Personality and Clinical Predictors of Recurrence of Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To help clinicians more accurately predict outcomes of treatment for depression, variables associated with recurrence of depression in the year after treatment were examined in a group of patients who completed treatment for an index episode of depression. METHODS: Forty-two depressed patients who participated in a double-blind pharmacological treatment study were followed for one year after treatment was discontinued. Length of treatment for the index episode was determined by clinicians and ranged from eight to 76 consecutive weeks. Eighteen patients who had a recurrent episode (43 percent) and 24 patients who did not (57 percent) were compared on sociodemographic and clinical variables, including scores on the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ). RESULTS: A combination of three variables predicted recurrence of depression in 90 percent of cases. They were an elevated EPQ score on the neuroticism subscale, a short duration of treatment of the index episode, and a slow onset of response to treatment of the index episode. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that personality traits, treatment duration, and variations in response to treatment might have an impact on long-term treatment outcome. Clinicians should consider these factors when making treatment decisions for depressed patients.

Prediction of response to treatment for depression is an important aspect in the management of depressed patients, and several studies in the last decade have examined this issue. Although few reliable predictors have been found (1), efforts continue in this area. Finding biological, clinical, and psychosocial variables that predict which patients are at more risk of experiencing a recurrent episode of depression would benefit individual patients and improve pharmacological interventions.

Because depression is a recurrent disease in both its unipolar and its bipolar forms, prediction of subsequent episodes in the long-term outcome of depression is beginning to be explored (2). It has been postulated that for some patients, acute treatment that includes a sufficient medication dosage and duration of treatment may reduce the possibility of subsequent episodes in the short term. However, most studies are limited to predictors of acute response and give less attention to the evolution of depression once the index episode has remitted.

Some factors associated with a general positive response to treatment of depression are fewer previous episodes of depression (3), shorter episodes (4), younger age and relative absence of delusions (5), melancholic features (6), early onset of improvement (7,8), and better global and family functioning (9). However, these predictors are not entirely definitive.

Personality abnormalities may also play a role in treatment outcome. Controversy exists about whether measures of personality abnormalities taken during the acute phase of depression are only state markers of the severity of the disease. However, the presence of such abnormalities leads to a poor acute response to antidepressants (10) as well as to poor long-term prognosis (11). Thus personality traits have emerged as the strongest identified predictors of response to treatment of depression (12).

Chronic and nonchronic major depression have been differentiated in various studies by the presence of premorbid neuroticism (13,14). Scott and associates (15) have found that patients with persistent depression have higher neuroticism scores on the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ) (16). However, not all studies have supported the link between neuroticism and recurrent depression. For example, Joyce and colleagues (17) found that EPQ scores, including neuroticism scores, did not significantly predict the outcome of acute treatment.

The study reported here was intended to evaluate, on the basis of previous findings, whether a combination of certain clinical and therapeutic features and personality traits predicts recurrence of an acute depressive episode once patients have recovered from the index episode and treatment is withdrawn. Our main objective was to answer the following question: could better initial treatment conditions, including rapid onset of a highly positive response to antidepressant medication and an extended duration of treatment of the acute episode, along with the absence of personality abnormalities, produce longer periods of remission and reduce the possibility of new episodes? To answer this question, a prospective study in which patients were followed up after recovering from a depressive episode and after pharmacological treatment had ended was designed.

Methods

Patients were recruited from an outpatient study of major depression, conducted at our institution from October 1994 to March 1996, in which the clinical efficacy and tolerance of the antidepressants nefazodone and fluoxetine were compared. Subjects had to be between 18 and 65 years old, to be experiencing an episode of major depressive disorder with sufficient severity for diagnosis according to DSM-IV criteria (18), and to have scored at least 18 points on the first 17 items of the 21-item version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) (19). Patients were excluded if they had psychotic symptoms or a substantial suicide risk or if any other situation required hospitalization. A washout period of at least three weeks free of antidepressant medication was a requisite for all subjects. A period of at least one week was required to allow baseline evaluations, which included gathering clinical and sociodemographic data, carrying out basic laboratory tests, and administering the EPQ.

Patients who continued to meet entrance criteria and whose baseline physical examination and laboratory tests showed no significant abnormalities were started on an eight-week double-blind trial of active treatment. Evaluations were performed weekly and included use of the HAM-D as the main measurement of treatment efficacy, as well as other clinical scales to determine response and tolerance to treatment. Throughout the study each patient was evaluated by the same clinician who was blind to the EPQ score and to the treatment assigned.

A total of 54 patients completed the acute phase of the trial. Of these, 25 received nefazodone, at a mean dosage of 400 mg a day, and 27 received fluoxetine, at a mean dosage of 24 mg a day. No differences were found between treatment groups in either efficacy or tolerance. The results of the trial are reported in detail elsewhere (20).

The design of the trial included an extended long-term phase that permitted patients to continue receiving medication in a double-blind manner for as long as 76 consecutive weeks if necessary. The decision to continue treatment was based on the medical opinion of the clinician in charge of the patient, who determined, on the basis of the individual's personal antecedents and conditions, the length of treatment that would be of most benefit. In all cases discontinuation of treatment followed a slow tapering procedure. Patients with more severe symptoms or a greater number of previous episodes of depression tended to receive medication for longer periods. This approach allowed us to include in the study patients with different lengths of treatment, which ranged from eight to 76 consecutive weeks with practically the same dosage regimen.

Once treatment was discontinued and patients left the original study, they were followed monthly for the next 12 months to evaluate their clinical status. Each evaluation consisted of a general clinical interview, a physical examination, and use of a symptom checklist. A recurrent condition, according to the definitions used by Frank and colleagues (21), was determined to have occurred when any patient again fulfilled clinical criteria for major depression. If such an event occurred, treatment with antidepressant medication was reinstated.

Only 42 patients completed the one-year follow-up phase of the study and were included in the analyses reported here. The other 12 patients either refused to continue in treatment or were lost during the first month of the follow-up period, and they were considered treatment dropouts.

Patients were divided into two groups based on outcome—those who had no recurrence of depression during the year after treatment discontinuation and those who experienced a recurrent episode at any time during that year. The groups were compared on sociodemographic variables, including gender, age, occupation, and education level, and on clinical variables, including number of previous episodes of depression, length of the index episode, symptom severity at baseline, percentage of improvement after eight weeks of treatment, duration of treatment of the index episode, presence of melancholic features based on DSM-IV criteria, and comorbid axis I and II disorders.

A previous episode of depression was defined as a period during which the subject clinically qualified as having a major depressive episode that required pharmacological treatment for at least two consecutive months and that was followed by an asymptomatic period of at least six months before another episode occurred. The length of the index episode was calculated as the time elapsed between the date when the patient met full DSM-IV criteria for major depression and the date of a clinically defined onset of recovery. Duration of treatment of the index episode consisted of the number of weeks in which the patient received medication.

Scores on the EPQ, using the version translated and adapted for use in Mexico (22), were compared between groups. In all cases, patients were instructed to answer the items as descriptive of their normal selves. We expected that the number of previous episodes of depression, the severity of the index episode, and the time to recovery would predict recurrence of depression among these patients.

Categorical variables were analyzed using chi square tests or Fisher's exact test, and a one-way analysis of variance was used for the numerical data. To determine predictors of recurrence, multivariate analysis with a logistic regression model was used with a stepwise backward method in which variables that were significant in the univariate analysis were introduced into the model.

Results

Forty-two patients were followed for one year after medication was suspended. Of these, 24 (57 percent) had no recurrence of depression, and 18 (43 percent) had a recurrent depressive episode at some point during the follow-up period. No differences were found between the two groups in the type of medication received for the index episode. Thirteen of the patients with no recurrence of depression (54 percent) had received nefazodone, and 11 (46 percent) had received fluoxetine. Among the patients with recurrent depression, ten (56 percent) received nefazodone and eight (45 percent) received fluoxetine.

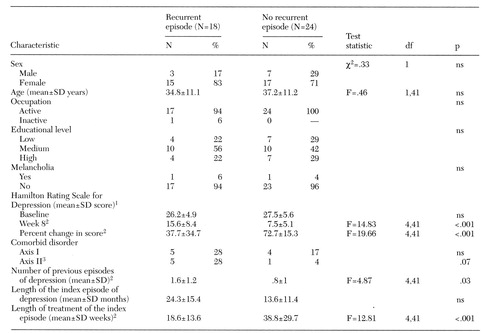

Table 1 presents clinical and sociodemographic information about both groups. Patients with no recurrence of depression differed from patients with recurrent episodes in the number of previous episodes, length of the index episode, duration of treatment of the index episode, and degree of response to antidepressant medication after eight weeks of treatment as measured by the percent change in the HAM-D score.

Compared with patients who had no recurrence of depression, those with recurrent episodes had significantly more previous episodes of depression, shorter duration of treatment of the index episode, and a less positive response after eight weeks of treatment as measured by the HAM-D score and by the percent change in the score. The index episode tended to last longer for these patients, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. Almost all patients in both groups were nonmelancholic. Of the six patients in the study with a comorbid axis II diagnosis, five experienced a recurrent episode of depression.

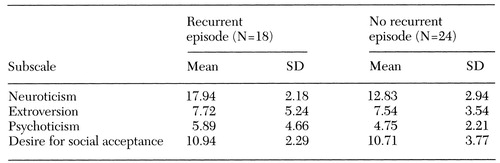

Mean EPQ scores for both groups are shown in Table 2. Significant differences were found only in scores on the neuroticism subscale. Patients who experienced a recurrent episode of depression had a higher neuroticism score.

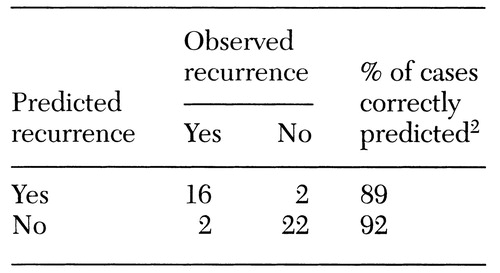

The multivariate logistic regression that included the statistically significant clinical and personality variables indicated that three variables increased the likelihood of patients' experiencing a recurrent episode in the year after treatment. They were the neuroticism score, duration of treatment of the index episode, and a slow onset of response to initial treatment. Together they predicted recurrence of depression in 90 percent of the patients (Table 3).

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study show that the personality trait of neuroticism in association with a slow onset of response to treatment of an index episode of major depression and a brief duration of treatment of the index episode predicted recurrence of major depression in a large proportion of patients. These findings are consistent with other reported results that depressed patients with personality deviations have a lower rate of recovery and an increased tendency to experience recurrent and chronic depression. One explanation is that patients with personality deviations have inadequate coping behaviors that exacerbate the effects of negative life events and thus contribute to the development of depression (23).

A slow onset of response to antidepressant treatment is also a useful predictor of recurrence. It has been demonstrated that the rate of improvement during the first weeks of treatment strongly predicts the outcome of depression (7). However, most of these studies focus only on the outcome of acute treatment, when the majority of symptoms are under control. The study reported here showed that the predictive value of response to acute treatment of eight weeks' duration can be extended to the long-term evolution of the disorder. Patients who had a better or a more complete response after two months of treatment had a more favorable outcome during the year after medication was withdrawn in that they were less likely to experience a recurrent episode of depression than patients with a poorer initial treatment response.

Our study also showed that duration of treatment of the index episode was a major predictor of long-term outcome, although this relationship was confounded by the strong correlation between duration of treatment and number of previous episodes. Clinicians gave more prolonged treatment during the index episode to patients who were experiencing recurrent depression, which is a consistent finding of other studies (24,25). Regardless of the number of past episodes of depression, abbreviated treatments tend to lead to relapse and recurrence. Taking medication for a sufficient period reduces the recurrence of depressive episodes. When symptoms of depression recur after a patient experiences a good response to acute treatment and four to six months of stabilization, biological recovery has not been completely consolidated, and the patient is at risk of a recurrence of major depression (26). For these patients, extending the treatment period could prevent the onset of a new episode.

Unfortunately, it has not been possible to definitively predict which patients would need such an extension of treatment. However, in the study reported here, a combination of three factors had a high overall predictive value of recurrence of depression, 90 percent. Thus these factors are important to consider in deciding how and how long to treat a depressed patient. An interesting finding was that although patients who had more previous episodes of depression were more likely to experience a recurrent episode in the follow-up year, logistic regression analysis did not find that the number of previous episodes was a strong predictive factor. The regression model also indicated that the length of the index episode was not a strong predictor of recurrence.

The results of this study show that neurotic personality traits may affect the evolution of depression once pharmacological treatment has controlled acute manifestations. One limitation of the study is that the small sample size does not allow us to draw firm conclusions. Further studies that address the difficulties inherent in long-term follow-up designs are required before definitive conclusions can be reached. The pharmacological treatment of depression must constantly be reevaluated to determine more precisely which patients do and do not need medication, how much medication is needed, and for how long it should be taken. Overtreatment and undertreatment must be avoided, and our results may help clinicians achieve this goal.

Many studies that address prevention of recurrence of affective disorders extend treatment with either medication or placebo beyond the usual treatment period. In other such studies, once remission is obtained with treatment, patients are switched to placebo or maintained on the antidepressant in a double-blind condition. Greenhouse and associates (27) concluded that the study design in which patients are randomly assigned to the test drug or to placebo after a period of stabilization have some methodological deficiencies. One deficiency is that some patients experience problems when the antidepressant being tested is abruptly discontinued.

The design of the study reported here closely resembles day-to-day clinical practice, which may make our findings of value to clinicians determining how to treat depressed patients. Clinicians tend to maintain longer treatment periods for patients who have had a greater number of previous episodes, those who have more severe symptoms, and those who have a comorbid condition. In our study the decision about how long to maintain patients in treatment once they responded to the medication was strictly a clinical decision.

The authors are affiliated with the clinical services division of the Mexican Institute of Psychiatry, Avenue México-Xochimilco 101 Colonia San Lorenzo Huipulco, Tlalpan, Mexico D.F. 14370 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 30-June 4, 1998, in Toronto.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 42 patients who did or did not experience a recurrent depressive episode in the year after completing treatment for an index episode

1Possible scores range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating a greater level of depression.

2Significant difference after one-way analysis of variance

3Significant difference as indicated by Fisher's exact text

|

Table 2. Scores on the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire of 42 patients who did or did not experience a recurrent depressive episode in the year after completing treatment for an index episode1

1Scores on the subscales range from 0 to 23, with higher scores indicating a greater level of the characteristic measured. One-way analysis of variance found a significant between-group difference on the neuroticism subscale only (F=38.35, df=1,41, p<.001).

|

Table 3. Number of patients predicted to have a recurrent depressive episode using a combination of three factors1

1The three factors predicting recurrence were an elevated score on the neuroticism subscale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, a slow response to treatment of the index episode, and a shorter treatment period for the index episode.

2Overall percent of cases correctly predicted=90%

1. Joyce P, Paykel ES: Predictors of drug response in depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:19-29, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, et al: Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:809- 816, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Akiskal HS: New insights into the nature and heterogeneity of mood disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 50:6-10, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kocsis JH: New issues in the prediction of antidepressant response. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 16:49-53, 1990Google Scholar

5. Brown RP, Sweeney J, Frances A, et al: Age as a predictor of treatment response in endogenous depression. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 3:176-178, 1983Medline, Google Scholar

6. Deykin EY, DiMascio A: Relationship of patients' background characteristics to efficacy of pharmacotherapy in depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 155:209-215, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nagoyami H, Nagano K, Ikesaki A, et al: Prediction of efficacy of antidepressants by 1-week test therapy in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 23:213-216, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Volz HP, Müller H, Sturm Y, et al: Effect of initial treatment with antidepressants as a predictor of outcome after 8 weeks. Psychiatry Research 58:107-115, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Miller EW, et al: Psychosocial factors and the long-term course of major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 44:57-67, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Nelson EC, Cloninger CR: The tridimensional personality questionnaire as a predictor of response to nefazodone treatment of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 30:35-46, 1995Google Scholar

11. Scott J, Eccleston D, Boys R: Can we predict the persistence of depression? British Journal of Psychiatry 161:633-637, 1992Google Scholar

12. Alnaes R, Torgersen S: Personality and personality disorders predict development and relapses of major depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 95:336-342, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Akiskal HS, King D, Rosenthal T: Chronic depression: part 1. clinical and familial characteristics in 137 probands. Journal of Affective Disorders 3:297-315, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Scott J: Chronic depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 153:287-297, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Scott J, Williams JMG, Brittlebank J, et al: The relationship between premorbid neuroticism, cognitive dysfunction, and persistence of depression: a 1-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders 33:167-173, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG: Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. London, Hodder Stoughton Educational, 1975Google Scholar

17. Joyce PR, Mulder R, Cloninger CR: Temperament predicts clomipramine and desipramine response in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 30:35-46, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

19. Hamilton MA: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 23:56-62, 1960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Berlanga C, Arechavaleta B, Heinze G, et al: A double-blind comparison of nefazodone and fluoxetine in the treatment of depressed outpatients. Salud Mental 20:1-8, 1997Google Scholar

21. Frank KE, Prien RF, Jarret DB, et al: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:851-855, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Eysenck SBG, Lara CMA: A transcultural study of personality in Mexican and English adults. Salud Mental 12:14-20, 1989Google Scholar

23. Vollrath M, Alnaes R, Torgersen S: Differential effects of coping in mental disorders: a prospective study in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology 52:126-135, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Weissman NIM, Kasl FV, Klerman GL: Follow-up of depressed women after maintenance treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 133:757-760, 1976Link, Google Scholar

25. Kiloh LG, Andrews G, Nelson M: The long-term outcome of depressive illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 153:752-757, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Maj M, Voltro F, Pirozzi R, et al: Patterns of recurrence of illness after recovery from an episode of major depression: a prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:795-800, 1992Link, Google Scholar

27. Greenhouse JB, Stangl D, Kupfer DJ, et al: Methodological issues in the maintenance therapy clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:313-318, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar