Best Practices: Dissemination of Guidelines for the Treatment of Major Depression in a Managed Behavioral Health Care Network

Numerous treatment guidelines have been developed in the past decade to address the accumulating evidence of variation in clinical practice and quality of care for the treatment of major depression and other mental and medical disorders. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1) recently reported that the National Guideline Clearinghouse, an Internet-based resource, now offers access to more than 700 evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on its Web site. As organizational and individual accountability becomes a greater priority in today's service delivery systems, it is important to understand how to achieve adherence to guidelines and greater consistency in clinical practice.

Previous studies that examined methods for influencing clinicians' behavior have shown that traditional continuing education tools, such as mailed materials, workshops, and conferences for physicians, have little impact (2). More intensive interventions, such as interactive continuing education sessions through which clinicians can practice the skills they have learned, seem more effective and may influence health care outcomes (3,4).

Highly respected leaders of opinion (5), academic detailing (6), and continuous quality improvement teams (7) have also been shown to be more influential in changing physicians' behavior than education alone. However, given that most mental health specialists are unaffiliated, provide care in private offices, and belong to numerous open managed care networks, it would be unrealistic to rely on the use of academic detailing and continuous quality improvement in large decentralized delivery systems. Few studies of effective dissemination of guidelines as a strategy for influencing psychiatrists' clinical practice have been published, and there have been no studies of nonphysician mental health practitioners.

Managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) provided coverage to 176 million people (8) in 1999. They are thus in a unique position in the mental health services system to study clinicians' behavior in real-world settings. Studying dissemination of guidelines in an MBHO provides access to a large population of patients throughout the United States who are treated by a representative sample of independent clinicians who have different backgrounds and clinical experience. We sought to determine whether clinicians read guidelines disseminated by MBHOs and, if so, whether they find such guidelines helpful.

Methods

Development of guidelines

In 1999, the United Behavioral Health (UBH) best-practice guidelines for the treatment of major depression were compiled with the use of guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) as well as the latest research on the treatment of major depression. The guidelines were sent for internal and external review by a panel of academic and clinical practice experts. The UBH guidelines consist of a one-page quick-reference sheet and an eight-page reference booklet (available from the authors on request).

Design overview

This study used a randomized controlled design to test two dissemination methods for the guidelines. Clinicians in the general dissemination group received the UBH guidelines in a single mass mailing. Clinicians in the target dissemination group received the UBH guidelines that specifically targeted a patient, recently referred by the MBHO, whom they had diagnosed as having major depression. A control group of clinicians did not receive any guidelines. We chose this design to test whether clinicians were more likely to read and use guidelines that target a specific patient when the guidelines were sent by an MBHO. All clinicians were surveyed four months after they received the guidelines.

Participants

Clinicians from the UBH network were randomly selected for the study from the provider panel and were included if they had seen at least five adult patients with major depression in the 12 months before the start of the study and if they had submitted a claim for one adult patient with a new episode of major depression—that is, a patient who had received no services in the previous 90 days—within 30 days of the start of the project (September 1999). A total of 443 clinicians were included in the study.

Procedures

Simple randomization was used to give each clinician an equal chance of being assigned to each of the three groups; however, it produced groups of unequal sizes: 162 were assigned to the general dissemination group, 132 were assigned to the target dissemination group, and 149 were assigned to the control group. Clinicians' age, sex, and state of residence were comparable among the three groups. A significantly greater proportion of psychiatrists than other clinicians were randomly assigned to the control group (82 percent) than to the general dissemination group (72 percent) or the target dissemination group (70 percent) (p<.05).

Guideline dissemination

Clinicians in the general dissemination group were sent a single mass mailing of the UBH best-practice guidelines with a cover letter stating that the guidelines were for their review in the treatment of their patients. Clinicians in the target dissemination group received the same guidelines with a similar cover letter stating that the guidelines were sent for their review in the treatment of a particular patient, who was named in the letter. Both letters highlighted various points covered by the guidelines, explained the study, and informed the clinicians that they and their patients would be surveyed four months later.

Measures

The mailed follow-up survey for the clinicians in the general and targeted dissemination groups asked the clinicians whether they had received and read the guidelines and to rate the guidelines' usefulness. Respondents who had not read the guidelines were asked to indicate reasons for not doing so. The clinicians in the control group were asked similar questions in relation to the APA or AHCPR guidelines.

Results

Of 443 clinicians in the study, 323 (73 percent) responded to the survey. An initial response rate of 46 percent after two mailings was increased by using Dillman's survey methods (9), which involved adding one telephone follow-up and a final follow-up mailing. No significant differences in age, sex, state of residence, or group assignment were observed between clinicians who did and did not respond to the survey. However, a significantly greater proportion of psychologists (89 percent) and master's-level therapists (88 percent) than psychiatrists (68 percent) (p<.001) responded to the survey. The mean±SD age of the respondents was 50.8±9.9 years. A total of 200 respondents (62 percent) were men, and 243 (75 percent) lived in California, Pennsylvania, Ohio, or Massachusetts, the states in which UBH has its greatest concentration of members. The clinicians had a mean±SD number of years in practice of 15.6±9.9 and belonged to 7.8±7.3 managed care panels (range, one to 50). The type of license was controlled for in all group comparisons because it was somewhat confounded by group assignment.

Do clinicians read guidelines?

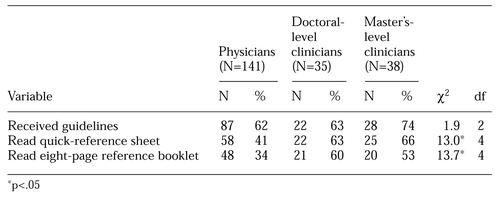

Only 137 (64 percent) of the 214 respondents in the general and targeted dissemination groups reported having received the UBH guidelines. Even fewer reported that they had read the guidelines: 105 (49 percent) had read the quick-reference sheet, and 89 (42 percent) had read the reference booklet. No significant difference was observed between the general and targeted dissemination groups in their report of having received or read the guidelines. However, as Table 1 shows, psychiatrists were less likely to have received or read the UBH guidelines than psychologists or master's-level therapists. Of the 24 clinicians in the general and targeted dissemination groups who reported reasons for not reading the UBH guidelines, most (23 clinicians) reported being "too busy to read them," and nine indicated that "UBH should not tell me how to practice."

Clinicians in the control group, who did not receive the UBH guidelines, were asked whether they had read published guidelines. Most respondents (84 percent) reported that they had read APA guidelines, and only 40 percent reported that they had read AHCPR guidelines. A significantly greater proportion of psychiatrists (89 percent) and psychologists (83 percent) reported having read APA guidelines than master's-level therapists (61 percent). Of the 28 clinicians in the control group who provided reasons for not having read the guidelines, 13 indicated that they had "never heard of AHCPR or APA guidelines" and seven indicated that "others should not tell me how to practice."

Do clinicians find guidelines helpful?

Overall, 130 clinicians (67 percent) who had read any guidelines rated such guidelines as useful to their practice. Logistic regression showed no significant difference in the effect of the type of dissemination on the clinicians' ratings of the usefulness of the guidelines when the type of license was controlled for.

Discussion

Our results suggest that guidelines that come from MBHOs may be ineffective in changing clinicians' practices, even when the MBHO sends guidelines that target a particular patient who recently received a diagnosis from the clinician. An important reason for this failure could be that fewer than two-thirds of the clinicians even recalled receiving the UBH guidelines, and only half of those who did receive the guidelines reported having read them.

Guidelines from organizations such as APA and AHCPR did not fare much better. Although a greater proportion of psychiatrists than other types of clinicians had read these guidelines, 11 percent of physicians had not read the APA guidelines, which is consistent with the results of other studies that have shown that 10 percent of physicians in general are unaware of the existence of guidelines (10).

Several of our findings suggest that clinicians reacted negatively to dissemination of the guidelines. The initial response rate of 46 percent indicates resistance to responding to the survey. In addition, respondents' written comments (N=132) were more likely to be negative (N=71) than positive. Among clinicians who received but did not read the UBH guidelines, most (96 percent) gave "too busy" as the main reason, yet only 13 percent of the control group gave this reason for not reading the APA or ACHPR guidelines. These findings suggest that guidelines from MBHOs may be perceived as having less relevance or having a different intention than those from governmental or professional organizations. Furthermore, given that on average clinicians belong to eight provider panels, they may be receiving guidelines from many MBHOs, which may contribute to a negative attitude. Perhaps guidelines sent by MBHOs are perceived more as a cost-containment measure than as an effort to ensure quality of care.

Although this study focused on clinicians' perceptions of the usefulness of guidelines sent by an MBHO, additional studies need to examine whether clinicians actually practice according to guidelines and, if so, the effect on treatment outcome. The ineffectiveness of guideline dissemination suggests that MBHOs still need to find practical ways to monitor dissemination and to provide clinicians with feedback based on standards of care set by their peers. MBHOs have a clinical and fiduciary responsibility to monitor the quality of the care that their members receive, because they are accountable to those who pay for the care as well as to accrediting agencies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Regina Brown-Mitchell, B.A., Julie Burstein, Shanna Packer, B.A., Aisa Ta, B.S., and Rebecca Wade, B.A., for their help with the mailings and data collection.

The authors are affiliated with the behavioral health sciences department at United Behavioral Health, 425 Market Street, 27th Floor, San Francisco, California 94105 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. William M. Glazer, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Number of physicians and doctoral and master's-level clinicians who received and read United Behavioral Health's best-practice guidelines

1. The National Guideline Clearinghouse: Fact sheet 00-0047. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2000. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ngcfact.htmGoogle Scholar

2. Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, et al: Changing physician performance: a systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 274:700-705, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Rost K, et al: Treating depression in staff-model versus network-model managed care organizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1:39-48, 1996Google Scholar

4. Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, et al: Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA 282:867-874, 1999Google Scholar

5. Lomas JL: Do guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. New England Journal of Medicine 321:1306-1311, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A: Translating guidelines into practice: a systematic review of theoretical concepts, practical experience, and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Canadian Medical Association Journal 157:408-416, 1997Google Scholar

7. Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unützer J, et al: Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Affairs 18(5):89-105, 1999Google Scholar

8. Findlay S: Trends: managed behavioral health care in 1999: an industry at a crossroads. Health Affairs 18(5):116-124, 1999Google Scholar

9. Dillman DA: Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Toronto, Wiley, 2000Google Scholar

10. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al: Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 282:1458-1465, 1999Google Scholar