Pathways to Housing: Supported Housing for Street-Dwelling Homeless Individuals With Psychiatric Disabilities

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the effectiveness of the Pathways to Housing supported housing program over a five-year period. Unlike most housing programs that offer services in a linear, step-by-step continuum, the Pathways program in New York City provides immediate access to independent scatter-site apartments for individuals with psychiatric disabilities who are homeless and living on the street. Support services are provided by a team that uses a modified assertive community treatment model. METHODS: Housing tenure for the Pathways sample of 242 individuals housed between January 1993 and September 1997 was compared with tenure for a citywide sample of 1,600 persons who were housed through a linear residential treatment approach during the same period. Survival analyses examined housing tenure and controlled for differences in client characteristics before program entry. RESULTS: After five years, 88 percent of the program's tenants remained housed, whereas only 47 percent of the residents in the city's residential treatment system remained housed. When the analysis controlled for the effects of client characteristics, it showed that the supported housing program achieved better housing tenure than did the comparison group. CONCLUSIONS: The Pathways supported housing program provides a model for effectively housing individuals who are homeless and living on the streets. The program's housing retention rate over a five-year period challenges many widely held clinical assumptions about the relationship between the symptoms and the functional ability of an individual. Clients with severe psychiatric disabilities and addictions are capable of obtaining and maintaining independent housing when provided with the opportunity and necessary supports.

Homeless individuals who have psychiatric disabilities and concurrent substance addictions constitute an extremely vulnerable population. The vulnerability is particularly evident among persons who are living on the streets, carrying their bundled belongings, sitting in transportation terminals, and huddled in doorways or other public spaces. These individuals face distressing consequences, including acute and chronic physical health problems, exacerbation of ongoing psychiatric symptoms, alcohol and drug use, and a higher likelihood of victimization and incarceration (1,2,3). Members of this segment of the homeless population do not consistently use services but sporadically appear in drop-in centers, soup kitchens, and psychiatric and medical emergency rooms (4). They are the least likely subgroup of the homeless population to gain access to housing programs.

As with other parts of the homeless population in America, it is difficult to ascertain the number of persons who are literally homeless. Over a five-year period in the late 1980s, 3.3 percent of New York City residents had used the public shelter system (5). Estimates of the number of people on the streets of New York City range from 10,000 to 15,000 (6). The prevalence of mental illness among all sectors of the homeless population ranges from 20 to 33 percent (7,8); however, it is estimated to be considerably higher among the street-dwelling population (9,10).

Most studies ascribe homelessness to personal and clinical characteristics, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, psychiatric disability, and substance abuse (4,11,12). These studies cite the same factors when discussing the ability to obtain and retain housing. Other observers argue that larger social, political, and economic factors, such as lack of affordable housing, increase or decrease the number of people who remain homeless (13,14,15).

Service providers describe enormous difficulties in engaging homeless mentally ill persons who are living on the streets (16). Interventions in use today range from persuasion through a prolonged period of outreach (17) to involuntary transportation to a psychiatric hospital (18). Some researchers argue that individuals in this segment of the population reject services because they distrust and are frustrated with the fragmented mental health, drug treatment, and medical care systems, which are unable to coordinate services to meet their needs, especially the need for housing (1,19).

Survey studies have shown that homeless consumers have different perceptions of their service needs than do providers. Consumers believe that meeting basic needs should come first, whereas providers emphasize mental health services (20,21). Several studies found that consumer self-determination predicts whether or not an individual will accept services (19,22). Other evidence suggests that many individuals who are labeled uncooperative by providers are willing to accept help if they view that help as relevant to them (23). Despite such consistent findings, mental health programs, especially those involving housing, have not been characterized by consumer-driven service approaches.

The linear residential treatment model

The design of New York City's service system for individuals who are homeless and mentally ill is consistent with the recommendations of the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness (24). The system consists of several program components, which as a whole form a linear continuum of care. The system is designed to assist clients through a step-by-step progression of services that begins with outreach, includes treatment, and ends with permanent housing (25).

In the first step, outreach programs engage the individual who is literally homeless and encourage him or her to accept a referral to low-demand second-step programs, such as drop-in centers, shelters, safe havens, or other transitional settings. These programs allow the person to remain indoors, usually for a specified period of time. They also provide assistance in obtaining entitlements and psychiatric or substance abuse treatment. These second-step programs are aimed at developing clients' housing readiness so that they will be able to meet eligibility criteria required by housing providers. Complying with psychiatric treatment and maintaining periods of sobriety are frequently among such criteria.

Finding permanent housing is the third and final point on the continuum. Most providers use the linear residential treatment model to operate permanent housing programs. The programs consist of a wide assortment of congregate living facilities, such as group homes, community residences, and single-room-occupancy residences, with varying intensities of on-site services. The end point of this continuum is independent housing where the client can live in the community with few, if any, supports. The model combines treatment and housing under one program in an effort to match clients to the treatment residence best suited to their needs and capacities. Residents are placed in a variety of congregate living options with varying degrees of supervision.

In linear residential treatment programs, clinical status is closely related to housing status. To be admitted to the program, a client must agree to participate in psychiatric and substance abuse treatment. If he or she subsequently has a psychiatric crisis or relapses into drug abuse, the clinical team may move the client into a more intensely supervised housing setting. The programs also require clients to participate in ongoing psychiatric treatment and to maintain sobriety if they are to retain their housing. The overall goal of these programs is to stabilize clients and prepare them for independent living.

Consumers and advocates have identified several flaws in the linear residential treatment model. One serious problem is the lack of consumer choice and freedom in treatment or housing. Another is the stress that results from congregate living and frequent change of residence. A third problem is inferred from research on psychiatric rehabilitation that indicates that skills learned for successful functioning at one type of residential setting are not necessarily transferable to other living situations (26). A fourth problem is that it takes a substantial amount of time for clients to reach the final step on the continuum. Finally, the most important problem with the model is that individuals who are homeless are denied housing because placement is contingent on accepting treatment first (27).

The Pathways supported housing program

Pathways to Housing, a nonprofit agency in New York City, developed a supported housing program to meet the housing and service needs of homeless individuals who live on the streets and who have severe psychiatric disabilities and concurrent addiction disorders. The program is designed for individuals who are unable or unwilling to obtain housing through linear residential treatment programs. Founded on the belief that housing is a basic human right for all individuals, regardless of disability, the program provides clients with housing first—before other services are offered. All clients are offered immediate access to permanent independent apartments of their own.

Clients enter the program directly through outreach efforts of staff of the Pathways supported housing program or through referrals from the city's outreach teams, drop-in centers, or shelters. Priority is given to women and elderly persons, who are at greater risk of victimization and health problems (28), and to individuals with other risk factors, such as a history of incarceration, that impede access to other programs.

When clients are admitted, the staff assists them with locating and selecting an apartment, executing the lease, furnishing the apartment, and moving in. Tenants select the location of their own apartments from available units on the open market. They decide whether anyone will live with them and who those roommates will be. Most apartments are owned and leased to clients individually by private landlords. If a suitable apartment is not found immediately, clients who are living on the streets are provided with a room at the local YMCA or a hotel until an apartment is secured.

The apartments are scatter-site studio, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom units in affordable locations throughout the city's low-income neighborhoods. The program subsidizes approximately 70 percent, and sometimes more, of tenants' rents through grants from city, state, and federal governments and section 8 vouchers.

Honoring consumer preference is at the heart of the supported housing program's clinical services. Mental health, physical health, substance abuse, vocational, and other services are provided in vivo by program staff using an assertive community treatment team format. The teams are modeled after the original Madison assertive community treatment program (29) and modified to include the agency's consumer preference philosophy. In keeping with the original model, the teams' major goals are to reduce or eliminate the patient role, meet basic needs, enhance quality of life, increase social skills and social roles, and increase employment opportunities (30). The assertive community treatment teams operate in a manner that makes such teams effective for individuals with a dual diagnosis (31,32).

Unlike the traditional assertive community treatment model, the Pathways supported housing program allows clients to determine the type and intensity of services or refuse them entirely. Other departures from the traditional assertive community treatment model include the practice of radical acceptance of the consumer's point of view, use of a harm-reduction approach to drug use, and a staffing pattern of full-time employees, about half of whom are consumers. Harm reduction is a useful practice for this dually diagnosed population for two reasons. The harm-reduction approach does not require abstinence, and thus housing can be obtained even if abstinence remains an unmet goal. The approach also means that relapse does not result in loss of housing, and it creates opportunities to celebrate small gains toward complete control over substance use. Harm reduction also promotes the reduction of other harmful behaviors associated with substance abuse. Having consumers as staff allows them to make many valuable contributions, including providing a model of recovery for both clients and staff. In summary, every effort is made to provide all interventions in an atmosphere that is accepting, respectful, and compassionate and that fosters a mutual striving for creative solutions to life's challenges.

The supported housing program has two requirements: clients are asked to meet with staff a minimum of twice a month and to participate in a money management plan. These requirements are applied flexibly to all tenants. For example, housing or services would not be denied to a person coming off the streets after many years who feels mistrustful about agreeing to money management.

Comparison of programs

Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of clinicians have expressed doubts about the feasibility of supported housing in general (33), let alone a program offering immediate access to supported housing to individuals who are literally homeless. These clinicians argue that supported housing is, at best, suitable for a small, high-functioning group (34). Most service providers favor the linear residential treatment model that uses clinically managed residential treatment settings and that regards homeless mentally ill persons as too fragile and too clinically unstable to cope with "normal" life (35,36,37,38).

Proponents of the supported housing model regard consumer choice rather than treatment compliance as the necessary first step in the recovery process. Recent research findings support this view. In one study, clients who were given a choice among housing options reported greater housing satisfaction, improved housing stability, and greater psychological well-being (39). Consumer preference studies have found that the lack of consumer choice can actually accelerate homelessness, because consumers may choose the relative independence of the streets to the restrictions of a highly structured residential facility (40).

Several studies have found that many of the liberties taken for granted by most Americans—privacy, control over one's daily activities, and choice about living alone or with others—are also ideas valued greatly by individuals with psychiatric disabilities (41,42,43). Furthermore, consumers regard their housing problems as more strongly related to economic and social factors than to psychiatric disability. They report that lack of income, rather than psychiatric disability, is the main barrier to securing stable housing (14,41,44,45,46).

The growing body of research and survey literature favoring the supported housing model, together with the limited effectiveness of traditional housing approaches based on the linear residential treatment model, has led to what some have described as a paradigm shift toward a new housing model (47,48). This shift entails a movement away from residential treatment guided by therapeutic principles to supported housing models guided by consumer preference (49,50). Despite state and national policy shifts favoring the new paradigm, the implementation of supported housing programs has been relatively slow because it entails dramatic changes in program philosophy and practice (48). As a consequence, the Pathways supported housing program is one of the few models available to advocates of supported housing.

Little empirical evidence directly compares supported housing and residential treatment programs. This study examined the issue of program effectiveness. It attempted to answer two major questions. First, can homeless individuals who live on the streets and who have psychiatric disabilities or substance addictions successfully obtain and maintain an independent apartment of their own without prior treatment? And second, do housing programs that require clients to participate in psychiatric treatment and maintain sobriety have a greater housing retention rate than a program that first offers clients access to independent living without requiring treatment?

Methods

The housing retention rate of the Pathways supported housing program was compared with rates of other New York City agencies operating linear residential treatment programs for the city's homeless mentally ill population. The comparison sample was provided through the city's Human Resources Administration, the agency that monitors housing programs for the homeless mentally ill. The Human Resources Administration collects data from a citywide consortium of approximately 65 housing providers, working together under the auspices of the New York-New York Agreement (51) to house the homeless mentally ill; most use the linear residential treatment approach to housing.

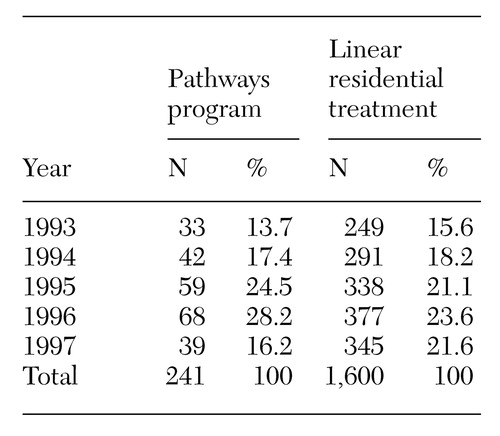

At the time the Human Resources Administration was contacted to provide data for this study, information was available on individuals placed through September 1997. Because Pathways was initiated in late 1992, individuals placed between 1993 and September 1997 were included in the analysis. As can be seen in Table 1, clients entered the two programs at comparable rates over the five-year period.

The Pathways sample consisted of the 241 clients who were housed at some point during the period from January 1, 1993, to September 30, 1997. A total of 4,102 clients were housed through the New York-New York Agreement program during the same period. As the majority of Pathways clients are referred from the streets (42 percent), drop-in centers (24 percent), and shelters (18 percent), only clients referred to New York-New York housing from outreach teams, drop-in centers, shelters, and reception centers were included in the housing tenure analysis. This approach was taken to reduce differences between samples. It resulted in a sample of 1,600 clients, or 39 percent of the total New York New-York sample.

The largest segment of the New York-New York sample, 55 percent, was initially placed in supportive single-room-occupancy hotels; 35 percent were placed in community residences, and the remaining 10 percent were placed in several other settings. Only eight of the 1,600 New York- New York clients (.5 percent), went directly into scatter-site apartments. The entire Pathways sample went directly into independent scatter-site apartments.

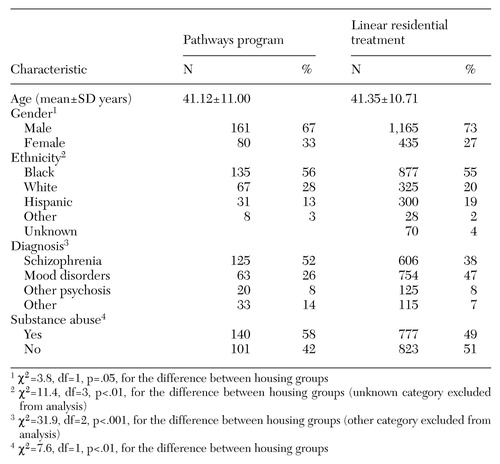

Table 2 lists the characteristics of the two samples, including age, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis, and substance abuse. The two samples differed significantly on all variables except age. Compared with the New York-New York sample, the Pathways sample had a greater proportion of women (33 percent versus 27 percent) and individuals with a substance abuse diagnosis (58 percent versus 49 percent). Also, the Pathways sample had a greater percentage of individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia (52 percent versus 38 percent) and a smaller percentage of clients with a mood disorder diagnosis (26 percent versus 47 percent). The Pathways sample had a greater percentage of white clients (28 percent versus 20 percent) and a smaller percentage of Hispanic clients (13 percent versus 19 percent).

Survival analyses were used to examine tenure in housing. First, the survival variable, the number of days continuously housed from January 1993 through September 1997, was computed for each individual in the study. Those who remained housed were classified as "continuous." Individuals who became homeless or moved into unstable housing situations during this period were considered "discontinuous." A "failure" occurred when a person had a discontinuous placement. Individuals who left housing for long-term placements, such as nursing homes, were considered to be "censored."

Results

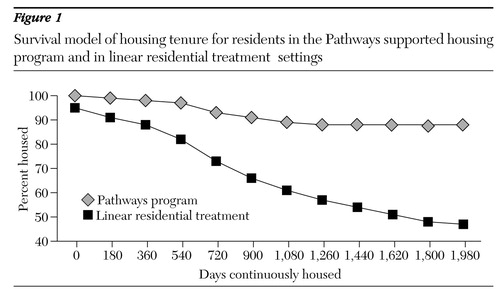

Because the participants entered housing at different points during the study period, the Kaplan-Meier product-limit survival method for progressively censored data was used (52). Survival functions for the two samples are reported in Figure 1. Individuals from the Pathways group were more likely than those from the linear residential treatment sample to remain housed for up to four and a half years. After five years, 88 percent of those in the Pathways program and 47 percent of those in the comparison group remained housed.

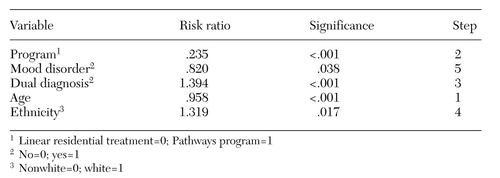

To control for the effects of client characteristics that may have contributed to this housing tenure outcome, a forward stepwise Cox regression survival model was used (52). In this procedure, variables are selected into the equation in order of importance in predicting survival time. This procedure also provides risk ratios for all variables selected, adjusting for all other variables in the equation. Risk ratios greater than one indicate an increased risk, and ratios less than one a decreased risk.

Table 3 shows the results for those variables that significantly predict tenure in housing. Of the variables considered, type of program was the second most important predictor of housing tenure. Being older or having a mood disorder increased tenure in housing, whereas having a dual diagnosis and being white decreased housing tenure. Moreover, the results indicated that the tenants of the Pathways program achieved greater housing tenure than those in the linear residential treatment settings when the analysis controlled for the effects of the other client variables in the equation. Specifically, the risk of discontinuous housing was approximately four times greater for a person in the linear residential treatment sample than for a person in the Pathways program.

Dual diagnosis has been shown to reduce housing retention significantly (53,54). Therefore, additional analyses were conducted to examine the retention rates of individuals with a dual diagnosis. Results of a forward stepwise Cox regression survival analysis, stratified for dual diagnosis, showed that the same variables, with the exception of mood disorder, were selected into the equation as in the initial analysis (Table 3). Survival plots revealed that dual diagnosis reduced housing tenure in both programs. However, the dually diagnosed tenants in the Pathways program maintained a higher housing rate than those in the comparison sample.

Further analyses included the interaction variables of gender by group, ethnicity by group, and dual diagnosis by group. None of the interaction variables were selected into the equation, which suggests that gender, ethnicity, and dual diagnosis operated similarly in both housing groups.

Discussion

The 88 percent housing retention rate for the Pathways supported housing program over a five-year period, together with the much lower risk of homelessness for Pathways residents than for linear residential treatment residents, supports a new model for effectively housing individuals who are homeless and living on the streets. The Pathways model blends elements of supported housing with assertive community treatment in a manner that effectively engages individuals who are homeless and have remained beyond the reach of traditional approaches. Supported housing offers the independence and privacy that most consumers desire. Most other programs, in contrast, offer supported housing as the last step on the continuum with minimal clinical support. Using assertive community treatment as the clinical component, supported housing can effectively house and keep housed individuals with a dual diagnosis who enter the program directly from the streets.

The housing retention results emphasize the importance of program models. Of the several variables considered, type of program was the second most important predictor of housing retention, more predictive than either diagnosis or substance abuse. These findings support the assumption that housing program characteristics are more important than most personal or clinical variables in accounting for housing retention. Findings are also consistent with research from psychiatric rehabilitation, which indicate that if the goal is for the individuals to live independently in the community, the optimal setting to learn the necessary skills is the community. For the homeless clients in these programs, living in apartments of their own with assistance from a supportive and available clinical staff teaches them the skills and provides them with the necessary support to continue to live successfully in the community.

These findings also challenge the widely held assumption that a strong relationship exists between psychopathology and the ability to maintain housing. The Pathways program effectively serves clients with severe psychiatric disabilities and substance addictions. Clients often labeled by other programs "not housing ready" or "treatment resistant" are capable of choosing, obtaining, and maintaining independent housing when participating in the Pathways program.

Furthermore, after clients are housed and away from the war zone of life on the streets, they are much more likely to seek treatment for mental health problems and substance abuse voluntarily. Clients have reported that having an apartment of their own, sometimes for the first time, gives them something that they want to hold on to. More than 65 percent of the Pathways tenants in the sample were receiving treatment from the program's psychiatrist. Another index of the effectiveness of self-motivation is that 27 percent of the tenants in the program were employed at least part of the time during the 1997 calendar year.

Dually diagnosed clients are at greater risk for housing loss in the Pathways program, just as they are in all other housing programs. The harm reduction approach employed by the program ensures that all possible measures are taken to help the individual move from high to low drug use and from high-risk to low-risk behaviors (55). The program will also use any means possible to reduce the risk of eviction that often results from drug use. The methods include strict money management, relocation to another neighborhood, or a contract to hold the apartment if the client seeks treatment. The practice of harm reduction challenges staff to maintain a consumer-driven stance while working with a tenant whose drug use is out of control. A basic premise of all clinical interventions is that the program will have a long-term—lifelong if necessary—commitment to every client.

Conclusions

The supported housing program described here represents a significant paradigm shift from the linear residential treatment model. Although few would argue that residential treatment settings have no place in the new paradigm, the Pathways program challenges popular clinical assumptions about the limitations of people with severe mental illness and the type of housing and support that is best suited to meet their needs.

Pathways to Housing was recently awarded a two-year homelessness prevention grant from the Substance Abuse Services and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to conduct a longitudinal study comparing tenants who have been randomly assigned to the Pathways program or to linear residential treatment settings. The SAMHSA study, a collaboration with eight other cities, will provide additional data on program outcomes, such as psychiatric symptoms, drug and alcohol use, social networks, and housing satisfaction. However, the findings reported here highlight the importance of consumer choice in operating effective housing and treatment programs.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was partly funded by grant 1UD9SM51970 from the SAMHSA Center for Mental Health Services. The authors thank Frank Lipton, M.D., for permission to use the New York-New York data, Carole Siegel, Ph.D., for statistical advice, Cheryl Baker, Ph.D., for statistical analysis, and Kim Hopper, Ph.D., and Deborah Padgett, Ph.D., for their comments.

Dr. Tsemberis is executive director of Pathways to Housing, Inc., 155 West 23rd Street, 12th Floor, New York, New York 10011 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Eisenberg is affiliated with the department of psychology at New York University.

Figure 1. Survival model of housing tenure for residents in the Pathways supported housing program and in linear residential treatment settings

|

Table 1. Placement by year of clients in the Pathways supported housing program and in New York City linear residential treatment settings

|

Table 2. Characteristics of clients in the Pathways supported housing program and in linear residential treatment settings housed between January 1, 1993, and September 30, 1997

|

Table 3. Cox stepwise regression surviaval models of variables predicting tenure in housing for residents in linear residential treatment settings and in the Pathways supported housing program

1. Osher FC, Drake RE: Reversing a history of unmet needs: approaches to care for persons with co-occurring addictive and mental disorders. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:4-11, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Wright JD: Poor people, poor health: the health status of the homeless. Journal of Social Issues 46:49-64, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Barr H: Prisons and Jails: Hospitals of Last Resort. New York, Correctional Association of New York and the Urban Justice Center, 1999Google Scholar

4. Barrow SM, Hellman F, Lovell AM, et al: Evaluating outreach services: lessons from a study of five programs. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 52:29-45, 1991Google Scholar

5. Culhane D, Dejowski EF, Ibanez J, et al: Public shelter admission rates in Philadelphia and New York City: the implications of turnover for shelter population counts. Housing Policy Debate 52:107-140, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Christian NM: The forecast: a battle to survive. New York Times, Oct 20, 1998, p B1Google Scholar

7. Koegel P, Burnam MA, Baumohl J: The causes of homelessness, in Homelessness in America. Edited by Baumohl J. Phoenix, Ariz, Oryx, 1996Google Scholar

8. Robertson M: The prevalence of mental disorder among homeless people, in Homelessness: A Prevention-Oriented Approach. Edited by Jahiel R. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992Google Scholar

9. Shern DL, Lovell AM, Tsemberis S, et al: The New York City street outreach project serving a hard-to-reach population, in Making a Difference: Interim Status Report of the McKinney Demonstration Program for Homeless Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1994Google Scholar

10. Tsemberis SJ, Cohen NL, Jones RM: Conducting emergency psychiatric evaluations on the street, in Intensive Treatment of the Homeless Mentally Ill. Edited by Katz SE, Nardacci D, Sabatini A. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

11. Drake RE, Wallach MA, Hoffman JS: Housing instability and homelessness among aftercare patients of an urban state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:46-51, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Blankertz LE, Cnaan RA: Principles of care for dually diagnosed homeless persons: findings from a demonstration project. Research on Social Work Practice 2:448-464, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Baumohl J (ed): Homelessness in America. Phoenix, Ariz, Oryx, 1996Google Scholar

14. Cohen CI, Thompson KS: Homeless mentally ill or mentally ill homeless? American Journal of Psychiatry 169:816-823, 1992Google Scholar

15. Shinn M, Gillespie C: The roles of housing and poverty in the origins of homelessness. American Behavioral Scientist 37:505-521, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Making a Difference: Interim Status Report of the McKinney Demonstration Program for Homeless Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1994Google Scholar

17. Lopez M: The perils of outreach work: overreaching the limits of persuasive tactics, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis DL, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

18. Cohen NL, Marcos LR: Psychiatric care of the homeless mentally ill. Psychiatric Annals 16:729-732, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Asmussen S, Romano J, Beatty P, et al: Old answers for today's problems: helping integrate individuals who are homeless with mental illnesses into existing community-based programs. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 17:17-34, 1994Google Scholar

20. Dattalo P: Widening the range of services for the homeless mentally ill. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 17:247-256, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Martin MA: The homeless mentally ill and community-based care: changing a mindset. Community Mental Health Journal 26:435-447, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Martin MA, Nayowith SA: Creating community: groupwork to develop social support networks with homeless mentally ill. Social Work With Groups 11:79-93, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Shern DL, Tsemberis S, Winarski J, et al: A psychiatric rehabilitation demonstration for individuals who are street dwelling and seriously disabled, in Mentally Ill and Homeless: Special Programs for Special Needs. Edited by Breakey WR, Thompson JW. Baltimore, Harwood, 1997Google Scholar

24. Outcasts on Main Street: Report of the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness. DHHS pub ADM 92-1904. Washington, DC, Interagency Council on the Homeless, 1992Google Scholar

25. 1997 Homeless Programs. Washington, DC, US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1997Google Scholar

26. Anthony WA, Blanch A: Research on community support services: what have we learned? Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 12:55-81, 1989Google Scholar

27. Korman H, Engster D, Milstein B: Housing as a tool of coercion, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

28. Padgett D, Struening E: Influence of substance abuse and mental disorders on emergency room use by homeless adults. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:834-838, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

29. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Allness DJ: The Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT): the model and its replication. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 74:17-26, 1997Google Scholar

31. Drake RE, McHugo, GJ, Clark RE, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201-215, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216-232, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Lamb H, Lamb D: Factors contributing to homelessness among the chronically and severely mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:301-305, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

34. Hatfield A: A family perspective on supported housing. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:496-497, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

35. Pepper B: Where (and how) should young adult chronic patients live? The concept of a residential spectrum. TIE-Lines 2:1-6, 1985Google Scholar

36. Bebout RR, Harris M: In search of pumpkin shells: residential programming for the homeless mentally ill, in Treating the Homeless Mentally Ill: A Report of the Task Force on the Homeless Mentally Ill. Edited by Lamb HR, Bachrach LL, Kass FI. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

37. Rosenson M: Supported housing. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:891, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

38. Fields S: The relationship between residential treatment and supported housing in a community system of services. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13:105-113, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Livingston JA, Srebnik D, King DA: Approaches to providing housing and flexible supports for people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:27-43, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Howie the Harp: Independent living with support services: the goals and future for mental health consumers. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13:85-89, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Tanzman B: An overview of surveys on mental health consumers' preferences for housing and support services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:450-455, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

42. Owen C, Rutherford V, Jones M, et al: Housing accommodation preferences of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 47:628-632, 1996Link, Google Scholar

43. Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM: Housing preferences and perceptions among homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 47:381-386, 1996Link, Google Scholar

44. Brown MA, Ridgway P, Anthony WA: Comparison of outcomes for clients seeking and assigned to supported housing services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1150-1153, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

45. Carling PJ: Return to Community: Building Support Systems for People With Psychiatric Disabilities. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

46. Goldfinger SM: The Boston project: promoting housing stability and consumer empowerment, in Center for Mental Health Services: Making a Difference: Interim Status Report of the McKinney Demonstration Program for Homeless Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1994Google Scholar

47. Ridgway P, Zipple AM: The paradigm shift in residential services: from the linear continuum to supported housing approaches. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13:20-31, 1990Google Scholar

48. Carling PJ: Housing and supports for persons with mental illness: emerging approaches to research and practice. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:439-449, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

49. Howie the Harp: Taking a new approach to independent living. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:413, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

50. Goering P, Durbin J, Trainor J, et al: Developing housing for the homeless. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13:33-42, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

51. Lipton FR: The New York-New York Agreement to House Homeless Mentally Ill Individuals Summary Placement Report. New York, Human Resources Administration Office of Health and Mental Health Services, Mar 1998Google Scholar

52. Lee ET: Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis. New York, Wiley, 1992Google Scholar

53. Hurlburt MS, Hough RL, Wood PA: Effects of substance abuse on housing stability of homeless mentally ill persons in supported housing. Psychiatric Services 47:731-736, 1996Link, Google Scholar

54. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Tolomiczenko GS, et al: Housing placement and subsequent days homeless among formerly homeless adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:674-679, 1999Link, Google Scholar

55. Marlatt G, Tapert SF: Harm reduction: reducing the risks of addictive behaviors, in Addictive Behaviors Across the Life Span. Edited by Baer JS, Marlatt GA, McMahon RJ. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar