Factors Associated With Receipt of Behavioral Health Services Among Persons With Substance Dependence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to identify demographic and clinical variables that predict use of behavioral health services among persons with substance dependence. METHODS: Interviews were conducted with 1,893 adults who endorsed items on the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse in 1995 and 1996 that were consistent with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of dependence on at least one substance, excluding cigarettes. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify significant predictor variables. RESULTS: Among persons with substance dependence, only 18.3 percent had sought substance abuse or mental health treatment, or both, in the previous year. Female sex, high family income, a history of being arrested or booked, concurrent psychiatric comorbidity, self-perception of having a drug or alcohol problem, and the number of substances involved all predicted treatment use. One-third of substance-dependent individuals who used services reported receiving mental health care that did not include any substance use component. Persons with higher education levels were more likely to use mental health care only. In contrast, persons who used public insurance or were uninsured, had been booked or arrested, or perceived themselves as having a drug or alcohol problem were less likely to obtain mental health care only. CONCLUSIONS: Several clinical and demographic variables were predictive of some type of treatment use by substance-dependent individuals. Persons who used mental health care only were more likely to be female, to be of higher socioeconomic status, not to have a history of involvement with the legal system, and to have problems with alcohol or marijuana but not to perceive themselves as needing addiction treatment.

Substance addiction is a significant health problem. It resulted in 132,000 deaths in 1992 alone and cost American society $276 billion a year in 1995 (1). Despite the highly negative effects of substance dependence and the availability of relatively effective interventions for it (2), few persons with substance use disorders actually seek treatment (3). Identifying demographic and clinical variables that predict use of treatment can assist providers in understanding and ultimately eliminating barriers to care (4).

Among people with substance problems, certain demographic variables have been associated with seeking some type of treatment—namely, female sex (3,5,6), older age (3,7), unemployment (3,7), poverty (7), and having been arrested (6). The picture is more mixed with regard to ethnicity and marital status (5,6,7,8). With respect to clinical variables, having a comorbid psychiatric illness substantially increases the likelihood of obtaining services (5,9,10).

Research has documented the benefits of receiving a treatment that is specifically designed to address the unique needs of the individual who has substance dependence, whether in isolation or as part of a dual diagnosis (11,12,13,14). Yet a notable proportion of individuals with substance dependence who obtain mental health treatment do not seek services that are designed to address their addiction. Among individuals who have a substance dependence disorder without a co-occurring psychiatric illness, 4.7 to 14.2 percent are seen in the mental health system rather than in settings designed specifically to address substance use disorders (10,15).

The National Comorbidity Survey found that persons who had alcohol or drug dependence without a co-occurring mental illness were as likely or more likely to be seen in mental health service settings than in specialty substance treatment (10). A study of national expenditures made in 1996 for mental health and substance abuse treatment found that $1,638,000 (13 percent) of the money spent to treat people with a primary substance abuse diagnosis went to psychiatric hospitals, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals (16). Persons with dual diagnoses have been similarly found to obtain mental health services two or three times as often as specialty substance care (10,15,17).

This study used a nationally representative sample to examine the role of a variety of demographic and clinical variables in predicting treatment use among individuals whose self-reports indicate that they currently meet the criteria for substance dependence. Both factors that are predictive of treatment use in general and those that identify which subpopulations are most likely to obtain mental health services, in contrast with specialty substance care, were explored.

Methods

The National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) (18) is a nationwide household survey designed to elucidate national trends in the use of a wide variety of legal and illicit substances as well as to query about related topics, such as treatment. It uses a multistage sample design to accurately represent the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States 12 years of age and older. In the 1995 survey, 17,747 individuals were interviewed about their substance use, which constituted a response rate of 80.6 percent. The 1996 survey included 18,269 participants and had a response rate of 78.6 percent. For this study, the results from the two surveys were combined, and only respondents aged 18 years and older were included; the total sample comprised 26,883 persons.

Trained nonprofessional interviewers privately administered the hour-long NHSDA instrument. Although portions of the instrument followed an oral interview format, the primary sections used in this study were administered as questionnaires that the participants read, unless the participant's reading level or personal preference dictated otherwise. To ensure the privacy of participants' responses, respondents completed their own answer sheets, which were placed, unreviewed by the interviewer, in a sealed envelope at the end of the interview.

Although self-report drug use questionnaires have been shown to be generally accurate (19), they are vulnerable to underreporting (20,21). The NHSDA has been shown to elicit a higher reporting rate than non-self-administered questionnaires (22,23) or telephone surveys (24). Moreover, considerable research has been devoted to improving item comprehension on the NHSDA (25). The NHSDA's prevalence estimates are similar to those of the National Comorbidity Survey (26).

