Using Quality Improvement Teams to Improve Documentation in Records at a Community Mental Health Center

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A community mental health center sought a system for qualitative review of patients' records to improve the quality of documentation through the engagement of clinical staff in the review process. METHODS: The center developed a quality improvement system in which treatment team clinicians use a scored 30-item protocol to measure the quality of record documentation by peers. Questions address whether the record documents the full range of the psychiatric treatment process, including assessment and diagnosis, treatment planning, and provision of clinical services. Other questions address specific contractual or regulatory requirements, such as whether procedure codes are correct, and evaluate the physician's record of medication management. Each treatment team at the mental health center's six clinics has a quality improvement work group, composed of the team psychiatrist and at least one other team clinician. Each month the work group meets to review two randomly selected medical records from another treatment team at the same clinic and arrive at a consensus score. An administrative oversight team meets regularly with clinician-reviewers to foster uniform scoring of the protocol throughout the center. RESULTS: An analysis of the trend in protocol scores over a 21-month period suggests that the procedure improves the quality of the documentation in patients' records. CONCLUSIONS: A team-based quality review process appears to have a positive impact on the quality of medical record documentation. Improved documentation may improve continuity of care and improve the accuracy of record information used for other quality measurement systems.

Administrators at community mental health centers are increasingly accountable for both the cost-efficiency and the quality of care provided in their centers. Quality of care, in particular, can be difficult to monitor, especially in the management of chronic disorders such as those treated in community outpatient clinics (1).

Many outcome measures suitable for acute treatments have less relevance in chronic care. It is not surprising, therefore, that few approaches have been described to monitor the quality of care in outpatient mental health settings (2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Information about approaches to measuring quality is more readily available in general medicine (9,10,11,12).

The long-standing issue of the quality of medical record documentation becomes more important in light of the increasing focus on measures of efficiency and outcome. Stakeholders turn to medical record documentation for the data required for measuring many outcomes. Better record keeping may provide more accurate data for quality measurement systems.

This report describes a system for improving the quality and accuracy of documentation in patients' records in an outpatient community mental health center. The system uses a continuous quality improvement framework and measures medical record content by guided peer review. The system is unique in that it combines team-based monitoring with administrative oversight, thereby ensuring that quality standards are met but also fostering clinicians' ownership of the quality improvement process.

Methods

Setting

The review process developed out of a quality improvement consultation to a community mental health center in a large Southwestern city, beginning in 1995. The center is funded by a mix of county, state, and federal grants-in-aid and Medicaid and Medicare funding streams, with virtually no managed care contracts.

The center's adult mental health services are provided by six outpatient clinics throughout its metropolitan catchment area. The clinics are a component of an adult mental health division within the center. Each clinic has from three to six multidisciplinary treatment teams, composed of a psychiatrist and five other clinicians. Each team cares for about 300 patients. Virtually all patients have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. The case mix varies little from team to team. About a third of the patients come to the clinics from acute care hospitals. The remainder are self-referred.

Assessment instrument

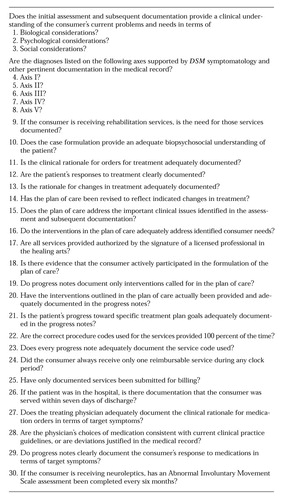

The medical records review process uses a protocol in a format similar to the one presented by Rago and Gilbert (13). Although the review has both quantitative and qualitative components, the primary goal is to assess the overall quality of the documentation of services in the medical record. The protocol is shown in Table 1.

The first 18 questions attempt to evaluate the full range of the psychiatric treatment process, including assessment and diagnosis, treatment planning, and provision of clinical services. Five questions about the presence of multiaxial diagnoses require specific data coupled with clinical judgment. The second part of the protocol, questions 19 through 26, deals with specific contractual or regulatory requirements for reimbursement or funding. The final four questions evaluate the physician's record of medication management. Most questions require clinical judgments about the adequacy of documentation, although a few, particularly those related to regulatory compliance, are quantitative.

Reviewers assign yes or no ratings to each of the questions. A personal judgment is made about whether the quality of the documentation covered by a particular item passes or fails. The reviewer must decide whether the specific circumstances and needs of the patient are adequately addressed and documented.

A yes rating can mean that the quality of the documentation ranges from excellent to marginal. An item may be judged inadequate if the team makes a significant error in assessment of the patient, misses a clinically important intervention, or does not adequately document services provided or decision-making processes. A score for the entire medical record is calculated as the percentage of questions rated yes. A score of 70 percent is considered passing. In practice, a passing record is legible, contains logical entries from multiple team members, and reflects average to above-average quality of care.

Quality improvement work groups

Each treatment team has a quality improvement work group, composed of the team psychiatrist and at least one other team clinician, assigned on a rotating basis. In all, 24 such work groups meet monthly for two hours each. Each group reviews two medical records from another treatment team at the clinic, thus allowing about one hour for each review. Records to be reviewed are randomly selected by the clinic's quality assurance monitor.

Work group members first review the two charts independently. Then the work group discusses differences in individual scoring, a critical component of the review. Disagreements are noted and discussed, and a consensus is reached. A consensus protocol is completed and reported to that clinic's quality improvement team.

The quality improvement team

The quality improvement team for the clinic meets monthly to review the protocols obtained from all of that clinic's work groups during the month. Its members include the clinic's medical director, administrator, quality assurance monitor, and various other clinicians who rotate on and off the team. Considering the information and scores provided by the work groups, the team develops plans of improvement for individual records and for individual clinicians.

The team also identifies local, systemic issues affecting the quality of care and documentation to be addressed by the clinic's leadership. Larger systemic issues requiring action by the center's administration are also identified. All of these findings are reported monthly to the adult mental health division's medical director.

Division oversight team

A divisionwide oversight team visits the six clinics on a rotating basis, so that each clinic usually is visited quarterly. The oversight team is composed of the division medical director, the division administrative director, the director of nursing, a senior clinical psychologist, and a professor of psychiatry from a regional medical center who serves as a consultant under contract to the center. In addition, various members of the six clinic quality improvement teams rotate through the division oversight team.

During each site visit, the oversight team rereviews two charts that had previously been reviewed by the treatment team work groups, using the same protocol format for its reviews. The members review the records individually, and then a consensus is obtained through discussion. Team members have a surprisingly high level of agreement, with generally fewer than five protocol questions eliciting any disagreement at all. Most disagreements stem from one reviewer's missing data in the chart. The other, less frequent reason for disagreement is a difference in the standard for judging an item.

After the oversight team completes consensus protocols, it meets with the entire clinical staff and administrative leadership of the site for a question-by-question comparison between the scores determined by the oversight team and the treatment team work group. Overall scores are compared as well. This process is used to calibrate the scores assigned at the work group level to the standards set by the division leadership.

The oversight team attempts to conduct these meetings with the spirit of continuous quality improvement, rather than of seeking to punish by publicly decrying documentation or care that is deemed inadequate. Clinicians are encouraged to talk publicly about issues affecting quality and to work together to devise ways to enhance quality. The emphasis is on improving future documentation once clinicians are armed with a new understanding of documentation problems.

Evaluating performance

Assessment of each clinic's performance is accomplished by calculating a mean score for two records reviewed by that site's work groups and by the division oversight team for the month. A performance target for the mean is established (70 percent). The clinic passes the evaluation process if the mean score for the two charts scored by the oversight team is above this target, and if the mean score given to the two charts by the local work group is within 8 percentage points of the mean score given by the oversight team.

Results

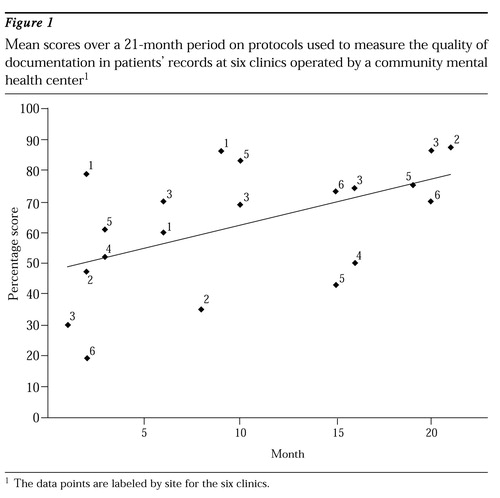

Figure 1 shows the trend in protocol scores assigned by the oversight team over a 21-month period, from January 1997 to September 1998. Each data point on the chart represents the mean score of one visit to one of the six clinics. Each point is labeled to show the site scored. The figure shows an upward trend in scores over the period (r2=.27, p=.02). This finding suggests that although documentation in earlier reviews did not meet division standards, later reviews reflected an improvement in documentation.

Discussion

Consultation to the center suggested that a culture change was required if a review process was to be successful. The process required a strong mandate by the center's administrative and clinical leadership. Ongoing support was required so that clinical staff became and remained comfortable with taking the time to complete the medical records reviews and with critically evaluating the care provided by their peers. This support was required so that staff could see the process as more than another intrusion by management.

Using a team-based model facilitates three levels of group process and team building. In every work group meeting, a discussion about factors important to quality documentation weaves through the consensus-building section of the protocol completion. A similar group process must occur within each clinic's quality improvement team. In practice, we have seen these teams develop into strong working groups that develop ideas for enhancing not only quality of documentation but also quality of care within the clinics. This approach has led to clear changes, including improved legibility of medical records, more comprehensive formulations, and more meaningful treatment planning.

The culture in the center now allows clinical teams to become more active in making recommendations to administrative leadership to improve quality. These recommendations have led to modifications in division procedures, priorities, and resource allocations. For example, a physician work group recommended that the center implement a physician progress note, with prompts to ensure documentation to protocol standards. Also, many of the clinic teams have initiated ongoing training in writing formulations and treatment plans, leading to clinician-generated recommendations for changes in the treatment-planning process and medical records forms.

Conclusions

Although the method described here is a useful step toward enhancing the quality of medical records, it still has significant limitations. The record sample size for the entire division is approximately 12 percent annually, certainly not large enough to ensure quality. This limitation in the review is due to the time-intensive nature of the review process. Methods that allow a more time-limited, qualitative review are needed.

The subjective nature of the reviews is also a limitation. The lack of blinding of raters or a control group limits the generalizability of the findings. Also, although the data presented here show a trend toward improved documentation, the process nonetheless is very subjective. For example, it is possible that biases about the efficacy of the process may have led the division oversight team to inflate scores at later reviews. However, the changing membership of the group and the use of a multiple convergent rating approach to scoring likely minimized this possibility. In addition, no data exist on the reliability of the procedure in assessing the actual quality of care. Methods that standardize reviews without becoming merely technical audits would improve the review process.

The process of chart review described here consumes a considerable amount of clinician time and is therefore fairly expensive. Undertaking this process is an ethical choice that the center made in how to allocate its financial and clinical resources. In the context of diminishing resources, the focus on clinicians' ownership of quality may actually have the effect of enhancing morale and even productivity. Clearly, a process that focuses on medical record documentation represents an initial step in an overall quality improvement program, part of an ongoing effort that also would include measurements of outcome, as well as measures of the performance of individual clinicians (14).

These limitations notwithstanding, the process presented here provides a means to review documentation and care in a systematic and qualitative way. It allows for true peer review of documentation. It is also a method that may involve all caretakers in the review process, thereby facilitating their ownership of quality care.

When this report was prepared, Dr. Baker was medical director for adult mental health with the Mental Health-Mental Retardation Authority of Harris County in Houston, where Dr. Schnee is executive director. Dr. Baker is currently medical director for Magellan Behavioral Health of Texas, 1349 Empire Central Drive, Suite 600, Dallas, Texas 75247 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Shanfield is professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio.

Figure 1. Mean scores over a 21-month period on protocols used to measure the quality of documentation in patients' records at six clinics operated by a community mental health center1

1The data points are labeled by site for six clinics

|

Table 1. A protocol for monitoring documentation in patients' records at a community mental health center

1. Smith G, Fischer E, Nordquist C, et al: Implementing outcomes management systems in mental health settings. Psychiatric Services 48:364-368, 1997Link, Google Scholar

2. Dickerson F: Assessing clinical outcomes: the community functioning of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:897-902, 1997Link, Google Scholar

3. Srebink D, Hendryx M, Stevenson J, et al: Development of outcome indicators for monitoring the quality of public mental health care. Psychiatric Services 48:903-909, 1997Link, Google Scholar

4. Keller G: Management for quality: continuous quality improvement to increase access to outpatient mental health services. Psychiatric Services 48:821-825, 1997Link, Google Scholar

5. Kurland D: A review of quality evaluation systems for mental health services. American Journal of Medical Quality 10:141-148, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lavender A, Leiper R, Pilling S, et al: Quality assurance in mental health: the QUARTZ system. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 33:451-467, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Plapp J, Rey J: Child and adolescent psychiatric services: case audit and patient satisfaction. Journal of Quality in Clinical Practice 14:51-56, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

8. Rosenheck R, Cicchetti D: A mental health program report card: a multidimensional approach to performance monitoring in public sector programs. Community Mental Health Journal 34:85-106, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Whipple T, Little A: Variance analysis for care path outcomes management. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 12:20-25, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. McGlynn E, Asch S: Developing a clinical performance measure. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14:14-21, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Oxman A, Thomson M, Davis D, et al: No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. Canadian Medical Association Journal 153:1423-1431, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

12. Donaldson M, Nolan K: Measuring the quality of health care: state of the art. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 23:283-292, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rago W, Gilbert D: TQM as resolution to a major class-action lawsuit. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 22:48-57, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Baker J: A performance indicator spreadsheet for physicians in community mental health centers. Psychiatric Services 49:1293-1298, 1998Link, Google Scholar