Effects of Client Interviewers on Client-Reported Satisfaction With Mental Health Services

Abstract

A study at two outpatient facilities compared two methods of collecting data on client satisfaction with mental health services provided by case managers and by physicians. A satisfaction survey instrument was developed with input from clients. A total of 120 clients were randomly assigned to be interviewed by either a staff member or a client. Clients from both facilities reported high levels of satisfaction regardless of the type of interviewer. Clients gave a significantly greater number of extremely negative responses when they were interviewed by client interviewers. No difference between the two groups was found in overall satisfaction with services received from case managers or physicians.

The use of client feedback to evaluate and improve the quality of service delivery is widely supported (1,2,3,4,5). One approach to eliciting clients' opinions is through satisfaction surveys. However, clients consistently report a high level of satisfaction with mental health services (123, 6, 7). The tendency toward conformity and overrating of satisfaction may be due to the client's relationship with the interviewing staff (6,7,8).

In addition, clients have typically not been involved in the development of survey instruments. When they are not consulted about or involved in the design of satisfaction surveys, instruments may not ask important questions and may be biased toward the perspectives of the service provider (1,2,6,8,9). Although it is recognized that traditional methods of collecting information about client satisfaction often produce invalid results, few new methods have been developed and implemented. The literature identifies the need to evaluate current methods and search for alternate methods of collecting information about clients' perceptions (4,6).

The purpose of this study was to compare methods of collecting data on client satisfaction with services using a questionnaire developed by staff and clients.

Methods

The study was conducted from September 1993 to September 1994 at the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry and Queen Street Mental Health Centre, both teaching facilities in metropolitan Toronto, Ontario. (Both were founding organizations of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, as well as the Addiction Research Foundation and the Donwoods Institute.) Two methods of data collection were used to collect information on client satisfaction: clients were interviewed by staff and by other clients.

Two staff interviewers and two client interviewers were hired at each facility. Criteria for selection of the interviewers were the ability to concentrate, ability to probe in a sensitive manner, skill at asking questions, listening skills, and ability to record information. Staff and client interviewers were trained in how to administer the questionnaire through didactic sessions and use of a videotape. Interrater reliability was evaluated using a videotaped session (r=.95).

A sample of clients from each facility was randomly selected for the study and randomly assigned to be interviewed by either the staff or the client interviewer. Thirty clients were assigned to each group, for a total of 60 participants at each site—a total of 120 participants. Clients were interviewed about their satisfaction with case management and physicians' services.

A new instrument was developed for this study because no standardized satisfaction questionnaire created by clients exists. It was developed using four focus groups comprising multidisciplinary staff and clients. Clients and staff experts reviewed the questionnaire and determined its face validity. Two client interviewers and one staff interviewer each conducted two pilot interviews successfully.

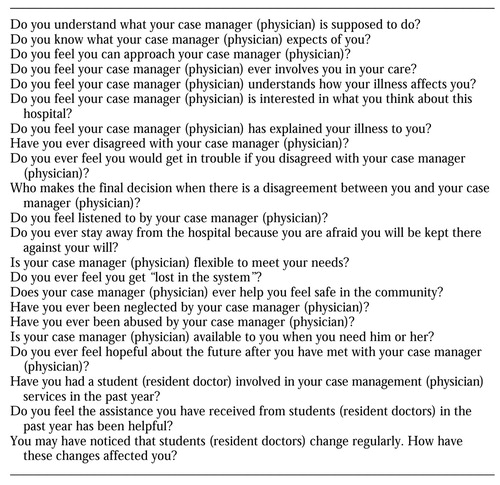

The instrument, shown in Table 1, asks 22 questions about specific aspects of case management services, followed by the same questions about physician services. The questions use a 5-point Likert rating scale; scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores denoting more positive ratings. Responses to individual questions are totaled for a rating of overall satisfaction.

Study participants were outpatient clients of each facility. To be included in the study, clients had to be between the ages of 18 and 65, to have a diagnosis of a major mental illness according to DSM-III-R criteria, to have a previous psychiatric hospitalization, and to be impaired in self-care, productivity, or social functioning as determined by a clinical intake assessment. Clients were excluded if they were cognitively impaired or incompetent to give informed consent.

Results

The results did not differ between the two facilities. Of the 120 participants, 50 (42 percent) were female. A total of 107 clients (90 percent) were single, divorced, or widowed. Fifty-five (47 percent) were unemployed, and 33 (28 percent) were employed full or part time. Most of the remaining clients were students, volunteers, or homemakers. Eighteen of the 120 clients (15 percent) had completed university or college, and 67 (56 percent) had completed high school. Ninety-two clients (78 percent) visited their facility once or more a week.

The two interviewed groups were similar across all variables except duration of illness. Clients interviewed by the client interviewers had been ill for a longer period than those interviewed by the staff members (9.18± 6.04 years versus 13.62±13.04 years; t=2.39, df=118, p<.02). The other variables examined were age, number of admissions, gender, marital status, education level, and frequency of visits to the facility.

Overall satisfaction levels were high. The mean±SD scores for the 120 clients were 3.1±5.9 for satisfaction with case management and 2.95±.67 for satisfaction with physicians' services. A significant difference was found by provider (F=9.20, df=1, 116, p<.003). Clients were more satisfied with services provided by their case manager than with those provided by their physician. However, the difference in scores was minimal and not clinically significant.

Interviewer effect was examined. The mean±SD scores for satisfaction with case management services were 3.12±.56 for the group interviewed by staff members and 3.08±.63 for the group interviewed by clients. The mean±SD satisfaction scores for physicians' services were 3.02±.58 for the staff-interviewed group and 2.87± .73 for the client-interviewed group. Analysis of variance used to examine interviewer effect and interviewer effect by service provider showed no difference in satisfaction between staff-interviewed and client-interviewed groups.

Extremely negative responses, defined as a score of 0 on any question, were examined separately. Analysis of variance showed an interviewer effect (F=5.09, df=1, 118, p=.026). Clients gave significantly more extremely negative responses to client interviewers than to staff interviewers. The results were the same when chronicity was added as a covariate in the analysis (F=5.50, df=1, 58, p<.022).

Extremely positive responses, defined as a score of 4 on any question, were also examined separately. Analysis of variance showed no interviewer effect. The results remained the same when chronicity was added as a covariate in the analysis.

Discussion and conclusions

The study yielded two findings. Clients from both facilities reported high levels of satisfaction regardless of the interviewer, and clients gave a significantly greater number of extremely negative responses when they were interviewed by clients.

The high rates of satisfaction found in this study are similar to those in other studies (123,6,7,10). One explanation is that clients were satisfied with the services received. Alternative explanations include the use of invalid instruments and data collection methods (2,9), clients' hesitancy to disclose their true thoughts or feelings due to their dependence on the system (8,7), and social desirability (that is, giving responses they believed would meet with interviewers' approval) (6).

Ninety-two of the 120 clients (78 percent) attended programs at their facility at least once a week and were therefore regarded as frequent users of service. However, dissatisfied clients may have left the program and were therefore not contacted for the study, or they may have been contacted and may have chosen not to be interviewed.

The second finding—that clients gave more extremely negative responses to client interviewers—is difficult to generalize to other groups because of the small number of interviewers. However, there appears to be an interviewer effect when a client is very dissatisfied with an aspect of service. This finding points toward the nature of the relationship that develops between the client interviewer and the client. Greater feelings of safety, trust, confidentiality, and privacy may have influenced the interviewees' disclosures to other clients.

A recommendation arising from this study is that programs should create opportunities for clients to address issues with other clients in privacy. If clients with extremely negative experiences speak more freely with other clients, the result will be more valid feedback. It may be beneficial to increase clients' involvement in all stages of program evaluation. Finally, making stronger efforts to reach infrequent users of services and dissatisfied clients is essential to providing relevant, effective, and meaningful client services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Paula White, M.S.W., C.S.W., for assistance with data collection and data entry and Cathy Spegg, M.B.A., for assistance with data analysis. Grant support was received from the Canadian Occupational Therapy Foundation, Ontario Mental Health Foundation, and Clarke Institute of Psychiatry research fund.

All the authors except Ms. Boydell are affiliated with the Clarke Institute site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 250 College Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5T 1R8 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Clark is program manager of the day center; Ms. Scott is administrative director of the society, women, and mental health program; and Dr. Goering is director of the health systems research unit. When this work was done, Ms. Boydell was a research scientist in the community support and research unit of the Queen Street site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. All the authors are also affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto.

|

Table 1.

Questionnaire about satisfaction with services received from case managers and physicians developed with input from clients of two outpatient mental health facilities

1. Gordon D, Alexander DA, Dietzan J: The psychiatric patient: a voice to be heard. British Journal of Psychiatry 135:115-121, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197-207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lebow JL: Research assessing consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment: a review of findings. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:211-236, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ridgway P: The Voice of Consumers in Mental Health Systems: A Call for Change. Burlington, University of Vermont, Center for Community Change Through Housing and Support, 1988Google Scholar

5. Holcomb WR, Adams NA, Ponder HM, et al: The development and construct validation of a consumer satisfaction questionnaire for psychiatric inpatients. Evaluation and Program Planning 12:189-194, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Elbeck M, Fecteau G: Improving the validity measures of patient satisfaction with psychiatric care and treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:998-1001, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Kalman TP: An overview of patient satisfaction with psychiatric treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:48-54, 1983Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Tanzman B: Researching the Preferences of People With Psychiatric Disabilities for Housing and Supports: A Practical Guide. Burlington, University of Vermont, Center for Community Change Through Housing and Support, undatedGoogle Scholar

9. Nelson CW, Niederberger J: Patient satisfaction surveys: an opportunity for total quality improvement. Hospital and Health Science Administration 35:409-427, 1990Google Scholar

10. Polowczyk D, Brutus M, Orvieto AA, et al: Comparison of patient and staff surveys of consumer satisfaction. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:589-591, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar