Therapists' Contacts With Family Members of Persons With Severe Mental Illness in a Community Treatment Program

Abstract

Thirty-six therapists at an urban community mental health center responded to a survey about contacts with family members of 214 clients with serious mental illness. For 61 percent of the clients, the therapists reported at least one past-year contact with a family member or someone acting as a family member. Contacts were typically by telephone and often took place during crises. The focus was on problem solving rather than on providing family therapy. Therapists perceived significant benefit from the contacts, which were achieved with little effort on their part. The results suggest that informal—and perhaps nonbillable—brief services to families are common. Such informal services fall short of recommended best-practice standards.

Involved family members of people with serious mental illnesses often provide considerable support and assistance to their ill relatives and experience considerable stresses (1,2,3,4). Family members can be important allies for both consumers and providers of mental health services, and they often desire support from and information exchange with clinicians.

Treatment recommendations of the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) and other recent standards of care maintain that outreach, education, and support for family members of clients should be part of best practices. Yet the extent to which mental health programs actually strive to meet the needs of family members has not been documented (5,6).

The most detailed data available are rudimentary and not encouraging. Most mental health programs do not track their rates or types of family contacts, and states do not require such monitoring for funding (7). The PORT found that only .7 percent of persons whose diagnosis of schizophrenia was reported on a paid Medicare claim in 1991 had any paid claim for family therapy (8). A similar sample of patients with Medicaid claims in 1991 showed that only 6.9 percent of patients had a paid claim for family therapy (7).

In a PORT interview survey of persons with schizophrenia, 31 percent of 539 clients who maintained contacts with their families reported that their families had received some kind of "information about my illness or treatment or advice or support for families about how to be helpful to me." In addition, a recent evaluation of quality of care at two public mental health clinics included a measure of family contacts (9). The sole benchmark for "poor-quality family management" was "no evidence … that staff had met with or spoken to a family member during the past year." Even by this minimal measure, staff had recorded no contact with relatives of 57 percent of clients with family connections.

Currently, this "anything-in-the-past-year" measure is the most detailed quality-of-care measure used. We surveyed mental health providers about clinician-family communication to determine from a staff viewpoint the frequency of contact and its purpose, function, and outcomes.

Methods

The study setting was an urban university-based community psychiatry program consisting of two standard office-based clinics, one assertive community treatment team, and one program providing services of medium intensity. As part of a quality management effort in 1998-1999, one-fifth of all clients diagnosed as having schizophrenia and one-fifth of all clients diagnosed as having affective disorders were randomly selected from the clinic roster. A total of 214 clients were selected.

The primary therapist of each client filled out a 19-item questionnaire about his or her contact with the client's family. The questionnaire asked about the frequency, timing, format, and purposes of the contact; the primary family member contacted; the obstacles and effort involved; and the therapist's satisfaction with and judgment about the benefits of contact. (The survey instrument is available from the authors). Thirty-six therapists completed the questionnaires. Most were women (N= 23) and Caucasian (N=29), and most worked in the standard office-based clinic (N=21).

Results

Of the 214 clients, 119 (56 percent) were women, and 136 (64 percent) were people of color (mostly African Americans). The clients' mean±SD age was 45.5±10.38 years. A slight majority (113 clients, or 53 percent) were diagnosed as having schizophrenia; 100 (47 percent) were diagnosed as having affective disorders. The therapists reported that 114 clients (53 percent) lived with biological family members or others acting as family.

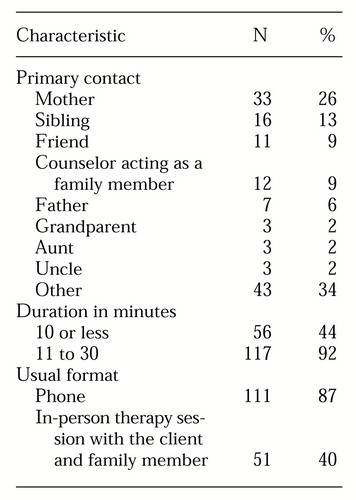

The therapists reported at least one contact in the past year with a family member or someone acting as a family member for 128 clients (60 percent). For 87 of these clients (68 percent) the therapists reported one, two, or three contacts in the past year. For 41 clients (32 percent) the therapists reported one or more contacts a month. The therapists reported that contacts tended to occur during crises for 57 of the clients (44 percent). As shown in Table 1, contacts were most often by phone and frequently brief. Mothers were the most frequently contacted family members.

The therapists reported that the most common reason for contact was to help a family member solve a problem about a client's behavior (80 clients, or 63 percent). Other commonly cited reasons were to provide the family with emotional support (74 clients, or 58 percent), to enlist the family in helping with the client's assessment or history (64 clients, or 50 percent), to provide education or information to the family member (62 clients, or 48 percent), or to help the family member during a crisis (52 clients, or 41 percent). Some reasons were much less common. They included conducting family therapy (31 clients, or 24 percent), obtaining financial information (21 clients, or 16 percent), checking on the client's status (four clients, or 3 percent), or helping with problems not related to the client (six clients, or 5 percent).

The therapists reported feeling satisfied with their family contacts in 97 cases (76 percent). Satisfaction was mixed for 26 cases (20 percent). The therapists felt dissatisfied in five cases (4 percent). Most therapists believed that contact with family members benefited the client. For 66 clients (52 percent) they felt that some benefit was gained, and for 57 clients (45 percent) they felt that a lot of benefit was gained.

In terms of benefit for family members, the therapists reported some benefit in 74 cases (58 percent) and a lot of benefit in 43 cases (34 percent). Therapists reported that no effort was needed to achieve family contact for 36 clients (29 percent), and some effort was needed for 79 clients (63 percent). They reported that a lot of effort was needed in only 11 cases (9 percent).

The therapists reported that for 82 clients (38 percent) no family contact was made. When they were asked about barriers to contact, family-related barriers were not frequently cited. For example, for only nine clients (11 percent) did the therapist say that the family was too distant. The families of only seven clients (9 percent) did not respond or refused to respond to outreach efforts.

Therapist-related barriers to contact were more frequently reported. For 43 of the 82 clients whose family members were not contacted (52 percent), the therapist reported that he or she perceived it would be of no benefit.

In the case of client-related barriers, the therapists reported that 26 of the 82 clients (32 percent) refused to give permission to contact their relative. In 25 cases in which no family contact was made (30 percent), the therapists cited the clients' own minimal family contact.

We used logistic regression to test multivariate relationships among therapists who did and did not have contact with clients' family members, with clients' age, gender, race, and treatment site as covariates. Therapists of younger clients were more likely to have family contact than those of older clients (odds ratio=.969, 95% confidence interval= .941 to .999, p<.05), as were therapists of clients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (OR=2.21, CI=1.23 to 4.02, p<.01). In addition, clients of the traditional clinics were less likely than clients of the community-outreach team to have family contact (OR=.360, CI=.163 to .791, p<.05).

Discussion

This study characterized the nature of family-clinician contacts in an urban mental health clinic from the therapists' perspective. Almost two-thirds of therapists reported contact with their clients' families, but the interactions were infrequent and often occurred around crises. However, in consonance with best-practice standards, therapist-family contact was oriented to problem solving, support, and education rather than traditional family therapy.

The therapists in our study reported higher rates of family contact than were found in previous studies (8,9). Because we did not use a claims database or chart review to measure family contact, as the previous studies did, the discrepancy in rates of contact suggests that the contacts in our study were not billed and were perhaps not documented in clients' charts. However, because these brief, informal contacts with family members occurred outside of formal psychoeducational programs, their benefits are uncertain.

The majority of therapists in our study perceived that their family contact was helpful to the client and to the family member, and that contacting a family member required minimal effort. When asked to cite barriers to contact, common stereotypes about families' not being available or interested were not endorsed. Rather, in 52 percent of cases in which a family member was not contacted, the therapist believed that such contact would not benefit the client. These data suggest the importance of assessing the validity of therapists' perceptions.

In about 10 percent of all cases, the therapists reported that patients refused to give permission to contact a family member. In a similar proportion of cases, the therapists reported that they did not contact a family member because the patient had minimal contact with his or her family. Clients' refusal to give consent and a client's lack of connection with family members are often cited anecdotally as reasons that therapists do not have contact with families. If the results of this study are found to be generalizable to other populations of persons with severe mental illness, our results may provide an estimate of how often these phenomena occur.

The therapists' reports of having more contact with mothers than with fathers is in keeping with findings of other studies. However, the substantial role siblings sometimes play is often overlooked. In addition, we found that a wide range of people filled family roles, which suggests that research and services should use broad definitions of "family."

The findings that therapists were more likely to have contact with family members of younger persons, those with schizophrenia, and those served by outreach teams are also consistent with those of other studies and make sense given that family members of younger persons are more likely to be available and that outreach teams often have more resources (8).

The support and services that families do and do not receive and the perceptions of families, clinicians, and consumers about support and services are neglected and important issues in outcomes research and treatment. The results of this study are more detailed than those of previous studies. However, the study was limited because it tapped a single sample and assessed clinician-family contact from the retrospective viewpoint of clients' primary therapists only. Gathering further details and triangulating these results with data from consumers and family members about their views of family-provider contacts are important next steps.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jill RachBeisel, M.D., and Eileen Hastings, R.N., M.S.W.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, 701 West Pratt Street, Room 476, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of contacts by 36 therapists with family members of 128 clients with serious mental illness

1. Adamec C: How to Live With a Mentally Ill Person. New York, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

2. Cochrane JJ, Goering PN, Rogers JM: The mental health of informal caregivers in Ontario: an epidemiological survey. American Journal of Public Health 87:2002-2008, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Marsh DT: Families and Mental Illness: New Directions in Professional Practice. New York, Praeger, 1992Google Scholar

4. Hatfield A, Coursey RD, Slaughter J: Family responses to behavioral manifestations of mental illness. Innovations and Research 3:41-49, 1999Google Scholar

5. Dixon L: Providing services to families of persons with schizophrenia: present and future. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2:3-8, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-9, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Dixon L, Goldman HH, Hirad A: State policy and funding of services to families of adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:551-552, 1999Link, Google Scholar

8. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233-238, 1999Link, Google Scholar

9. Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al: Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:611-617, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Greenberg JS, Greenley R, Kim HW: The provision of mental health services to families of persons with serious mental illness. Research in Community and Mental Health 8:181-204, 1995Google Scholar