State Health Care Reform: Behavioral Health Services Under Medicaid Managed Care: The Uncertain Implications of State Variation

During the past several years most state Medicaid programs began to enroll their beneficiaries in managed care plans. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 accelerated this trend by facilitating mandatory enrollment in managed care and permitting states to contract with health plans that serve populations composed either predominantly or solely of Medicaid enrollees. Although this growth mirrors that of managed care enrollment in the Medicare and commercial health care sectors, the rise in market penetration of Medicaid managed care raises many unique issues because of the structural features of the Medicaid program and the health care needs of those enrolled in it.

In this column we argue that the delivery of mental health and substance abuse services under Medicaid managed care merits particular attention, given the health care needs of those seeking such care and the variety of ways in which states have structured these services. We describe some of the decisions that state Medicaid programs face in the delivery of behavioral health services and discuss the origins and nature of variations among states and the potential implications of different approaches to delivering these services.

Trends in Medicaid managed care enrollment

Just as the overall proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in managed care plans has increased dramatically over the past decade—from 9.5 percent in 1991 to 55.6 percent in 1999—so has the heterogeneity of managed care itself. The level of managed care penetration varies substantially across states. The proportion of the state Medicaid population enrolled in managed care ranges from less than 10 percent in Alaska and Louisiana to more than 85 percent in Arizona and Tennessee (1). In addition, the term "managed care" has many different meanings both within and across states. In some areas, the capitated arrangements under which plans are paid a fixed sum per enrollee exist alongside more loosely managed primary care case management (PCCM) plans. Under PCCM plans, often referred to as "managed fee-for-service plans," primary care physicians are generally paid a monthly management fee for the coordination of care for each Medicaid patient, with services delivered on a fee-for-service basis.

Much of this heterogeneity is driven by the nature of the delivery systems within each state and, more specifically, by the availability of physicians, other health care providers, and health plans willing and able to serve the Medicaid population. These factors and related programmatic decisions determine whether managed care programs operate statewide or only in selected regions of the state and whether enrollment is mandatory or voluntary for various segments of each state's Medicaid population (2).

States also vary with respect to which eligibility groups are enrolled in their Medicaid managed care programs. Initially, most of these programs served only individuals enrolled in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF) and excluded persons with mental and physical disabilities, many of whom are enrolled in the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. Many states adopted this approach for political, fiscal, and administrative reasons, as well as concerns about enrolling a more disabled population in managed care plans that had not previously served large populations with severe conditions (3).

In recent years, more states began to include SSI-eligible individuals in their Medicaid managed care programs, enrolling them in either capitated managed care programs or in the more loosely managed PCCM plans. Several states have also implemented specialty managed care programs that serve SSI-eligible individuals. Such programs include behavioral health carve-outs and specialty programs for persons with disabilities. Each of the decisions about delivering and financing services has direct implications for Medicaid enrollees in need of behavioral health services, many of whom may have particular difficulties navigating managed care systems (4,5).

Organization of services

States generally use one or a combination of three models to deliver mental health and substance abuse services to their Medicaid populations.

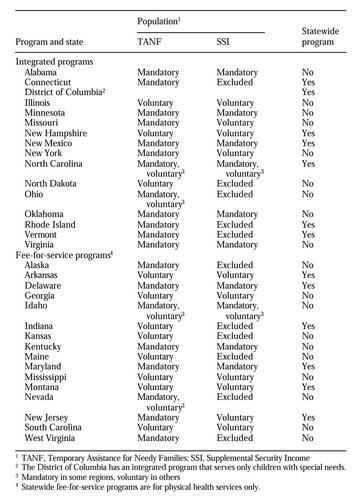

• In integrated programs, the state Medicaid agency contracts with managed care organizations for the delivery of physical health services and at least some behavioral health services; both types of services are covered under a single capitation rate.

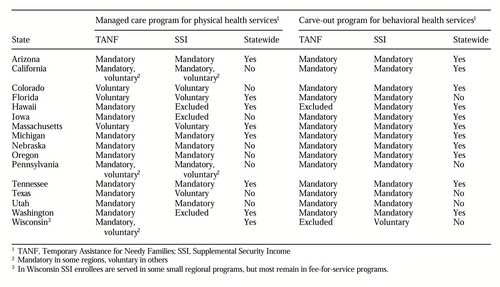

• In carve-out programs, the state or county contracts directly with a specialty health care entity for the delivery of mental health services, substance abuse services, or both. These entities may be private organizations—often called behavioral health organizations—county health departments, or any entity in a range of public-private partnerships created especially for the provision of mental health and substance abuse services to designated populations. In a carve-out, these entities are typically placed at financial risk for the provision of behavioral health services, either on a capitated or a risk-sharing basis. In these states, physical health services may be provided to Medicaid enrollees under separate managed care plans or on a fee-for-service basis.

