Releasing Information to Families of Persons With Severe Mental Illness: A Survey of NAMI Members

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Guidelines for the treatment of severe mental illness recommend that providers share information with families and involve them in treatment. However, research indicates that consumer-provider-family collaboration is not part of routine clinical practice. This study examined the process of releasing information to families and the types of information they receive. METHODS: Self-administered surveys were completed by 219 family and consumer members of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. The surveys gathered information about their experiences with providers' releasing information. Consumers' attitudes toward collaboration and family members' satisfaction with providers were also measured. Regression analyses examined the relationship between consumers' attitudes toward family involvement and whether providers discussed family involvement or the release of information with consumers. Further analyses examined the relationship between family satisfaction and release of information. RESULTS: The majority of family respondents (72 percent) reported that they received some specific information about their relative's mental illness. Most families received information about diagnosis and medications, but few received information about the treatment plan. Few consumers reported that their permission was requested to release information to their families. Consumers' attitudes toward their family and toward family involvement were significantly associated with whether they were encouraged by their provider to involve a family member in their treatment. No significant relationship was found between consumers' attitudes and whether their provider discussed the release of information. Family members' satisfaction was positively related to whether they received information from providers. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that although some information is shared with families, collaboration is not currently part of routine clinical practice.

Clinical guidelines for the treatment of persons with severe mental illness recommend provider-consumer-family collaboration in all phases of the treatment process (1,2,3). In such collaboration, providers engage consumers and families in the process of treatment planning and share information with families about their relative's mental illness and treatment.

Recommendations encouraging collaboration were recently developed in response to evidence that sharing information with families reduces the frequency of relapse and thereby reduces rehospitalization for persons with severe mental illness (4,5,6). Families who receive information are able to support their ill relative more effectively (7,8,9,10,11,12). Information on the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of the relative's illness allows family members to assist their relative in monitoring symptoms and managing medication (13). Although evidence indicates that collaborative treatment benefits consumers by increasing treatment effectiveness, collaboration is not currently part of routine clinical practice (14,15).

Research indicates that attitudes may affect collaboration. Families who have been excluded from the treatment process may be skeptical of building collaborative relationships with providers. Families have reported encountering uncaring staff who leave them feeling frustrated and dissatisfied with the treatment process (16,17,18,19,20,21). When they have voiced their dissatisfaction to providers, the providers have misinterpreted their expressions as reflecting an unwillingness to become involved in their relative's treatment, thus creating a cyclical dynamic of noninvolvement.

Collaboration may also be influenced by consumers' attitudes toward family involvement. Providers may be less likely to discuss family involvement and less likely to ask for permission to release information to families of clients who express negative attitudes toward their family.

The lack of clarity about confidentiality policies on the release of information to families has also been discussed as a potential barrier to collaboration (13,16,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,,30). Confidentiality lies at the core of the therapeutic relationship. The therapeutic relationship is based on clients' trust that providers will not disclose information without their consent.

However, many mental health agencies do not have clear procedures for releasing information to families. In most states, providing even the most basic information about a client's condition or treatment without the client's consent is technically a breach of confidentiality statutes (personal communication, Ulan H, Sept 1998). Nonetheless, the consent forms in use in many mental health agencies may not be appropriate for obtaining consumers' authorization to release information to their families (25).

This study examined how mental health care providers discussed confidentiality with consumers and their families. The purpose of the study was to understand the types of information shared and the process by which information was released to families of persons with severe mental illness.

Methods

Sample

Self-administered surveys were distributed at the 1998 annual convention of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI). An additional mailing was sent to 50 NAMI state offices five months later. NAMI members distributed the surveys during support group and educational meetings and also included the survey in NAMI newsletters.

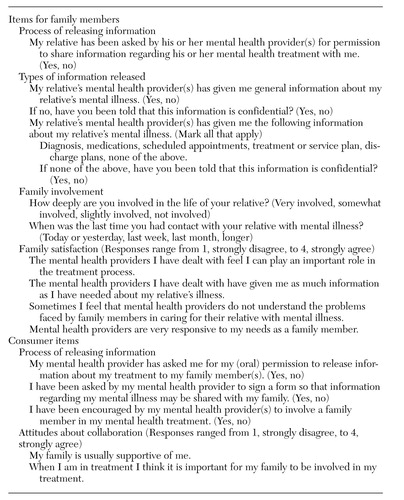

The survey was divided into three sections. Both consumers and family members completed the first section. The next two sections, shown in Table 1, included questions specifically for either consumers or family members. Respondents who were both consumers and family members were asked to complete all three sections. Data analyses were conducted with and without this subgroup, and no differences were found. For this reason, the subgroup was included in all data analyses.

Measures

Because of the lack of standardized instruments appropriate for this study, the survey items in Table 1 were developed by the authors. Items to which consumers responded measured the process of releasing information to families and consumers' attitudes toward collaboration. Items to which families responded measured the process for releasing information, the types of information released, and family involvement and satisfaction with providers.

Family satisfaction was measured using four items. Principal-components factor analysis indicated that the four items loaded as a single factor, which was interpreted as measuring family satisfaction with providers. The factor explained 56 percent of the variance. Therefore, responses to the four items were summed to create a satisfaction scale. The Cronbach's alpha for the satisfaction scale was .73.

Measures were pretested with ten families and five consumers. Frequency distributions for the measures indicated sufficient variability within the variables.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted using SPSS-PC software. Linear regression models were developed to test the hypothesis that when the analysis controlled for race, gender, education, and level of involvement with the ill relative, families who received general or specific information about their relative's mental illness were more likely to be satisfied with mental health providers. Logistic regression models were used to examine the association between consumers' attitudes toward family involvement and whether providers asked for written or oral permission to release information to their families or encouraged consumers to involve a family member in their treatment. Race, gender, and education were included as control variables. Missing data were handled through a process of pairwise deletion.

Results

Sample characteristics

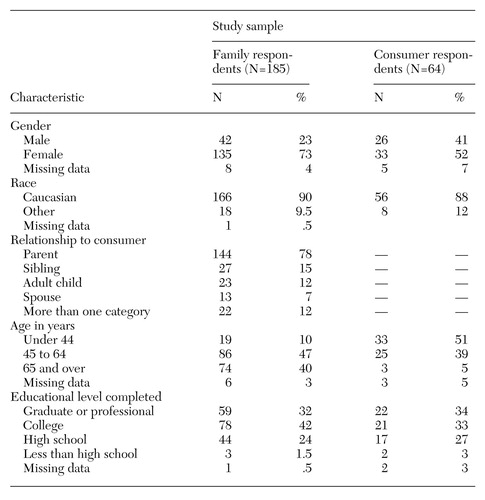

A total of 219 surveys were returned from 185 NAMI family members and 64 NAMI consumers; 30 respondents (14 percent) reported that they were both a family member and a consumer. Thirty states and the District of Columbia were represented in the sample. Most of the respondents were well educated; 90 respondents (41 percent) had finished college, and 72 (33 percent) had earned a graduate or professional degree. The majority of survey respondents were Caucasian (197 respondents, or 90 percent) and female (147 respondents, or 67 percent).

Most of the family respondents (144 respondents, or 78 percent) were parents of adults with severe mental illness. A total of 139 family respondents (75 percent) reported that they were very involved in their ill relative's life; 150 (81 percent) reported having contact with their relative within the past day.

Table 2 presents demographic characteristics of the consumer and family respondents. The sample was similar to the sample in a nationwide study of 1,401 NAMI members (31). In that study, most respondents were women, most were Caucasian (92 percent), and most were the parent of a person with mental illness (73 percent). In addition, a majority (70 percent) had completed college or graduate school.

Releasing information

Sixteen consumer respondents (25 percent) reported that providers asked for their written permission to disclose information to their family. Thirteen consumers (20 percent) reported that they were asked for their oral permission. Eighty-nine family respondents (48 percent) reported that their relative was asked by his or her mental health provider for permission to share information about treatment. Thirty-eight family respondents (21 percent) said their relative was not asked, and 20 (11 percent) were unsure.

Types of information families receive

A total of 109 family respondents (59 percent) indicated that they received general information from providers about their relative's mental illness. Of the 71 family respondents who did not receive general information, 48 (68 percent) were told that this information was confidential. Most family respondents (133 respondents, or 72 percent) received some specific information about their relative's mental illness. The majority of these respondents reported receiving information about their relative's diagnosis (110 respondents, or 83 percent) and medications (112 respondents, or 84 percent). Forty-three of the 133 family respondents who received information (32 percent) indicated that they received information about their relative's treatment or service plan. Thirty-five of the 52 family respondents who did not receive specific information (67 percent) were told that this information was confidential.

Consumers' attitudes toward collaboration

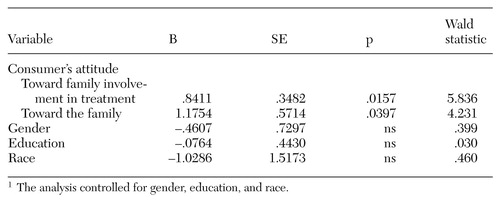

Fifty-one of the consumer respondents (80 percent) reported feeling supported by their family. Thirty-nine consumers (61 percent) reported that they thought it was important for their family to be involved in their treatment. However, only 23 consumers (36 percent) were encouraged by providers to involve a family member in their mental health treatment. A logistic regression model that controlled for race, gender, and education indicated that consumers' attitudes toward their family and toward family involvement were significantly associated with whether consumers were encouraged by their provider to involve a family member in their treatment (χ2=24.25, df=5, p=.001). Results of this model are summarized in Table 3.

No significant associations were found between consumers' attitudes toward their family and consumers' attitudes toward family involvement and whether providers asked consumers for their written or oral permission to release information to their family.

Family satisfaction

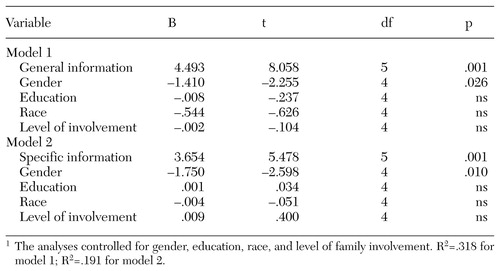

The results of the linear regression models shown in Table 4 indicated that families who received general or specific information about their relative's mental illness were significantly more likely to report that they were satisfied with mental health providers than those who did not receive information. Males were more likely than females to be satisfied with mental health providers.

Discussion and conclusions

The study was based on a nationwide sample of NAMI members. Like other samples of NAMI members (31), the study respondents were mostly parents of adults with mental illness, white, and well educated. Because NAMI is a support and education organization, NAMI members have more access to information about mental illness and are more likely to understand the mental health system. Consequently, NAMI members are significantly more likely to report contacts with professionals than are other family members (32). For these reasons, the study findings are not generalizable to all consumers and family members.

The sample was self-selected and the data were self-reported—two additional limitations of the study. The survey was anonymous, and thus it was not possible to determine whether consumer and family respondents were from the same family in order to assess discrepancies in the data. Future research would be strengthened by adding a provider sample and matching provider, family, and consumer responses.

Because of the exploratory nature of the study, the instrument was kept brief. Other variables that might be included in a more in-depth analysis of this issue are consumer diagnosis, severity of illness, and length of time since onset of the illness. Each of these variables may affect the process of releasing information to families.

What types of information are released?

The finding that the majority of family members in this study had received information about their ill relative's diagnosis and medications is encouraging and reflects progress toward more widespread provider-consumer-family collaboration. However, considering that the sample consisted of NAMI members, it is surprising that few families had received information about their ill relative's treatment plan. NAMI members have been shown to be significantly more likely than other families to have contact with their relatives' providers. One possible explanation for the finding is that information about diagnosis and medications may be shared with families at the time of the relative's intake into the mental health system; however, providers may not establish an ongoing collaborative relationship. Giving information about the treatment plan to families may require a deeper level of involvement between providers, consumers, and families.

These findings raise important questions about the current process of provider-consumer-family collaboration. At what point or points in the process do families typically receive information? Are there gender differences associated with the way that providers and families interact? Are mental health programs designed so that it is possible to include families in treatment planning? Are providers compensated (either reimbursed or allotted time) for collaborating with families? Further research is needed to explore these questions.

Who initiates the process?

Even though a large number of family respondents reported that they received some information from providers, many were not satisfied with their contact with providers. Unsolicited comments on the surveys suggested that the process of obtaining information was often initiated by consumers or family members and required much personal effort. In unsolicited comments, six respondents described the burden of having to learn the types of questions to ask in order to understand the mental health system and the treatment that their relative was receiving. Because information about most physical health problems may be released to a person's next of kin without his or her consent, consumers and families entering the mental health system are not likely to be aware of the need to initiate the release process to receive essential treatment information.

The following comments from a family respondent suggest that because a consumer's consent is needed to release information, families expect providers to initiate the release process. "My daughter was a patient at Hospital X three times in 1998. Twice when I inquired about her condition or asked to speak with her, I was told that I wasn't even supposed to know if my daughter was a patient. When a patient is interviewed on admittance, during the interview did anyone ask my daughter's permission to advise me, her mother, of her whereabouts? Whatever happened to common sense? Suppose, heaven forbid, something tragic had happened, then they would have told me—too late!"

Current treatment guidelines for severe mental illness recommend involving family members in all aspects of the treatment process. However, these findings suggest that even NAMI family members may be having a hard time becoming involved in their relative's treatment on an ongoing basis.

Whose decision is it to release information?

Even though the consumers in this study were affiliated with NAMI and reported a high degree of family support, few indicated that they were asked for permission to release information to their families. The data from family respondents supported the idea that many consumers are not asked for their permission before specific information about their illness is released to family members. These findings suggest that providers, consumers, and families are not working together as collaboratively as they could. The results also raise questions about how state statutes on confidentiality are interpreted by local agencies in regard to the release of information to families.

Variations within agencies may be promoting the perception among family members that providers hide behind a veil of confidentiality to avoid collaborating with family members (26,27,33). Although the majority of family respondents who did not receive specific information were correctly told that this information—diagnosis, medications, and the treatment or service plan—is confidential, most family respondents who did not receive general information about mental illness were told that general information was confidential. The findings suggest that confusion exists among providers, consumers, and families about the types of information that are confidential and those that are not.

Unsolicited comments received from 11 family respondents suggest that the release process may vary according to providers' interpretation of confidentiality policies. These family respondents reported that some providers released information to them while others did not. Some family members explained that their ill relative changed providers until he or she found a provider who allowed family involvement. Some of this variation in the release of information may be due to the absence of clear procedures and consent forms in many mental health systems (19).

Two hypotheses were tested to examine factors that may influence the process of collaboration and release of information to families. It was hypothesized that providers may be more likely to ask permission (oral or written) for releasing information to families from consumers who express more positive attitudes toward family collaboration. The results did not support this hypothesis. However, the findings showed that consumers' attitudes toward family involvement were positively associated with whether providers encouraged consumers to involve a family member in their treatment.

Research and practice implications

Research is needed to understand the current process used to release information to families, including how the process is initiated, how state statutes are interpreted, and how agency policies on confidentiality are implemented. The processes that are currently employed should be evaluated for their effectiveness in meeting the recommendations for provider-consumer-family collaboration that are outlined as best practices for the treatment of persons with severe mental illness.

Training for providers, consumers, and families is needed to clarify the types of information that are confidential and nonconfidential and the process for releasing confidential information. Training should emphasize that the choice to protect or release confidential information should be the consumer's decision and that collaborative treatment involves providers, consumers, and families working together.

Ms. Marshall is a doctoral candidate in the School of Social Work and a predoctoral fellow at the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research at the University of Pennsylvania, 3600 Market Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Solomon is professor in the School of Social Work at the university.

|

Table 1. Items from a survey on release of information by providers to family members conducted among members of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill

|

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of consumer and family members of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill who responded to a survey on release of information

|

Table 3. Results of a logistic regression examining the relationship between consumers' attitudes and whether their providers encouraged family involvement in treatment1

1 The analysis controlled for gender, education, and race

|

Table 4. Results of a logistic regression examining the relationship between family members' satisfaction with providers and whether they received general and specific information from providers about their ill relative1

1 The analyses controlled for gender, education, race, and level of family involvementR2=.318 for model 1; R2=.191 for model 2.

1. Dixon L, Lehman AF: Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631-643, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: Expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:1-58, 1996Google Scholar

3. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(Apr suppl):1-63, 1997Google Scholar

4. Anderson C, Reiss D, Hogarty G: Schizophrenia and the Family. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

5. Falloon I, Boyd J, McGill C: Family Care of Schizophrenia. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

6. Leff J, Kuipers L, Berkowitz R, et al: Controlled trial of social intervention in the families of schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 141:121-134, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Atkinson J: Schizophrenia at Home: A Guide to Helping the Family. New York, New York University Press, 1986Google Scholar

8. Bernheim K, Lehman A: Working With Families of the Mentally Ill. New York, Norton, 1985Google Scholar

9. Dearth N, Labenski B, Mott M, et al: Families Helping Families. New York, Norton, 1986Google Scholar

10. Dincin J, Selleck W, Steiker S: Restructuring parental attitudes: working with parents of the adult mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin 4:597-608, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hatfield A: Social support and family coping, in Families of the Mentally Ill: Coping and Adaptation. Edited by Hatfield A, Lefley H. New York, Guilford, 1987Google Scholar

12. Wasow M: Coping With Schizophrenia: A Survival Manual for Parents, Relatives, and Friends. Palo Alto, Science and Behavior Books, 1982Google Scholar

13. Petrilla JP, Sadoff RL: Confidentiality and the family as caregiver. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:136-139, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendation to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233-238, 1999Link, Google Scholar

16. Biegel DE, Song L, Milligan SE: A comparative analysis of family caregivers' perceived relationships with mental health professionals. Psychiatric Services 46:477-482, 1995Link, Google Scholar

17. Bernheim K: Psychologists and families of the severely mentally ill. American Psychologist 44:561-564, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Grella C, Grusky O: Families of the seriously mentally ill and their satisfaction with services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:831-835, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Hanson, J: Families' perceptions of psychiatric hospitalization of relatives with severe mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 22:531-541, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Holden D, Lewine R: How families evaluate mental health professionals, resources, and effects of illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:626-633, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Wright ER: The impact of organizational factors on mental health professionals' involvement with families. Psychiatric Services 48:921-927, 1997Link, Google Scholar

22. Zipple AM, Langle S, Spaniol L, et al: Client confidentiality and the family's need to know: strategies for resolving the conflict. Community Mental Health Journal 26:533-545, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Marsh DT, Magee RD: Ethical and Legal Issues in Professional Practice With Families. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

24. Biegel DE, Johnsen JA, Shafran R: Overcoming barriers faced by African-American families with a family member with mental illness. Family Relations 46:163-178, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Bogart T, Solomon P: Procedures to share treatment information among mental health providers, consumers, and families. Psychiatric Services 50:1321-1325, 1999Link, Google Scholar

26. Leazenby L: Confidentiality as a barrier to treatment. Psychiatric Services 48:1467-1468, 1997Link, Google Scholar

27. DiRienzo-Callahan C: Family caregivers and confidentiality. Psychiatric Services 49:244-245, 1998Link, Google Scholar

28. Marsh D: Confidentiality and the rights of families: resolving potential conflicts. Pennsylvania Psychologist, Jan 1995, pp 1-3Google Scholar

29. Furlong M, Leggatt M: Reconciling the patient's right to confidentiality and the family's need to know. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30:614-622, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Ryan J: Comment on reconciling the patient's right to confidentiality and the family's need to know. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30:429-430, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Leighninger RD, Speier AH, Mayeux D: How representative is NAMI? Demographic comparisons of a national NAMI sample with members and nonmembers of Louisiana mental health support groups. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:72-73, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Tessler RC, Gamache GM, Fisher GA: Patterns of contact of patients' families with mental health professionals and attitudes toward professionals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:929-935, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Epstein EL, Oram SE: Mental health records: the protective veil of confidentiality. Maine Bar Journal 11:162-166, 1996Google Scholar