Benefits in Behavioral Health Carve-Out Plans of Fortune 500 Firms

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the prevalence and nature of behavioral health carve-out contracts among Fortune 500 firms in 1997. METHODS: A survey was conducted of 498 companies that were listed as Fortune 500 firms in 1994 or 1995. A total of 336 firms (68 percent) responded to the survey. Univariate analyses were used to analyze prevalence, types, and amounts of covered services, cost sharing, and benefit limits. A total of 132 firms reported contracting with managed behavioral health organizations; 124 firms answered benefits questions about covered services, cost-sharing levels, and annual and lifetime limits. RESULTS: Most of the plans covered a broad range of services. Cost sharing was typically required, and for inpatient care it was often substantial. Fifteen percent of the firms offered mental health benefits that were below the limits defined in this study as minimal benefit levels, and 34 percent offered substance abuse treatment benefits that fell below minimal levels. The most generous mental health benefits and substance abuse treatment benefits, defined as no limits or a lifetime limit only of $1 million or more, were offered by 31 percent and 20 percent of the firms, respectively. CONCLUSIONS: The carve-out contracts of the Fortune 500 firms in this study typically covered a wide range of services, and the benefits appeared generous relative to those reported for other integrated and carve-out plans. However, these benefits generally did not reach the level of parity with typical medical benefits, nor did they fully protect enrollees from the risk of catastrophic expenditures.

Private employers can separate behavioral health benefits for their employees from other medical benefits by using "carve-outs," which are direct contracts with managed behavioral health organizations. The decision about whether to carve out behavioral health benefits can be complex (1). One rationale for the use of carve-outs is the belief of some employers that, compared with integrated health plans, managed behavioral health organizations may manage costs better and improve the quality of care because of their specialized expertise, their focused utilization management approach, and their ability to shift care to lower-cost providers through specialized networks (2). In addition, managed behavioral health organizations may achieve economies of scale and learning economies through repeated use of the same utilization and profiling protocols with many populations (3,4). Like any specialty vendor, managed behavioral health organizations are likely to have greater familiarity with the specialty provider sector, so they can direct patients to higher-quality and less-expensive providers (5).

Thus purchasers who contract with managed behavioral health organizations may feel less of a need to rely on rigid or arbitrary benefit plan restrictions designed to curtail enrollees' demand for services. When large firms contract with managed behavioral health organizations, they typically can design the contract terms, including the benefit plan. By allowing more generous benefits, employers can achieve the dual goals of allowing more flexible care to the small proportion of enrollees who need behavioral health services and controlling costs overall through the organization's supply-side strategies.

Benefit packages that have strict limits present enrollees with at least three key problems: limited ranges of covered services can mean that optimal treatment is not obtainable; burdensome cost-sharing provisions may create financial barriers to accessing needed care; and low coverage limits for behavioral health may expose consumers to catastrophic expenses, which negates one of the main purposes of insurance coverage (6).

These issues may be especially important for people who need behavioral health care because private insurance benefits for behavioral health services remain more restricted than those for general medical services (7,8). Federal and state legislation aimed at establishing parity for mental health care and—to a lesser extent—substance abuse benefits has not eliminated the problem of unequal benefits. The Federal Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, which was implemented on January 1, 1998, prohibits lower lifetime and annual dollar limits for mental health benefits than for general medical benefits. However, the goal of full parity has not been met, because the law does not mandate that firms even offer behavioral health coverage, does not apply to substance abuse treatment, and allows different limits on outpatient visits and inpatient days—as well as different copayment requirements—for mental health benefits than for medical benefits.

More than 30 states introduced parity legislation in 1997, and 19 states had adopted parity legislation by 1998. However, these laws vary in scope, and most of them exclude substance abuse (9). Furthermore, state mandates do not apply to self-insured plans, which are exempt under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 and which account for about one-third of privately insured enrollees (10). Therefore, carve- outs of behavioral health services to managed behavioral health organizations still represent an important opportunity to expand the range of covered services, eliminate high levels of patient cost sharing, and remove historically low benefit limits.

Although actual access to benefits under managed care plans is mediated through techniques such as specialized utilization management and provider incentives (11), adequate benefit features remain a crucial prerequisite to ensuring adequate service provision. Despite the argument that carving out may allow employers to rely less on benefit restrictions to keep costs under control, it is not clear whether they have done so. In this study, we explored the benefit features in carve-out contracts among Fortune 500 firms.

Methods

The data source for this study was our 1997 survey of the behavioral health arrangements of Fortune 500 firms (12,13). The survey was sent to the 537 firms that appeared on either the 1994 or the 1995 Fortune 500 list. Responses could be submitted by mail or by phone. Of the 537 firms, 41 were deemed ineligible for inclusion in the study because of mergers and acquisitions. Of the remaining 496 firms, 336 (68 percent) responded to the survey, and of these, 132 (39 percent) reported that they had a contract with a managed behavioral health organization in 1997. Contracts solely for services provided by employee assistance programs were not included in this count.

Companies that reported carve-out contracts were asked about their largest contract's characteristics and benefits for in-network services. A total of 124 respondents (94 percent) answered questions about plan benefits, including range of covered services; initial level of cost sharing for inpatient, outpatient, and intermediate (day treatment, intensive outpatient, and residential) care; and lifetime, annual inpatient, annual outpatient, and annual total limits on mental health and substance abuse treatment benefits. The 124 firms' carve-outs covered more than 3 million employees and their dependents.

To calculate benefit generosity levels, we equated day or visit and dollar limits by using published average outpatient and inpatient provider payments from a large managed behavioral health organization in 1996 (14). Univariate descriptive statistics are presented for the prevalence, types, and amounts of covered services, cost sharing, and benefit limits.

Results

The survey results indicated that the 124 firms' carve-out contracts covered a broad range of services. Consumer cost sharing was almost universal—and often substantial. Benefit limits varied widely, with 18 firms (15 percent) and 42 firms (34 percent) offering less than what we considered to be minimal benefits for mental health and substance abuse treatment, respectively. A third of the firms offered relatively unlimited mental health benefits, but only one-fifth did so for substance abuse.

Covered services

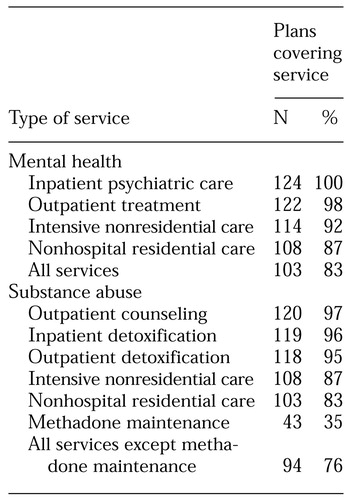

Most carve-out plans covered a wide range of services for mental health care (Table 1). All of the contracts covered inpatient hospital services, and the vast majority covered outpatient psychiatric care, intensive nonresidential care, and nonhospital residential care. More than 80 percent of the contracts offered all four services.

For substance abuse treatment, almost all the contracts included coverage for inpatient detoxification, outpatient therapy or counseling, and outpatient detoxification. Most of the contracts covered intensive nonresidential care and nonhospital residential care. Three-quarters offered all of these services; about one-third covered methadone treatment.

Consumer cost sharing

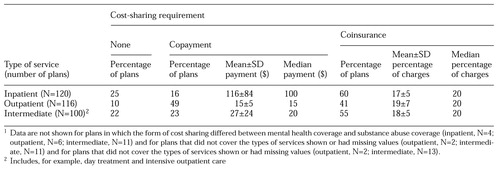

We gathered information on initial copayment and coinsurance for inpatient, outpatient, and intermediate care by in-network providers. Table 2 shows the types and amount of cost sharing for different types of services. Less than one-quarter of the plans had no cost sharing for inpatient and intermediate services, and less than 10 percent had no cost sharing for outpatient services. More than 94 percent of the plans had the same form of consumer copayment or coinsurance for mental health as for substance abuse services.

Benefit limits

Most of the firms, 89 percent, reported some type of limits on behavioral health services. We requested information about four categories of limits for mental health and substance abuse treatment: lifetime, annual inpatient, annual outpatient, and annual total. Limits for mental health services were reported separately if they were different from limits for substance abuse treatment; limits were reported combined if they were the same for both or if there were no limits for either. In every service category, more than 70 percent of respondents reported combined limits and 64 percent had combined limits for all categories.

Generosity of benefits. It is difficult to summarize the generosity of behavioral health benefits, because limits can be combined along at least four dimensions: time period—lifetime or annual; service level—inpatient or outpatient; type of condition—mental health, substance abuse, or combined; and measurement unit—dollars, days, visits, or episodes. Nonetheless, such classification is needed for a broad view of behavioral health benefit limits.

On the basis of discussions with consultants who advise Fortune 500 firms on benefit design, we designated what could be considered a minimal benefit level. Translating benefit limits into dollar equivalencies is useful, given the fact that benefits can often be flexed across settings; for example, inpatient days can be traded for outpatient visits (15).

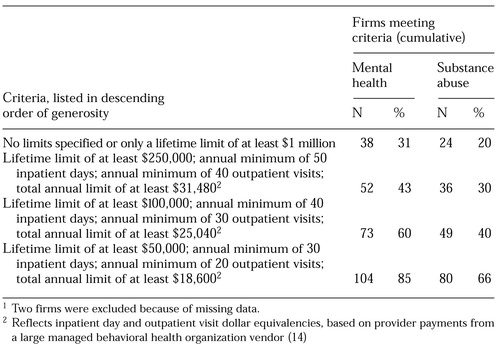

Table 3 presents criteria for generosity of behavioral health benefits and the number of firms that met different levels of criteria. For mental health services, only 15 percent of the firms in our sample failed to offer the minimal level of benefits, defined as a lifetime limit of at least $50,000, at least 30 annual inpatient days (or $17,160), at least 20 annual outpatient visits (or $1,440), and a minimum of $18,600 total annual limits (inpatient plus outpatient).

On the other end of the spectrum, almost a third of the firms offered very generous benefit plans with no specific limits or only a lifetime limit of at least $1 million. For substance abuse services, however, a third of the plans allowed less than the minimal benefit level. About 20 percent offered the most generous level.

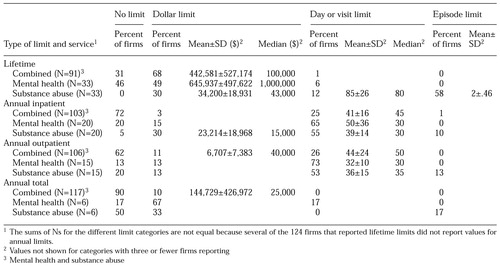

Combined limits. About 31 percent of contracts with combined limits for mental health and substance abuse treatment had no lifetime maximum for behavioral health (Table 4). Those that did specify lifetime limits had a mean limit of $442,581 but a much lower median limit of $100,000, indicating that the mean was influenced by a few firms with extremely high limits. Almost 72 percent of the contracts had no annual limit for inpatient care, 62 percent had no annual limit for outpatient benefits, and almost 90 percent had no total annual limit separate from their inpatient and outpatient limits.

Firms used many different combinations of limits (data not shown). Of the 78 firms that did not differentiate between mental health and substance abuse treatment, 14 (18 percent) had no behavioral health limits at all. The most common limit combinations were a lifetime dollar limit with no other limits (21 firms, or 27 percent) and a lifetime limit and an annual inpatient day limit combined with an annual outpatient visit limit (eight firms, or 10 percent). The remainder had one of 18 other combinations.

Separate limits. Forty-four firms (28 percent) reported different limits for mental health care than for substance abuse treatment in at least one category. For lifetime limits, the average substance abuse treatment benefit was much less generous than the mental health benefit—$34,200 versus $645,937 (Table 4). Moreover, 15 (46 percent) of the firms set no lifetime limits for mental health care, but all of them limited lifetime substance abuse treatment benefits. Nineteen (58 percent) limited coverage of substance abuse treatment episodes to an average of two per lifetime, but no similar restrictions were placed on mental health care.

Discussion

The potential problems imposed on enrollees by restrictive behavioral health benefits provide a framework for discussing the carve-out arrangements in the Fortune 500 firms' contracts. These problems may include a limited range of services, barriers to access because of cost-sharing requirements, and the risk of catastrophic expenses.

The majority of Fortune 500 carve-out plans represented in our survey offered a wide array of services except for methadone maintenance treatment. For example, the percentages of services covered in most service categories were greater than those reported by Buck and colleagues (7) for both carve-out and integrated plans. The differences between our findings and those of Buck and colleagues were especially notable for intermediate care levels and methadone treatment. With this broad array of services, managed behavioral health organizations have the option of substituting less expensive levels of care—when it is clinically feasible—and of tailoring care to individual needs, assuming the purchaser permits this flexibility.

Copayment and coinsurance requirements for services by in-network providers in the carve-out plans in our study were found to be similar to those reported in other studies (16,17), although inpatient cost sharing was higher than in some (15). Outpatient cost sharing did not appear to be unusually high in our study when compared with cost sharing for general medical services in firms with more than 5,000 employees (18). However, the impact of cost sharing on consumers varies according to several factors, including inpatient service use, intensity of outpatient care, and an enrollee's income.

The average $15 outpatient copayment may not be a large burden for some enrollees, although even relatively low copayments have been found to suppress demand for mental health services (19,20). The average coinsurance of 16.7 percent for inpatient care required by almost 60 percent of the plans can be a significant burden, particularly for employees with low incomes or high use of inpatient services. Any behavioral health cost sharing must be considered in the context of an employee's overall health care expenditures, including deductibles and cost sharing for general medical expenses.

Categorizing aspects of the benefit plans in carve-out contracts as being generous or restrictive depends on the comparisons that are being made. From the perspective of achieving parity with medical care, most benefit plans under carve-out contracts still provide far from complete equivalence. As other studies also have found, most plans impose specific limits on behavioral health care (7,16). Our study shows that many carve-out plans in 1997 failed to protect enrollees from catastrophic expenditures.

More than two-thirds of the responding firms used many types of limit combinations, some of which were quite restrictive. Substance abuse treatment benefits, particularly in the lifetime category, tended to be less generous than mental health benefits in the minority of contracts that differentiated between these types of care. Less than one-third of the firms had no specific limits on behavioral health care or they used only lifetime limits of at least $1 million wrapped in with their overall medical limits. These contracts might be construed as "matching" general medical benefit limits, as limits of at least $1 million per covered individual are typical for very large firms (18).

Ideally, the carve-out benefits reported by our sample of Fortune 500 firms could be compared with the behavioral health benefits offered by comparable firms under integrated-non-carved-out health plans. However, the published literature seldom provides both detailed behavioral health benefit information and separate results for very large employers. Because larger employers typically offer more generous benefits, comparing benefits provided by smaller firms may confound differences between carve-out plans and integrated plans. Another relevant comparison can be made with other reported carve-out benefits, although relatively few studies provide such data.

Despite the difficulties in comparing plans, we reviewed several published studies as well as data from KPMG's 1997 Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits Survey (18) for that purpose. The KPMG survey data provide detailed information on behavioral health benefits under carve-out plans in firms with more than 5,000 employees but only limited information on integrated plan benefits. Behavioral health benefits under both carve-out and integrated plans have been reported for firms with ten or more employees (7) and 21 to 27,519 employees (17). Peele and colleagues (16) studied the behavioral health benefits provided under carve-out contracts between 46 firms of unspecified size and a single large managed behavioral health organization. Sturm and McCulloch (15) described benefits under 4,000 carve-out plans administered by a national managed behavioral health organization.

We compared the results from these studies with our own for three important behavioral health benefit limits: annual outpatient visit limits, annual inpatient day limits, and lifetime limits. Not all of the studies reported each limit, but where possible we compared both the percentage of plans using each type of limit and the means within each type. In each category, the benefits reported in our study were similar to or more generous than those in comparison studies for both carve-out and integrated plans. However, because of the differences in the size of the firms, only limited conclusions can be drawn. Furthermore, comparative generosity of the overall benefit package can be determined only by examining the effects of multiple limits.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. The survey was conducted before the Federal Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 took effect. A follow-up survey will focus on 1999 benefits to examine the changes in limits over time. We did not ask about behavioral health benefits available through the firms' general medical plans, so we could not make direct comparisons between behavioral health benefits under carve-outs and under general medical plans. Also, we did not gather data on deductibles.

More broadly, it is important to recognize that benefit features are only part of the story of managed behavioral health care delivery. A full picture would require information about utilization management procedures, pharmacy benefits, actual service use, client satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and providers' perceptions of enrollees' access to services. Nonetheless, this study provides a view of behavioral health carve-out benefits for 124 major employers across a range of managed behavioral health organizations that cover more than 3 million employees and their dependents.

Conclusions

Mental health care and substance abuse treatment insurance benefits have traditionally been more limited than general medical benefits. The advent of managed behavioral health care in the mid-1980s, through carve-out programs in particular, offered purchasers the possibility of managing cost, utilization, and quality through methods other than restricted benefits.

Benefit packages vary among plans, depending on the purchaser's interest and willingness to pay—that is, benefit features are not a fixed characteristic of carve-out plans or their vendors. Large corporations may be motivated to offer relatively generous benefits by the need to retain a highly skilled workforce or in response to pressure from unions. Employers may also be influenced by a vendor's utilization management system, provider network, reputation, and demonstrated track record. Purchasers may be willing to provide more generous benefits because they are confident that costs will not spiral out of control in a carve-out program.

In this study of behavioral health carve-out arrangements among Fortune 500 firms, we examined some key features of behavioral health benefits. Overall, we concluded that most of these carve-out benefit packages offered a broad range of services, but they often had substantial consumer cost-sharing requirements. They usually did not reach the level of parity with typical medical benefits, nor did they fully protect enrollees from the risk of catastrophic expenditures. Most large employers imposed benefit limits, although some companies appeared to be relying on vendors' management techniques rather than on benefit limits to control costs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 1-P50-CA-10233 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse for the Brandeis/Harvard Research Center on Managed Care and Drug Abuse Treatment. The authors thank Suzanne Gelber, Ph.D., Rick Harwood, and Roland Sturm, Ph.D., for their comments on an earlier draft; Jon Gabel, Ph.D., for comparative data; and Laura Altman, Ph.D., Anne Brisson, Ph.D., William Cartwright, Ph.D., Bruce Davidson, M.S.W., Richard Frank, Ph.D., Dennis McCarty, Ph.D., and Matthew Urato, M.S.W., for their help with the survey.

The authors are affiliated with the Schneider Institute for Health Policy of the Heller Graduate School at Brandeis University, MS 035, 415 South Street, Waltham, Massachusetts 02454-9110 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Types of mental health and substance abuse services covered by carve-out plans of 124 Fortune 500 firms

|

Table 2. Cost-sharing requirements for behavioral health services under carve-out plans of Fortune 500 firms in 19971

1 Data are not shown for plans in which the form of cost sharing differed between mental health coverage and substance abuse coverage (inpatient, N=4; outpatient, N=6; intermediate, N=11) and for plans that did not cover the types of services shown or had missing values (outpatient, N=2; intermediate, N=11) and for plans that did not cover the types of services shown or had missing values (outpatient, N=2; intermediate, N=13)

|

Table 3. Generosity of behavioral health carve-out benefits among 122 Fortune 500 firms in 19971

1 Two firms were excluded because of missing data

|

Table 4. Limits for behavioral health benefits under carve-out plans among Fortune 500 firms in 1997

1. Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, et al: Why carve out? Determinants of behavioral health contracting choice among large US employers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27:178-193, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Frank R, McGuire T, Newhouse JP: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50-64, 1995Google Scholar

3. Sturm R: Cost and quality trends under managed care: is there a learning curve in behavioral health carve-out plans? Journal of Health Economics 18:593-604, 1999Google Scholar

4. Vogelsang I: Economic aspects of mental health carve-outs. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2:29-41, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Blumenthal D, Buntin MB: Carve-outs: definition, experience, and choice among candidate conditions. American Journal of Managed Care 4(suppl):45-57, 1998Google Scholar

6. Frank RG, Goldman H, McGuire TG: A model mental health benefit in private health insurance. Health Affairs 11(3):98-117, 1992Google Scholar

7. Buck JA, Teich JL, Umland B, et al: Behavioral health benefits in employer-sponsored health plans, 1997. Health Affairs 18(2):67-78, 1999Google Scholar

8. Jensen GA, Rost K, Burton RPD, et al: Mental health insurance in the 1990s: are employers offering less to more? Health Affairs 17(3):201-208, 1998Google Scholar

9. Sturm R, Pacula RL: State mental health parity laws: cause or consequence of differences in use? Health Affairs 18(5):182-192, 1999Google Scholar

10. Marquis MS, Long SH: Recent trends in self-insured employer health plans. Health Affairs 18(3):161-166, 1999Google Scholar

11. Frank RG, Koyanagi C, McGuire TG: The politics and economics of mental health "parity" laws. Health Affairs 16(4):108-119, 1997Google Scholar

12. Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Merrick EL, et al: Structuring behavioral health care: carved-out or integrated? Compensation and Benefits Management 16:39-46, 2000Google Scholar

13. Merrick EL, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Use of performance standards in behavioral health carve-out contracts among Fortune 500 firms. American Journal of Managed Care 5(suppl):81-90, 1999Google Scholar

14. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17(2):40-51, 1998Google Scholar

15. Sturm R, McCulloch J: Mental health and substance abuse benefits in carve-out plans and the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. Journal of Health Care Financing 24:82-92, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

16. Peele PB, Lave JR, Xu Y: Benefit limits in managed behavioral health care: do they matter? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 24:430-442, 1999Google Scholar

17. Salkever DS, Shinogle J, Goldman H: Mental health benefit limits and cost sharing under managed care: a national survey of employers. Psychiatric Services 50:1631-1633, 1999Link, Google Scholar

18. Gabel J, Hunt K, Kim J, et al: Health Benefits in 1997: Survey of Employer-Sponsored Benefits. Montvale, NJ, KPMG Peat Marwick, 1997Google Scholar

19. Simon GE, Grothaus L, Durham ML, et al: Impact of visit copayments on outpatient mental health utilization by members of a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:331-338, 1996Link, Google Scholar

20. Stein B, Orlando M, Sturm R: The effect of copayments on drug and alcohol treatment following inpatient detoxification under managed care. Psychiatric Services 51:195-198, 2000Link, Google Scholar