Lessons Learned From Trends in Psychotropic Drug Expenditures in a Canadian Province

Abstract

Although prescription drug prices are lower in Canada than in the United States, trends indicate that there has nevertheless been a steep increase in expenditures on psychotropic drugs. Between 1992 and 1998, such expenditures increased by 216 percent; 61 percent of these expenditures were on antidepressants, 33 percent on antipsychotics, and less than 7 percent on anxiolytics. Most of the increase in costs in Canada is attributable to a greater use of newer agents and the higher prices of these agents. These trends are a reminder not only that the use of newer, more expensive psychotherapeutic agents has become a widely embraced part of care but also that lower drug prices do not necessarily insulate a health care system from rising expenditures. The authors' findings prompt the questions of whether the use of these newer agents meets practice guidelines and whether there are ways to control the increases in drug expenditures while ensuring high-quality care.

Prescription drug prices are more actively controlled by the government in Canada than is the case in the United States. For example, the Canadian Patented Medicines Prices Review Board is a federal regulatory agency whose main purpose is to control the prices of patented drugs by ensuring that prices of prescription medications remain low. Each province also has its own price control mechanisms for prescription drugs. Consequently, most of Canada's prices for patented prescription medications are lower than those in the United States. A comparison of U.S. and Canadian prices for three of the ten most frequently used drugs in the United States in 1999—fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine—indicates that persons who live in the United States can pay between 46 percent and 53 percent more for an average daily dose of one of these three antidepressants (1).

Despite price controls, the proportion of Canada's national health budget that is spent on prescription drugs has grown (2). In the context of rising overall drug expenditures and the growing popularity of psychotherapeutic agents and antidepressants in particular, we examined expenditures on psychotropic drugs in Ontario between 1992 and 1998. In this report we describe increases in expenditures on psychotropic drugs and the contribution of various classes of psychotropic drugs to this growth.

Background

Although the Canada Health Act guarantees health care coverage to all persons, pharmaceuticals are not included. This omission has created a system of payers similar to that in the United States—a split among employer-sponsored private insurance plans, public benefits, and payment by the individual patient. In 1996 the public sector accounted for about 36 percent of all prescription drug expenditures (3).

In Ontario, publicly sponsored benefits are administered by the Ontario Drug Benefits Program (ODB). This program serves primarily two populations: the elderly and the financially disadvantaged. From 1992 to 1998, approximately two million claimants—about 20 percent of Ontarians—who represented around 44 million annual claims, used ODB benefits.

ODB has means-tested eligibility requirements for nonseniors; these requirements are linked primarily to public assistance programs. In addition, ODB has a sliding deductible-fee scale that is a function of family size and income, as well as an income-dependent dispensing fee that can range from $2 to $6.11. The program uses a restricted formulary of 3,000 drugs for physical and mental disorders.

Between 1989 and 1996, several new antidepressants and antipsychotics were added to the ODB formulary. Included were four antidepressants from the family of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline—which were introduced between 1989 and 1995. Three new atypical antipsychotics—risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine—were introduced between 1993 and 1996. Physicians readily embraced these new agents because their adverse effects were perceived to be more tolerable than those of the older drugs, which would lead to better compliance. In addition, clinical treatment guidelines have recommended these drugs as first-line agents. At the same time, their average daily costs were often higher than those of the older agents.

Methods

Using drug claims data from ODB's administrative database from 1992, 1995, and 1998, we compared expenditures for three major classes of psychotherapeutic drugs: anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and antidepressants. Antipsychotics included both typical and atypical agents. Although clozapine is usually included among antipsychotics, ODB has a special program for clozapine users, so the claims of these users did not appear in the database we used. Antidepressants included SSRIs, tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other antidepressants.

Results

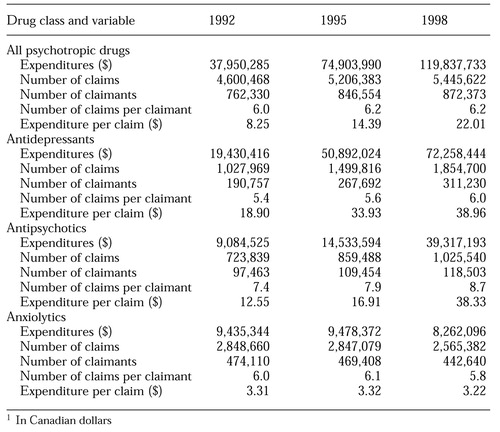

As can be seen in Table 1, psychotropic drug expenditures increased sharply between 1992 and 1998. In 1992 ODB spent almost $38 million Canadian on psychotropic drugs. About 51 percent of this sum was spent on claims for antidepressants, 24 percent for antipsychotics, and 25 percent for anxiolytics. By 1998, total psychotropic drug expenditures had increased by 216 percent to almost $120 million; 61 percent of these expenditures were on antidepressants, 33 percent on antipsychotics, and less than 7 percent on anxiolytics.

The growth in total expenditures on psychotropic drugs was driven by two key subclasses of drugs: new SSRIs and new atypical antipsychotics. The SSRIs accounted for 85 percent of the increase in expenditures between 1992 and 1995 and for 50 percent of the increase between 1995 and 1998. The role of the new atypical agents is underscored by the fact that there were no claims for these drugs in 1992, whereas by 1995 they were responsible for 19 percent of total psychiatric drug costs. By 1998, the new atypical agents accounted for almost 33 percent of psychiatric drug costs.

Did greater use of antipsychotics in general or use of expensive newer antipsychotics in particular contribute to this tremendous increase in expenditures? If greater use in general was the driving force, we should observe at least one of three trends: an increase in the total number of claimants as a result of more people using ODB benefits, an increase in the number of drugs used, or an increase in the number of claims per claimant.

On the other hand, if the use of new expensive drugs was the catalyst for the increase, we would expect the expenditure per claim to have increased. However, this would not be a definitive indicator if drug prices had increased substantially during the same period: an increase in expenditure per claim could reflect price changes rather than the use of more expensive, newer drugs. However, during this period, changes in drug prices due to inflation were only moderate. Between 1992 and 1997, changes in the prices of patented drugs fluctuated between -2.2 percent and 2.1 percent (4).

Although the use of antidepressants in general and the use of more expensive, newer antidepressants increased, the latter was the more important element. Between 1992 and 1998, expenditure per claim increased by 106 percent, while the number of claims increased by 80 percent, the number of claimants by 63 percent, and the number of claims per claimant by 3 percent.

For antipsychotics, the contrast is more dramatic. Between 1992 and 1998, the number of claims increased by 42 percent, the number of claimants by 22 percent, the number of claims per claimant by 11 percent, and expenditure per claim by 205 percent. Thus although the number of claims, claimants, and claims per claimant increased during this period, expenditure per claim increased by an even greater proportion. The magnitude of change in this variable suggests that it is unlikely that all the growth can be attributed to moderate price changes due to inflation during this period.

Discussion

Despite the use of price controls, psychotropic drug expenditures increased sharply in Canada between 1992 and 1998, in association with both a higher expenditure per claim and a greater number of claims. As in the United States (5), most of the additional expenditures are attributable to the higher costs per claim associated with the use of the more costly newer agents.

These findings offer two valuable lessons. First, they underscore the fact that over the past few years, standard and recommended care have involved the prescription of newer, more costly psychotherapeutic agents. This trend highlights the importance of drug benefit coverage, especially for individuals who have low incomes and households that do not qualify for means-tested benefits and do not have access to employment-related insurance (6). For example, in 1998 the average Canadian household spent about $1,190 Canadian on health care (7). A year's supply of sertraline, one of the most widely used SSRIs, could cost between $584 and $1,223. A year's supply of risperidone, the most widely used atypical antipsychotic, could cost between $173 and $2,074. An average household without insurance could use all of its health care budget on one family member, which could lead to tighter constraints on household resources and require trade-offs among family members.

Second, the trends illustrate that aggressive price controls do not necessarily insulate a health care system from increasing expenditures. A health care system that is committed to guaranteeing access to guideline-recommended pharmacotherapeutic treatments must confront inevitable growth in prescription drug expenditures—the reality is that providing newer, higher-quality agents will cost more.

At the same time, it must be emphasized that it would be shortsighted to focus solely on the increase in drug expenditures. Although the database we used did not allow us to determine changes in patterns of service use and treatment compliance that were associated with changes in prescription drug use, the literature provides evidence that the newer psychotropics are associated with less use of other health care services and with greater compliance (8,9,10). These changes in total health care use could offset greater drug expenditures, ultimately resulting in lower total health care expenditures.

Conclusions

Although Canada's drug prices are controlled, total expenditures on psychotropic drugs have nevertheless increased sharply in recent years. This trend highlights the fact that during this period standard care has become associated with the prescription of newer, more costly psychotherapeutic agents. Second, despite price controls, offering people access to higher-quality, newer psychotherapeutic agents will be associated with an increase in prescription drug expenditures.

Our findings prompt several important questions. For example, if these newer psychotherapeutic agents have been embraced as standard care, is their use meeting practice guidelines? In addition, are there ways to control the growth in drug expenditures while ensuring high-quality care? Answers to these questions will provide decision makers with crucial information as they develop policies that affect the quality of life for people who have mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Streiner, Ph.D., and Elizabeth Lin, Ph.D., for helpful comments and suggestions. The data for this project were provided by Brogan, Inc.

The authors are affiliated with the Clarke site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the department of psychiatry of the University of Toronto, 250 College Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5T 1R8 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Expenditures on psychotropic medications in Ontario, Canada, between 1992 and 1998, according to data from a public drug benefit program's administrative drug claims database1

1 In Canadian dollars

1. Cauchon D: Americans pay more: here's why. USA Today, Nov 10, 1999, pp 1A-2AGoogle Scholar

2. Total health expenditures. Canadian Institute for Health Information Web site. Available at http://www.cihi.ca/facts/nhex/attach1.shtml , /attach2.shtml, and /attach3. shtmlGoogle Scholar

3. Dingwall DC: Drug Costs in Canada. Ottawa, Canadian Ministry of Health, Mar 1997Google Scholar

4. Covari RJ: Trends in Patented Drug Prices. Study series S-9811. Ottawa, Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, Sept 1998Google Scholar

5. Levit K, Cowan C, Braden B, et al: National health expenditures in 1997: more slow growth. Health Affairs 17(6):99-110, 1998Google Scholar

6. Foxman B, Valdez R, Lohr K, et al: The effect of cost sharing on the use of antibiotics in ambulatory care: results from a population-based randomized controlled trial. Journal of Chronic Disease 40:429-437, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Statistics Canada: Household spending, dwelling characteristics, and household facilities. The Daily, Dec 13, 1999, pp 1-6Google Scholar

8. Conley RR, Love RC, Kelly DL, et al: Rehospitalization rates of patients recently discharged on a regimen of risperidone or clozapine. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:863-868, 1999Link, Google Scholar

9. Sturm R, Wells K: How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA 273:51-58, 1995Google Scholar

10. Zito JM: Pharmacoeconomics of the new antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 21:181-202, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar