Community-Based Long-Term Care for Older Persons With Severe and Persistent Mental Illness in an Era of Managed Care

Abstract

The authors describe current needs and trends in the mental health care, including long-term care, of older persons with severe and persistent mental illness. The literature suggests that emerging models of managed long-term care hold promise for integrated services but do not currently address the specialized mental health needs of this patient group. The authors review issues in financing long-term mental health care, including controversies over fee-for-service and carve-out and carve-in arrangements. Without mechanisms to adequately finance services, adjust for risk, and measure outcomes, the authors conclude, managed care arrangements will be in conflict with the goal of high-quality care for older adults with severe and persistent mental illness. Proposed directions for future models of care for this group include integration of mental health and medical services, integration of specialized geropsychiatric services with developing community-based long-term care systems, blended financing under shared risk arrangements, and assurance of accountability and outcomes under managed care.

How will the long-term care needs of an aging population with severe mental illness be met in the future? Long-term care in America is undergoing dramatic reform in response to escalating Medicare and Medicaid expenditures. These expenditures consume 18 percent of the current $1.6 trillion federal budget, and they are predicted to increase to 22 percent of the $2 trillion budget by 2002 (1). Among the greatest anticipated increases are for nursing home and home health care, with about a fourth of all Medicare beneficiaries in need of these services (2).

Managed care and home- and community-based alternatives to institutionalization are currently being promoted as responses to the rising state and federal expenditures (3). Although individuals with severe and persistent mental illness are overrepresented in the long-term-care population (4) and account for a disproportionate amount of mental health care costs (5), there is an alarming lack of attention to services for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness.

About 2 percent of persons aged 55 and older in the United States have severe and persistent mental illness (6), and the number of older adults with severe and persistent disorders is expected to double in the next 30 years (7). Because the current system of long-term mental health care for older adults with these disorders is inadequate (8) and service provision is largely driven by reimbursement policies, managed care is likely to have profound effects on mental health care for this population.

Health policy issues have been debated in relation to the general topic of managed mental health care (9,10), and the future challenges of providing mental health services to an aging population (11,12). However, little attention has been focused on the potential impact of managed care on the subgroup of older persons with severe and persistent mental illness who have the most intensive long-term mental health needs.

In this paper we provide an overview of risks and potentials inherent in future systems of managed mental health and long-term care for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness. First, we briefly consider the needs of this subgroup and then address current trends in long-term care and fee-for-service mental health services, specifically focusing on community-based long-term care. Next we discuss relevant managed care issues, including the capacity of managed health care to provide the intensity and types of needed services, the question of whether mental health services should be carved in or carved out, and managed care outcomes for mental health services. Finally, we describe community-based models of long-term care that offer potential for improved care, and we address implications for the future.

Service needs

Older adults with severe and persistent mental illness are defined in this paper as persons age 65 and over with lifelong or late-onset severe mental illness with residual impairment. As generally defined, severe and persistent mental illness includes diagnoses such as schizophrenia, delusional disorder, bipolar disorder, and recurrent major depression (8). Older adults who develop these disorders in early adulthood often have smaller social support systems and fewer financial resources than those with late-onset illness (13), but both share many clinical features and the common need for long-term mental health care services.

Older persons with severe and persistent mental illness frequently have substantial functional difficulties, medical comorbidity, and associated cognitive impairment (14,15) and therefore require a comprehensive array of services. However, current mental health services for elderly persons are largely fragmented and underutilized and do not adequately address their long-term mental health needs (8). Mental health services for this population are delivered through a variety of providers, including the general medical sector, where the focus is on acute care (8); community mental health organizations that typically underserve the elderly population (16); home health agencies that provide limited short-term mental health care; and geriatric long-term care programs that focus primarily on older adults with chronic physical disabilities or cognitive impairment (17).

Overall, deinstitutionalization has left many older persons with decreased access to mental health care in both community and institutional long-term settings (18,19). The majority of older adults with severe and persistent mental illness who reside in the community receive little support from the mental health system except for medication despite continued need, and those without family support are at greater risk of being institutionalized (13,20). These factors underscore the pressing need to define and develop home- and community-based alternatives.

Long-term-care reform

The dramatic downsizing and closure of state hospitals over the last few decades has resulted in "transinstitutionalization" into nursing homes of many additional older persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Eighty-nine percent of all institutionalized older adults with severe and persistent mental illness reside in nursing homes (21). However, several trends suggest that institutions will play a declining role in future systems of long-term mental health care compared with community-based settings. First, the majority of older adults with severe and persistent mental illness live in the community (20) and prefer to remain there (Bartels SJ, Levine KJ, Miles KM, et al, unpublished manuscript, 1999). The more recent cohort of aging persons with severe and persistent mental illness have spent most of their lives in the community rather than institutional settings. Thus transinstitutionalization from long-term state hospital units to nursing homes will become a vanishing phenomenon.

A second trend suggesting the declining role for institutions is the implementation of nursing home reforms under the federal Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (Public Law 100-203), with the goal of limiting the use of nursing homes for long-term mental health care. The reforms were implemented in response to increased psychiatric admissions to nursing homes after closures of state hospitals. This legislation requires preadmission screening for alternative placements for all persons suspected of having a serious mental illness.

Finally, escalating expenditures for nursing home care are stimulating dramatic reforms in reimbursement and policy. They include mandates by states to limit Medicaid expenditures by controlling the nursing home bed supply and cutting Medicaid reimbursement rates (22).

As the health care system shifts to accommodate the increasing number of individuals requiring chronic care, future projections suggest the greatest growth in services will be in home- and community-based settings (23). Dramatic changes in the structure and financing of long-term care and managed care are proceeding rapidly across the states, with a virtual lack of attention to the increasing numbers of older adults with severe and persistent mental illness who will have substantial service needs.

Fee-for-service Medicare and Medicaid financing

Currently, the majority of mental health and long-term-care services for older persons are financed through fee-for-service Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare is the federally funded health insurance program, providing insurance for persons age 65 and over and disabled persons under age 65. Medicare is composed of two parts: part A covers inpatient hospital care, 60 days of skilled nursing home care, and home health and hospice care. Part B provides reimbursement for physician and outpatient hospital services. Among the major limitations in Medicare coverage of mental health services are a required 50 percent copayment for psychotherapy services, a lack of general outpatient prescription drug coverage, limits on inpatient psychiatric days, and limited or no coverage of essential services such as adult day care, respite care, residential care, and home health care (24,25).

Home health care is an important alternative to institution-based care. However, Medicare covers only acute episodes of illness rather than long-term care. Mental disorders, including dementia, constitute only 2.8 percent of primary diagnoses for home health care (26). It is likely that home health care for psychiatric disorders will become even less available in coming years as Medicare reform results in cutbacks under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. After enactment of these reforms, 14 percent of U.S. home health care agencies, a total of 1,355 agencies, closed in 1998 (27).

Less than 3 percent of the total Medicare budget is spent on mental health, with less than half of these expenditures—approximately 1.5 percent—going to mental health services for the elderly population (28). Acute hospitalizations account for the vast majority of these expenditures (29).

Medicaid is the primary insurer for long-term care in nursing homes and the major source of reimbursement for state-funded services for disabled individuals, including individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. Because Medicaid is a joint federal and state program, with states paying up to 50 percent of the cost, states have substantial discretion in determining the eligibility criteria and types of mental health services covered.

For example, although many states offer coverage of prescription drugs, most have limitations in the form of copayments, limited refills, or other restrictions. States may also impose limitations on mental health care, including prior authorization and restrictions on the number of visits to providers. Medicaid reimbursement rates average 20 to 30 percent below prevailing market rates (30). Limiting the amount and scope of services and paying for psychiatric care at lower rates than for medical care create barriers to adequate mental health care for older patients.

In summary, the battle between the federal and state governments over the costs of Medicaid, as well as the limitations in Medicare coverage, leave many gaps in insurance coverage of mental health care for older adults. These gaps result in a fragmented treatment system and significant burden in out-of-pocket costs. In addition, rapidly increasing Medicare and Medicaid expenditures are resulting in the need to develop strategies that contain costs. The combination of gaps in coverage and service and escalating costs under a fee-for-service reimbursement structure has resulted in an explosion of managed care initiatives.

Can managed caremeet long-term needs?

It has been predicted that 35 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries will be in managed care plans by the year 2007, amounting to approximately 15.3 million people (2). This represents an increase of 12 percent per year from 13 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries in 1997. Although the managed care industry has promoted integrated services for people with long-term needs, its awareness of and response to chronic care are just beginning (3,23).

Comprehensive systems of managed health care such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs) offer the potential to provide comprehensive preventive, acute, and chronic care services at the forefront of innovative practices in geriatric medicine (3). However, the recent track record of Medicare managed care shows that older individuals with more severe disorders are underserved. Medicare beneficiaries in managed care plans are younger and healthier than those in the fee-for-service sector (31). Even though managed care plans continue to enroll less ill and less costly Medicare beneficiaries, the plans are retreating from providing services to older persons due to projected financial losses under current rate structures.

Nearly 100 managed care plans have announced their intent to withdraw from the Medicare managed care program during 1999 or to end their participation in regions of the country where reimbursement rates are lowest, especially rural areas. Due to this exodus by managed care, more than 444,000 high-risk Medicare patients in 29 states will be dropped by their HMOs this year (31).

The financial disincentives for managed care plans to enroll high-risk, high-cost patients are directly reflected in the types of mental health services that are currently provided in organizations such as HMOs. For example, specialized geriatric programs and clinical case management for older persons in HMOs tend to be inadequate or poorly implemented (32,33). Mental health services for older persons in primary care settings, including primary care HMOs, are likely to include minimal use of specialty providers and suboptimal pharmacological management (34), without the array of community support, residential, and rehabilitative services necessary to meet the needs of older persons with more severe mental disorders (35). In addition, most managed care organizations are ill prepared to meet the mental health needs of older persons with cognitive impairment disorders (36). These trends are likely to continue in managed care as long as data on effective service models are lacking and adequate methods to compensate for the financial risks of providing comprehensive long-term services to more complex and severely ill patients are unavailable.

Carved-in and carved-out mental health services

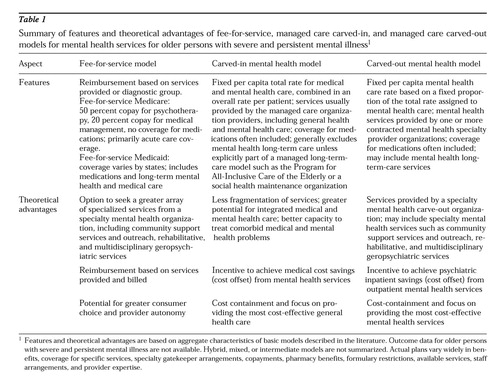

The debate over the best way to manage financial risk and to deliver mental health services in managed care has resulted in a variety of models that may be broadly grouped into two general categories. In some managed care organizations, mental health care is directly integrated into the package of general health care services that are covered and provided, or carved in. In others it is provided through a contract with a separate specialty mental health organization that provides services and accepts the risk, or carved out. Table 1 summarizes the financial and clinical features of these models of mental health managed care for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness, as well as the more traditional fee-for-service model.

Carved-in arrangements

Proponents of carved-in mental health services argue that this model of care better integrates physical and mental health care, decreases barriers to mental health care due to stigma, and is more likely to produce cost offsets and overall savings in general health care expenditures (36,37). These features are particularly important because older persons commonly have comorbid medical disorders and take multiple medications that may affect mental disorders; they typically avoid specialty mental health settings and incur significant health care expenses related to psychiatric symptoms (38).

Ideally, carved-in arrangements facilitate collaboration and communication between medical and psychiatric providers, avoiding arbitrary distinctions about medical versus psychiatric origins of symptoms and functional problems. Carved-in arrangements may be beneficial for the many older persons with common disorders who receive the vast majority of their mental health care from primary care providers.

However, several important caveats should be expressed about the potential benefits of mental health carve-in arrangements for older severely mentally ill persons. Although carved-in arrangements are likely to provide financial incentives for integrated medical and mental health services, functional integration is far from guaranteed. Unfortunately, mental health specialty services for older persons tend to be a low priority in managed health care organizations compared with medical and surgical specialty services (34).

In addition, the limited range of services provided in carved-in mental health care may be adequate for the bulk of individuals with diagnoses such as minor depression and anxiety disorders, but they are inadequate for older patients with severe mental disorders requiring intensive and long-term mental health care (25,37). The range of outreach, rehabilitative, residential, and intensive services needed is likely to exceed the capacity and expertise of most general health care providers.

Mental health carve-in arrangements may also be problematic economically. First, if mental health benefits are carved in as part of a benefit package, evidence from private-sector health plans suggests that without mandated parity, insurers will offer differential coverage of mental health care (9,10). Furthermore, if providers or payers compete for enrollees, a strong incentive will exist to avoid those expected to have higher costs from mental health problems, such as older persons with severe and persistent mental illness.

Finally, methods of adjusting payments to compensate for the increased financial risk of providing care to more severely ill enrollees under a capitated payment, known as risk adjustment, are quite difficult to apply for mental health care (39,40). For example, unless accurate risk adjustment strategies are developed for complex populations such as older adults with severe and persistent mental illness, the potential for substantial losses is likely to perpetuate the current lack of enthusiasm and services for this high-risk group among managed care organizations.

Carved-out arrangements

In contrast, proponents of carved-out arrangements for mental health services for older persons argue that separate systems of financing and services are likely to be superior for individuals who need specialty mental health services. In particular, they advocate that carved-out mental health organizations have superior technical knowledge, specialized skills, a broader array of services, greater numbers and varieties of mental health providers with experience treating severe mental disorders, and a willingness and commitment to provide services to high-risk populations (38).

In addition, proponents argue that mental health carve-out organizations permit economies of scale in providing the comprehensive array of rehabilitative and community support mental health services necessary to care for older severely mentally ill persons in the community. Finally, an incentive exists to reinvest savings from any decrease in inpatient service use into innovative outpatient alternatives. Although definitive studies are lacking, programs using carved-out services for younger populations have generally reported significant cost savings and favorable outcomes (41,42).

Unfortunately, data are lacking on outcomes and costs for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness in mental health carve-outs. From a clinical perspective, the downside of a carve-out arrangement is an increased risk for adverse outcomes due to fragmentation of medical and mental health care services. The potential for these adverse outcomes is especially pronounced for older persons, who are often taking many medications and who have multiple and often complex medical disorders. Failed communication or lack of collaboration between mental health and medical providers places the older person at particular risk of medication interactions, misdiagnosis, inaccurate assumptions about medical versus psychiatric causes of symptoms, and ambiguity about whose responsibility it is to ensure that appropriate community-based services are provided.

From a financial perspective, a variety of potential pitfalls should be mentioned. First and most important, mental health carve-out organizations assume the risk of providing services for a given population at a set negotiated fee. Downward pressures to contain or reduce costs may result in a unilateral reduction in the proportion of the overall health care dollar assigned for mental health services.

Second, a financial incentive exists for medical providers to assign and shift responsibility for comorbid conditions to mental health providers and vice versa. For example, because the allocations for medical and psychiatric services are fixed and segregated, it may be in the financial interest of a medical provider organization to inaccurately attribute the cause of a complex medical-psychiatric problem to mental illness, which would result in inadequate care and shift the cost burden to the mental health provider organization.

A third vulnerability of carve-out arrangements is the difficulty that they pose in demonstrating the benefits or cost savings of mental health services. Increased use of mental health services may appear to be more costly in a carve-out arrangement, even though such services may reduce overall health care costs by decreasing unnecessary medical visits and medical hospitalizations. However, this cost offset may not be evident in a carved-out arrangement.

Finally, the physical and mental comorbidity seen in older adults with severe and persistent mental illness (43) may reduce any anticipated financial advantages of carved-out services. If the mental health provider cannot appropriately manage services and costs associated with the combination of medical and mental health disorders, anticipated savings may not materialize.

Outcomes for high-risk populations under managed care

Outcome studies for older adults with severe and persistent mental illness under managed care are lacking. In general, studies of mental health outcomes for younger patients consistently find that managed care is successful in reducing mental health care costs. Reviews of costs under managed care carve-out plans in the private sector (44) and the public sector (45) indicate that these plans significantly cut costs.

However, clinical outcomes, especially for the most severely ill, are less clear. Data on clinical outcomes of mental health services under managed care are mixed and are particularly difficult to interpret due to differences in plans and populations served. Several studies suggest that outcomes are as favorable, or better, under managed care (46,47). In contrast, others report that the greater use of nonspecialty services for mental health care under managed care is associated with less cost-effective care (48) and that elderly and poor chronically ill patients may have worse health outcomes or outcomes that vary substantially by site and patient characteristics (49). These conflicting findings highlight the need for careful monitoring of outcomes for the most vulnerable subgroups.

A recent review of health outcomes in the managed care literature (50) concluded that no consistent patterns exist that suggest worse outcomes. On the other hand, when negative outcomes are found, they are more likely to occur for patients with chronic conditions, those with diseases requiring more intensive services, low-income enrollees in worse health, impaired or frail elderly persons, or home health patients with chronic conditions and diseases. These risk factors characterize the population of older adults with severe and persistent mental illness, suggesting that this group is at high risk of poor outcomes under managed care programs that lack specialized long-term mental health and support services.

In a summary of the U.S. literature on cost containment in mental health care, Wells (51) concluded that managed care results in significant cost savings in mental health care but suggested that reduced use of services under these approaches may result in poorer care, especially for those with the greatest psychological distress. To definitively address the question of mental health outcomes for older persons under managed care, the field must develop appropriate outcome measures and implement them in the evolving health care delivery systems. For example, we need measures that emphasize maintaining or improving independent functioning in the home and community rather than the workplace; limiting functional decline, rather than assuming that a person experiences an acute illness and then recovers; and optimizing quality of life in the context of medical and cognitive comorbidity (52).

Innovative models of managed long-term care

The challenge of containing escalating costs of long-term care while providing home- and community-based alternatives to institutional care has been the focus of several experiments in long-term care reform, including social HMOs, the Program for All-Inclusive Care of the Elderly (PACE), and state-managed long-term-care demonstrations.

First introduced as a four-site long-term-care demonstration project in the mid-1980s, social HMOs are intended to integrate acute care and long-term care within a managed care framework. The underlying concept is to provide acute and chronic care benefits under a single organization at financial risk, based on a prepaid capitation payment pooled from several sources including Medicare, Medicaid, member premiums, and copayments (33).

In contrast, PACE more narrowly focuses on individuals who meet eligibility criteria for nursing home care and assumes full risk under capitation for all long-term-care services, funded by monthly capitated payments from Medicare and Medicaid. Major features of the PACE program include a multidisciplinary team approach, service provision in a freestanding adult day health center, chronic care without caps on long-term-care expenditures, and routine annual health screening and preventive care (53). These model programs include many elements that might be adapted to the needs of older persons with severe and persistent mental illness to improve future long-term care for this population, including case management and multidisciplinary teams. However, program descriptions generally refer to mental health services as optional or do not refer to them at all (33,53).

Innovative state-initiated managed long-term-care demonstrations include programs for individuals dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare, who are among the highest users of acute and long-term health services (2). This group includes older persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Currently, multistate proposals are being developed to combine Medicaid and Medicare resources under a capitated plan that provides a full range of services, including community-based and institutional acute and long-term care (36,38). These initiatives have the potential to provide comprehensive long-term medical and mental health care through public insurance to a population with high rates of chronic mental and health disorders. However, with few exceptions, currently planned proposals do not feature mental health care as a core component or provider of services.

An alternative system of managed care with the potential to provide comprehensive services is exemplified by a single-payer national health care system. However, data from national comparisons are mixed. Single-payer health care systems in other countries are more likely to serve individuals with lower incomes and more severe mental illness than in the U.S., but overall access to specialty mental health services is no better and often involves longer waiting periods (54,55,56).

Implications for the future

How will older persons requiring long-term mental health care fare in an era of managed care? Current issues reviewed here suggest that there is cause for alarm; at the same time, new approaches to financing services hold promise if they are appropriately developed and harnessed. We have no clear examples of optimal models of organizing and financing comprehensive services for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness. However, this overview of the literature suggests several specific directions and guiding principles for future models.

Integration of mental health and medical services

Optimal services for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness require a close collaboration of primary medical care and mental health services. The high prevalence of medical and cognitive comorbidity in this group necessitates a clinical approach that recognizes the complex intermingling of medical and psychiatric disorders and the value of a collaborative medical-psychiatric approach. A variety of approaches to integrating medical and mental health care have been described, but meeting the needs of individuals with severe and persistent mental illness is especially problematic (37). Promising models of integrated care include location of medical and mental health providers at the same site, multidisciplinary medical-psychiatric treatment teams, provision of primary care in mental health clinics, provision of specialized mental health services in primary care clinics, and cross-trained medical-psychiatric providers.

The key clinical issue here is the creation of a collaborative care model across medical and mental health providers, regardless of whether the services are financially integrated (carved in) or separate (carved out). For example, the literature describes successful models of community-based mental health services that include a primary health care provider as an integral part of a mental health outreach team for older adults with severe and persistent mental illness (Levine KJ, Bartels SJ, unpublished manuscript, 1999) and the development of an affiliated primary care medical clinic specifically for individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (57).

Integration of specialized services and community-based care

Emerging systems of community-based long-term care across the states promise to provide many essential supports and services necessary to maintain frail elderly persons with multiple medical disorders in home settings. These models of home- and community-based long-term care offer innovative approaches to providing medical and social services to older persons, yet generally do not include specialized services for long-term mental health care of persons with severe and persistent mental illness. To address these needs, such programs will need to partner with specialized geropsychiatric and community support services.

Although empirical data are lacking, a limited descriptive literature suggests that model programs must have specific clinical components to successfully maintain older adults with severe and persistent mental illness in the community. These components include intensive case management, general medical care, 24-hour crisis intervention, home-based mental health care, residential and family support services, caregiver training, multidisciplinary teams, active casefinding and outreach, and psychosocial rehabilitation (Levine KJ, Bartels SJ, unpublished manuscript, 1999). Descriptions of outcomes for these programs suggest that with adequate supports, the majority of older persons with severe and persistent mental illness can be maintained in the community at lower cost than in institutions and with equal or improved quality of life (58,59).

Blended financing and adjusting for illness severity

The greatest challenge to meeting the long-term-care needs of the growing numbers of aging persons with severe mental illness will be financial. Predictions of the bankruptcy of the Medicare trust fund and current projections for Medicaid expenditures require innovative and efficient use of these and other financial resources. Meeting the complex long-term medical and mental health care needs of older persons with severe and persistent mental illness under fee-for-service funding will require creative pooling of resources, including Medicare, Medicaid, and funding for aging services under federal and state block grant programs, as well as private insurance and limited personal funds. However, even with these measures, in the absence of dramatic reforms in the financing of health and long-term care for older persons, funds may be insufficient. Capitated care arrangements may be necessary to contain costs and to encourage use of the most cost-effective services.

A major goal of financing long-term care will be the reallocation of expenditures to support the development of home- and community-based alternatives. The most ambitious models of organizing and financing services for vulnerable populations of older persons provide integrated services under a single system responsible for both acute and long-term care. PACE, social HMOs, and state proposals for older persons who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid blend these sources of funding to create systems of acute and long-term care. All of these approaches share the common aim of redeploying funds from current costly nursing home care and hospital-based care to supported community alternatives. The goal of such programs is to blend these financial resources under capitation with an emphasis on supporting the least restrictive and least costly long-term-care services.

Managed care programs serving older persons with severe and persistent mental illness will need to incorporate risk adjustment strategies that account for the substantial costs associated with combined risks of older age, long-term mental disability, and medical comorbidity. For example, current reforms under the 1997 Balanced Budget Act include plans to eventually link Medicare capitation rates to health status through risk-adjusted payments (60).

However, due to the complex and imperfect science of accurately calculating financial risk associated with illness severity, intermediate or mixed models may be necessary. For example, it may be necessary to use partial capitation in which plans are reimbursed partly on the basis of fee-for-service expenses and partly on the basis of capitation (60). Similarly, the optimal model may be an intermediate arrangement between a full carve-in and a full carve-out. For example, geropsychiatric, community support, and rehabilitative mental health services might be provided by a specialized mental health provider organization that shares some risk with medical care providers as an incentive for collaborative care.

Ensuring accountability, advocacy, and outcomes

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that older persons with severe and persistent mental illness typify the most complex, vulnerable, resource-poor, and high-risk long-term-care patients. Service organizations that assume the financial risk for acute and long-term psychiatric and medical care will need to be appropriately reimbursed and held accountable for quality of care. In the absence of mechanisms to finance these services, adjust for risk, and measure outcomes, managed care arrangements will be in conflict with the goals of providing high-quality care for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness.

Conclusions

We have no simple answers to the question of how to best organize, finance, and deliver mental health and long-term-care services to older persons with severe and persistent mental illness. The integrated financing and organization of services promised in evolving models of managed long-term care offer the potential to eliminate fragmentation and inefficiencies and to create a much-needed continuum of medical, mental health, and social support services. Yet existing models fail to provide the specialized mental health services that are critical for serving this population in the community.

Persons who are frail, elderly, and chronically ill appear to be at greatest risk for poor outcomes under traditional models of managed care. Data that describe the costs and outcomes for innovative models serving this high-risk population are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by grant K07-MH-01052 from the division of aging of the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the suggestions of Christopher Colenda, M.D.

Dr. Bartels is associate professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical School and director of aging services research at the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 2 Whipple Place, Lebanon, New Hampshire 03766 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Levine is a research associate at the center. Dr. Shea is associate professor of health policy and administration at Pennsylvania State University in State College. This paper is part of a special section on meeting the mental health needs of the growing population of elderly persons.

|

Table 1.

Summary of features and theoretical advantages of fee-for-service, managed care carved-in, and managed care carved-out models for mental health services for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness1

1. The Economic and Budget Outlook: Fiscal Years 1998-2007. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, 1997Google Scholar

2. Komisar H, Reuter J, Feder J, et al: Medicare Chart Book. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Foundation, 1997Google Scholar

3. Kane RL: Managed care as a vehicle for delivering more effective chronic care for older persons. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 46:1034-1039, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Burns BJ, Taube CA: Mental health services in general medical care and in nursing homes, in Mental Health Policy for Older Americans: Protecting Minds at Risk. Edited by Fogel BS, Furino A, Gottlieb GL. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

5. Cuffel BJ, Jeste DV, Halpain M, et al: Treatment costs and use of community mental health services for schizophrenia by age cohorts. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:870-876, 1996Link, Google Scholar

6. Goldman HH, Manderscheid RW: Epidemiology of chronic mental disorder, in The Chronic Mental Patient, Vol 2. Edited by Menninger WW, Hannah G. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987Google Scholar

7. Cohen CI: Studies of the course and outcome of schizophrenia in later life. Psychiatric Services 46:877-879, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. George LK: Community and home care for mentally ill older adults, in Handbook of Mental Health and Aging, 2nd ed. Edited by Birren JE, Sloane RB, Cohen GD, et al. San Diego, Academic, 1992Google Scholar

9. Frank R, Koyanagi C, McGuire T: The politics and economics of mental health parity. Health Affairs 16(4):108-119, 1997Google Scholar

10. Frank R, McGuire T, Newhouse J: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50-64, 1995Google Scholar

11. Cohen D, Cairl R: Mental health care policy in an aging society, in Mental Health Services: A Public Perspective. Edited by Levin BL, Petrila J. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

12. Koenig HG, George LK, Schneider R: Mental health care for older adults in the year 2020: a dangerous and avoided topic. Gerontologist 34:674-679, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Meeks S, Murrell SA: Mental illness in late life: socioeconomic conditions, psychiatric symptoms, and adjustment of long-term sufferers. Psychology and Aging 12:298-308, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM: Functional impairments in elderly patients with schizophrenia and major affective illness in the community: social skills, living skills, and behavior problems. Behavior Therapy 28:43-63, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM: A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophrenia Research 27:181-190, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Light E, Lebowitz BD, Bailey F: CMHCs and elderly services: an analysis of direct and indirect services and service delivery sites. Community Mental Health Journal 22:294-302, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Robinson GK: The psychiatric component of long-term care models, in Mental Health Policy for Older Americans: Protecting Minds at Risk. Edited by Fogel BS, Furino A, Gottlieb GL. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

18. Knight BG, Woods E, Kaskie B: Community mental health services in the United States and the United Kingdom: a comparative systems approach, in Clinical Geropsychology, vol 7. Edited by Edlestein B. Oxford, England, Elsevier, 1998Google Scholar

19. Emerson Lombardo NB, Fogel BS, Robinson GK, et al: Overcoming Barriers to Mental Health Care. Boston, HCRA Research Training Institute, 1996Google Scholar

20. Meeks S, Carstensen LL, Stafford PB, et al: Mental health needs of the chronically mentally ill elderly. Psychology and Aging 5:163-171, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Burns BJ: Mental health services research on the hospitalized and institutionalized CMI elderly, in The Elderly With Chronic Mental Illness. Edited by Lebowitz BD, Light E. New York, Springer, 1991Google Scholar

22. Wiener JM, Stevenson DG: State policy on long-term care for the elderly. Health Affairs 17(3):81-100, 1998Google Scholar

23. Institute for Health and Aging: Chronic Care in America: A 21st Century Challenge. Princeton, NJ, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 1996Google Scholar

24. Gottlieb GL: Financial issues, in Comprehensive Review of Geriatric Psychiatry, 2nd ed. Edited by Sadavoy J, Lazarus LW, Jarvik LF. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

25. Bartels SJ, Colenda CC: Mental health services for Alzheimer's disease: current trends in reimbursement, public policy, and the future under managed care. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 6(2 suppl 1): S85-S100, 1998Google Scholar

26. Basic Statistics About Home Care. Washington, DC, National Association for Home Care, 1996Google Scholar

27. NAHC Home Health Agency Closings in 1998: A Report by the National Association for Home Care. Washington, DC, National Association for Home Care, 1999Google Scholar

28. Sherman J: Medicare's mental health benefits: coverage utilization and expenditures, 1992. Washington, DC, American Association of Retired Persons, Public Policy Institute, 1992Google Scholar

29. Culhane DP, Culhane JF: The elderly's underutilization of partial hospitalization for mental disorders and the history of Medicare reimbursement policies. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 26:95-112, 1993Google Scholar

30. Mace N, Emerson Lombardo N: Mental health care in the nursing home: a review of public policy, 1992. Boston, HCRA Research and Training Institute, 1992Google Scholar

31. Kassirer JP, Angell M: Risk adjustment or risk avoidance? New England Journal of Medicine 26:1925-1926, 1998Google Scholar

32. Pacala JT, Boult C, Hepburn KW, et al: Case management of older adults in health maintenance organizations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 43:538-542, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Kane RL, Kane RA, Finch M, et al: S/HMOs, the second generation: building on the experience of the first social health maintenance organization demonstrations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45:101-107, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Bartels SJ, Horn SD, Sharkey PD, et al: Treatment of depression in older primary care patients in health maintenance organizations. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 27:215-231, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Knight BG, Rickards L, Rabins P, et al: Community-based services for mentally ill elderly, in Mental Health Services for Older Adults: Implications for Training and Practice. Edited Knight B, Teri L, Wohlford P, et al. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1995Google Scholar

36. Mollica RL, Riley T: Managed Care, Medicaid, and the Elderly: An Overview of Five State Case Studies. Portland, Me, National Academy for State Health Policy, 1996Google Scholar

37. Mechanic D: Approaches for coordinating primary and specialty care for persons with mental illness. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:395-402, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Riley T, Rawlings-Sekunda J, Pernice C: Medicaid Managed Care and Mental Health. Medicaid Managed Care: A Guide for States, 3rd ed, vol 4: Challenges and Solutions: Medicaid Managed Care Programs Serving the Elderly and Persons With Disabilities. Portland, Me, National Academy for State Health Policy, 1997Google Scholar

39. Jencks S, Goldman H: Implications of research for psychiatric prospective payment. Medical Care 25:542-551, 1987Google Scholar

40. Frank R, McGuire T, Bae J, et al: Solutions for adverse selection in behavioral health care. Health Care Financing Review 18:109-122, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

41. Dickey B, Norton EC, Norman S, et al: Massachusetts Medicaid managed health care reform: treatment for the psychiatrically disabled, in Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research: Health Policy Reform and the States, vol 15. Edited by Scheffler R, Rossiter L. Greenwich, Conn, JAI Press, 1995Google Scholar

42. Stoner T, Manning W, Christianson J, et al: Expenditures for mental health services in the Utah Prepaid Mental Health Plan. Health Care Financing Review 18:73-93, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

43. Felker B, Yazel J, Short D, et al: Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:1356-1362, 1996Link, Google Scholar

44. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health coverage under managed care? JAMA 278:1533-1537, 1997Google Scholar

45. Busch S: Carving out mental health benefits to Medicaid beneficiaries: a shift toward managed care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:301-321, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Cole R, Reed S, Babigian H, et al: A mental health capitation program: I. patient outcomes. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1090-1096, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

47. Lurie N, Moscovice I, Finch M, et al: Does capitation affect the health of the chronically mentally ill? Results from a randomized trial. JAMA 267:3300-3304, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Sturm R, Wells KB: How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA 273:51-58, 1995Google Scholar

49. Ware JE, Bayliss MS, Rogers WH, et al: Differences in 4-year health outcomes for elderly and poor chronically ill patients treated in HMO and fee-for service systems. JAMA 276:1039-1047, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Miller R, Luft H: Does managed care lead to better or worse quality of care? Health Affairs 16(5):7-25, 1997Google Scholar

51. Wells KB: Cost containment and mental health outcomes: experiences from US studies. British Journal of Psychiatry 166 (suppl 27):43-51, 1995Google Scholar

52. Bartels SJ, Miles KM, Levine K, et al: Improving psychiatric care of the older patient, in Clinical Practice Improvement Methodology: Effective Evaluation and Management of Health Care Delivery. Edited by Horn SD. New York, Faulkner & Gray, 1997Google Scholar

53. Eng C, Pedulla J, Eleazer GP, et al: Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): an innovative model of integrated geriatric care and financing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45:223-232, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Olfson M, Kessler RC, Berglund P, et al: Psychiatric disorder onset and first treatment contact in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1415-1422, 1998Link, Google Scholar

55. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: Mental health care use, morbidity, and socioeconomic status in the United States and Canada. Inquiry 34:38-49, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

56. McFarland B, Bigelow D: Mental health services in Canada and the United States. Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Health Services Research Meeting, Washington, DC, June 21-23, 1998Google Scholar

57. Crews C, Batal H, Elasy T, et al: Primary care for those with severe and persistent mental illness. Western Journal of Medicine 169:245-250, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

58. Bernstein MA, Hensley R: Developing community-based program alternatives for the seriously and persistently mentally ill elderly. Journal of Mental Health Administration 20:201-207, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Trieman N, Wills W, Leff J: TAPS Project 28: does reprovision benefit elderly long-stay mental patients? Schizophrenia Research 21:199-208, 1996Google Scholar

60. Iezzoni LI, Ayanian JA, Bates DW, et al: Paying more fairly for Medicare capitated care. New England Journal of Medicine 26:1933-1938, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar