Enlisting Indigenous Community Supporters in Skills Training Programs for Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study evaluated the generalization of skills training for severely and persistently mentally ill individuals who were paired with indigenous supporters. The supporters monitored the individuals' environments and prompted them to use their skills. METHODS: A total of 85 individuals with severe and persistent mental illness received six months of skills training. Forty-five of the participants received support from an individual of their choosing. The other 40 participants did not have supporters. At the end of the six-month skills training period, the supporters' participation was officially terminated, although they were encouraged to remain in their role for as long as both parties felt comfortable. The effects of the support were measured in terms of interpersonal functioning, acquisition and retention of the skills, psychopathology, global functioning, and satisfaction. Several process measures were also collected. RESULTS: The support procedures were evaluated favorably by both patients and supporters. The interpersonal functioning of the group with supporters was found to be significantly better than that of the nonsupported group at six- and 12-month follow-ups. No differences were found between the groups in symptoms—which were minimal during the entire training period—or skills learning and retention. CONCLUSIONS: The effects of support are likely applicable for a variety of individuals, supporters, and facilities. Indirect evidence suggested the importance of providing support for the supporters.

Several reviews have concluded that skills training helps persons with severe and persistent mental illness acquire functional behaviors and retain skills largely intact for up to two years. This positive outcome was found across diverse settings, trainers, and skills (1,2,3,4,5). However, the reviews conclude that there is little evidence that individuals transfer behaviors from training to their own living environments, except in the rare case where the training and living environments are the same, such as long-stay inpatient facilities. The general approach to increasing skills transfer is to provide support in the form of advice about adapting the skills to fit the living environment, encouragement to try them in that environment, and assistance when the skills are unsuccessful.

The types of support that have been studied include support provided by participants in a common psychoeducational program (6), a telephone "help line" of peers who provided rapid assistance (7), and teaching individuals to contact community treatment staff and obtain their own support after brief inpatient treatment (8).

These methods centralize the support, delivering it from a common location that fits the needs of the supporters. Some authors have suggested that skills transfer could be increased if the support was provided in actual living environments and if the environment was tailored to maximize the performance of the skills (9,,10).

Although case managers could provide on-site support, they typically have large caseloads and limited knowledge about each environment, and they would have to consider their transportation costs and time. Alternatively, an indigenous supporter—that is, someone who lives with and interacts with a mentally ill person, is routinely accessible, and who knows well that person's particular environment—could be enlisted to prompt the use of learned skills when opportunities arise and help deliver the expected outcomes.

A relationship between a mentally ill person and a supporter could also be valuable per se. Social support has been correlated with decreased inpatient admission rates, higher levels of functioning, fewer negative symptoms, good physical health in stressful conditions, and enhanced coping responses (11,12,13,14,15,16).

Despite the potential value and minimal cost of implementing the role of indigenous supporter, no studies of recruiting and training them and measuring their effects on outcomes have been conducted. This article reports the results of such a study.

Methods

Participants

A total of 85 persons with severe and persistent mental illness who were receiving care from the case management teams of a public mental health system participated in the study. The criteria for selection were age between 25 and 55 years; a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, a schizoaffective disorder, or a major mood disorder; at least one episode of treatment in an inpatient facility of at least five days' duration in the previous 12 months, but not more than a cumulative total of two years of inpatient treatment in the past five years; living in a residential care facility; and not enrolled in a long-term rehabilitation program.

Sixty-four participants (75.3 percent) had been diagnosed as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and the remainder with a major mood disorder. Fifty-three participants (62.5 percent) were male. Sixty-eight (80 percent) were Caucasian, ten (11.8 percent) Hispanic, five (5.8 percent) African American, and two (2.4 percent) Asian. Sixty-six (77.6 percent) had never been married, 15 (17.6 percent) were divorced or separated, and four (4.7 percent) were married. Average age was 36.2 years, and average education was 12.1 years.

Procedures

All 85 participants received six months of skills training conducted with four of the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills modules—medication management, symptom management, recreation for leisure, and basic conversation skills (17). The training was administered in a group format for three hours a day, three days a week. Absences were made up on the two days during which no training was scheduled.

Participants were enrolled in sequential cohorts of eight over a two-and-a-half-year period, from June 1996 to January 1998. The support procedures were developed and funded approximately halfway through the study period. Hence the first 40 participants received training without the support procedure, and the next 45 received skills training with support. Four of the participants who were receiving skills training only and six of those who were receiving training plus support did not complete the program. Comparison of the demographic characteristics of the remaining participants showed no significant differences between the groups.

During their first month of skills training, the 45 participants in the training-plus-support group were asked to list people in their environments who were accessible and pleasant and were knowledgeable about the environments' resources and limitations, and who would likely serve as supporters. Participants ranked their selections in order of preference, and project staff contacted the highest-ranked persons and solicited their agreement to help. Only two refused, and in both cases the second-highest-ranked person was contacted and agreed to assist.

At the end of the first month of skills training, project staff met with each participant-supporter pair to explain the support procedures. The procedures consisted of structured meetings between participant and supporter to review the participant's use of the skills learned during training; to explore the causes of a less-than-satisfactory use—for example, environmental obstacles or lack of opportunity; and to generate a method to improve skills use. No constraints were placed on the frequency, topics, or duration of a pair's meetings. The pair was told that the procedures were intended to be pleasant and rewarding, and it was left to the pair's discretion to tailor the meetings to fit each partner's needs and comfort.

The supporters were given an overview of the format and content of the skills training modules. Each pair was provided with a support plan rating sheet that listed the skill taught in each module. Space was provided to record whether a meeting focused on the opportunities to use the skills, the obstacles that impeded their use, or reinforcement for using the skills. Project staff met biweekly or monthly with each pair to review the use of the rating sheet, monitor data collection, and resolve problems. At the end of the six months of skills training, project staff ceased to meet formally with the pairs, but the pairs were encouraged to continue their relationship with staff members. Staff members provided informal assistance to a pair upon request by either member.

Measure of participant-supporter relationship

After the 45 participants had nominated their supporters and the supporters had agreed to take part in the study, the participants were asked the reasons for nominating a particular person, the duration of their relationship, and, on average, how often they contacted one another, how long these contacts lasted, and the general topics of the contact. Participants also rated the amount of emotional, functional, and informational support they received from and gave to their nominees on a 5-point scale, from none to a lot. Emotional support was defined as "a caring relationship [with] someone who makes you feel better when things aren't going well"; functional support was with "someone who would run an errand for you"; and informational support was with "someone who provides facts, advice, or directions."

At each meeting with a pair, project staff asked the supporters to rate their satisfaction with their role on a 7-point scale, from terrible to delighted. Participants rated their satisfaction with the entire process on the same scale at the beginning and at the end of the support procedures.

Outcome measures

Measures of outcome were administered to both the training-only group and the training-plus-support group at four intervals: immediately before the skills training program began, immediately after it was completed, and at six months and 12 months after program completion. The measures consisted of the Assessment of Interpersonal Problem Solving Skills (AIPSS) (18), the Comprehensive Module Tests (CMTs) (17), the UCLA Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (expanded BPRS) (19), and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (20).

The AIPSS is an individually administered interview-role play test comprising 13 brief videotaped interpersonal vignettes, ten of which portray problems such as requesting the use of a new neighbor's phone to arrange for installation of utility services. Each vignette is viewed separately, and the interviewer asks questions to assess respondents' recognition of a problem, their understanding of its nature, and the adequacy of the solution they generate to solve it. Respondents then role play their solutions, and the role play is scored for problem-solving adequacy, the quality of its paralinguistic elements, such as voice volume and eye contact, and its overall adequacy.

The CMTs—one per module—are interview-role play quizzes of the respondent's knowledge and performance of the specific information and skills presented in that module. Answers or role plays are scored using detailed criteria listed on the recording sheet. The expanded BPRS is a semistructured interview that assesses 24 symptoms of psychopathology, scored on a 7-point scale from not at all to severe. The GAS is a summary rating of the respondent's social and psychiatric functioning based on all relevant information from the respondents and their informants.

The outcome measures were administered by two interviewers who were hired solely to collect data and who were not informed about the support procedures. Participants were cautioned by project staff not to discuss their treatment with the interviewers. The interviewers were trained to administer and score the tests by the UCLA Intervention Research Center for Psychosis. Training involved didactic presentations, role-played interviews, and ratings of videotaped criterion administrations to a minimum kappa of .80 for each BPRS rating and a minimum correlation (r) of .80 for CMT total. The project director reviewed approximately 25 percent of the test administrations just after their completion to monitor the fidelity of the procedures and scoring.

Results

Supporters and the support relationship

Because of participants' moves and staff turnover, ten supporters were changed once during the five months of the support procedures, and three were changed twice. Of the 52 supporters chosen—39 initial choices and 13 replacements—32 (61.2 percent) were residential care staff or other immediately available staff members; 15 (28.6 percent) were friends, primarily someone who lived in the same residence or nearby, three (6.1 percent) were family members; and two (4.1 percent) were less-available staff members.

Thirty-six supporters (69 percent) were chosen because they were nice or responsive, 11 (21.2 percent) because they were knowledgeable and intelligent, and five (9.6 percent) because they were available. Fifty-four percent were female. The relationships between participants and supporters were almost evenly divided between short-term (less than six months) and long-term (more than 24 months). The short-term relationships were generally with residential staff and the long-term with friends and residential care owners.

Participants and supporters met less frequently during the training program than before (mean±SD= 10.52±5.27 times a month compared with 17.7±9.16). However, the meetings were longer (30 minutes minimum compared with 2.36±2.81). Before the program, the topic of most of the meetings (88 percent) involved leisure or unspecified activities. During the program, 38 percent of the meetings involved skills training materials and 52.4 percent involved leisure and miscellaneous activities. The skills training interactions focused on the more structured and user-friendly training materials such as the self-assessment rating sheet in the medication management module and the persistent symptoms rating sheet in the symptom management module. The materials were clinically relevant and provided a neutral format for discussing personal information.

Only one supporter characteristic was associated with the frequency of the pairs' interactions: satisfaction of the supporters with their role. The more supporters were satisfied with their role, the more often they met with participants (r=.635, p<.001) and the more often they used the meetings to discuss the skills training and its associated materials (r=.461, p<.01). No other characteristic—for example, age, BPRS scores, education, or length of the relationship—was associated with the frequency of the meetings.

Both participants and supporters were quite satisfied with the relationships. For all three types of support measured, participants rated themselves as receiving significantly more support than they gave (emotional, t=6.97, df=37, p<.001; informational, t=6.03, df=37, p<.01; functional, t=2.84, df=37, p<.01).

Outcomes

The data from each outcome measure were analyzed separately with a split-plot factorial analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using the pretest scores as the covariate, treatment conditions as the between-subjects variable (training only versus training plus support), and test time as the within-subjects variable (posttraining and at six-month and 12-month follow-ups). Each ANCOVA was conducted with programs from the SAS package.

Expanded BPRS. The results indicated that all participants' symptoms were rated at subclinical levels at all assessment points (average scores ranged from 1.62 to 2.7; a score of 3 or less is subclinical). Given this low level of symptoms, the ANCOVA main effects and the interaction between condition and test time were not significant.

CMTs. As with the BPRS, the ANCOVA main effects and the condition-test time interaction were not significant for any of the four CMTs. Analyses of the pre-post changes for each CMT (2×2 split-plot factorial ANCOVA) yielded the same pattern of results across the four; a significant main effect for time—lowest F=6.17, df=1, 75, p<.01—and insignificant effects for condition and the condition-time interaction. Participants significantly and substantially improved their knowledge and performance of the materials and skills presented in a module. Furthermore, they retained their knowledge and skills with no loss during the follow-up period.

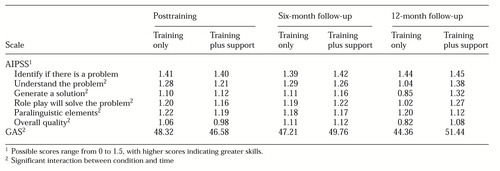

AIPSS. Unlike the interaction effects for the BPRS and the CMTs, the ANCOVA effects were significant for four of the six AIPSS scales. Table 1 presents the adjusted posttraining and follow-up means for the AIPSS scales. Analyses of the interactions with tests of simple main effects indicated that while both groups achieved the same adjusted posttraining means, the training-plus-support group continued to improve during the follow-up period in participants' understanding of the nature of the problem (F=8.09, df=2, 75, p<.01), the adequacy of their generated solutions (F=6.62, df=2, 75, p<.01), the quality of the role play content for solving the problem (F=4.04, df=2, 75, p<.02), and the overall quality of their role play.

In contrast, the training-only group declined on all AIPSS scales so that participants were significantly poorer at the last follow-up in their understanding of the problem during their role plays (F=5.34, df=1, 75, p<.02), adequacy of their solutions (F=7.62, df=1, 75, p<.01), quality of the content (F=4.98, df=1, 75, p<.02), and overall performance (F=4.44, df=1, 75, p<.03).

GAS.The GAS results paralleled those for the AIPSS (see Table 1). The ANCOVA interaction effect was significant, with the training-only group deteriorating slightly during follow-up compared with improvements in the training-plus-support group. The differences between the groups were significant at the last follow-up (F=3.25, df=2, 90, p<.05).

Discussion and conclusions

The results demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of enlisting supporters to reinforce skills training in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. All participants nominated someone who could serve as a supporter, and virtually all the nominees agreed to help. Because neither the history of the pairs' relationships nor the characteristics of the partners affected the frequency and consistency of the support, the procedures may apply to diverse participants, supporters, and living arrangements.

Furthermore, the meetings required a considerable amount of the supporters' time, which they willingly gave despite the absence of any tangible incentives. Perhaps the highly structured nature of the procedures encouraged supporters to complete them; supporters commented that they felt particularly comfortable completing tasks such as reviewing the rating sheets and checklists with the participants. These tasks required no interpretive judgments and could be finished within their time schedules.

Supporters' satisfaction with their role was associated with the frequency of meetings. This finding and the participants' perception of the relationships as one-sided giving by the supporters suggest the need to support the supporters. The declining frequency of the meetings over the five months may partly reflect a decline in supporters' enthusiasm, although it may also reflect a streamlining of the meetings. By paying careful attention to supporters' attitudes and providing ongoing support, their enthusiasm may be maintained.

It should be noted that participants' perceptions of the type and amount of support they received were not associated with their satisfaction. Emotional and informational support were apparently as satisfying as functional support, which may be more difficult to provide because it often requires resources such as money and time.

The outcome measures provide tentative evidence of the efficacy of the support procedures. The AIPSS results are similar to findings that social support for persons with severe and persistent mental illness is correlated with enhanced coping responses when they are confronted with a problem or stressful situation (12,16). The results are particularly encouraging because the improvements continued after the meetings were no longer required. The majority of participants remained in close and frequent contact with their supporters, and the brief and informal exchanges provided opportunities to practice interpersonal skills and give informational and emotional support as needed.

Participants' subclinical symptoms and their almost perfect retention of the skills taught in the modules precluded evaluation of the effects of the support on either outcome. The design and implementation of the project had several limitations that reduce the generalizability of its results and point to areas for future research. The project was conducted with a quasi-experimental design, and the differences between participants in the first half of the project (training only) and the second half (training plus support) may have affected the AIPSS results. This effect is unlikely, however, since the two groups were not significantly different on any measure at participants' enrollment, and there were no changes in the procedures for referral to residential care or the supply of residential care beds.

The meetings focused the partners on the modules and ignored development of the mutual interests that sustain long-term relationships. However, the meetings did not impede such development—they simply did not address these interests.

The supporters need support. Administrative support could be given by making the procedures an expected and valued responsibility that is routinely monitored and rewarded by the residence operators. Participants' case mangers could give supporters periodic emotional, informational, and functional support. Supporters may have to be replaced periodically, given the typical turnover of residential care staff and the movement of individuals from residence to residence. Slightly more than 25 percent of the supporters changed during the five months of the procedures. The effects of such changes could be minimized if support were available from several sources. Peers who are familiar with a residence could span the change in staff supporters, and family or case managers could span changes in residences.

Mr. Tauber is a research associate and Dr. Wallace is a visiting professor of medical psychology in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, Intervention Research Center for Psychosis. Dr. Lecomte is an assistant professor of psychiatry at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Address correspondence to Dr. Wallace at Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants, P.O. Box 2867, Camarillo, California, 93011-6022 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Adjusted mean scores on the Assessment of Interpersonal Problem Solving Skills (AIPSS) and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) for 36 participants who received skills training and 39 who received skills training plus support

1. Benton MK, Schroeder HE: Social skills training with schizophrenics: a meta-analytic evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 58:741-747, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Dilk MN, Bond GR: Meta-analytic evaluation of skills training research for individuals with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:1337-1346, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Heinssen RK, Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Psychosocial skills training for schizophrenia: lessons from the laboratory. Schizophrenia Bulletin, in pressGoogle Scholar

4. Penn DL, Mueser KT: Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:607-617, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Scott JE, Dixon LB: Psychological interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:621-630, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dobson D: Long-term support and social skills training for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:1195-1196, 1996Link, Google Scholar

7. Lane AB: Combining telephone peer counseling and professional services for clients in intensive psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services 49:312-314, 1998Link, Google Scholar

8. Kopelowicz A, Wallace CJ, Zarate, R: Teaching psychiatric inpatients to re-enter the community: a brief method of improving continuity of care. Psychiatric Services 49:1313-1316, 1998Link, Google Scholar

9. Brekke JS, Long JD, Nesbitt N, et al: The impact of service characteristics on functional outcomes from community support programs for persons with schizophrenia: a growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:464-475, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cook JA, Pickett SA, Razzano L, et al: Rehabilitation services for persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Annals 26:97-104, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Cresswell CM, Kuipers L, Power MJ: Social networks and support in long-term psychiatric patients. Psychological Medicine 22:1019-1026, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hultman CM, Wieselgren I-M, Öhman A: Relationships between social support, social coping, and life events in the relapse of schizophrenic patients. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 38:3-13, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Macdonald EM, Jackson HJ, Hayes RL, et al: Social skills as a determinant of social networks and perceived social support in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 29:275-286, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Anthony WA, Liberman RP: The practice of psychiatric rehabilitation: historical, conceptual, and research base. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:542-559, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Gottlieb BH, Coppard AE: Using social network therapy to create support systems for the chronically mentally disabled. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health 6:117-131, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Starkey D, Flannery RB: Schizophrenia, psychiatric rehabilitation, and healthy development: a theoretical framework. Psychiatric Quarterly 68:155-166, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Training in social and independent living skills: applications and impact in chronic schizophrenia, in Which Psychotherapies in Year 2000? Edited by Cottraux J, Legeron P, Mollard E. Amsterdam, Swets & Zeitlinger, 1992Google Scholar

18. Donahoe CP, Carter MJ, Bloem WD, et al: Assessment of interpersonal problem-solving skills. Psychiatry 53:329-339, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, et al: Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: 'the drift busters.' International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:221-244, 1993Google Scholar

20. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar