actual prevalence because of clinicians' concerns about confidentiality. Members may have had similar concerns, which would have resulted in an even lower detection rate. The 2.3 percent detection rate is a worst-case estimate for the UBH system.

Despite the study's limitations, the findings can be used to develop domestic violence guidelines and protocols that are more appropriate for organized systems of behavioral health care, thus advancing our pursuit of best practices in detection and treatment. Currently there are no protocols for behavioral health providers that are comparable to guidelines published for physical health care providers. UBH has designed a domestic violence prevention program, in collaboration with the Family Violence Prevention Fund and Physicians for a Violence-Free Society, that will equip intake staff to more effectively screen for domestic violence, assess a member's risk level, and help develop an appropriate treatment plan. A comparable program has been designed for network clinicians.

The program highlights the need for behavioral health providers to recognize more subtle indicators of domestic violence than the obvious physical injuries that are more often encountered by primary care providers—that is, domestic violence is often obscured by substance abuse or presents as an anxiety or mood disorder. Once the program has been implemented, UBH will evaluate its effectiveness by comparing identification of domestic violence with the baseline rates reported here. Given the close association between economic conditions and the prevalence of domestic violence, recent warnings of a downturn in the nation's economy increase the urgency of our efforts to better detect and treat domestic violence.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Tina Ruiz, Ph.D.

The authors are affiliated with United Behavioral Health, 425 Market Street, 27th Floor, San Francisco, California 94105 (e-mail, [email protected]). William M. Glazer, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Roles and average ages of 1,952 clients of a managed behavioral health organization who were identified as having been involved in domestic violence

1. Tjaden P, Thoennes N: Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998Google Scholar

2. American Medical Association: AMA diagnostic and treatment guidelines on domestic violence. Archives of Family Medicine 1:39-47, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al: Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA 277:1400-1401, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Tollestrup K, Sklar D, Frost FJ, et al: Health indicators and intimate partner violence among women who are members of a managed care organization. Preventive Medicine 29:431-440, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Thompson RS, Meyer BA, Smith-DiJulio K, et al: A training program to improve domestic violence identification and management in primary care: preliminary results. Violence Victims 13:395-410, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Goldberg WG, Tomlanovich MC: Domestic violence in the emergency department. JAMA 251:3259-3264, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al: The "battering syndrome": prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic partner violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Annals of Internal Medicine 123:737-746, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. American Medical Association: Violence against women: relevance for medical practitioners. JAMA 267:3184-3189, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Family Violence Prevention Fund: Most managed care companies fail to require routine screening for domestic violence. Press release, Feb 16, 2000Google Scholar

10. Thompson RS, Rivara FP, Thompson DC, et al: Identification and management of domestic violence: a randomized trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 19:253-263, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wisner CL, Gilmer TP, Saltzman LE, et al: Intimate partner violence against women: do victims cost health plans more? Journal of Family Practice 48:439-443, 1999Google Scholar