Subgroups of Frequent Users of an Inpatient Mental Health Program at a Community Hospital in Canada

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined demographic and clinical characteristics of frequent users of mental health services at a large community hospital in an urban-suburban area in Canada to identify subgroups within this patient population. METHODS: Patients who had had three or more inpatient admissions over any 12-month period between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 1995, were included in the study. Medical records were reviewed to collect summary data on 23 variables encompassing demographic characteristics and admission and discharge information. Quick cluster analysis was performed to identify subgroups within the frequent-user population. Chi square tests and analysis of variance were used to analyze group differences between clusters. RESULTS: Three patient subgroups accounted for 67 of the 83 patients (80.7 percent) identified as frequent users. Admission patterns were the strongest predictors of subgroup differences. CONCLUSIONS: Identifying subgroups within the frequent-user population may help in developing appropriate treatment and discharge plans with the aim of reducing the need for frequent utilization of inpatient mental health services.

The average hospital stay for inpatient mental health programs in North America has decreased from 120 days to less than 30 days over the past 40 years. It has been hypothesized that due to this decrease in length of hospital stay, numerous short rehospitalizations have been substituted for prolonged inpatient care (1).

The rehospitalization rate for frequent users of the mental health system ranges from 45 percent to 53 percent of the total number of admissions in a one-year period (1,2,3). Typically, 30 to 35 percent of inpatient consumers account for the use of 75 to 80 percent of allocated mental health inpatient dollars (2,3,4,5), and between 4 and 5 percent consume 20 to 25 percent of the inpatient dollars (2,6).

Noncompliance with medication, inadequate housing, and limited aftercare have often been postulated as the most frequent reasons for readmission to inpatient psychiatric services, but they have not been found to be significantly related to recidivism (7,8). Studies have identified several variables significantly related to recidivism, including a brief hospital stay, early age at onset of mental health problems, previous psychiatric admissions, and brief periods of time in the community between admissions (1,2,8). These findings suggest that recidivism is best predicted by retrospective measures such as previous psychiatric admissions.

However, several researchers are now suggesting that frequent users of mental health facilities constitute a distinct subgroup within the mental health inpatient population and that characteristics of this subgroup may assist in identifying patients at risk for frequent use of mental health facilities (2,8). Casper and Donaldson (9) have taken this hypothesis one step further and have postulated that not only are frequent users a distinct subgroup within the mental health patient population, but that subgroups within this frequent-user population can be identified by specific social-demographic and admission variables. In a study testing this hypothesis, Casper and Donaldson (9) grouped 60 of 87 patients (69 percent) into six clusters. The clusters were distinguished from each other by diagnoses of cognitive or mood disorders, gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, substance abuse, and violent behaviors (9,10).

The purpose of the study reported here was to identify specific subgroups within the mental health inpatient population at an urban-suburban community hospital near Toronto, Ontario, and to identify specific predictors of recidivism that would assist in program development and the allocation of shrinking health care resources.

Methods

This study was conducted retrospectively at Peel Memorial Hospital, a community hospital near Toronto. The hospital has 334 medical and 46 acute mental health beds. The inpatient mental health program provides treatment to adults and adolescents.

Readmission rates were calculated for the period between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 1995, the index period for this study. During this time the inpatient mental health program had 2,980 admissions, of which 1,533 involved patients who either had used the services in the past or were admitted more than once during the index period. The program therefore had a readmission rate of 51.4 percent during the index period.

A recidivism group was selected from the hospital readmission data. The inclusion criterion for the recidivism group was three or more inpatient admissions over 12 months during the index period. A total of 83 patients met this criterion and constituted the recidivism group.

Medical records were reviewed, and summary data were collected on 23 variables from each patient's first admission during the index period, unless otherwise noted. The data covered ten social and demographic variables, ten admission variables, and three discharge variables. The social and demographic variables were age, age at onset of mental health problems, living arrangements, marital status, number of children, employment status, level of education, presence of legal problems, history of substance abuse, and past physical or sexual abuse.

The admission variables were year of first admission to Peel Memorial Hospital, legal status at admission, length of hospital stay (in days) during first admission, average length of subsequent hospital stays (excluding the first admission), length of time in the community between the first and second admission (in days), average length of time in the community between readmissions (excluding the first admission), total number of admissions in a 12-month period falling within the index period, total number of admissions to the mental health program, reason for first admission, and the DSM-III-R axis I and II diagnoses (from the final admission during the index period). Discharge variables were destination to which the patient was discharged, use of community support systems, and type of professional who did follow-up.

Quick cluster analysis was performed on the 23 variables. Quick cluster analysis, a statistical method for finding subgroups of individuals who share similar values on a set of variables, builds group clusters by finding cluster centers based on values of variables and assigning cases to the clusters that produce the best-fit model. Chi square tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed on the resulting three clusters to analyze between-group differences on the 23 variables.

Results

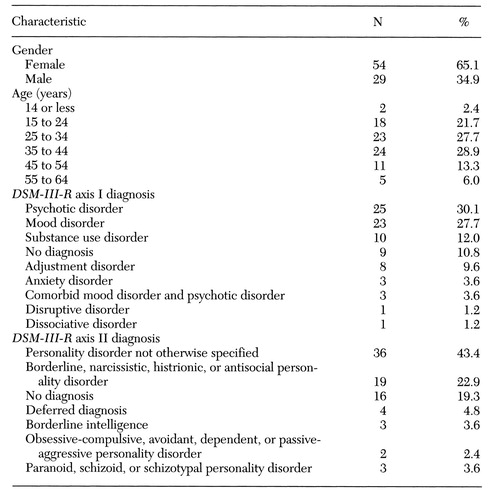

Eighty-three patients formed the recidivism group. Table 1 shows the group's demographic and diagnostic characteristics. Fifty-four patients were female, and 29 were male. Almost 57 percent were between 25 and 44 years of age. The two most frequent DSM-III-R axis I diagnostic groups were psychotic disorders and mood disorders. The most frequent axis II diagnosis was personality disorder not otherwise specified. Almost 23 percent of the patients had a personality disorder in the dramatic-emotional cluster, such as borderline, narcissistic, histrionic, or antisocial personality disorder.

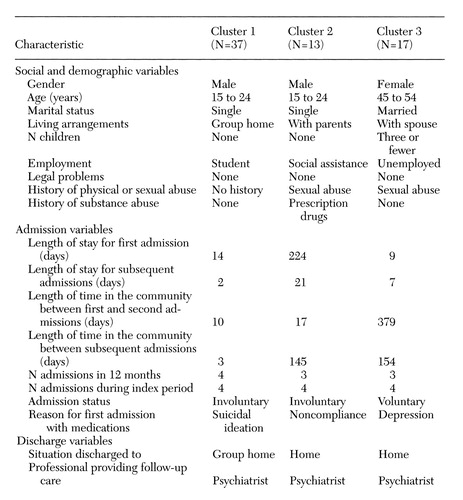

Quick cluster analysis produced three patient subgroups that together accounted for 67 of the 83 patients identified as recidivists, or 80.7 percent. As Table 2 shows, the three clusters were grouped on nine social-demographic variables, eight admission variables, and two discharge variables.

Cluster 1 comprised 37 patients. The prototypical member was a single male with no legal problems, no history of physical or sexual abuse, and no history of substance abuse. The average length of hospital stay for his first admission during the index period was 14 days, and the length of his subsequent hospital stays was two days. The length of time in the community between the first and second admission was ten days. All subsequent periods between admissions were three days. Over a 12-month period, his total number of admissions was four. Similarly, his total number of admissions during the entire index period was four.

Members of cluster 1 were admitted on a 72-hour involuntary admission for assessment and were typically admitted for suicidal ideation. The prototypical members of cluster 1 were discharged to a group home setting and received follow-up care from a psychiatrist. Because of universal health insurance in Canada, payment for psychiatric follow-up was not an issue.

Cluster 2 was made up of 13 patients, predominantly single males. The prototypical member of this cluster lived with his parents, received some form of social assistance, had a history of sexual abuse, and had a history of prescription drug abuse. The length of stay was 224 days for his first admission and 21 days for all subsequent admissions. Time in the community between his first and second hospital admissions was 17 days, and his length of time in the community between all subsequent admissions was 145 days. Over a 12-month period he had three admissions. His number of admissions during the entire index period was four.

Typically, the first admission for members of cluster 2 was an involuntary admission to address noncompliance with their medication. They were discharged home after their first admission and received follow-up care from a psychiatrist.

The prototypical member of cluster 3, which included 17 patients, was an unemployed woman, aged 45 to 54 years, who had three or fewer children, was married, and lived with her spouse. She had no history of legal problems or substance abuse but did have a history of sexual abuse. The length of hospital stay was nine days for her first admission and seven days for all subsequent admissions. Her length of time in the community between the first and second admissions was 379 days, and her length of time in the community between all subsequent admissions was 154 days. Her total number of admissions during a 12-month period was three.

Typically, members of cluster 3 had a total of four admissions during the index period. Generally, these admissions were voluntary and were due to depression. The members of cluster 3 were usually discharged home and received follow-up care from a psychiatrist.

To further analyze the data, chi square tests were done to determine whether the three clusters differed on qualitative cluster variables. No significant group differences were found between the three clusters on the qualitative social, demographic, or discharge variables.

However, results of a univariate ANOVA showed significant differences between groups on several admission variables. Significant mean differences were found between the three clusters on the length of time in the community between the first and second admissions (F=148.10, df= 2,64, p≤.001). Results of a Tukey-B HSD post hoc test indicated that members of cluster 3 spent more time in the community between the first and second admission—a mean of 241.94±67.09 days—than members of either cluster 1 or cluster 2, who were in the community a mean of 38.56±31.14 days and 35.15±24.89 days, respectively (p≤.05).

Significant mean differences between clusters were also found for the average length of time in the community between all subsequent admissions (F=35.14, df=2,64, p≤.001). The Tukey-B HSD post hoc test showed that members of cluster 2 spent more time in the community between subsequent admissions—a mean of 158.46±41.47 days—than members of cluster 1 and cluster 3, who spent a mean of 51.73±25.64 and 83.91±58.99 days in the community, respectively (p≤.05). In addition, members of cluster 3 spent more time in the community than did members of cluster 1 (p≤.05).

Significant differences were also found between clusters for the mean number of admissions within a 12-month period during the index period (F=5.10, df=2,64, p≤.01). The Tukey-B HSD post hoc test showed that cluster 1 had more admissions than cluster 2 during their sickest 12-month period—a mean of 4.81±1.9 admissions, compared with 3.38±.65 admissions (p≤.05). Cluster 3 had a mean of 3.64±1.32 admissions during their sickest 12-month period.

Discussion and conclusions

The readmission rate of 51.4 percent for the inpatient mental health program where the study was done does not differ significantly from the readmission rates of between 45 and 53 percent reported in the literature (1,2,3). Our results suggest that young adults constitute the greatest proportion of the recidivist population. Further, more than half of the recidivist group were suffering from a serious mental illness of either a psychotic or a mood disorder. These results are similar to those of other studies (1,2,81,2,8).

The formation of three distinct clusters of recidivist patients suggests that identifying patients with these group characteristics and developing treatment plans or programs that address these characteristics may reduce the patients' need for frequent rehospitalizations. All study patients had publicly funded access to a psychiatrist and thus may require more than follow-up visits to a psychiatrist to reduce their need for psychiatric readmission. Discharge planning should incorporate referrals to appropriate service agencies once the patient has been medically stabilized.

Admission patterns, including number and length of admissions and length of time in the community between admissions, were significantly different between the three clusters. These distinctive admission patterns may assist in identifying patients at risk for multiple future readmissions.

The hospital where the study was conducted is developing modified systems of acute and aftercare programs in its catchment area to address individual patients' needs. This approach merits further study to ascertain if service utilization patterns have been altered by the introduction of additional ambulatory services in the community.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Val Watt, David Duncan, Ph.D., Ruth Slater, Ph.D., and Susan Wilson, Ph.D.

Ms. Fisher is a researcher and Dr. Stevens is a psychologist in the mental health program at Peel Memorial Hospital in Brampton, Ontario, Canada. Address correspondence to Dr. Stevens at Peel Memorial Hospital, 120 Lynch Street, Brampton, Ontario, Canada L6W 2Z8 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of 83 patients identified as frequent users of inpatient mental health services at a community hospital1

1Frequent users of inpatient services had three or more admissions in any 12-month period between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 1995.

|

Table 2. Prototypical characteristics of three cluster subgroups of frequent users of inpatient mental health services identified by quick cluster analysis

1. Eaton WW, Mortensen PB, Herrman H, et al: Long-term course of hospitalization for schizophrenia:1. risk for rehospitalization. Schizophrenia Bulletin 18:217-227, 1992Google Scholar

2. Hadley T, McGurrin M, Pulice R, et al: Using fiscal data to identify heavy service users. Psychiatric Quarterly 61:41-48, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Holohean E, Pulice R, Donahue S: Utilization of acute inpatient psychiatric services: "heavy users" in New York State. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 18:173-181, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Appleby L, Desai PN, Luchins DJ, et al: Length of stay and recidivism in schizophrenia: a study of public psychiatric hospital patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:72-76, 1993Link, Google Scholar

5. Casper ES, Romo JM, Randal DF: Readmission patterns of frequent users of inpatient psychiatric services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1166-1167, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Hadley TR, Culhane DP, McGurrin MC: Identifying and tracking "heavy users" of acute psychiatric inpatient services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 19:279-289, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Boydell KM, Malcolmson SA, Siderbol K: Early hospitalization. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 36:743-745, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Haro JM, Eaton WW, Bilker WB, et al: Predictability of rehospitalization for schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 244:241-246, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Casper ES, Donaldson B: Subgroups in the population of frequent users of inpatient services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:189-191, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Casper ES: Identifying multiple recidivists in a state hospital population. Psychiatric Services 46:1074-1075, 1995Link, Google Scholar