The NHSDA's questions mirror six of the seven DSM-IV-TR (27) diagnostic criteria for substance dependence; only the presence of withdrawal symptoms in the previous 12 months was not assessed. In accordance with the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic rules, participants in this study were classified as currently dependent on a substance if they reported experiencing any three of the symptom criteria for dependence on that substance in the previous 12 months. This approach to classification is stricter than that used in clinical practice, because individuals who might have met diagnostic criteria because of their withdrawal symptoms would have to endorse an additional symptom to obtain the three needed for categorization into this group. Individuals who endorsed dependence criteria for cigarettes but not for any other substance were not included in this sample.

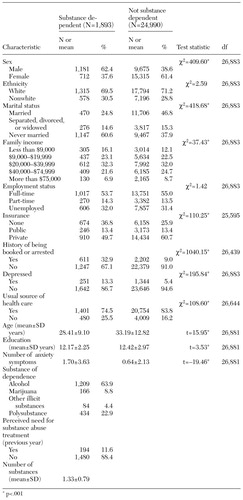

With the use of this classification system, a total of 1,893 (7 percent) of the adults surveyed met the diagnostic criteria for dependence on at least one substance, excluding cigarettes. As Table 1 shows, this group was significantly different in many respects from the non-substance-abusing adults in the NHSDA sample. They were more likely to be younger, less educated, uninsured, never married, and male and to have lower family incomes. They were more likely to report involvement with the legal system and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Alcohol was the most common substance of dependence in this group. Despite currently meeting dependence criteria, relatively few perceived themselves as currently needing help for drug or alcohol problems.

The NHSDA also contains a number of questions that replicate the diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode, as outlined in DSM-IV-TR (27), except for the symptom of psychomotor agitation or retardation. For the purposes of this study, individuals were classified as being depressed if, in accordance with DSM-IV-TR, they reported a two-week period during which they exhibited four symptoms characteristic of a major depressive episode in addition to either depressed mood or anhedonia. According to this categorization rule, 13.3 percent of the dependent group was also classified as having been depressed in the previous year. Although the NHSDA contains a number of questions assessing symptoms characteristic of generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, and agoraphobia, too few questions were asked to permit the classification of individuals as having any particular anxiety disorder. Hence a summary score of the number of anxiety symptoms experienced during the previous 12 months was created. Substance-dependent individuals reported a mean of 1.70±3.63 anxiety symptoms.

Finally, participants were asked a number of questions about treatment: "How many times in the past 12 months have you received treatment or counseling for your use of alcohol or any drug, not counting cigarettes?" "During the past 12 months, how many times have you stayed overnight or longer in a hospital to receive treatment for psychological or emotional difficulties?" "Have you received treatment for psychological problems or emotional difficulties at a mental health clinic or by a mental health professional on an outpatient basis in the past 12 months?" In this study, the latter two items were combined so that participants were counted as receiving care in the mental health system if they endorsed either item; receipt of any treatment was defined as responding in the affirmative to any of the three questions. No minimum duration was necessary for the services to be classified as treatment.

Data analyses

A stepwise logistic regression using the Wald statistic was used to identify demographic and clinical variables that significantly predicted any type of substance or mental health treatment within the previous year among individuals classified as having substance dependence. A similar analytic strategy was used to investigate the variables that best predicted the use of mental health treatment only as opposed to care that included specialized substance abuse services. Univariate tests were used to further describe the subgroup of persons who used only mental health treatment.

Results

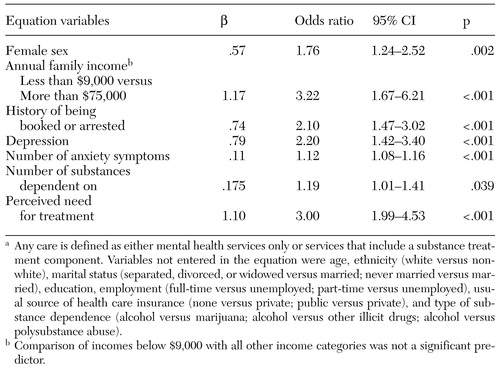

Among individuals who were classified as currently substance dependent, only 18.3 percent reported receiving any type of treatment in the previous 12 months. A stepwise logistic regression using the Wald statistic found several variables to be predictive of treatment, yielding an overall classification rate of 89.2 percent (χ2=179.50, df=10, p<.001). As outlined in Table 2, sex and income each played a significant role. Women were more likely than men to be enrolled in treatment (odds ratio [OR]=1.76). Persons with an annual family income above $75,000 were three times as likely to be enrolled in some type of treatment as those whose annual income was less than $9,000. Having a history of being booked or arrested was associated with a higher likelihood of receiving care, as was the number of substances on which the person was dependent. The presence of symptoms of depression or anxiety were associated with a higher likelihood of receiving some type of treatment. Those who were classified as concurrently depressed were more than twice as likely to receive services as those who were not depressed. Substance-dependent individuals were three times as likely to obtain any type of care if they perceived themselves as currently needing treatment for addiction.

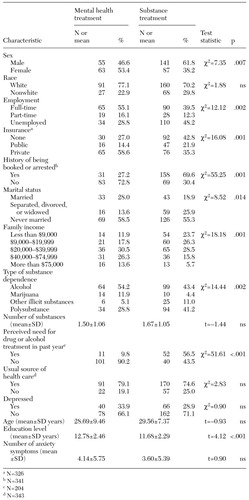

Among those who received care, the type of care they received was also interesting. About a third (34.1 percent) of the respondents whose self-reported current symptoms indicated substance dependence reported having received only mental health care in the previous year rather than substance abuse treatment. The remaining respondents reported receiving treatment specifically for substance abuse (46.2 percent) or receiving both substance and mental health services (19.7 percent) during the previous year.

To determine whether any of the same array of variables outlined in the previous analysis were predictive of the type of care used in the previous year, a stepwise logistic regression using the Wald statistic was used. Four factors were found to be significantly associated with the likelihood that the substance-dependent individual would obtain only mental health treatment (χ2=83.95, df=5, p<.001). Compared with persons who had private insurance, those who used public insurance or were uninsured were significantly less likely to be treated in a service system characterized as having solely a mental health focus (OR=.27, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=.10 to .76 and OR=.33, CI=.14 to .77, respectively). Having a history of being booked or arrested (OR=.28, CI=.13 to .60) or perceiving oneself as needing help with drug or alcohol problems (OR=.12, CI=.05 to .28) also were associated with lower odds of receiving mental health treatment. A higher educational level, in contrast, was associated with a higher likelihood of obtaining mental health treatment only (OR=1.22, CI=1.03 to 1.44). The combination of these variables yielded an overall classification rate of 80.3 percent.

To characterize more fully the group who reported current symptoms of substance dependence but did not obtain treatment that specifically contained a substance dependence component, univariate analyses were conducted. As Table 3 shows, in addition to having the aforementioned characteristics, these individuals were more likely to be married women who were employed full-time. Their family income was substantially higher on average, with nearly 40 percent of those using only the mental health service system having an annual family income of $40,000 or more. By contrast, 50 percent of those who received services with a substance dependence component had annual family incomes below $20,000. Finally, those who used only the mental health system tended to report more problems with alcohol or marijuana than with other illicit drugs or with polysubstance abuse. Neither being classified as having depression nor the number of symptoms of anxiety was associated with the likelihood that an individual would obtain care from only the mental health system.

Discussion

In a nationally representative household sample, 7 percent of adults surveyed met the diagnostic criteria for dependence on at least one substance, excluding cigarettes, in the previous year. This rate is similar to those found in other comparable samples (28). Of this group, only 18.3 percent reported receiving any type of treatment in the previous 12 months.

Consistent with other findings reported in the literature (3,5,6,9,10), female sex, depression, presence of a number of anxiety symptoms, and a history of being booked or arrested all were associated with a higher likelihood of receiving treatment. Very high income as compared with very low income also was predictive of treatment use. This finding is in contrast with the findings of previous work (7), although the apparent discrepancy may be attributable simply to the greater differentiation at the upper end of the NHSDA income scale than in the measurement instruments used in other work. Substance-relevant factors that predicted treatment use were the number of substances on which the individual was dependent and the individual's perception of needing help for drug or alcohol problems.

Just as interesting as the factors that motivate an individual to seek any care, however, are the factors that predict the type of care they receive. This study suggests that some patients' care should be redirected or reconceptualized, because nearly a third of the respondents with substance dependence in this sample were in treatment that they reported was not designed specifically to address addiction. When a variety of demographic and clinical variables are taken into account, a picture emerges of the individual who reports symptom consistent with substance dependence yet seeks mental health care that does not include an explicit substance abuse treatment component. This individual is more likely to be a married female of higher socioeconomic standing. There is less likely to be a history of involvement with the legal system. The problematic substances are more likely to be alcohol and marijuana than other, potentially more socially stigmatizing, illicit drugs or polysubstance abuse. In this sample, 90 percent of those receiving only mental health care denied the need for help with drug or alcohol problems.

A number of explanations for this mismatch between patient and service sector have been proposed, focusing variously on issues of availability, referral, perception of need for substance abuse treatment services, and out-of-pocket expenditures. Hoff and Rosenheck (29) argued that cost-cutting trends in health care may reduce the availability of certain types of specialty care, with the result that certain patients are shifted to more generalized psychiatric care. Although the annual growth rate in spending for mental health between 1986 and 1996 exceeded that of alcohol treatment (7.3 percent compared with 1.7 percent), this was not the case for primary drug or combined drug and alcohol services (13.2 percent) (16).

Others suggest a system referral bias. Research has shown that people who have dual diagnoses are more likely to be referred for mental health care than for substance abuse care (14,30), and some authors have speculated that the psychiatric component in many individuals' symptoms so dominates that it has led to funneling—by patients or by professionals—into the mental health treatment system rather than into the substance abuse treatment system (10). However, the fact that persons in this sample who obtained only mental health care were not more likely to be classified as depressed or to report more anxiety symptoms seems, to some extent, to counter the hypothesis that such funneling is occurring.

A third explanation is that certain groups, particularly women, find the idea of psychiatric problems more palatable than that of substance abuse problems and hence gravitate toward mental health services (30,31,32). In this sample, respondents with dependence who reported receiving mental health care without a substance abuse treatment component were more likely to be married women whose problems were with alcohol or marijuana rather than with the use of multiple substances or other illicit drugs. Very few reported themselves as currently needing help with a drug or alcohol problem. Moreover, these individuals were more likely to be from more affluent socioeconomic backgrounds, which would be consistent with previous studies that have shown that persons who obtain mental health treatment generally must provide a larger percentage of out-of-pocket expenditures than those who receive substance abuse treatment (16).

It may be that persons in this subpopulation tend to use mental health services because they realize that they have a problem but are unable to see themselves as "alcoholics" or "drug addicts," given their mental image of such individuals. Their greater economic resources enable them to use the mental health services that are more palatable to them. If further research bears out these speculations, it would suggest the need to alert mental health practitioners to the needs of this type of patient so that treatment strategies can be used that might enable these patients to address their substance problems more overtly.

Several limitations, mostly having to do with the structure of the NHSDA questions, must be noted. Although they closely mirror the DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance dependence and major depressive disorder, the questions in the NHSDA do not duplicate them exactly, which could lead to some degree of misclassification. Moreover, because other psychiatric disorders are not addressed in the NHSDA, the full role of comorbid psychiatric illness cannot be explored. Greater precision in the timing of events would also have been helpful. Although the substance dependence, psychopathology, and treatment questions used the previous 12 months as the time frame, the NHSDA did not allow for greater specificity.

The NHSDA also did not contain any items specifically inquiring whether the individual's substance use had been discussed in any way in mental-health-only treatment. The NHSDA relies on the individual's perceptions of which type of treatment they used rather than on a formal definition of each type of service. However, the item order would seem to have assisted in differentiating the types of service. The mental health treatment questions in the NHSDA follow an item that asks whether substance abuse services had been received in a mental health clinic. Finally, as alluded to earlier, self-report questionnaires about substance use are susceptible to some underreporting biases.

Conclusions

Longitudinal studies that could track individuals' routes of service contacts and conceptualization of the nature of their problems, including their perception of need, would likely shed light on how to better provide more specific treatment services for persons with substance dependence. This study represents a first step toward understanding the role of demographic and clinical variables in access to care among substance-dependent individuals.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Kevin D. Hennessy, Ph.D., for comments on an earlier version of this article and Jennifer Yates, M.A., for data management assistance.

Dr. Green-Hennessy is assistant professor in the department of psychology at Loyola College in Maryland, 4501 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21210 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of a sample of adults with and without substance dependence

|

Table 2. Stepwise logistic regression of variables predictive of receiving any type of care during the previous year among adults with current symptoms of substance dependence (N=1,596)a

a Any care is defined as either mental health services only or services that include a substance treatment component. Variables not entered in the equation were age, ethnicity (white versus nonwhite), marital status (separated, divorced, or widowed versus married; never married versus married), education, employment (full-time versus unemployed; part-time versus unemployed), usual source of health care insurance (none versus private; public versus private), and type of substance dependence (alcohol versus marijuana; alcohol versus other illicit drugs; alcohol versus polysubstance abuse).

|

Table 3. Demographic and clinical differences between persons with substance dependence who received mental health treatment or substance-specific treatment in the previous year (N=346)

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse: The economic costs of alcohol and drug abuse in the United States, 1992. Available at: http://165.112.78.61/EconomicCosts/Chapter1.htmlGoogle Scholar

2. Stein JJ: Substance Abuse: The Nation's Number One Health Problem: Key Indicators for Policy Report. Princeton, NJ, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2001Google Scholar

3. Ross HE, Lin E, Cunningham J: Mental health service use: a comparison of treated and untreated individuals with substance use disorders in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:570-577, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Narrow WE, Regier DA, Norquist G, et al: Mental health service use by Americans with severe mental illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:147-155, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD: Untreated opiate addicts: how do they differ from those seeking treatment? Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1072-1077, 1985Google Scholar

6. Schutz CG, Rapiti E, Vlahov D, et al: Suspected determinants of enrollment into detoxification and methadone maintenance treatment among injecting drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 36:129-138, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Weisner C: Toward an alcohol treatment entry model: a comparison of problem drinkers in the general population and in treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 17:746-752, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kaskutas LE, Weisner C, Caetano R: Predictors of help seeking among a longitudinal sample of the general population, 1984-1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 58:155-161, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Finney JW, Moos RH: Entering treatment for alcohol abuse: a stress and coping model. Addiction 90:1223-1240, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17-31, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Moggi F, Ouimette PC, Finney JW, et al: Effectiveness of treatment for substance abuse and dependence for dual diagnosis patients: a model of treatment factors associated with one-year outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 60:856-866, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Ouimette PC, Moos RH, Finney JW: Two-year mental health service use and course of remission in patients with substance use and post-traumatic stress disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61:247-253, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Schmidt L: A profile of problem drinkers in public mental health services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:245-250, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Solomon P: Receipt of aftercare services by problem types: psychiatric, psychiatric/substance abuse, and substance abuse. Psychiatric Quarterly 58:180-188, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Moos RH, Mertens JR, Brennan PL: Rates and predictors of four-year readmission among late-middle-aged and older substance abuse patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 55:561-570, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. McKusick D, Mark TL, King E, et al: Spending for mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1996. Health Affairs (Milwood) 17:147-157, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Dixon L, McNary S, Lehman A: One-year follow-up of secondary versus primary mental disorder in persons with comorbid substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1610-1612, 1997Link, Google Scholar

18. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1995 and 1996. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. [Data file distributed by the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research in Ann Arbor, Mich, 1998]Google Scholar

19. Hser Y: Self-reported drug use: results of selected empirical investigations of validity, in The Validity of Self-Reported Drug Use: Improving the Accuracy of Survey Estimates. NIDA Research Monograph 167. Bethesda, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1997Google Scholar

20. Harrell AV: The validity of self-reported drug use data: the accuracy of responses on confidential self-administered answer sheets, in ibidGoogle Scholar

21. Harrison L, Hughes A: Introduction: the validity of self-reported drug use: improving the accuracy of survey estimates, in ibidGoogle Scholar

22. Rogers SM, Miller HG, Turner CF: Effects of interview mode on bias in survey measurements of drug use: do respondent characteristics make a difference? Substance Use and Misuse 33:2179-2200, 1998Google Scholar

23. Turner C, Lessler J, Devore J: Effects of mode of administration and wording on reporting of drug use, in Survey Measurement of Drug Use. Edited by Turner CF, Lessler JT, Gfroerer JC. Washington, DC, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1992Google Scholar

24. Gfroerer JC, Hughes AL: Collecting data on illicit drug use by phone, in ibidGoogle Scholar

25. Hubbard M: Laboratory experiments testing new questioning strategies, in ibidGoogle Scholar

26. Office of Applied Studies Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Advance Report No 18. Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/nhsda/PE1996/rtst1020.htmGoogle Scholar

27. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2000Google Scholar

28. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Long-term patterns of service use and cost among patients with both psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Medical Care 36:835-843, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lehman AF, Meyers CP, Johnson J, et al: Service needs and utilization for dual-diagnosis patients. American Journal of Addictions 4:163-169, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Thom B: Sex differences in help-seeking for alcohol problems: I. The barriers to help-seeking. British Journal of Addictions 81:777-788, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Weisner C, Schmidt L: Gender disparities in treatment for alcohol problems. JAMA 268:1872-1876, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar