Legal System Involvement and Costs for Persons in Treatment for Severe Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders were followed for three years to better understand how they are involved with the legal system and to identify factors associated with different kinds of involvement. METHODS: Data came from a three-year study of 203 persons enrolled in specialized treatment for dual disorders. Cost and utilization data were collected from multiple data sources, including police, sheriffs and deputies, officers of the court, public defenders, prosecutors, private attorneys, local and county jails, state prisons, and paid legal guardians. RESULTS: Over three years 169 participants (83 percent) had contact with the legal system, and 90 (44 percent) were arrested at least once. Participants were four times more likely to have encounters with the legal system that did not result in arrest than they were to be arrested. Costs associated with nonarrest encounters were significantly less than costs associated with arrests. Mean costs per person associated with an arrest were $2,295, and mean costs associated with a nonarrest encounter were $385. Combined three-year costs averaged $2,680 per person. Arrests and incarcerations declined over time. Continued substance use and unstable housing were associated with a greater likelihood of arrest. Poor treatment engagement was associated with multiple arrests. Men were more likely to be arrested, and women were more likely to be the victims of crime. CONCLUSIONS: Effective treatment of substance use among persons with mental illness appears to reduce arrests and incarcerations but not the frequency of nonarrest encounters. Stable housing may also reduce the likelihood and number of arrests.

Persons with severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, are at greater risk for arrest and incarceration than the general population (1,2). Abuse of alcohol or other drugs further increases the likelihood of involvement in the legal system (3,4).

Despite the more frequent contact with criminal justice authorities by persons with mental illness, research does not support the widely held notion that this group represents a significant threat to others. Most offenses are minor, and the association between violence and mental illness is weak (5,6). However, a recent study suggests that substance abuse increases the likelihood of violent behavior among persons with mental illness (7). Some studies indicate that increased vulnerability and stigma may contribute significantly to higher arrest rates in this group (2,8).

Contact between persons with serious mental illness and the legal system extends beyond activities related to illegal behavior. It is increasingly recognized that persons with serious mental illness have high rates of physical and sexual victimization (9,10). In some locations, jails and prisons substitute for distant or overburdened mental health facilities. Much has been written about persons with mental illness who go untreated in urban correctional facilities (11,12), but the problem is not limited to cities. Sullivan and Spritzer (13) documented systematic use of jails as temporary holding facilities for persons with serious mental illness in rural areas. Legal processes associated with involuntary commitment and guardianship, police assistance in psychiatric emergencies, and the role of law enforcement officials in transporting persons with serious mental illness to treatment facilities may also contribute to costs incurred by the legal system (14).

Despite the extensive contact that persons with serious mental illness have with police, courts, corrections facilities, probation and parole officers, and legal advocates, the costs of such contact have been difficult to measure, and factors contributing to such costs remain poorly understood. Better information about contacts and costs would help identify problems and might suggest policy interventions that could improve the lives of persons with serious mental illness and the legal system's efficiency.

In this study, we used data from a more comprehensive cost-effectiveness study that examined social costs incurred by patients with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance use disorders who were in assertive community treatment and standard case management. The study reported here examined costs of involvement in the legal system by this group and explored factors associated with arrests and other types of encounters with the legal system.

Previous studies have identified several correlates of police encounters among persons with serious mental illness. Both substance abuse and homelessness are associated with high arrest and incarceration rates (15,16). Men are more likely than women to be arrested (5); young adults have higher arrest rates than older adults (3). Persons with serious mental illness who live in urban areas appear to be at greater risk of arrest and incarceration than those in rural areas (3) and may also be at greater risk of victimization (17). The contribution to arrest or incarceration made by clinical factors, such as diagnosis, symptoms, and aggressiveness, is not well established.

Because most studies have focused on arrest and incarceration rates or on criminal behavior, relatively little is known about the frequency and cost of encounters not resulting in arrest. Some empirical evidence suggests that encounters that do not result in arrest are much more frequent than those that do (18). Police often note that because of the frequency of these encounters, they absorb significant amounts of time. Furthermore, despite the relative frequency of civil actions, such as lawsuits, guardianship activities, and involuntary hospitalizations, costs associated with civil actions have been ignored by most researchers.

The impact of treatment on the involvement of persons with mental illness with the legal system is ambiguous. Contact with the legal system is often seen as a result of inadequate treatment. Interventions such as assertive community treatment, which provide services to clients in natural settings, would seem to reduce encounters by substituting treatment providers for police in crisis response situations and by reducing the frequency of behaviors that lead to legal intervention, such as public disturbances. However, Wolff and associates (18) found a high one-year rate of involvement in the legal system among a sample of persons with serious mental illness who were receiving assertive community treatment. Some investigators have suggested that assertive community treatment reduces encounters with the legal system (19), some have found no effect (20), and others have observed increases in encounters (21).

Attempts to measure the frequency and cost of legal system encounters by persons with serious mental illness have been hampered by several problems. Many studies have relied on self-reported encounters, which may underestimate involvement. Few studies have measured the cost of services provided by all elements of the legal system, raising questions about the accuracy of total cost estimates. There are almost no data on the involvement in the legal system of persons with mental illness for a period longer than one year. Finally, most studies have been conducted in cities. Although crime may be more common there, it is also important to understand the characteristics of persons with serious mental illness involved with the legal system in rural areas.

In this study we went beyond these limitations by using an extensive, multisource system for tracking encounters for three and a half years and by carefully measuring the costs of each legal system component during the final three years of this period.

Our goals were to present a more complete picture of how persons with dual disorders are involved with the legal system, to identify factors associated with varieties of involvement, and to clarify the implications of these findings for mental health policy.

Methods

Data used in this analysis are from the New Hampshire dual disorder treatment study. Clinical and functional outcomes, as well as a cost-effectiveness analysis, are reported elsewhere (22,23). The cost-effectiveness analysis reported only total legal costs. This paper examines legal system involvement and its correlates in greater detail.

Sample

Study participants were selected from seven of New Hampshire's ten mental health catchment areas. Two of these areas were urban, centered around cities with populations between 100,000 and 150,000; the remaining five were predominantly rural, with towns of 25,000 persons or less. Participants were eligible for the study if they had a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder and a DSM-III-R diagnosis of an active substance use disorder within the past six months, with no additional severe medical conditions or mental retardation. Participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 60 years and be willing to provide written informed consent to participate in the study.

Of the 306 persons who were initially screened, 223 were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to assertive community treatment or standard case management. Both programs provided enhanced community-based treatment in the context of a highly rated public mental health system (24). A total of 166 participants (74 percent) were male, and 215 (96 percent) were from white nonminority groups. A total of 136 participants (61 percent) had never been married, 140 (63 percent) had at least a high school education, and 183 (82 percent) were unemployed. The mean±SD age at study entry was 34±8.5 years.

A total of 120 participants (54 percent) were diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Fifty (23 percent) had a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and the remainder (53 participants, or 24 percent) met criteria for bipolar disorder. All participants had a substance use disorder; 163 (73 percent) had an alcohol use disorder, and 94 (42 percent) had a drug use disorder, primarily cannabis or cocaine.

Over the study period (1989 to 1993), 20 participants were lost to follow-up. Of these, 11 refused to continue the study, seven died, and two moved to other states and could not be located for subsequent interviews. Among the remaining 203 participants, those enrolled in standard case management and assertive community treatment did not differ significantly in the number of legal system encounters during the six months before study entry or on any criteria for study entry. A more detailed description of sample selection has been published elsewhere (22).

Legal system encounters were tracked for three and a half years, beginning six months before participants were randomly assigned to the treatment groups and continuing for three years afterward. Costs were computed only for the three years after randomization. We were unable to collect comprehensive treatment cost data on ten of the 203 participants who completed the study (five participants from each treatment group). These participants received significant amounts of treatment from an out-of-state provider for one or more of the six-month measurement periods, preventing us from accurately assessing mental health treatment costs.

Measurement procedures

We measured all legal system costs associated with the study participants. The costs of receiving a report, investigating, adjudicating, and carrying out the sentence associated with a crime were included; however, personal costs associated with criminal victimization, such as the value of items stolen or income lost due to an injury, were excluded. All services provided by police, sheriffs and deputies, officers of the court, public defenders, prosecutors, private attorneys, local and county jails, state prisons, and paid legal guardians were included in our analysis. Medical records at the state psychiatric hospital were used to document involuntary commitment hearings in probate court because we were denied access to records. Lack of access to probate court records also prevented accurate measurement of divorce and child custody proceedings.

With each participant's written consent, data were collected from a statewide registry of arrests and from records maintained by local police, courts, jails, probation and parole offices, public guardians, state hospitals, and prisons. Reports from participants, family members, and case managers were also used to identify possible encounters with the legal system that occurred outside the state or that were not identified through initial record reviews. We then attempted to verify these self-reports with additional record reviews.

To determine unit costs, we examined expenditures and management information of representative police departments, courts, jails, prisons, an office of public guardianship, public prosecutors and defenders, private attorneys, and probation and parole offices. Time estimates for various types of court appearances were based on a combination of court records and interviews with court personnel. Police time was measured from police activity logs. Costs were determined for appropriate production units such as cost per hour of direct police service, cost per day of incarceration, cost per month of parole supervision at each of three levels of intensity, and so forth. When appropriate, expenditures were adjusted to include costs of operation, such as depreciated building space or vehicles purchased through another department.

We used an episode approach to allocate costs to time periods. All legal costs were associated with a triggering event, such as an arrest; costs were attributed to the period in which that event occurred. For example, for a person convicted because of an event occurring in the six months before the study period, all costs associated with that event (court appearances, legal representation, and imprisonment) were attributed to the baseline period. If a participant was arrested near the end of the study, all subsequent costs (discounted by 3 percent because they were incurred at a later time) were included in the study period.

Analytic approach

We calculated total legal system encounters and costs. Costs related to arrests and to encounters that did not result in arrests were examined separately because they represent qualitatively different events. Little is known about costs of encounters not resulting in arrest because they are seldom included in cost analyses.

Episode counts and cost distributions were bimodal, with several participants having no episodes and several having large numbers of encounters. We used both parametric statistics (t tests with log-transformed data) and nonparametric statistics (Mann-Whitney U tests) to compare participants who received assertive community treatment and standard case management. Analyses were repeated with data for patients with extremely high scores excluded from the analysis.

To explore factors related to legal system encounters over the three years after participants were randomly assigned to a treatment group, we used three logistic regression models with similar independent variables and with three dichotomous dependent variables: ever arrested versus never arrested, arrested more than once versus arrested once or never arrested, and having three or more encounters not leading to arrest versus having fewer than three. These classifications were adopted after examining distributional patterns of the continuous variables from which they were derived. In their continuous form, arrests and nonarrest encounters were skewed, making a categorical transformation appropriate. A different grouping was used for multiple nonarrest encounters (more than three encounters) than for arrest encounters (more than one arrest) to reflect the relatively greater frequency of nonarrest encounters than encounters that ended in arrest.

The models included variables that have been associated in the literature with legal system involvement or that were of theoretical importance (for example, housing instability). Independent variables included age, gender, diagnosis (schizophrenia spectrum versus bipolar disorder), urban or rural residence, treatment assignment (assertive community treatment versus standard case management), stage of substance abuse treatment at the beginning of the study (25), a cumulative measure of time spent in various stages of substance abuse treatment over the course of the study (stage of treatment multiplied by the amount of time spent in that stage), three-year inpatient and outpatient treatment costs, a variable indicating the number of six-month periods in which the participant reported physically attacking someone, the number of residential moves (excluding hospitalizations) over three years, and a variable indicating that the participant lived in unsupervised housing for more than one year.

Results

Contact with the legal system was common among the 203 study participants. A total of 169 of the persons enrolled in the study (83 percent) had an encounter with the legal system during the three-year period after they were randomly assigned to a treatment group. More than half of these persons were arrested at least once.

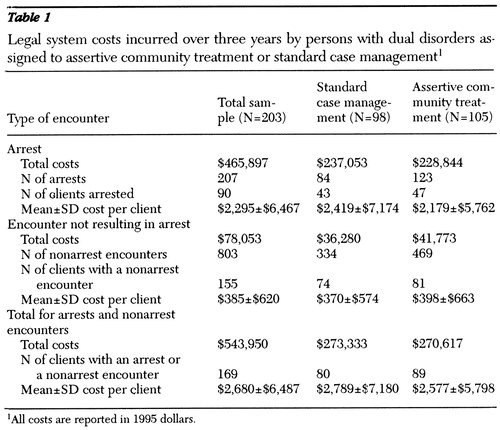

As Table 1 shows, the three-year cost of all legal system encounters by the study sample was $543,950, approximately 2 percent of the total social costs of $23,353,274 associated with the study participants (23). Participants were almost four times more likely to have an encounter not resulting in arrest than to be arrested, but arrests were far more costly, accounting for 85.6 percent of total legal system costs.

Participants in assertive community treatment and those in standard case management did not differ significantly in costs or encounters. None of the Mann-Whitney U test comparisons for arrests, arrest costs, nonarrest encounters, and costs for nonarrest encounters indicated a significant difference. T tests with log-transformed variables and with outliers removed also failed to detect significant differences between participants in assertive community treatment and those receiving standard case management.

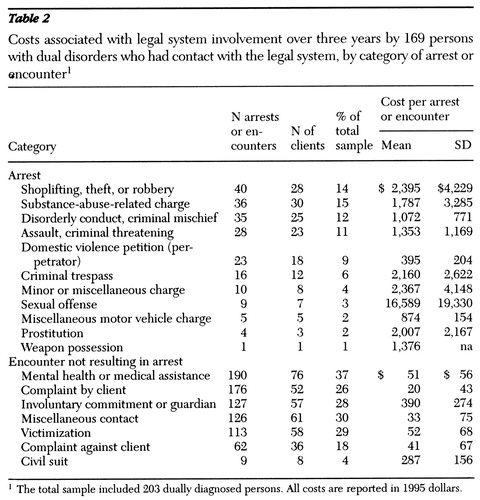

A wide variety of types of encounters with the legal system occurred. Table 2 shows the number of encounters and the number of participants with encounters in 11 arrest categories and seven categories of encounters not resulting in arrest, plus the average costs associated with each. Nonarrest encounters were particularly diverse, which led to a rather large miscellaneous category.

Costs associated with specific types of arrest and nonarrest encounters varied. Sexual offenses, such as rape or public exposure, were infrequent but costly, due primarily to lengthy prison sentences. Although more frequent than arrests, encounters that did not result in arrest, such as complaints filed by or against study participants and medical assistance received, were the least costly.

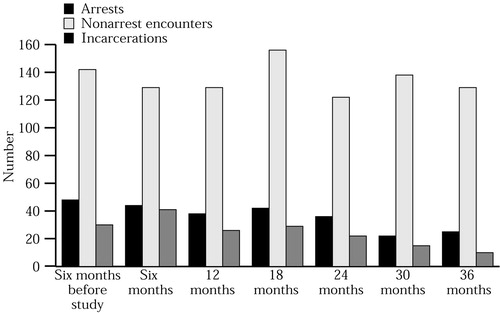

As shown in Figure 1, repeated-measures analysis of variance indicated that the number of arrests in each six-month period declined over the study period, dropping from 48 arrests for the entire sample in the six months before study entry to 25 arrests in the final six-month period (F=2.40, df=6,196, p=.029). The number of incarcerations also declined, from 23 during the baseline period to eight in the final period (F=3.50, df= 6,196, p=.003). A total of 142 encounters not resulting in arrest were recorded for the baseline period, and 129 encounters were recorded in the last period, not a statistically significant decrease.

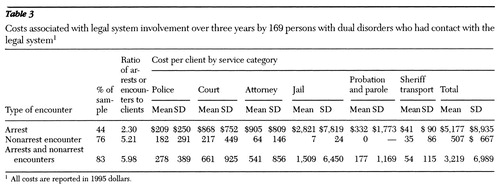

Table 3 outlines sources of legal system costs for persons who had contacts with the legal system. Although relatively infrequent, jailings and imprisonments accounted for more than half of arrest costs (55 percent). Courts and police accounted for the largest proportion of costs for nonarrest encounters—43 percent and 36 percent, respectively. Cost for legal episodes varied widely between individuals.

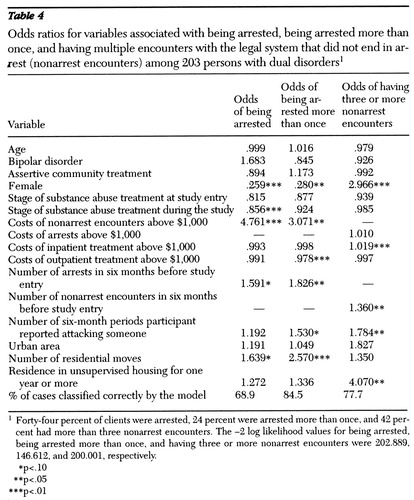

Factors contributing to the likelihood of any arrest, of multiple arrests, or of multiple nonarrest contacts are shown in Table 4. The odds of being arrested were higher for men, for persons in the earlier stages of substance abuse recovery, for those who had higher legal costs associated with nonarrest encounters, and for persons who changed residences more frequently. A trend toward greater likelihood of arrest for those with more arrests during the six months before study entry was also noted (p=.08).

Gender and costs for nonarrest encounters were also significant predictors of multiple arrests. Arrests in the baseline period and number of residential moves were stronger predictors of multiple arrests than of the probability of any arrest. Lower outpatient treatment costs and more frequent physical attacks on others were significant predictors of multiple arrests but not of the likelihood of any arrest.

In the third logistic regression model, which assessed factors associated with multiple nonarrest encounters, gender effects were reversed. Women were more likely than men to be involved in multiple nonarrest contacts. This finding appears to have been due to women's greater likelihood of being victimized compared with men (χ2= 8.40, df=1, p=.004). Higher inpatient treatment costs, more nonarrest contacts during the six months before study entry, and more frequent attacks on others were associated with greater odds of having multiple nonarrest contacts. Persons who lived in unsupervised housing for a year or more were four times more likely to have multiple nonarrest contacts with the legal system than were those who spent less time in such settings.

Although the urban-rural distinction was not associated with being arrested or with having multiple nonarrest encounters, it seemed to be associated with the type of encounter. Persons in urban areas were more likely to file a complaint with police (χ2=10.14, df=1, p=.002) and to be victims of crimes (χ2=9.66, df= 1, p=.002) than those in less densely populated areas. Persons living in rural areas were more likely to have complaints filed against them than their urban-dwelling counterparts (χ2=3.91, df=1, p=.05).

Discussion

Even among participants enrolled in state-of-the-art treatment programs, arrests and other encounters with the legal system are regular occurrences for persons with dual disorders. This study found that the cost of these encounters varied widely by type of encounter. Informal encounters that do not end in arrest, by far the most frequent category of involvement, were usually inexpensive. Most costly were the small number of cases in which participants were convicted of a serious offense such as rape or aggravated assault and given a lengthy prison sentence.

Study participants who were arrested fit a profile different from those with multiple encounters not resulting in arrest. Persons with many nonarrest encounters had a history of such contacts, were likely to be women, and tended to live in unsupervised housing. Compared with those who had few contacts with the legal system, they received more inpatient treatment and reported being violent more often. The greater frequency of nonarrest encounters among women appeared to result from their greater likelihood of being crime victims compared with men. Unlike men, whose legal system involvement appeared to follow the pattern observed in homeless populations—frequent arrests, substance abuse, housing instability, and tenuous engagement in treatment—women with multiple encounters with the legal system appeared to be relatively well engaged in treatment and living independently in unsupervised housing.

Our findings support the contention that effective treatment of persons with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance use disorders can reduce some legal system costs. Both arrests and incarcerations declined over time. Given the brief period for which data were available before participants entered the study (six months) and the absence of an untreated control group, we cannot reject with complete confidence the hypothesis that the decline of arrests and incarcerations was due to a natural regression to more typical levels from an elevated level of involvement in the legal system at study entry. However, the association between lower outpatient costs, which we interpret as an indicator of poor treatment engagement, and multiple arrests suggests a more direct connection between treatment and arrests. Interestingly, this relationship did not hold for encounters that did not end in arrest.

We believe these data are among the most comprehensive and valid available on legal system costs for persons with dual disorders. They capture the majority of legal system activity associated with the study participants. However, the data probably underestimate the frequency of domestic violence perpetrated by participants, and therefore the costs to the legal system. The underestimation is due to the fact that such reports are typically filed under the victim's name rather than the assailant's, which hampered case identification. We suspect that this inability to identify some cases had only a small impact on our cost estimates overall.

A standard, but nonetheless important, caveat is that law enforcement and civil commitment practices in New Hampshire may differ from those in other areas. However, we were unable to identify specific examples of any practices that were unique to the state.

Conclusions

For individuals who have serious mental illness, stable supervised housing and effective treatment of substance abuse appear to reduce their involvement in the legal system and thus the associated costs. Given the relatively high cost of treatment and the comparatively low cost of involvement in the legal system, lowering legal system costs is not a sufficient rationale for undertaking intensive integrated treatment for dual disorders. Rather, reducing involvement in the legal system by persons with serious mental illness is an important by-product of the improved quality of life that persons with dual disorders experience when they are able to reduce or eliminate substance use, which benefits both these individuals and society.

Mental health treatment providers can reduce arrests by making substance abuse an important focus of treatment and by increasing their efforts to engage reluctant clients in treatment. Working with law enforcement officials and with clients to reduce the likelihood of victimization and treat its consequences, particularly among women, should also be a high priority.

The question of which costs should reasonably be included in a cost-effectiveness analysis is particularly difficult for persons with conditions such as comorbid serious mental illness and a substance use disorder because these conditions are often associated with social costs in addition to treatment. This study suggests that although costs associated with legal system involvement of persons with dual disorders represent a small portion of total social costs, measurement and analysis of legal system costs can provide useful information for treatment and policy planning. However, the relatively small proportion of costs associated with encounters not resulting in arrests may not justify the investment of substantial research resources in the precise measurement of such costs.

This study provides further evidence that persons with mental disorders, even those receiving high-quality treatment and those living in predominately rural areas, have a great deal of contact with law enforcement officials. Previous studies suggest that some of this contact is related to stigma and thus is inappropriate. Although this may be true in some cases, in many instances, such as serious criminal behavior or criminal victimization, the legal system is probably the appropriate point of first contact. However, police and others in the legal system must be equipped to work effectively with persons who have dual disorders and with their treatment providers.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants MH-00839, MH-46072, and MH-47567 from the National Institute of Mental Health, by grant AA-08341 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and by the New Hampshire Division of Mental Health and Developmental Services.

The authors are affiliated with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center and with Dartmouth Medical School. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association held November 9-13, 1997, in Indianapolis. Address correspondence to Dr. Clark at Dartmouth Medical School, Department of Community and Family Medicine, Strasenburgh 7250, Hanover, New Hampshire 03755-3862 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Arrests, encounters with the legal system not resulting in arrests, and incarcerations among 203 persons with dual disorders six months before the study and in six-month periods over three years

|

Table 1. Legal system costs incurred over three years by persons with dual disorders assigned to assertive community treatment or standard case management 1

1 All costs are reported in 1995 dollars.

|

Table 2. Costs associated with legal system involvement over three years by 169 persons with dual disorders who had contact with the legal system, by category of arrest or encounter 1

1 The total sample included 203 dually diagnosed persons. All costs are reported in 1995 dollars.

|

Table 3. Costs associated with legal system involvement over three years by 169 persons with dual disorders who had contact with the legal system 1

1 All costs are reported in 1995 dollars.

|

Table 4. Odds ratios for variables associated with being arrested, being arrested more than once, and having multiple encounters with the legal system that did not end in arrest (nonarrest encounters) among 203 persons with dual disorders 1

1 Forty-four percent of clients were arrested, 24 percent were arrested more than once, and 42 percent had more than three nonarrest encounters. The -2 log likelihood values for being arrested, being arrested more than once, and having three or more nonarrest encounters were 202.889, 146.612, and 200.001, respectively.

* p<.10

** p<.05

*** p<.01

1. McFarland BH, Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, et al: Chronic mental illness and the criminal justice system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:718-723, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Teplin LA: Criminalizing mental disorder: the comparative arrest rate of the mentally ill. American Psychologist 39:794-803, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Holcomb WR, Ahr PR: Arrest rates among young adult psychiatric patients treated in inpatient and outpatient settings. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:52-57, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Abram KM, Teplin LA: Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees. American Psychologist 46:1036-1045, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fischer PJ: Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:46-51, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Teplin LA: The criminality of the mentally ill: a dangerous misconception. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:593-599, 1985Link, Google Scholar

7. Stedman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393-404, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Robertson G: Arrest patterns among mentally disordered offenders. British Journal of Psychiatry 153:313-316, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Carmen EH, Rieker PP, Mills T: Victims of violence and psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:378-383, 1984Link, Google Scholar

10. Jacobson A, Richardson B: Assault experiences of 100 psychiatric inpatients: evidence of the need for routine inquiry. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:908-913, 1987Link, Google Scholar

11. Lamb HR, Grant RW: The mentally ill in an urban county jail. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:17-22, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Belcher JR: Are jails replacing the mental health system for the homeless mentally ill? Community Mental Health Journal 24:185-195, 1988Google Scholar

13. Sullivan G, Spritzer K: The criminalization of persons with serious mental illness living in rural areas. Journal of Rural Health 13:6-13, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK, et al: Measuring resource use in economic evaluations: determining the social costs of mental illness. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:32-41, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Solomon PL, Draine JN, Marcenko MO, et al: Homelessness in a mentally ill urban jail population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:169-171, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Martell DA, Rosner R, Harmon RB: Base-rate estimates of criminal behavior by homeless mentally ill persons in New York City. Psychiatric Services 46:596-600, 1995Link, Google Scholar

17. Sampson RJ, Castellano TC: Economic inequality and personal victimisation: an area perspective. British Journal of Criminology 22:363-385, 1982Google Scholar

18. Wolff N, Diamond RJ, Helminiak TW: A new look at an old issue: people with mental illness and the law enforcement system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:152-165, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bond GR, Witheridge TF, Dincin J, et al: Assertive community treatment for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals in a large city: a controlled study. American Journal of Community Psychology 18:865-891, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Solomon P, Draine J, Meyerson A: Jail recidivism and receipt of community mental health services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:793-797, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

21. McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen L, et al: A multisite study of client outcomes in assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services 46:696-701, 1995Link, Google Scholar

22. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, et al: A clinical trial of assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 64:201-215, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK, et al: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment versus standard case management for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Health Services Research 33:1283-1306, 1998Google Scholar

24. Torrey EF, Erdman K, Wolfe SM, et al: Care of the Seriously Mentally Ill: A Rating of State Programs. Washington, DC, Public Citizen Health Research Group and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1990Google Scholar

25. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Burton HL, et al: A scale for assessing the stage of substance abuse treatment in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:762-767, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar