Use of Public Mental Health Services by Russian Refugees

Abstract

Objectives: This study identifies the demographic characteristics and patterns of mental health service use among Russian refugees in New York State. METHODS: Data from a 1995 statewide survey of characteristics of patients served by the New York State mental health system were analyzed using chi square statistics and logistic regression. RESULTS: The demographic characteristics and service-use patterns of Russian refugees are different from those of non-Russian refugees and nonrefugees. Russian refugees who used mental health services were likely to be older women with major depression who were enrolled in Medicaid and who were using those services for the first time. Relying heavily on themselves, family members, or friends as referral sources, they tended to use exclusively individual, outpatient services at voluntary, nonprofit agencies. CONCLUSIONS: Existing services systems must recognize the presence of Russian refugees. To improve access and service use, outreach efforts to the refugee community should be conducted, and services must be tailored to meet their mental health needs.

Between 1983 and 1995 more than 1.2 million refugees entered the United States. During this period, a major shift occurred in refugees' countries of origin, from Southeast Asia to the countries that made up the former Soviet Union. Refugees from the former Soviet Union constituted the largest group to arrive between 1988 and 1994; in 1995 alone, they made up 27 percent of the total number of refugees admitted to the United States (1).

The changing composition of the refugee population could lead to differences in service needs and patterns of service use between various groups of refugees. However, few empirical studies have systematically examined refugees' patterns of mental health service utilization. This shortcoming hampers the ability of policy makers and service providers to assess the responsiveness of current services. To determine whether service providers can accommodate rapid changes in the refugee population and to inform policy decisions, it is essential to obtain an updated picture of the use of mental health services by refugee populations. In the study reported here, we examined use of public mental health services by refugee populations in New York State.

Despite many studies addressing the social, cultural, and political aspects of the arrival in the United States of immigrants and refugees from the former Soviet Union, little information is available about their mental health status (2). Past research has suggested that Russian refugees experience a high prevalence of demoralization, depression, and somatic symptoms (2,3,4,5). However, most of these studies were based on small clinical samples, and none examined patterns of mental health service use. Although research on mental health service utilization by various ethnic groups has been done (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13), these studies have focused primarily on race or ethnicity, rather than refugee status. More information is needed on the particular characteristics of mental health service use among refugee populations.

Methods

This study used data from a survey of patient characteristics that collected demographic, clinical, and service use information about clients served by the New York State mental health system over a seven-day period during the fall of 1995. Local and state programs that are licensed or funded by the New York State Office of Mental Health reported information on each client served during the survey period. All visits or days in residence were recorded for each client. This format allows calculations of the number of clients served, as well as the number of service units each client used. The survey included information on diagnoses that were made by board-certified psychiatrists and recorded in the client's medical chart. During the week of the survey, 151,008 individuals received a total of 492,192 units of service.

The sample for this study included all clients who were designated by the facility as having been legally granted refugee status and who were thus eligible for the United States' refugee resettlement program. We believe that the sample size underestimated the number of refugees served because only individuals whose refugee status was known by the service providers were included. Therefore, this study is likely to have a conservative bias.

A total of 4,839 refugee clients received mental health services during the week of the survey. The language spoken by the client was used as an indicator of the country of origin. Although 40 percent spoke only English, almost half (44 percent) spoke only Russian or Russian in combination with English or other languages. Thus a large proportion of the refugee population who received mental health services in the sample was from Russia.

We examined the demographic characteristics and patterns of mental health service use among three groups of clients: Russian refugees, refugees who were not Russian, and nonrefugees. Demographic analyses used an unduplicated count of clients (N= 151,008). In the analyses of service use, clients were counted more than once if they received more than one type of service—for example, emergency services and outpatient services—during the week of the survey (N=173,424).

A bivariate analysis of association and logistic regression analyses were performed using SAS. Bivariate analyses were done to determine the association between the demographic, diagnostic, and service-use variables and refugee status. Because the variables were nominal, we used a Mantel-Haenszel statistic to measure general association (14). However, the value of the Mantel-Haenszel statistic approximated that of the chi square statistic in all tables due to the large number of cases in the study. A large sample size such as the one in this study is likely to yield statistically significant results even when the differences may be small. Therefore, caution must be used in interpreting the significance of the findings.

