Best Practices: Treating High-Cost Users of Behavioral Health Services in a Health Maintenance Organization

The management and delivery of mental health services by health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are undergoing increased scrutiny by purchasers and consumers alike. Published reports have stated that mental health services are a poor stepchild to medical services in virtually all insurance arrangements, including HMOs (1).

Controversy has arisen because HMOs generally allocate between 3 and 5 percent of expenditures for behavioral health services, while nationally such services account for about 10 percent of total costs (2). HMOs have been criticized for attempting to control mental health care costs by applying managed care techniques such as higher copayments and deductibles, aggressive utilization review, and outright termination of mental health benefits (1). Additional scrutiny is being given to HMOs as increasing numbers of Medicaid clients and individuals with serious mental illness are enrolling in prepaid health plans (3,4). The marketplace has seen increasing attention paid to integrating and coordinating mental health with general medical care, and health maintenance organizations have been at the forefront of this trend (5).

As the face of the behavioral health care industry changes, the delivery systems of care within it are also changing. Although HMOs need to be cost competitive, they are also faced with increasing demands for patient satisfaction (1). The proliferation of private, for-profit managed behavioral health care companies poses a major competitive threat to HMOs, forcing some to improve their behavioral health care benefit. In northern California, Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program, a large nonprofit health maintenance organization, invested $100 million over a five-year period to upgrade its behavioral health care. Kaiser in southern California is making similar improvements to ensure a continuum of care for its members (6).

This paper describes the use of a modified assertive community treatment team in an HMO environment. Assertive community treatment services have been used extensively in public mental health settings, but the best-practices approach described here indicates that this community-based model of treatment can also be effective within the structure of an HMO.

Kaiser-Telecare collaboration

Durham (1) has called on HMOs to examine the essentials of their mental health care delivery system. She states that rather than adhering strictly to policy exclusions and limits, HMOs should enhance service delivery by using population-based care management and experimenting with financial incentives that reward improvements in mental health status (1). In early 1997 Kaiser Permanente Medical Group of Southern California approached the Telecare Corporation about providing assertive community treatment (ACT) services to Kaiser members who used the highest percentage of acute inpatient psychiatric services. The Kaiser administration's major goals were to expand the continuum of care for members, offer a community-based service to frequent users of emergency psychiatric care, and reduce acute inpatient costs. Telecare is a privately held, for-profit organization that specializes in providing a full continuum of mental health services, including ACT services, to individuals with serious mental illness.

The Kaiser behavioral health care benefit plan includes locked acute inpatient services, 23-hour observation and assessment beds, intensive outpatient care, individual and group therapy, partial hospitalization, and crisis residential services. For individuals with substance use disorders, sober-living residential services, detoxification, education classes, and outpatient services are provided. ACT services were not available, and the Kaiser administration made a decision to contract for these services, rather than provide them directly.

Kaiser and Telecare formulated a contractual agreement that reimburses Telecare on a fee-for-service basis for providing services to an identified population of individuals with intermittent recidivism in the use of high-end acute services and individuals with co-existing mental illness and substance use disorders who used a disproportionate share of resources. It was acknowledged that these populations were not mutually exclusive and that some clients would fall into more than one category.

Service model

After a comprehensive clinical review of the identified client population, it was mutually agreed that a modified ACT team would be used. Telecare would operate the program for intensive community support and provide team services directed at decreasing inpatient hospital use and increasing client functioning and satisfaction. The team would consist of one team leader, one registered nurse, and two mental health rehabilitation specialists.

The history and efficacy of the ACT model has been thoroughly described (7,8). The Telecare model of community support is known as intensive community support services and is characterized by the following essential elements:

• Comprehensive, continuous service delivery to persons who are high users of the most costly mental health services

• Prevention of unnecessary hospitalization and assistance to individuals with basic community survival skills to improve the quality of their lives

• Improvement of access to natural resources, such as families, friends, spiritual supports, self-help groups, and other community resources

• Support and education to families and significant others

• Intervention to prevent the emergence of crises and manage unavoidable crises outside the hospital

• Advocacy on clients' behalf in their efforts to negotiate troublesome system obstacles

• Provision of services face to face in the homes or communities where clients live.

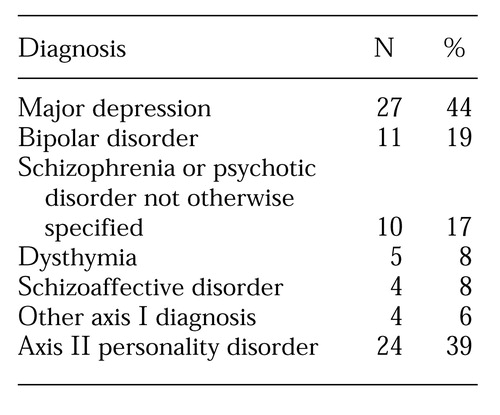

Efforts to measure program fidelity to the ACT model have been well documented (9). The ACT model adopted in this partnership was modified due to clinical and structural variables. In most mental health settings, ACT teams serve individuals with serious mental illness, few social supports, and high use of acute and emergency psychiatric services. The target population served in this project had a lower incidence of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder than in most populations served by ACT teams. Diagnoses of the first 61 individuals served are listed in Table 1. It was also found that this cohort also had significantly more social supports than populations normally served by ACT teams. Forty-one (67 percent) had a coexisting mental illness and substance use disorder and were unable to successfully make use of the Kaiser behavioral health care system.

Another tenet of the ACT model and intensive community support services is a multidisciplinary team approach using a psychiatrist, nurses, social workers, and other support staff. Kaiser wished to continue the use of the Kaiser staff psychiatrists and therapists, with Telecare providing psychiatric rehabilitation, skills training, and community support. A major goal of the Telecare team is to help members use existing Kaiser treatment services more appropriately.

For these reasons, three major adaptations were made in the ACT model. The first involved clients' length of tenure in the program. ACT programs are normally designed for individuals who may require lifetime support due to the seriousness of their mental illness. The majority of individuals targeted by Kaiser for the program have significant social supports and rely less on the team to meet their basic needs. No limit is placed on length of tenure, but if clients meet treatment goals, they can be discharged within 90 days.

A second adaptation was related to enrollment and disenrollment. Clients are enrolled in the program on an ongoing basis not to exceed 45 enrolled individuals at any one time. Clients are disenrolled as their needs dictate, or when they no longer need this level of intervention. Third, the Telecare team consists of three professional rehabilitation specialists and one registered nurse. Program clients receive their psychiatric care from Kaiser physicians. The staffing ratio of one team member for every 11 clients is slightly higher than that in traditional ACT programs, which is normally one to ten.

Best-practice program elements

Since its implementation in 1998, this program has had an opportunity to create interventions that were not previously available to members of HMOs. Four of the best-practice program elements are described below.

Intensity and range of services

On average, the program provides 14 hours a month of direct services to each member. Some clients receive as many as 30 hours of services a month. The services provided by the team are an adjunct to the continuing services they receive from their regular Kaiser treatment provider. Telecare staff have received considerable feedback from members that they are pleasantly surprised by the amount of assistance they receive. Several members initially expressed gratitude that their activities with staff were not limited to the "50-minute hour." Members have also said that they appreciate the variety of activities they experience with staff, such as going to the movies or amusement parks, meeting for lunch or dinner, or having staff attend family functions.

Dual diagnosis services

Due to the high prevalence of dual diagnoses among the target population, staff have provided a number of interventions directed at managing co-occurring disorders. Staff use the substance abuse treatment model of the Program for Assertive Community Treatment (10), which employs a multistage treatment structure.

Although sobriety is the long-range goal, relapse is expected. The team works closely with clients to identify replacement behaviors. Because the model emphasizes a long-term approach, program staff continue to work with clients even when they are actively using substances. It appears that clients with co-existing mental health and substance use disorders require longer-term interventions, more consistent with the ACT model's principle of continuous, ongoing treatment.

Close collaboration with Kaiser staff

Telecare staff work closely with the Kaiser staff members who provide clinical treatment services to clients. Telecare staff make every effort to engage clients to make optimal use of their available behavioral health care benefits. A particularly close working relationship exists between Telecare staff and the psychiatrists who manage acute inpatient services.

Round-the-clock availability of the team

Instituting an on-call procedure in which program clients in a crisis can contact Telecare staff at any time of the day or night has greatly reduced the need for acute inpatient admission. The inpatient psychiatrists have noted that this improvement is one factor responsible for a decrease in the number of admissions.

Outcomes

A major objective of the contractual agreement between Telecare and Kaiser was to reduce utilization of acute inpatient services. Clients were eligible for the program based on their use of inpatient services for the previous two years. Pre-enrollment assessments were completed for all clients, and Telecare staff asked the clients to sign consent forms for treatment. The clients identified by Kaiser as candidates for the program were more easily located than clients in Telecare's public-sector programs.

Besides the goal of reducing inpatient utilization, Kaiser and Telecare instituted a battery of clinical and quality improvement outcome measures to evaluate community functioning, client satisfaction, substance use, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores, and use of other behavioral health care services.

The Telecare program staff administer the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (11) to measure client functioning. The scale has 17 items and measures positive and negative change in the areas of interference with functioning, adjustment to living, social competence, and behavioral problems. Of the first 31 clients to whom the instrument was administered at two time points at least 90 days apart, the majority exhibited improvements in all 17 areas. The greatest gain occurred in the area of behavioral problems, which addresses issues of cooperation with medication regimens and treatment providers, abuse of drugs and alcohol, and frequency of extreme acting out. Nineteen of the 31 clients (61 percent) exhibited gains in these four areas.

The Behavioral Healthcare Rating of Satisfaction (12) is used to measure clients' satisfaction with the services of the Telecare team. The instrument is administered at discharge. Of the first 36 clients discharged from the program, 34 (94 percent) expressed general satisfaction with the program and a positive attitude toward staff. Thirty-five (97 percent) gave positive responses to a question about whether the services focused on their needs, while 34 responded positively to a question about whether the program helped improve the quality of their life.

It appears that implementation of the ACT team also resulted in a decrease in clients' use of other Kaiser behavioral health care services. After the first six months, a decrease was noted in the use of crisis residential facilities, chemical dependency inpatient days, 23-hour emergency beds, and electroconvulsive therapy. The sole service that showed a slight increase in utilization was residential recovery homes, as these services were used by the team to stabilize clients in the community in a sober-living environment

The majority of the clients of the program showed improvements in GAF scores after the first six months. Of the first 35 program members, 23 (66 percent) had an average increase of 14 points, indicating better functioning. Seven (20 percent) had an average decrease of nine points, while for five clients (14 percent), GAF scores did not change.

For the first 45 clients in the program, the total number of inpatient days in the two years before program entry was 1,242. After the first nine months of the program, 57 clients were enrolled in the program. For the total population of clients enrolled, a 75 percent reduction in inpatient days was noted.

It is clear that this program has resulted in a dramatic reduction in the use of inpatient services. Given this reduction and the decrease in use of most other behavioral health care services, it appears that the approach described here is cost-effective for the HMO. Further research is needed to test this model in a controlled study with a comparison group.

Lessons learned

The provision of modified ACT services to members of HMOs is a novel concept. Previously, ACT services were seen as being more suitable for clients in the public mental health sector. With the increasing enrollment of Medicaid patients in health maintenance organizations, the diagnostic profiles of behavioral health care users in HMOs are beginning to mirror those of public-sector programs for individuals with serious mental illness.

ACT programs, such as the modified type used in the Kaiser-Telecare partnership, can fill a critical need in the continuum of services of HMOs. A small but significant percentage of individuals appears to require behavioral health care services beyond the typical constellation found in HMOs. Once these individuals are identified, they seem to benefit from this approach. Further research is planned to determine the effect of the program on all other associated behavioral health care costs, community functioning, and client satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Steve Wilson, M.D., Patricia Bathurst, M.S., and Marcia Kagnoff, Ed.D., for their contributions.

Mr. Quinlivan is the director of managed care services and the Kaiser-Telecare program for intensive community support for the Telecare Corporation, 3211 Jefferson Street, San Diego, California 92110 (e-mail, [email protected]). William M. Glazer, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Primary axis I and axis II diagnoses of 61 clients ina program providing assertive commuinty treatment in a health maintenance organization

1. Durham ML: Can HMOs manage the mental health benefit? Health Affairs 14(3):116-122, 1995Google Scholar

2. Christianson JB, Osher FC: Health mainte-nance organizations, health care reform, and persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 45:898-905, 1994Link, Google Scholar

3. McFarland BH, Johnson RE, Hornbrook MC: Enrollment duration, service use, and costs of care for severely mentally ill members of a health maintenance organization. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:938-944, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Riggs RT: HMOs and the seriously mentally ill: a view from the trenches. Community Mental Health Journal 32:213-222, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mechanic D: Approaches for coordinating primary and specialty care for persons with mental illness. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:395-402, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Iglehart JK: Managed care and mental health. New England Journal of Medicine 334:131-135, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Drake RE: Brief history, current status, and future place of assertive community treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:172-174, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Mueser KT, Bond G, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of the research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37-74, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216-232, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Allness DJ, Knoedler WH: The PACT Model of Community-Based Treatment for Persons With Severe and Persistent Mental Illnesses: A Manual for PACT Start-Up. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1998Google Scholar

11. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al: A community ability scale for chronically mentally iss consumers: part I. reliability and validity. Community Mental Health Journal 30:363-383, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Dow MG: The Florida outcome evaluations system for public mental health and substance abuse providers. Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Health Servcies Research, Chicago, June 27-29, 1999Google Scholar