A Randomized Controlled Study of Two Styles of Group Patient Education About Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The therapeutic specificity of patient education about schizophrenia was investigated in a randomized controlled study comparing the effects of two styles of group educational intervention. METHODS: Thirty-three adult inpatients with schizophrenia were assigned in a stratified random manner either to an experimental patient education group that used a didactic format to cover a range of topics on the characteristics and treatment of schizophrenia (N=16) or to a control group in which participants discussed their subjective experiences with schizophrenia and its treatment (N=17). Before and after the group interventions, participants responded to measures of knowledge about schizophrenia, insight into illness, and cognitions about medication intake. RESULTS: The two groups did not differ significantly in postintervention scores on measures. CONCLUSIONS: The benefits of patient education may not be due to specific active therapeutic educational ingredients but may be due instead to the presence of nonspecific treatment effects.

Several controlled outcome studies have provided patient education to individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia with the aim of studying the specific effects of the interventions. Some have reported substantial benefits from patient education, including improved compliance with the medication regimen (1,2,3,4,5), lower relapse rate (6), longer participation in aftercare programs (7), improved social functioning and quality of life (8), decreased negative symptoms (9), improved insight into illness (3,10), improved skills acquisition (11), improved attitudes toward medication intake (1,3,12,and better understanding of mental illness (4,9,10,13,14).

All of these studies, with three exceptions (2,3,15), have used waiting-list control groups, a strategy that does not permit the identification of the active therapeutic ingredients in the educational program nor the magnitude of nonspecific treatment effects. The three exceptions—all using control groups involving placebo activities—had conflicting results. The first reported a lack of significant differences in compliance between the education group and the control group (15). The second reported significant group differences in compliance immediately after the intervention but a lack of differences at follow-up one year later (2). The third study was the only one using an alternative control group that has supported the presence of specific and beneficial effects of patient education (3). However, the study participants were a mixed diagnostic group of inpatients with psychotic disorders, and only half of the sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Thus the study findings are subject to questions about the possible ramifications of the sample's diagnostic heterogeneity.

When studying the specific benefits of patient education about schizophrenia, researchers need to verify that observed group differences are indeed due to the educational intervention. Numerous alternative explanations for such effects exist. They include placebo effects that are conceptualized as nonspecific effects—features common to virtually any therapeutic intervention (16). Some examples of nonspecific effects are patients' expectations; their motivation to participate; the degree of attention from mental health professionals; the interpersonal support from other study participants; patients' opportunities to express and validate their concerns and questions about treatment; and their opportunities to observe positive modeling behaviors of group participants, to become part of a cohesive group, and to recognize that they are not alone in their experience of severe and chronic mental illness. The power of nonspecific effects has been studied extensively for psychosocial and biological treatments, leading to the conclusion that outcome research designs should implement credible but inert control conditions (17,18).

The goal of the study reported here was to identify the extent to which patient education about schizophrenia produces specific beneficial changes beyond the changes that would result from the presence of nonspecific factors alone. It compared outcomes for a didactic patient education group with those for a credible control group who participated in a discussion group.

Methods

Sample

Forty-two adult inpatients at a Midwestern state psychiatric hospital were referred by their treatment team to a structured didactic group education program on coping with schizophrenia. They were individually interviewed between February and July 1996 to assess their interest in participating in the study. Seven patients refused to participate, and two patients were excluded because they were at risk for elopement, suicide, or acting out. During the interview, the program, which was offered routinely at the facility, was described as an opportunity for patients to learn more about coping with their illness.

The 33 patients who agreed to participate gave their written consent and were assigned to the experimental didactic group condition (N=16) or the discussion group control condition (N=17), using a stratified randomization process that matched participants on educational level, sex, and race. Thirty-one patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, and two met criteria for schizoaffective disorder. The patients appeared to be well motivated to participate in a patient education program.

The participants included 14 women and 19 men. Eight were African American, and 25 were Caucasian. Most (N=29) were single. Their mean age was 36.4 years, with a range from 20 to 58 years. The average number of years of education was 12.3.

Data were collected on additional patient characteristics, including presence of a DSM-IV axis II secondary diagnosis, current score on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale, estimated full-scale IQ and abstraction quotient, length of current hospital stay, number of previous hospitalizations, history of noncompliance with a medication regimen, history of substance abuse, and history of legal difficulties.

Procedures

Two didactic groups and two discussion groups with about eight participants each met for one hour each weekday for three weeks, for a total of 15 sessions. The same seven group leaders were involved in leading both types of groups. The group leaders—six women and one man—included a psychologist, a behavioral clinician, a social worker, a psychiatric nurse, and three psychology doctoral candidates. Group leaders had an average of five years of experience in providing the patient education program, with a range from one to ten years.

Both the didactic groups and the discussion groups met at the hospital's learning center, and both followed the same sequence of topics on the same days. Two sets of groups, each with one didactic group and one discussion group, were offered over a six-month period. There was a four-month break between the first and second set to allow for further recruitment of study participants. In the first set, the didactic group met from 1 to 2 p.m. and the discussion group met from 2 to 3 p.m. In the second set, the discussion group met from 1 to 2 p.m. and the didactic group met from 2 to 3 p.m. All participants received a written outline indicating the topics that would be covered, the schedule, and the names of the coleaders.

The didactic group followed guidelines of a published manual on psychoeducation groups for patients with schizophrenia (19). The topics included diagnosis, prevalence, course, causes, prognosis, medication management, nonmedical treatments, stress factors, community resources, substance abuse, and legal issues. The manual emphasizes the need to understand early warning signs, monitor their occurrence and severity level, and develop relapse prevention plans that involve patients' support systems.

Although both study groups discussed the same topics, in the same order, and on the same day, their sessions differed in format. The discussion group leaders solicited an active exchange of participants' subjective experiences suggested by the topic. Group leaders did not volunteer any information unless requested specifically by a participant, which occurred briefly on very few occasions. The didactic group sessions integrated similar active discussions but also provided lectures, question-and-answer periods, and an array of media aids such as educational slides, videotapes, worksheets, and handouts.

Participants responded to several questionnaires before and after the group intervention. Pregroup measures included the Shipley Institute of Living Scale (20), which is an intelligence screening test that provides an estimated full-scale IQ and abstraction quotient, and a five-item questionnaire on which participants were asked to rate their expectations about satisfaction with the group experience and its potential benefits on a 5-point scale from "not at all" to "very much."

Three measures were completed by participants both before and after participating in the group intervention. Participants completed the Knowledge About Schizophrenia Questionnaire (KASQ), which includes 25 multiple-choice questions that measure knowledge about schizophrenia (21). The reliability and validity of the KASQ have been demonstrated (21). Participants also completed the Cognitions About Medication Intake (CAMI) questionnaire, which measures patients' negative beliefs about intake of medications (22). Patients rated their agreement with 24 statements about intake of medications on a 5-point scale ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree." An eight-item, multiple-choice questionnaire adapted as a self-report measure from the Schedule for Assessment of Insight (23) was used to determine the degree to which participants perceived themselves as mentally ill and in need of treatment.

After the group intervention, participants completed an anonymous questionnaire assessing their satisfaction with different aspects of the group experience and the degree of perceived helpfulness of the topics presented in the groups. The questionnaire included 15 items, each rated on a 9-point scale from 1, none, to 9, very much.

Results

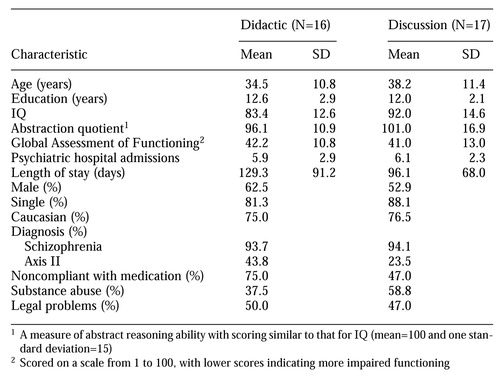

Initial equivalency of the two groups was assessed by a multivariate analysis of variance using patient characteristics measured as continuous variables; they included age, educational level, IQ, abstraction quotient, current GAF, number of previous hospitalizations, current length of stay, and level of expectations of upcoming group experience. Chi square tests were used to compare the groups on nominal variables such as marital status, presence of axis II diagnosis, past noncompliance with medication regimen, history of legal problems, and history of substance abuse. The results, shown in Table 1, indicated that the groups did not differ significantly on any of these variables. Furthermore, t tests showed nonsignificant group differences before the group intervention on the three dependent variables—scores on the KASQ, the CAMI, and the insight questionnaire.

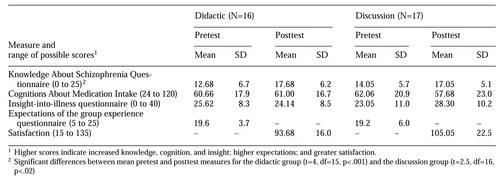

T tests for independent samples were used to compare posttest dependent measures of the effects of patient education for the two groups. No significant differences were found between the groups on the KASQ, the CAMI, the insight questionnaire, or the satisfaction questionnaire.

Paired t tests were then used to compare each group's pre- and posttest measures. Significant findings were noted for both groups only on one variable, the KASQ score. The didactic group gained an average of 5 points (t=4, df=15, p<.001). The discussion group gained an average of 3 points (t=2.5, df=16, p<.02). Table 2 presents the two groups' mean scores on dependent measures before and after the interventions.

To identify patient characteristics that were linked to favorable performance on the dependent measures, Pearson product-moment correlations were used for data for the entire sample. A significant association was found between education level and gaining at least 20 percent on the KASQ score (r=.49, p<.003) and between education level and a gain in insight into the illness (r=.35, p<.03). Furthermore, a decrease in negative cognitions about medication intake as measured by the CAMI was significantly associated with IQ (r=-.47, p<.017) and with gain in insight into the illness (r=-.52, p<.005).

In addition, scores on insight into the illness after the intervention were significantly associated with decreased negative cognitions about medication intake (r=-.65, p<.001) and increased knowledge about schizophrenia (r=.40, p<.02).

Discussion and conclusions

This study, which examined the efficacy of two styles of patient education, was not successful in separating the specific therapeutic effects of patient education from nonspecific effects. The experimental and control groups did not differ on their pretest or posttest measures. Furthermore, both groups made significant and similar gains in knowledge about schizophrenia, even though the patients in the control group received no direct information and no didactic interventions.

The results suggest that no discernable differences in outcome occur when the control condition is credible to patients and when it generates equally high expectations for therapeutic change, compared with the experimental condition. Such observations have been previously noted in psychotherapy and medical treatment outcome studies (24,25), and, more specifically, in a study of an educational intervention for relatives living with individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (26).

The study reported here attempted to equate the experiences of the experimental and control groups by matching groups on a number of patient and intervention variables and by keeping the therapist variables relatively constant. These efforts appear to have given both groups of patients similarly high levels of satisfaction. Although therapists' differential expectations of the two types of groups were not measured, there was an underlying expectation for the experimental group to excel on the dependent measures as a direct result of extensive educational efforts.

Similar negative findings have been noted in other controlled outcome studies of patient education about schizophrenia in which the control group implemented a recreational group experience (27) or used neutral discussions about the hospital and past military experiences (15). However, such negative results are not confined to actively controlled studies but have been documented in studies in which waiting-list control groups have been used to examine improvements in patient's knowledge, insight, or attitudes toward medication intake (14,28,29). Although these outcome studies differ markedly in many aspects, including the scope, content, intensity, and length of patient education, they share this study's findings of nonsignificant differences between the experimental and control groups.

However, findings from the current study should be perceived as preliminary and limited. Replication of this study should involve a larger sample and preferably two control groups—one engaged in a credible but neutral group activity and the other consisting of patients on a waiting list.

It is possible that this study's choice of discussion about the illness as the placebo for the control group was not as inert as intended. Patients may have gained information about the illness while observing others and listening to their peers. Additional learning processes outside of group sessions cannot be ruled out either. Participation in the discussion group may have motivated some individuals to seek additional information independently from other sources, such as a nurse or technician or the library. Such alternative explanations highlight the study's limitations and the need for additional rigorous empirical studies in this area.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ann Claveaux, M.A., Donna Cisco, C.C.S.W., and Sandra Rochford, R.N.

Dr. Ascher-Svanum is staff psychologist in the psychiatry service (116A), Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 1481 West Tenth Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 (e-mail, [email protected]). She is also clinical associate professor in the department of psychiatry at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis. At the time of the study, Mr. Whitesel was a research assistant at Larue Carter Hospital in Indianapolis. He is now a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients assigned to an experimental patient education group involving didactic sessions and a control group involving discussion

|

Table 2. Mean pretest and posttest scores on measures of the effects of patient education among patients in the didactic and discussion groups

1. Guimon J: The use of group programs to improve medication compliance in patients with chronic diseases. Patient Education and Counseling 26:189-193, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hornung P, Kieserg A, Feldman R, et al: Psychoeducational training for schizophrenic patients: background, procedure, and empirical findings. Patient Education and Counseling 29:257-268, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, et al: Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 312:345-349, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Robinson G, Gilbertson A, Litwack L: The effects of a psychiatric patient education to medication program on post-discharge compliance. Psychiatric Quarterly 58:113-118, 1986-87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Seltzer A, Roncari I, Garfinkel P: Effects of patient education on medication compliance. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 25:638-644, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rund B, Moe L, Sollien T, et al: The psychosis project: outcome and cost-effectiveness of a psychoeducational treatment programme for schizophrenic adolescents. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:211-218, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kinney H, Lindsey K: Understanding mental illness: a group approach to reduce readmissions. Journal of Applied Social Sciences 4:173-184, 1980Google Scholar

8. Atkinson J, Coia D, Gilmour H, et al: The impact of education groups for people with schizophrenia on social functioning and quality of life. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:199-204, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Goldman CR, Quinn FL: Effects of a patient education program in the treatment of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:282-286, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Macpherson R, Jerrom B, Hughes A: A controlled study of education about drug treatment in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:709-717, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Eckman T, Wirhing W, Marder S, et al: Technique for training schizophrenic patients in illness self-management: a controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1549-1555, 1992Link, Google Scholar

12. Hornung P, Holle R, Schulze Monking H, et al: Psychoedukative-psychotherapeutische behandlung von schizophrenen patienten und ihren bezugspersonen [Psychoeducational intervention of schizophrenic patients and their self-report]. Nervenartz 66:828-834, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

13. Goulet J, Lalonde P, Lavoie G, et al: Effets d'une education au traitement neuroleptique chez de jeunes psychotiques [Effects of a neuroleptic treatment teaching module among young patients with psychotic disorders.] Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 38:571-573, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Streicker SK, Amdur M, Dincin J: Educating patients about psychiatric medications: failure to enhance compliance. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 9(4):15-28, 1986Google Scholar

15. Boczkowski J, Zeichner A, DeSanto N: Neuroleptic compliance among schizophrenic outpatients: an intervention outcome report. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology 53:666-671, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. White L, Tusky B, Schwartz G (eds): Placebo Theory, Research, and Mechanisms. New York, Guillard, 1985Google Scholar

17. Roberts A, Kewman D, Mercier L, et al: The power of non-specific effects in healing: implications for psychosocial and biological treatments. Clinical Psychology Review 13:375-391, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Eysenck HJ: The outcome problems in psychotherapy: what have we learned? Behavior Research and Therapy 32:477-495, 1994Google Scholar

19. Ascher-Svanum H, Krause A: Psychoeducational Groups for Patients With Schizophrenia: A Guide for Practitioners. Gaithersburg, Md, Aspen, 1991Google Scholar

20. Shipley W: Shipley Institute of Living Scale. Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 1986Google Scholar

21. Ascher-Svanum H: Development and validation of a measure of patient's knowledge about schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 50:561-563, 1999Link, Google Scholar

22. Ascher-Svanum H, Waldo T: Development and validation of a measure of patient's negative cognitions about neuroleptics. Presented at the annual convention of the American Association of Applied and Preventive Psychology, San Diego, June 18-20, 1992Google Scholar

23. David AS: Insight and psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:798-808, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Gruenbaum A (ed): The Placebo Concept in Psychiatry and Medicine. Madison, Wisc, International Universities Press, 1993Google Scholar

25. Turner J, Gallimore R, Fox-Henning C: An annotated bibliography of placebo research (ms no. 2063.) JSAS Catalogue of Selected Documents in Psychology 10:2, 1980Google Scholar

26. Smith JV, Birchwood MJ: Specific and non-specific effects of educational intervention with families living with a schizophrenic relative. British Journal of Psychiatry 150:645-652, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hornung P, Buchkremer G, Franzen U: The efficacy of psychoeducational training in schizophrenic patients. Psychiatria Danubina 5:251-260, 1993Google Scholar

28. Jewart R: Patient education on the nature, course, and treatment of schizophrenia and its effects on patient knowledge, awareness of illness, and therapeutic compliance. Dissertation Abstracts International 48:1540A, 1987Google Scholar

29. McGill C, Falloon IR, Boyd JL, et al: Family educational intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:934-938, 1983Abstract, Google Scholar