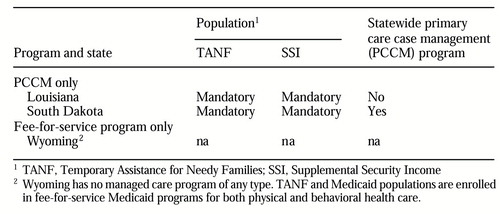

• Fee-for-service programs pay providers on a fee-for-service basis for behavioral health care and do not involve care management of any kind. Of the 19 states that deliver mental health and substance abuse services on this basis statewide, three—Louisiana, South Dakota, and Wyoming—do not have a Medicaid managed care program in operation for physical health services and thus use a traditional fee-for-service program for all health services (Table 1). The other 16 states exclude behavioral health services from the capitated set of services delivered through their Medicaid managed care programs.

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the organizational approaches that state Medicaid managed care programs use to deliver mental health and substance abuse services and include some of the basic features of each state's capitated Medicaid managed care program (or programs). As even the limited information in the tables demonstrates, the simple classification system outlined above obscures much of the variation in states' strategies for delivering behavioral health services to their Medicaid populations.

Overall, the key elements of state programs that likely shape enrollees' experiences in them include, but are by no means limited to, the following features:

• The eligibility groups that are included, such as TANF or SSI enrollees and, if a group is excluded, the alternatives that are available to that group

• Whether enrollment in managed care organizations and, in the case of carve-out programs, behavioral health organizations is mandatory or voluntary for various eligibility groups and, if enrollment is voluntary, the alternatives that are available to those groups

• Whether the program is statewide or operates only in selected regions of the state

• Whether any of the plans holding Medicaid contracts serve a population dominated by or limited to Medicaid enrollees

• Whether mental health and substance abuse services are handled in the same manner—for example, whether substance abuse services are excluded from a state's carve-out program

• Whether the program covers individuals who are not eligible for Medicaid but who are receiving behavioral health care financed either by state-only funds or by block grants.

Assessing the implications of variation

A wealth of descriptive information is available about the ways in which mental health and substance abuse services are delivered by state Medicaid managed care programs (3,6). There is also a growing literature on the impact of programmatic structure on utilization and cost (7,8,9,10,11) and a small but cohesive body of work that raises concerns about managed care's implications for the most severely disabled (12,13). However, relatively little is known about how the different types of programs may influence the quality of mental health and substance abuse services more generally. The many now-familiar arguments for and against the various approaches to the delivery of behavioral health services are most often based on theory or anecdotes, which is partly a result of the practical difficulties of gathering sound outcomes data and the need to track these data over an adequate period.

For example, proponents of carve-outs argue that these arrangements provide behavioral health services more effectively than do integrated managed care programs because they use specialty management services and earmark a pool of funds specifically for mental health and substance abuse care (14). Advocates for an integrated approach, on the other hand, cite barriers to the coordination of physical health and behavioral health care as a disadvantage of carve-out programs (15,16). Needless to say, in the absence of concrete evidence on either side, all of these arguments may be compelling where persons with mental illnesses or substance use disorders are concerned.

In reality, the extent to which the merits of each approach may be supported likely hinges on the health care needs and social service needs of particular groups of enrollees and the expertise and capacity of states to implement programs effectively (17,18).

A key question stemming from the variation among states described here is that of the risks and rewards of variation per se. The Medicaid program was designed on a federal-state basis to accommodate states' unique needs and capacities. In many ways, managed care has allowed even greater potential for heterogeneity in state Medicaid programs, especially in the delivery of mental health and substance abuse services (19). As outlined above, enrollees with severe mental or substance use disorders may face very different approaches to the provision of behavioral health services, depending on the state in which they reside.

The range of approaches to the provision of behavioral health services no doubt reflects the unique constraints within which each state must operate. These constraints may include everything from the needs of certain populations and the characteristics of the delivery system to budgetary issues and political pressures. A state-based approach in which each state Medicaid program functions as a "laboratory" for policy experimentation from which other states may learn certainly has its advantages in this regard. At the same time, however, this variation raises potential concerns about equity to the extent that certain approaches are associated with different levels of availability and quality of services and, by extension, different outcomes related to mental health and substance abuse conditions (20,21). Such heterogeneity thus raises both ethical concerns and the possibility of migration across state borders, which may in turn lead to a "race to the bottom" across state programs.

To date, neither the causal factors involved in the structural decisions outlined above nor the long-term implications of the resultant programmatic approaches have been investigated carefully and systematically. Such analysis would not only increase public understanding of the ways in which states design their Medicaid managed care programs but would also assist states that have yet to identify the approach to the delivery of behavioral health care services that works best for them (22). With this in mind, we emphasize that analyses are critically needed of the means by which state Medicaid managed care programs have arrived at their organizational approaches to the delivery of mental health and substance abuse services as well as of the specific implications of such approaches for populations in need of such services.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. The center was made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Medicaid Managed Care Program. The authors thank Julie Donohue, Deborah Garnick, Sc.D., Domenic Hodgkin, Ph.D., and Connie Horgan, Sc.D., for their comments and assistance in the preparation of this paper.

Ms. Hanson is a senior policy analyst at the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 1450 G Street, N.W., Suite 250, Washington, D.C. 20005, e-mail [email protected].Dr. Huskamp is assistant professor in the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., and Colette Croze, M.S.W., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Approaches to delivering behavioral health services to Medicaid beneficiaries in states with no capitated managed care organizations

|

Table 2. States using integrated and fee-for-service approaches to delivering behavioral health services in Medicaid managed care programs

|

Table 3. States using carve-out approaches to delivering behavioral health services in Medicaid managed care programs

1. National Summary of Medicaid Managed Care Programs and Enrollment. Washington, DC, Health Care Financing Administration, June 30, 1999Google Scholar

2. Hurley R, Freund D: A typology of Medicaid managed care. Medical Care 26:764-774, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Medicaid Managed Care for Persons With Disabilities: State Profiles. Report prepared for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Washington, DC, Economic and Social Research Institute, Dec 1998Google Scholar

4. Hurley RE, Draper DA: Medicaid managed care for special need populations: behavioral health as a "tracer condition." New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 78:51-65, 1998Google Scholar

5. Medicaid managed mental health care: is it a solution? Spotlight (Center for Vulnerable Populations) 1(1), 1993Google Scholar

6. Essock S, Goldman H: States' embrace of managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):34-44, 1995Google Scholar

7. Burns BJ, Teagle SE, Schwartz M, et al: Managed behavioral health care: a Medicaid carve-out for youth. Health Affairs 18(5):214-225, 1999Google Scholar

8. Dickey B, Normand SL, Norton EC, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945-952, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):51-64, 1995Google Scholar

10. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after a carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):40-52, 1998Google Scholar

11. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Costs and incentives in a behavioral health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

12. Aizer A, Gold M: Managed Care and Low-Income Populations With Special Needs: The Tennessee Experience. Report prepared for the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation and the Commonwealth Fund. Washington, DC, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc, May 1999Google Scholar

13. Beinecke R, Shepard D, Goodman M, et al: Assessment of the Massachusetts Medicaid managed behavioral health program: year three. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:205-219, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Itkin S, Cowie R: Finding the Right Fit: Managed Special Care in New York City. Report prepared for the United Hospital Fund and the New York Community Trust. New York, Coalition of Voluntary Mental Health Agencies and Legal Action Center, 1996Google Scholar

15. Egnew RC, Geary C, Wilson SN: Coordinating physical and behavioral healthcare services for Medicaid populations: issues and implications in integrated and carve-out systems. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 5(5):67-71, 1996Google Scholar

16. Chang C, Kaiser LJ, Bailey JE, et al: Tennessee's failed managed care program for mental health and substance abuse services. JAMA 279:864-869, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Medicaid Managed Care: Four States' Experiences With Mental Health Carveout Programs. GAO/HEHS-99-118. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, Sept 1999Google Scholar

18. Drainoni, ML, Tobias C, Dreyfus T: Medicaid Managed Care for People With Disabilities: Overview of the Population. Boston, Medicaid Working Group, 1995Google Scholar

19. Huskamp HA, Garnick DW, Hanson KW, et al: Medicaid managed care plan exit and enrollees with mental health and substance abuse conditions: assessing the implications of programmatic design, Psychiatric Services, in pressGoogle Scholar

20. Sparer MS, Brown LD: States and the health care crisis: the limits and lessons of laboratory federalism, in Health Policy, Federalism, and the American States. Edited by Rich RF, White WD. Washington, DC, Urban Institute Press, 1996Google Scholar

21. Fossett JW: Managed care and devolution, in Medicaid and Devolution: A View From the States. Edited by Thompson FJ, DiIulio JJ. Washington, DC, Brookings Institution Press, 1998Google Scholar

22. Gold M, Felt S: Reconciling practice and theory: challenges in monitoring Medicaid managed-care quality. Health Care Financing Review 16(4):85-105, 1995Google Scholar