The Effect on Diagnostic Rates of Assigning Patients to Ethnically Focused Inpatient Psychiatric Units

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined whether assigning patients from three ethnic groups—blacks, Latinos, and Asians—to three psychiatric inpatient units that provided culturally appropriate treatment to those groups would affect rates of diagnosis of various psychiatric disorders. METHODS: Retrospective administrative data for 5,983 inpatients at a large urban community hospital with several ethnically focused units were examined. The data represented 10,645 admissions between 1989 and 1996. Chi square analyses and Stuart-Maxwell tests of symmetry and homogeneity were used to assess the relationship between matching patients to ethnically focused units and the rates of major psychiatric illnesses among Asian, black, and Latino patients compared with whites. RESULTS: Ethnic differences in diagnostic rates were consistent with the results of previous studies. Black patients had more diagnoses of psychotic disorders and fewer diagnoses of affective disorders than other ethnic minorities or whites, and Latino patients had more nonspecific diagnoses. Matching inpatients to ethnically focused units did not have a marked effect on patterns of diagnoses among black patients, but an association was observed for Latino patients, particularly those who had only one admission. No significant diagnostic differences were found between Asian patients and whites, irrespective of whether the Asian patients had been ethnically matched to a specialty focus unit. CONCLUSIONS: The effect of referring inpatients with serious mental illnesses to an ethnically focused psychiatric unit varied by ethnic group, probably because each specialty unit functioned differently, depending on the needs of its particular patient population.

The relationship between ethnicity and psychiatric diagnosis has been debated since the 1970s, when several authors suggested that ethnic minorities, particularly blacks, were subject to diagnostic bias (1,2,3). Since then, several studies have examined the prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses among ethnic minorities in an attempt to discover whether observed differences in psychotic and affective disorders represented real differences in prevalence rates or were due to misdiagnosis.

It is generally agreed that differences in diagnostic rates do exist, although the underlying causes of such differences are unclear. Overall, blacks are more likely than whites and other groups to receive diagnoses of psychotic disorders than of affective disorders (3,4,5,6,7), whereas Latinos receive relatively more diagnoses of affective disorders (7,8,9,10,11). The findings for Asians are inconsistent. Some studies have suggested that Asians receive more diagnoses of depression than whites (12,13,14,15), whereas others have shown that Asians receive comparatively more diagnoses of psychosis (7).

There are probably a number of reasons for such diagnostic differences between Asians, blacks, Latinos, and whites, including differences in actual prevalence rates, differences in treatment and referral practices, and misdiagnosis. Nevertheless, it has become clear that understanding the role of culture and ethnicity in the development and expression of mental illness is important for appropriate diagnosis and for treatment.

We took advantage of a unique resource—several ethnically focused inpatient programs at San Francisco General Hospital, a large urban community hospital—to explore the relationship between ethnic matching and psychiatric diagnoses. The specialty teams, which have been described in greater detail elsewhere (16,17,18,19), were developed initially to teach cultural competency in psychiatric practice to trainees. Each team focuses on a particular ethnic group, such as Asians, blacks, or Latinos, or another group with specialized needs, such as women, gay and lesbian patients, or persons with HIV infection or AIDS, and attempts to diagnose and treat psychiatric inpatients in a culturally competent manner.

Several of the staff on the ethnic specialty teams share the cultural background of the patients they serve. Many are bilingual or multilingual. Members of the various specialty focus teams are fluent in Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, Tagalog, Vietnamese, and ten other Asian languages and Chinese dialects.

Patients who do not speak English are assigned preferentially to an appropriate focus unit. Because of the high volume of patients treated in the county hospital, other patients are assigned to focus units on the basis of the availability of beds at the time of admission. Thus these units are necessarily heterogeneous in ethnic composition. However, in general, most patients on the Asian focus unit are of Chinese or Filipino descent, and most patients on the Latino unit are of Mexican or Central American descent.

Although specialized treatment programs are becoming more common, virtually nothing is known about the effect of such programs on diagnosis or treatment outcome. In this study we examined the first of these effects—the relationship between ethnic matching and psychiatric diagnosis. We examined the relationship between ethnic matching and treatment outcome in a separate study, also published in this issue (17).

We expected that rates of diagnoses in our study sample would differ among ethnic minorities, as has been found by others (1,2,3,4,5,6,7). We hypothesized that nonspecific diagnoses would be more common among non-English-speaking ethnic minorities than among English-speaking minorities because of difficulties in making definitive diagnoses.

Because the staff on the ethnically focused units at San Francisco General Hospital are specially trained in cultural competency, including recognition of culturally specific presentations of common psychiatric disorders, we also hypothesized that matching patients to these units would reduce the rate of misdiagnosis and thus reduce differences in diagnostic rates between matched ethnic minorities and whites. For example, the staff on the focus unit for black patients are aware that bipolar disorder among black persons can frequently be confused with schizophrenia because of a higher frequency of hallucinations and delusions among blacks (3,5). Thus we hypothesized that the members of this team would be less likely than the staff on the other units to misdiagnose schizophrenia among black patients.

Methods

Data sources

Data were extracted from the management information system database of the San Francisco County Department of Community Mental Health Services, placed into SAS 6.12 format for data management purposes, and subsequently imported into Stata 6.0 for statistical analysis. Approval for the study was obtained from the committee for human research for the University of California, San Francisco, and from the division of mental health, substance abuse, and forensic services of the Department of Public Health for San Francisco County.

Study sample

We examined data for all psychiatric inpatient admissions between 1989 and 1996 to three specialty focus units—an Asian focus unit, a Latino focus unit, and a black focus unit. Patients were included if they were between the ages of 20 and 80 years and were Asian, Latino, black, or white. Patients from other ethnic groups (6 percent of admissions), including persons of Native American, Middle Eastern, Russian, and mixed or unknown descent, were not included. The final study sample consisted of 5,983 psychiatric patients, representing 10,645 admissions. (Data were occasionally missing for key variables for some patients, so the sample sizes for some of the results presented in this paper were less than 5,983.) Asians—persons of Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Laotian, Cambodian, Korean, Pacific Islander, and other Southeast Asian descent—represented 15 percent of all inpatient admissions (1,634 admissions). Latinos—persons of Mexican, Spanish, Latin American, Puerto Rican, and Cuban descent—represented 11 percent of all inpatient admissions (1,120 admissions). Blacks represented 26 percent (2,827 admissions), and whites represented 48 percent (5,064 admissions).

Patients who were admitted to an ethnically appropriate unit—for example, an Asian patient who was admitted to the Asian focus unit—were considered to be "matched." Patients who were admitted to a unit that focused on an ethnic background other than their own—for example, a black patient who was admitted to the Latino unit—were considered to be "unmatched." A total of 1,258 Asian admissions (77 percent), 1,578 black admissions (56 percent), and 764 Latino admissions (68 percent) were matched. White patients, who were admitted to all ethnically focused units as well as to a unit that did not have a specialty focus, were considered a separate group and were used as the basis for comparison.

Most patients (4,966, or 83 percent) spoke English as their primary language; 299 (5 percent) spoke only Spanish, 479 (8 percent) spoke only an Asian language, and 239 (4 percent) spoke other or unknown languages. We included only English-speaking persons in all analyses except those that examined the relationship between language and diagnosis. Among admissions for patients who did not speak English, 778 Asian admissions (84 percent), 45 black admissions (56 percent), and 439 Latino admissions (79 percent) were matched. Fifty-two percent of all Asian admissions and 48 percent of all Latino admissions were for non-English speakers. In contrast, 3 percent of all black admissions and 3 percent of all white admissions were for non-English speakers,

The number of admissions for individual patients varied greatly, ranging from 1 to 47 throughout the seven-year study period. To eliminate dependencies in the data set, we used one randomly chosen admission per patient. The only exception was the analysis of the effect of ethnic matching on diagnoses of non-English-speaking persons, in which the samples were small and all admissions were used. For within-subject comparisons, information on all patients who had at least two admissions was extracted from the larger database. For these patients, we created a record for each possible pair of matched and unmatched admissions and randomly chose one pair for analysis, which produced a total of 447 matched pairs of admissions.

Diagnostic categories

All diagnoses were made by the treating clinicians using DSM-III-R criteria. We divided diagnoses into six major categories: adjustment disorders, bipolar affective disorder, major depressive disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, and psychosis not otherwise specified. Because the absolute numbers of patients with anxiety disorders, delusional disorders, substance use disorders, organic disorders, and other disorders were very small—each representing less than 5 percent of the total number of admissions—we excluded these diagnoses from the analyses.

Statistics

Inpatient admissions were used as our unit of analysis. We used chi square analyses for all between-subject tests of association and used Stuart-Maxwell tests of symmetry and homogeneity (20,21) for within-subject comparisons of diagnostic rates between admissions that were ethnically matched and those that were not.

Results

Effect of ethnicity

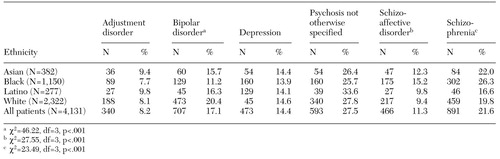

The diagnostic rates for the various ethnic groups are listed in Table 1. We observed differences in diagnoses between ethnic groups (χ2=88.7, df=15, p<.001) that were consistent with what has been previously observed. Overall, compared with white patients, black patients had fewer diagnoses of affective or adjustment disorders and more diagnoses of psychotic disorders, whereas Latino patients had more diagnoses of adjustment disorders or unspecified psychotic disorders. Specifically, black patients had lower rates of diagnoses of bipolar disorder and higher rates of diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia than all other ethnic groups. Latinos had more diagnoses of psychosis not otherwise specified and fewer diagnoses of schizophrenia. Diagnostic rates for Asians did not differ systematically from those for whites for any psychiatric diagnosis.

Effect of language

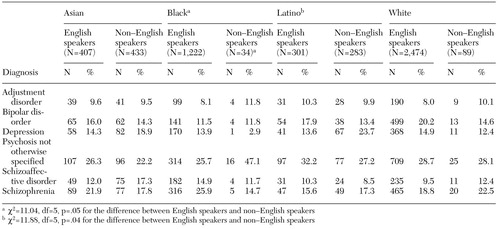

Chi square analyses were used to compare diagnoses between patients who spoke English and those who did not. The results are summarized in Table 2. For all ethnic minority groups, language was related to differences in diagnostic rates. Among Asians, non-English speakers had more diagnoses of depression and schizoaffective disorder than English speakers and fewer diagnoses of bipolar disorder, psychosis not otherwise specified, and schizophrenia, although the difference was not statistically significant. Black patients who did not speak English had higher rates of nonspecific diagnoses, including adjustment disorders and psychosis not otherwise specified, and lower rates of diagnoses of depression or schizophrenia. Latino patients who did not speak English had higher rates of diagnoses of depression and lower rates of diagnoses of bipolar and schizoaffective disorder.

Effect of matching

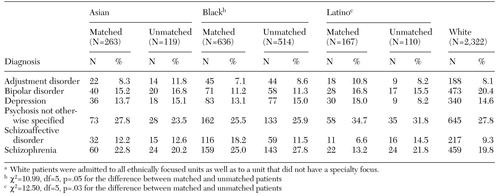

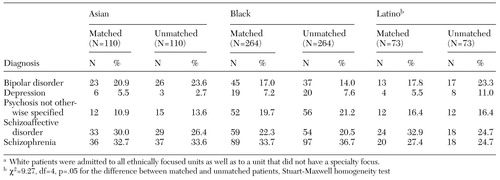

As noted above, patients who were admitted to an ethnically appropriate unit were considered to be "matched." Diagnostic rates for ethnically matched and unmatched English-speaking patients are listed in Table 3. Within each ethnic group and relative to white patients, matched and unmatched black and Latino patients—but not Asian patients—had significantly different diagnostic rates. Overall, matched Latino patients had more diagnoses of depression and fewer diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia than did unmatched Latinos, and matched black patients had higher rates of diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder and lower rates of diagnoses of depression than did unmatched black patients.

Contrary to what we expected, diagnostic rates for unmatched black patients were closer to those for white patients than were rates for matched black patients (χ2=91.2, df=8, p<.001). The exception was schizophrenia, for which diagnostic rates for matched blacks were somewhat closer to those for whites, although rates for both matched and unmatched black patients were higher than those for whites. Among Latino patients, diagnostic rates for affective disorders were closer to the rates for whites among matched patients, although the rates for other disorders were closer to the rates for whites among unmatched patients (χ2=19.4, df=8, p=.035). No significant diagnostic differences were observed between Asian patients—matched or unmatched—and white patients.

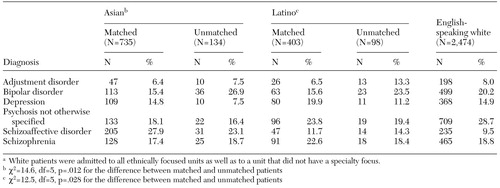

The diagnostic rates for ethnically matched and unmatched admissions for non-English-speaking Asian and Latino patients are listed in Table 4. Matched Asian patients had higher rates of diagnoses of depression and schizoaffective disorder and lower rates of diagnoses of bipolar disorder than unmatched Asian patients, whereas matched Latino patients had more diagnoses of depression, psychosis not otherwise specified, and schizophrenia than unmatched Latinos and fewer diagnoses of adjustment disorder and bipolar disorder. In general, the rates for affective disorders among matched Asians were closer to those among whites than among unmatched Asians. For matched Latino patients, the rates of nonspecific diagnoses, such as adjustment disorder and psychosis not otherwise specified, more closely resembled those for whites than those for unmatched Latino patients.

Within-subject comparisons

To address the question of whether observed differences in diagnostic rates between patients from the three ethnic groups who were admitted to ethnically appropriate units and those who were not was a function of differential selection (persons with particular diagnoses being more likely than others to be matched) or of different diagnostic practices for matched versus unmatched patients, we performed a within-subject comparison. The results are summarized in Table 5. Diagnostic rates for matched and unmatched admissions were compared in a random sample of English-speaking patients who had had multiple admissions. The within-subject comparison showed no significant diagnostic differences between matched and unmatched admissions for Asian or black patients. However, there was some evidence that diagnoses were assigned differently between matched and unmatched admissions for Latino patients; matched patients were more likely to receive a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (32.9 percent compared with 24.7 percent) and less likely to receive a diagnosis of depression (5.5 percent compared with 11 percent).

Admission rates

We used chi square analysis to examine admission rates for matched and unmatched patients separately for each ethnic group. Each patient was assigned to one of four categories on the basis of their total number of admissions during the seven-year study period—only one admission, two to five admissions, six to ten admissions, and more than ten admissions. For all ethnic groups, a majority of patients had only one admission during the study period. Patients who had only one admission accounted for 66 percent (110 patients) of matched Latinos and 52 percent (57 patients) of unmatched Latinos, 55 percent (351 patients) and 63 percent (326 patients) of matched and unmatched blacks (χ2=10.11, df=3, p=.02), and 65 percent (172 patients) and 66 percent (78 patients) of matched and unmatched Asians.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, our hypothesis that treating patients in ethnically focused inpatient units would "normalize" rates of various diagnoses among ethnic minorities by bringing them closer to rates observed among whites was not supported by the results of this study. We did find that the patterns of variation in the overall rates of psychiatric diagnoses were similar to those reported elsewhere. We also found an association between language and diagnostic variations for all ethnic minorities. However, only among black patients did we find higher rates of nonspecific disorders among non- English speakers.

Although the reasons for diagnostic differences among the ethnic groups we studied are unclear, clinician or institutional bias has been frequently cited as a likely contributor. We hypothesized that matching psychiatric patients to ethnically focused inpatient units would minimize any potential bias and thus result in diagnostic rates that were more similar across ethnic groups and more similar to rates among whites. Although ethnic matching appeared to have an effect on diagnostic rates, this effect was not consistent. Rather, the effects of ethnic matching varied by ethnic group.

Asian patients

Contrary to our expectations, no systematic differences were found between Asians and whites for any major psychiatric diagnosis, nor between Asian patients who were treated in ethnically focused units and those who were not. In fact, the only statistically significant differences were between matched and unmatched Asians who did not speak English, for whom matching was associated with lower rates of diagnoses of adjustment disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia as well as rates of diagnoses of depression that more closely resembled those for whites.

These findings can perhaps be explained by the fact that the Asian focus unit, created in 1980, is the oldest and best-established of the specialty focus units at San Francisco General Hospital and is well integrated into the overall workings of all the psychiatric inpatient units in the hospital. Because of the relatively small number of Asian patients admitted to the hospital each year, a majority of Asian patients are admitted to the Asian focus unit at some point in their psychiatric history (77 percent of all Asian admissions and 84 percent of non-English-speaking admissions). For patients who are admitted to other units, consultation and translation services are available. Thus it is possible that the effect of the Asian focus team over the years has been to reduce differences in diagnostic rates between Asian and white patients throughout the hospital.

Black patients

As has been observed in previous studies, the black psychiatric inpatients in our sample were more likely to receive diagnoses of psychotic disorders and less likely to receive diagnoses of affective disorders than white patients or patients from other ethnic minorities. Matching did not appear to have an effect on these diagnostic patterns. With the exception of schizoaffective disorder, which was more prevalent among black patients on the black focus unit, ethnically matched and unmatched black patients had similar rates of all major diagnoses. In addition, contrary to what we expected, the rates for unmatched black patients were closer to the rates for white patients than were the rates for matched black patients for all diagnoses except schizophrenia, for which rates were consistently higher for matched and unmatched black patients than for white patients.

To better understand the relatively high proportion of diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder among patients treated on the focus unit for black patients, we conducted a within-subject comparison. This analysis, which showed no significant diagnostic differences for black patients when they were on matched units than when they were on unmatched units, suggested that misdiagnosis was unlikely to be the reason for the higher rate of schizoaffective disorder among matched black patients. The difference can instead be explained by practices for referral to the black focus unit. Given the vast number of admissions, some admission criteria are necessary for all the specialty focus units, in addition to the criteria related to the unit's specialty focus. On the focus unit for black patients, where language is not an issue, preference might be given to difficult-to-manage patients, such as those with severe diagnoses. Schizoaffective disorder, the most common diagnosis on the black unit, has the poorest treatment outcome of the severe mental illnesses treated at San Francisco General Hospital; it is associated with the most frequent rehospitalizations and the longest stays (17).

The observation that black patients with multiple admissions were more likely to be treated on the black focus unit supports our hypothesis of preferential admission on the basis of severity of illness. Although black patients had about the same number of admissions to matched and unmatched units, patients who had only one admission during the seven-year study period were significantly less likely to have been admitted to the black focus unit than patients who had had multiple admissions.

Latino patients

As we expected, overall diagnostic patterns for the Latino patients in our sample were similar to those observed in other studies. Although no differences were observed in the rates of diagnoses of affective disorders, Latinos were given fewer severe psychotic-spectrum diagnoses—that is, more diagnoses of psychosis not otherwise specified and fewer diagnoses of schizophrenia—than were patients of other ethnic groups. Latino patients who were treated on the Latino focus unit were more likely than Latinos treated on other units to be given a diagnosis of major depression and less likely to be given diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia. Matching was also associated with a smaller gap between Latinos and whites in diagnoses of affective disorders, at least among English speakers.

The reasons for the diagnostic differences among Latino patients, both matched and unmatched, are not straightforward. However, these differences can perhaps be explained by differences in admission practices as well as by some differences in diagnostic practices. Even though Latinos, particularly those treated on the special unit, had lower rates of diagnoses that are associated with poor prognoses, the within-subject comparison showed that Latino patients who had more than one admission more often received diagnoses of severe disorders when matched than when unmatched.

This finding suggests that, for Latino patients who had multiple admissions but not for those who did not, the Latino focus team was more likely to assign a diagnosis associated with a poor outcome than were the other focus teams. In contrast with the patients assigned to the Asian and black focus units, a majority of patients who were matched to the Latino focus team had only one admission. It is possible that because most matched Latino patients were not readmitted, those who had multiple admissions were viewed as more severely ill by members of the Latino focus team than by members of the other teams, who had more experience with patients with severe illness and multiple admissions. This difference in clinicians' experience may have produced a contrast effect when the severity of diagnoses among Latino patients was being judged.

The results of this study are consistent with previous observations that ethnicity has an important—although as yet not clearly understood—relationship to psychiatric diagnosis. The findings also suggest that treating patients from ethnic minority groups in focused units, which has been shown to have an impact on treatment outcome (22,17), has less clear effects on diagnostic rates.

We hypothesized that because the staff on the ethnically focused psychiatric units would probably have a greater awareness of culturally specific variations in presentation of symptoms, the main effect of ethnic matching would be to "normalize" diagnostic rates among ethnic minorities, particularly for patients who did not speak English and who thus might have had a greater risk of misdiagnosis. This hypothesis was not supported. The relationship between ethnic matching and diagnosis appears to be a complex one, and no clear patterns emerged from this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Stephen R. Murray, M.D., Ph.D., and Bruce Stegner, Ph.D., for their input into the study design and execution and Francis Lu, M.D., for comments on the manuscript.

Dr. Mathews is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, 0810, La Jolla, California 92093-0810 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Glidden is with the department of epidemiology and biostatistics and Dr. Hargreaves is with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

|

Table 1. Primary diagnoses of 4,131 inpatients, by ethnic group

|

Table 2. Primary diagnoses of inpatients, by ethnic group and whether they were English speakers

|

Table 3. Primary diagnoses of English-speaking inpatients, by ethnic group and whether they were admitted to the appropriate ethnically focused unit ("matched") or not ("unmatched")a

a White patients were admitted to all ethnically focused units as well as to a unit that did not have a specialty focus.

|

Table 4. Primary diagnoses of non-English-speaking inpatients, by ethnic group and whether they were admitted to the appropriate ethnically focused unit ("matched") or not ("unmatched")a

a White patients were admitted to all ethnically focused units as well as to a unit that did not have a specialty focus.

|

Table 5. Primary diagnoses of inpatients, by ethnic group and whether they were admitted to the appropriate ethnically focused unit ("matched") or not ("unmatched")a

a White patients were admitted to all ethnically focused units as well as to a unit that did not have a specialty focus.

1. Thomas A, Sillen A: Racism and Psychiatry. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1972Google Scholar

2. Pope HG, Lipinski JF: Diagnosis in schizophrenia and manic depressive illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:811-828, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Adebimpe VR: Overview: white norms and psychiatric diagnosis of black patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:279-285, 1981Link, Google Scholar

4. Baskin D, Bluestone H, Nelson M: Ethnicity and psychiatric diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 37:529-537, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mukherjee S, Shukla S, Woodle J, et al: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia in bipolar patients: a multiethnic comparison. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:1571-1574, 1983Link, Google Scholar

6. Lawson WB, Hepler N, Holladay J, et al: Race as a factor in inpatient and outpatient admissions and diagnosis. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:72-74, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Flaskerud JH, Hu LT: Relationship of ethnicity to psychiatric diagnosis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 18:296-303, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Vernon SW, Roberts RE: Use of the SADS-RDC in a tri-ethnic community survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:47-52, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Burnam MA, Hough RL, Escobar JI, et al: Six-month prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic whites in Los Angeles. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:687-694, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Karno M, Hough RL, Burnam MA, et al: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic whites in Los Angeles. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:695-701, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Jones BE, Gray BA, Parson EB: Manic-depressive illness among poor urban Hispanics. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:1208-1210, 1983Link, Google Scholar

12. Aldwin C, Greenberger E: Cultural differences in the predictors of depression. American Journal of Community Psychology 15:789-813, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kuo WH: Prevalence of depression among Asian-Americans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172:449-457, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Yamamoto J, Yeh EK, Loya F, et al: Are American psychiatric outpatients more depressed than Chinese outpatients? American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1347-1351, 1985Google Scholar

15. Ying YW: Depressive symptomatology among Chinese-Americans as measured by the CES-D. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1486-1487, 1988Link, Google Scholar

16. Zatzick DF, Lu FG: The ethnic/minority focus unit as a training site in transcultural psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry 15:218-225, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Mathews CA, Glidden D, Murray S, et al: The effect on treatment outcomes of assigning patients to ethnically focused inpatient psychiatric units. Psychiatric Services 53:830-835, 2002Link, Google Scholar

18. Gee KK, Du N, Akiyama K, et al: The Asian focus unit at UCSF: an 18-year perspective, in Cross Cultural Psychiatry. Edited by Herrera JM, Lawson WB, Sramek JJ. New York, Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

19. Black M: Development of a client-centered inpatient service for African Americans, in Cross Cultural Psychiatry. Edited by Herrera JM, Lawson WB, Sramek JJ. New York, Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

20. Stuart A: A test for homogeneity of the marginal distributions in a two-way classification. Biometrika 42:412-416, 1955Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Maxwell AE: Comparing the classification of subjects by two independent judges. British Journal of Psychiatry 116:651-655, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu LT, et al: Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: a test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 39:533-540, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar