Characteristics of Nonresponders to a Patient Satisfaction Survey at Discharge From Psychiatric Hospitals

Abstract

The study compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated in the 31 psychiatric hospitals in Japan who did and did not return a satisfaction survey at discharge. Of the 471 patients discharged in a one-month period, 364 agreed to participate. A total of 235 turned in completed forms, 91 turned in incomplete forms, and 38 did not return the form. The latter two groups were defined as nonresponders. Nonresponders were significantly older than responders, but no significant differences were found between the two groups in diagnosis and other demographic characteristics. Responders and incomplete responders had significantly higher scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale than those who did not return the survey.

Recent movements to "get closer to the customers" cannot be ignored, even in health care services, and patient satisfaction is recognized as an important indicator of the quality of care (1). Participation in consumer satisfaction surveys is voluntary, and some people choose not to participate. In fact, a major limitation of such studies is the large number of refusals (2), and response rates are usually low (3). Thus it is doubtful whether responders are representative of the total population, and it is tempting to say that nonresponders are more likely to be less satisfied with services than responders.

We conducted the first study in Japan of patient satisfaction at discharge from psychiatric hospitals and examined the characteristics of nonresponders. We hypothesized that nonresponders would be older than responders and that nonresponders would have a lower level of functioning, as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning scale.

Methods

This study was the first multicenter patient satisfaction survey of patients discharged from psychiatric hospitals in Japan. Patients were informed that participation was voluntary and that their responses to the questionnaire would be analyzed by researchers, not by hospital staff. Both voluntarily and involuntarily committed patients were asked to participate. To ensure confidentiality, participants did not sign the questionnaire and sealed the mailing envelopes themselves. The questionnaires were mailed from each facility to the research team. Each patient's questionnaire had a separate number, which allowed it to be matched to a form on which the patient's psychiatrist submitted sociodemographic and diagnostic information to the research team.

The questionnaire consisted of eight items in four sections: overall satisfaction with psychiatric care (one item); satisfaction with the professional skills and behavior of psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, and clerks (four items); satisfaction with procedures at admission and during hospitalization related to informed consent about treatment (two items); and satisfaction with hotel-like aspects of the hospital, such as cleanliness (one item). All items were rated on a 4-point scale according to the degree of satisfaction, from 1, very poor, to 4, very good.

Of 471 patients consecutively discharged from the 31 psychiatric hospitals in Japan between August 10 and September 10, 1997, we excluded 14 patients with mental retardation (3 percent), 33 patients with senile dementia (7 percent), and 48 patients who developed physical diseases and were transferred to other hospitals (10 percent). Twelve patients (3.2 percent) refused to participate.

Of the 364 patients who agreed to fill out the questionnaire, 235 patients completed it and 129 failed to complete it. The nonresponders included 38 patients who did not return the questionnaire and 91 who skipped some of the items. We categorized the incomplete responders as nonresponders in this study, because it was felt that failure to complete an item might reflect dissatisfaction. Thus the response rate was 65 percent.

We first compared characteristics of the responders and nonresponders. We then divided the nonresponders into two groups and analyzed differences between the 38 who did not return the survey, the 91 who did not complete all the items, and the 235 responders. Finally, we compared responders and incomplete responders on each item of the questionnaire.

Psychiatrists provided information on the sociodemographic and psychiatric characteristics of study participants, including gender, age, education, insurance, ICD-10 diagnosis, the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score (4), number of admissions, length of stay, type of treatment ward, and type of commitment.

For comparisons between responders and nonresponders, we used the chi square test, univariate analysis of variance, and the Mann-Whitney U test. For multiple comparisons between responders, incomplete responders, and nonresponders, we used the Scheffé test.

Results

The mean±SD age of the 364 subjects was 43.4±15 years. Seventy-five patients (21 percent) were under age 30; 80 (22 percent) were between age 30 and 39; 94 (26 percent) were between age 40 and 49; 54 (15 percent) were between age 50 and 59; and 61 (17 percent) were 60 or older.

The nonresponders—those who did not return the survey and those who returned it incomplete—were significantly older than the responders (46.6±15.5 versus 41.6±14.5 years; F=9.27, df=1,359, p<.01). A total of 87 nonresponders were hospitalized on a locked ward, compared with 132 responders (67 percent versus 56 percent; χ2=4.42, df=1, p<.05). No other significant differences were found between the two groups.

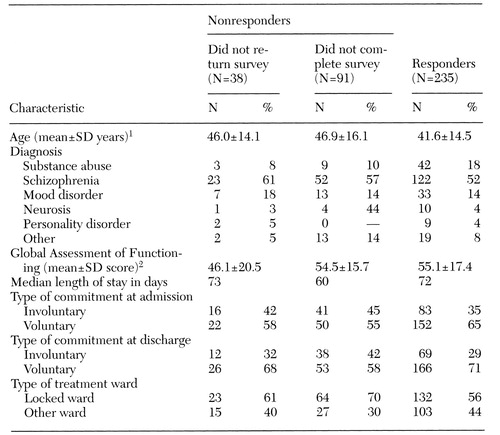

As Table 1 shows, compared with patients who returned the survey incomplete, responders were significantly younger. No significant correlation was noted between age and GAF score. The mean GAF score of those who did not return the survey was significantly lower than the scores of both the incomplete responders and responders.

We examined the questionnaire items that were not answered by the 91 incomplete responders. The items most frequently left blank related to satisfaction with the professional skills and behavior of social workers (12 patients, or 13 percent), followed by items on informed consent (seven patients, or 7 percent) and items on the professional skills and behavior of nurses (five patients, or 6 percent).

Discussion

Sampling bias is the major problem in patient satisfaction studies; research has found that patients who are satisfied are more likely to participate in satisfaction surveys than those who are dissatisfied (2). In this study, nonresponders were not patients who refused to participate in the survey but those who agreed to participate and did not return the questionnaire or complete all the items.

Our finding that nonresponders were older than responders suggests that older patients may not be well represented in satisfaction surveys. If we assume that nonresponders were more dissatisfied than responders of all ages, it appears that the older patients who responded were those who were most satisfied. Thus the results would tend to be biased toward younger and more satisfied patients.

Compared with responders, a greater proportion of nonresponders were hospitalized on a locked ward. Although participation in the study was voluntary, patients who were on a locked ward might perceive participation as a kind of coercion even at discharge, when their symptoms were improved. Thus they might agree to participate but then fail to submit the questionnaire.

Interestingly, incomplete responders were similar to those who did not return the survey in age and type of treatment ward (locked or other ward); however, incomplete responders were similar to responders in GAF score. Incomplete responders often skipped the items about the professional skills and behavior of social workers, clerks, and nurses and about the procedures used at admission and during hospitalization with regard to informed consent for treatment. It is possible that incomplete responders who were dissatisfied with certain aspects of their care chose to leave specific items blank to show their dissatisfaction indirectly.

Patients who agreed to participate in the study but did not return the questionnaire had significantly lower GAF scores at discharge than incomplete responders and responders. Thus patients with lower functioning were less likely to return the questionnaire. One reason might be that these patients failed to understand the instructions about completing the questionnaire.

The study was limited by the small size of the nonresponder group. Also, we obtained no satisfaction data for 12 patients who refused to enter the study and 95 patients who were excluded because they were judged incompetent to participate due to mental retardation or dementia.

Our results highlight the need for further studies on how patients' functioning and the type of ward they are treated on might affect satisfaction. As noted by Cleary and McNeil (1), higher satisfaction may be a result of better patient-physician interactions. Patients' poor functioning and time spent in seclusion may disrupt such interactions.

This preliminary study examined characteristics of patients who provide "silent responses" to satisfaction studies. To improve patient care, future studies should focus on minimizing nonresponse rates.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (grant 09770761) from the Japan Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture.

Dr. Ito is affiliated with the department of health care economics at the National Institute of Health Services Management, 1-23-1 Toyama, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-0052, Japan (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Shingai is with Narimasu Kousei Hospital in Tokyo. Dr. Yamazumi is with Hanazono Hospital in Yamanashi. Dr. Sawa is with Sawa Hospital in Osaka. Dr. Iwasaki is with the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 364 patients discharged from Japanese psychiatric hospitals, by whether they did not return a satisfaction survey, failed to complete some items, or completed the survey

1 F=4.67, df=2,358, p<.01, for the difference between the three groups; using the Scheffé test, significant difference (p<.05) between incomplete responders and responders

2 F=4.42, df=2,353, p<.05, for the difference between the three groups; using the Scheffé test, significant difference (p<.05) between those who did not return the survey and incomplete responders and between those who did not return the survey and responders

1. Cleary PD, McNeil BJ: Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality care. Inquiry 25:25-36, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lebow J: Consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment. Psychological Bulletin 91:244-259, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ruggeri M: Patients' and relatives' satisfaction with psychiatric services: the state of the art of its measurement. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:212- 227, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar