The Nature of Help-Seeking During Psychiatric Emergency Service Visits by a Patient and an Accompanying Adult

Abstract

Utilization rates for urban psychiatric emergency services remain high, and the decision to seek care in this setting is poorly understood. Three hundred individuals accompanying patients to a psychiatric emergency service were interviewed about their help seeking and choice of treatment setting. Twenty-three of the interviewees (7.7 percent) were caregivers accompanying patients with severe and persistent mental illness. They were significantly more likely than other interviewees to know the difference between psychiatric emergency services and services offered by other outpatient providers. More than half reported that the patient they accompanied was intermittently noncompliant, which required visiting either a walk-in service during a moment when the patient was cooperative or a facility equipped to provide involuntary treatment.

In a society in which 50 to 75 percent of all individuals diagnosed as having mental illness live with family members (1), optimal care requires intentional structuring of treatment systems in ways that maximize benefits from their efforts to provide informal care. Previous research has characterized relationships between familial caregivers and individual treatment providers. However, given the decreasing availability of mental health services, information about these relationships may be less timely than information about familial relationships with local systems of care. Little research has attempted to describe the nature of help seeking by family members in relation to specific components of a community-based treatment system.

Studies indicate that 22 to 43 percent of psychiatric emergency room patients are accompanied by others (2,3). Data from the study by Rosenberg and Kesselman (3) imply that family members typically accompany unwilling or incapacitated patients. Gyllenhammar and associates (4) suggested that familial caregivers accompany patients to request rehospitalization when the caregiving burden becomes too great.

The generalizability of these findings has not been established. However, they illustrate the complex relationship between patient, care provider, and system of care. Additional work is needed to identify service expectations and utilization patterns among informal care providers. This study was designed to collect preliminary data about the nature of help seeking represented by patient-companion dyads visiting a psychiatric emergency service. It sought to characterize these dyads and describe the role of the help-seeking companion, the decision to seek care, and the selection of the psychiatric emergency service as the treatment facility.

Methods

Interviewees were 300 persons accompanying patients to the psychiatric emergency service of an urban public teaching hospital that has an average of 10,000 visits a year and treats patients for up to 23 hours. Additional characteristics of the study site and population have been described elsewhere (5). Interviewees were a sample presenting between 11 am and 11 pm Monday through Saturday in the summer of 1995. All spoke English, were 17 years of age or older, accompanied a patient over 17 years of age, and provided informed consent. They were classified as primary care providers or as noncaregiver companions by self-report. The study was approved by the hospital's institutional review board.

The semistructured interview used for this study included the Dysfunctional Behavior Rating Instrument (6) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Rating Scale (7). Information was also obtained about the type of help sought, such as hospitalization and medications, the reasons for accompanying the patient, and the reasons for selection of the psychiatric emergency service as treatment provider.

It was hypothesized that persons accompanying patients with more extensive treatment histories would have different help-seeking patterns than less experienced help seekers. Therefore, patients with severe and persistent mental illness were identified using 1988 criteria from the National Institute of Mental Health: a diagnosis of psychotic disorder or severe character disorder, illness duration of two years or more, and functional disability. Functional disability criteria included current moderate behavioral dysfunction, which was measured as a score of 30 or higher on the Dysfunctional Behavior Rating Instrument; mild impairment in activities of daily living, which was measured as a score of 19 or higher on the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Rating Scale or current homelessness; and moderate impairment in performance at work, which was measured as current joblessness.

For some analyses, self-identified caregivers of persons with severe and persistent mental illness were compared with all other interviewees, which included noncaregiver companions of persons with severe mental illness and caregivers and companions of persons without severe mental illness.

Demographic information— age, race, and sex— and clinical information, such as voluntary or involuntary admission status and DSM-IV diagnosis, was obtained from medical records. Symptom onset was defined as recent when it was within 72 hours of coming to the emergency service. The degree of observable behavioral problems in the psychiatric emergency service— continuous, intermittent, or absent— was rated in keeping with Murdach's emergency illness episode criteria (8).

Level of care is a local billing code designating the intensity of treatment in the psychiatric emergency service. In this analyses, level I represents intense care, in which medical interventions such as laboratory testing or medications were used or when seclusion lasted more than eight hours; level II represents minor care, in which such measures were absent or lasted less than eight hours. Disposition was categorized as hospitalized or not.

To determine whether the results from the patient-companion dyads included in the study were generalizable, chi square analysis and t tests were used to compare these visits with those of other dyads not included in the study. Interview results were then tallied, and responses from caregivers accompanying patients with severe and persistent mental illness were compared with responses of other interviewees to identify ways in which previous help-seeking experience influenced utilization patterns.

Results

Generalizability

During the summer of 1995, a total of 2,143 adult visits to the psychiatric emergency service were documented, and a family member or friend was present for at least part of 1,029 visits (48.2 percent). To help establish generalizability of interview results, the 300 patient visits included in the study were compared with the remaining 729 accompanied patient visits on all patient demographic and visit variables.

No significant differences were found on most major variables. However, the study group included significantly more patients with previous psychiatric treatment (χ2=111.09, df= 1, p=.001), an intense level of care during the current visit (χ2=9.61, df=1, p=.002), a need for hospitalization (χ2=16.27, df=1, p=.001), and no recent suicide attempt (χ2=16.60, df=1, p=.001). Thus interview responses appeared somewhat weighted toward dyads representing patients with recurring mental difficulties who were in the midst of a serious illness episode that did not include a suicide attempt.

Interviewees

Analyses were conducted to understand who came with the patient and why. Among the 300 interviewees, most were female (191 persons, or 63.7 percent) and first-degree relatives of the patient they accompanied (219 persons, or 73 percent). More than half (165 persons, or 55 percent) resided with the patient, and only 42 (14 percent) reported that the patient had experienced a recent onset of symptoms. Among the 258 interviewees who stated that they delayed help seeking, the most frequently stated reasons were a hope that the problem might self-correct (63 persons, or 24.4 percent) and a perception that the patient was unwilling to seek treatment (50 persons, or 19.4 percent).

Most interviewees (239 persons, or 79.7 percent) reported that a "triggering" event such as dysfunctional patient behavior ultimately prompted their seeking help. For 245 interviewees (81.7 percent), the decision to accompany the patient involved a belief that the patient was either incapable of or unwilling to go to the emergency service alone. A total of 155 interviewees (51.7 percent) verbalized a wish for the patient to be hospitalized.

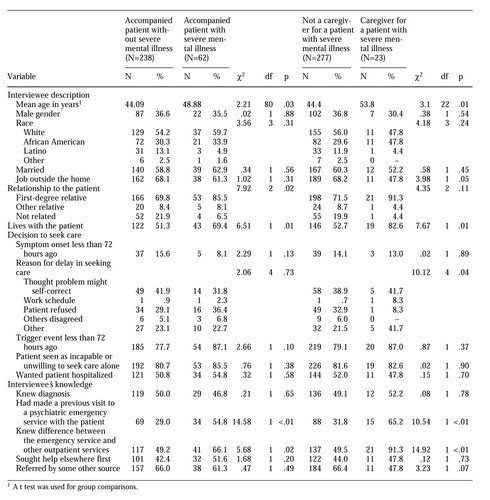

Table 1 presents comparisons between caregivers accompanying persons with severe and persistent mental illness (N=23) and all other caregivers and companions (N=277). Caregivers of persons with severe mental illness tended to be older than other interviewees. Fewer worked outside the home, and more lived with the accompanied patient. Significantly more caregivers of persons with severe mental illness had previously visited the psychiatric emergency service and could identify a unique feature of treatment in this setting.

Nine of the 23 caregivers of persons with severe mental illness said that before coming to the emergency service they had waited for a moment of cooperation from the patient, who was unaware or not accepting of the need for treatment during an episode of serious illness. Four of the 23 caregivers stated that when the acutely ill patient remained steadfastly noncompliant, they delayed seeking help until legal conditions for involuntary treatment, as defined by state mental health law, were likely to be met. In both instances of delaying treatment, the psychiatric emergency service represented the only 24-hour, walk-in service provider available.

Discussion

Results from analyses of the interviews appear to support different patterns of use of the psychiatric emergency service according to features of the help-seeking dyad. Overrepresentation of some groups in the interview pool does not appear to have obscured these differences. Half of the interviewees who were not caregivers of persons with severe mental illness were unable to differentiate unique features of treatment in the emergency setting. Despite the close relationship between most interviewees and the patient they accompanied, some interviewees may not have been involved enough to accurately reflect the patient's care-seeking efforts. However, other patients' visits to the emergency service appear to be the result of fairly uninformed service use.

Given the differences between the psychiatric emergency service and other providers, indiscriminate use of the emergency service may have an adverse impact on the success of the help-seeking effort (9). A triage and referral function built into the emergency service intake process with seamless transitions to other community-based systems (10) might go a long way toward promoting more effective service use.

Data from this study further imply that families providing care to intermittently noncompliant individuals with severe and persistent mental illness have specific service needs. Clinicians report that burnout among caregiving families is frequently associated with significantly reduced quality of life for patients with severe mental illness. It is in the best interests of patients, care providers, and treatment systems, therefore, to find ways to address these service needs directly, and the psychiatric emergency service may be able to play a pivotal role in augmenting such efforts.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by Mental Health Connections, a partnership between Dallas County Mental Health-Mental Retardation and the department of psychiatry of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Funding was from the Texas state legislature and the Dallas County Hospital District. The research was also partly supported by grants MH-41115 and MH-53799 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Martin Lumpkin, Ph.D., and Tom Carmody, Ph.D., for technical support and Kenneth Z. Altshuler, M.D., and Maurice Korman, Ph.D., for administrative support.

The authors are affiliated with the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, Texas 75235-9070 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Claassen and Dr. McIntire are assistant professors, Dr. Hughes is professor, and Dr. Roose and Dr. Basco are clinical assistant professors in the division of clinical psychology. Dr. Gilfillan is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and interview responses of 300 persons accompanying patients to a psychiatric emergency service, by whether they accompanied a person with or without severe and persistent mental illness and whether they were a caregiver for a person with severe and persistent mental illness

1. Johnson DL: The family's experience of living with mental illness, in Families as Allies in Treatment of the Mentally Ill: New Directions for Mental Health Professionals. Edited by Lefley HP. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

2. Dhossche DM, Ghani SO: Who brings patients to the psychiatric emergency room? Psychosocial and psychiatric correlates. General Hospital Psychiatry 20:235-240, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Rosenburg RC, Kesselman M: The therapeutic alliance and the psychiatric emergency room. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:78-80, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Gyllenhammar C, Lundin T, Otto U, et al: The panorama of psychiatric emergencies in three different parts of Sweden. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 237:61-64, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Claassen CA, Hughes CW, Gilfillan S, et al: Toward a redefinition of psychiatric emergency. Health Services Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

6. Malloy DW, Bedard M, Buyatt GH, et al: Dysfunctional Behavior Rating Instrument. International Psychogeriatrics 8(suppl 3):333-341, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lawton MP, Brody EM: Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9:179-186, 1969Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Murdach AD: Decision making in psychiatric emergencies. Health and Social Work 12:267-274, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Solomon P, Beck S: Patient's perceived needs when seen in a psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Quarterly 60:215-226, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Ries R: Advantages of separating the triage function from the psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Services 48:755-756, 1997Link, Google Scholar