We conducted logistic regression analyses to assess the likelihood of mental health service use by refugees. The variables were dichotomized based on the results of the bivariate analysis. Odds ratios were computed to assess the likelihood that the variable occurred in one of the three groups of clients relative to the reference group for that variable.

Results

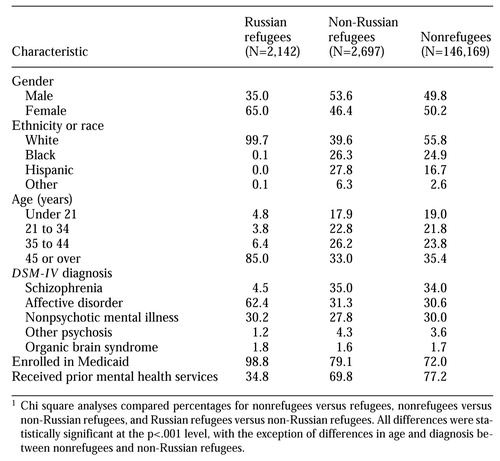

Table 1 shows selected demographic and clinical characteristics of the three groups of mental health services users—Russian refugees, non-Russian refugees, and nonrefugees. The Russian refugee group included a higher proportion of persons identified as non-Hispanic white, compared with the non-Russian refugee or the nonrefugee groups. The Russian refugees were more likely to be older and female. Russian refugees were twice as likely to be diagnosed as having an affective disorder and eight times less likely to be diagnosed as having schizophrenia. A closer look at more detailed diagnostic data (not shown) indicated that the majority of the Russian refugees with an affective disorder were experiencing major depression. Almost all Russian refugees were enrolled in Medicaid, and only about one-third had received prior mental health services.

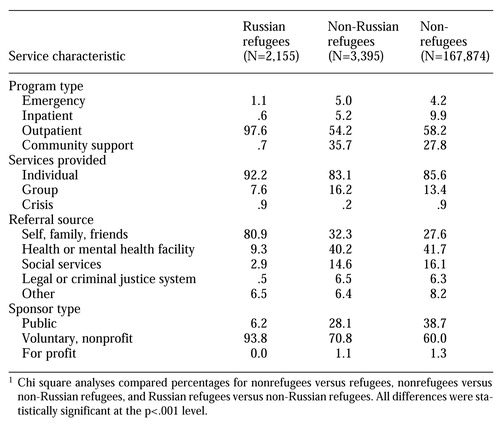

As Table 2 shows, Russian refugees were more likely to use outpatient services and to receive individual rather than group or crisis counseling. They were also much more likely to be referred to mental health services by themselves, family, or friends. Overall, the analyses suggested that the non-Russian refugees and the nonrefugees who used mental health services had quite similar characteristics and that the Russian refugees were a distinct group.

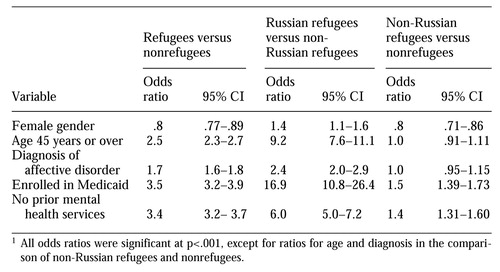

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis. The three-way comparisons—between refugees and non-refugees, then between Russian refugees and non-Russian refugees, and finally between non-Russian refugees and nonrefugees—highlighted the differences between refugee groups. The analysis showed that the characteristics of refugees differed from those of nonrefugees—for example, the odds ratios show that refugees were 3.5 times more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid than nonrefugees.

The analysis also confirmed that Russian refugees were a distinctive group within the refugee population. They were 17 times more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid than other refugees who were not Russian, whereas the non-Russian refugees were only 1.5 times more likely than the nonrefugees to be enrolled in Medicaid. After controlling for all other study variables, we found that Russian refugees were more likely to be women, to be diagnosed with an affective disorder, to be 45 years or older, and to be enrolled in Medicaid. They were less likely to have used mental health services in the past.

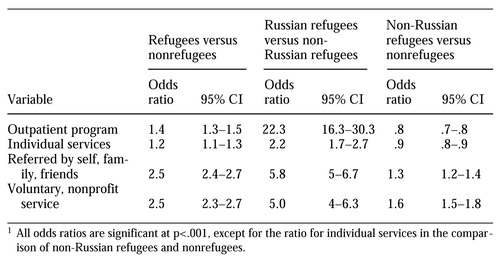

Table 4 shows that Russian refugees were significantly more likely to use outpatient services; to be referred by themselves, family, or friends; to have individual services; and to use mental health services in voluntary, not-for-profit facilities. The fact that the differences in all the service-use variables were statistically significant across three groupings could be due to the large sample size. Yet the sizes of the odds ratios differed considerably; they increased twofold or more for each variable when Russian refugees were compared with non-Russian refugees.

For example, the increase of the likelihood of outpatient services use was quite dramatic, from .8 for the comparison of non-Russian refugees and nonrefugees to 1.4 for the comparison of refugees and nonrefugees to 22.3 for the comparison of Russian refugees and non-Russian refugees. Thus it is reasonable to conclude that Russian refugees who were mental health services users had distinctive characteristics compared with all other users, including non-Russian refugees.

Discussion and conclusions

Our study findings suggest the emergence of a distinct group of Russian refugees who are users of mental health services. They are distinguished from non-Russian refugees and nonrefugees by both their demographic characteristics and their service utilization patterns. The typical Russian refugee who used mental health services was likely to be a depressed older woman who was using those services for the first time.

Previous studies have suggested that Russian refugee women are emotionally vulnerable to the stresses of living in a new environment (5,15). We also noted that Russian refugee women were more likely to use services than the men. This pattern is not surprising, as an earlier study found that Russian refugee women are more assimilated into the American culture than the men (5). Thus women might be more willing to overcome cultural barriers to seeking mental health services.

Consistent with past studies of other cultural and ethnic groups (7,16), Russian refugees who used mental health services were mainly referred either by themselves or by their friends and relatives. The small number of referrals made by the formal health and mental health service systems suggests that these populations have underused professional services. Members of cultural and ethnic minority groups tend to delay seeking mental health treatment; they use services only as the last resort, thus prolonging unnecessary suffering for both the users and their families (17). Still another possible explanation for the low number of referrals made by health and mental health services is that the existing service system has not yet recognized the Russian refugee population.

Russian refugees were more likely than the other groups in the study to use nonprofit agencies instead of public agencies. This pattern is understandable because public agencies, which are associated with the government, might not be perceived as trustworthy by persons from the former Soviet Union. However, an overwhelming proportion of our study sample was enrolled in Medicaid. Because public agencies are more likely to serve Medicaid populations, these agencies must be responsive to the needs of the refugee community.

It is important for service providers to develop trust and to build relationships through active outreach to the community. A number of strategies can be considered to engage refugee clienteles and to improve access to services. For example, bilingual services should be available. In addition, the development of trust could be enhanced by encouraging referrals from community leaders, such as rabbis in the Jewish community at large and in the Orthodox Jewish community in particular (18,19).

That the majority of the Russian refugees in this study were first-time service users could be explained by their recent arrival in this country. Service providers in areas where large numbers of Russian refugees reside must be educated about the special needs of this population. The majority of the Russian refugees in this study lived in New York City, primarily in the Bronx and Brooklyn. The fact that many Russian refugees are Jewish and that they are both ideologically and culturally different from the American Jewish population must be recognized (5). It has long been argued that mental health needs of the Jewish community in general are not adequately served in the United States (18,19).

In addition to better understanding the cultural and religious background of Russian refugees, mental health services must consider the traumatic environment from which this population came. Characteristics of this environment have included the chronic deprivation of human rights, oppression of religious freedom, and oppression of various cultural and ethnic groups. To more fully address past trauma, mental health services should be integrated into refugee resettlement programs.

This study represents one of the first attempts to describe the patterns of mental health services used by Russian refugees. However, due to the limitations of the data, the findings of this study should be applied only to those who have received services. In addition, the lack of other data, such as the size of the entire refugee population, prevented us from examining some important questions such as the prevalence rates of mental illness. Therefore, for refugees who are in need of health services, many questions remain unanswered.

Future research should explore the relationship between the length of stay in the United States and help-seeking behavior. The possibility of gender differences in willingness to seek help should be tested. Most important, research should continue to examine ways in which mental health services could improve the well-being of recently arrived refugees so that they can have a better life in the United States.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by a Faculty Research Awards Program grant and by grant P30-HD-32041 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and grant SBR-9512290 from the National Science Foundation to the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany, State University of New York. The authors thank Patricia Glynn, M.P.A., and Ruby Wang, Ph.D., for help with data management and statistical consultation and Burton Gummer, Ph.D., and Ronald Toseland, Ph.D., for comments on the manuscript.

Dr. Chow is assistant professor and Ms. Choi is a research assistant in the School of Social Welfare at the University at Albany, State University of New York, 135 Western Avenue, Albany, New York 12222 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Chow is also a faculty member at the Center for the Study of Issues in Public Mental Health at the New York State Office of Mental Health. Ms. Jaffee is assistant professor in the School of Social Work at Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York.

|

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of clients served by the New York State mental health system during a week in fall 1995 (N=151,008), by refugee status, in percentages1

|

Table 2.

Service use by clients served by the New York State mental health system during a week in fall 1995 (N=173,424), by refugee status, in percentages1

|

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) resulting from logistic regression of demographic and clinical variables (N=108,770), by refugee status1

|

Table 4.

Odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) resulting from logistic regression of service use variables (N=151,475), by refugee status1

1. Office of Refugee Resettlement: Refugee Resettlement Program. Report to the Congress, Fiscal Year 1995. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1995Google Scholar

2. Kohn R, Flaherty J, Levav I: Somatic symptoms among older Soviet immigrants: an exploratory study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 35:350-360, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Barankin T, Konstantareas MM, Bosset F: Adaption of recent Soviet Jewish immigrants and their children to Toronto. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 34:512-518, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Flaherty J, Kohn R, Golbin A, et al: Demoralization and social support in Soviet-Jewish immigrants to the United States. Comprehensive Psychiatry 27:149-158, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Birman D, Tyler F: Acculturation and alienation of Soviet Jewish refugees in the United States. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs 120:103-115, 1994Google Scholar

6. Akutsu PD, Snowden LR, Organista KC: Referral patterns in ethnic-specific and mainstream programs for ethnic minorities and whites. Journal of Counseling Psychology 48:56-64, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Hu T-W, Snowden LR, Jerrell JM, et al: Ethnic populations in public mental health: services choice and level of use. American Journal of Public Health 81:1429-1434, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Maynard C, Ehreth J, Cox GB, et al: Racial differences in the utilization of public mental health services in Washington State. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:411-424, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Snowden LR, Cheung FK: Use of inpatient mental health services by members of ethnic minority groups. American Psychologist 45:347-355, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Snowden LR, Hu T-W: Outpatient service use in minority-serving mental health programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:149-159, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Snowden LR, Hu T-W: Ethnic differences in mental health services use among the severely mentally ill. Journal of Community Psychology 25:235-247, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Takeuchi DT, Bui K-VT, Kim L: The referral of minority adolescents to community mental health centers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 34:153-154, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Takeuchi DT, Sue S, Yeh M: Return rates and outcomes from ethnicity-specific mental health programs in Los Angeles. American Journal of Public Health 85:638-643, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Stokes M, Davis C, Koch G: Categorical Data Analysis Using the SAS System. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1995Google Scholar

15. Garcia-Peltoniemi RE: Epidemiological perspectives, in Mental Health Services for Refugees. Pub no (ADM) 91-1824. Edited by Westermeyer J, Williams CL, Nguyen AN. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1991Google Scholar

16. Bushwald D, Klacsanzky G, Manson SM: Psychiatric disorders among recently-arrived Eastern Europeans seen through a US refugee counseling service. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 39:221-227, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Primm A, Lima B, Rowe C: Cultural and ethnic sensitivity, in Integrated Mental Health Services: Modern Community Psychiatry. Edited by Breakey W. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

18. Feinberg SS, Feinberg K: An assessment of the mental health needs of the Orthodox Jewish population of metropolitan New York. Journal of Jewish Communal Service 62:29-39, 1985Google Scholar

19. Slanger C: Orthodox rabbinic attitudes to mental health professionals and referral patterns. Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 31(1):22-32, 1996Google Scholar