Patterns of Health Care Costs Associated With Depression and Substance Abuse in a National Sample

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The associations between self-reported depressive and substance use disorders and estimated health care costs were examined in a representative national sample. METHODS: Data were from the 1994 National Health Interview Survey (N=77,183). Respondents who reported depressive symptoms or major depression (depressive syndromes) or a substance abuse disorder in the past year were compared with respondents who did not report these conditions. The mean number of inpatient days and outpatient visits in both the general medical and the specialty mental health settings were determined, and costs per individual were calculated based on mean costs of such care in each respondent's geographic region. Multivariate models were constructed to calculate mean costs, controlling for demographic variables, insurance coverage, and physical health status. RESULTS: Individuals with self-reported depressive syndromes or substance abuse had mean health care costs that were $1,766 higher than costs for individuals without these conditions. Depressive syndromes were associated with increases in both inpatient and outpatient costs. However, substance abuse was almost exclusively associated with increased inpatient expenditures rather than outpatient costs. The magnitude of increased costs associated with mental disorders was substantially larger for patients in fee-for-service plans than for those in health maintenance organizations. Only 14.3 percent of visits made by individuals reporting depressive syndromes or substance abuse were made to specialty health providers (psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers). CONCLUSIONS: Health care costs of people with self-reported mental illness varied significantly across diagnoses and systems of care. It is crucial that researchers estimating increased costs associated with mental illness account for both diagnostic and system factors that can influence the estimates.

A growing body of data highlights the impact of mental illness on morbidity and on health expenditures. Major depression is associated with substantial levels of disability (1), and total costs to society are estimated at $44 billion (2). Subsyndromal depression, due to its high prevalence, may be associated with as much morbidity as major depression at a population level (3,4). Substance abuse, including both alcohol and illicit drug use, has been estimated to cost the U.S. economy more than $144 billion per year (5). Studies based on the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey conducted in 1980 have emphasized the impact of depressive and subsyndromal disorders on days lost from work, disability (6), and use of specialty mental health services (4).

Mental health economists describe two categories of costs associated with mental illness—direct and indirect (5). Direct costs represent the costs incurred in treating the mental illness. Indirect costs include other costs to the individual, the health care system, and society, such as mortality and lost wages due to missed work and decreased productivity. In the general medical sector, indirect costs associated with mental illness may include expenditures related to increased medical morbidity, poor self-perception of health, or reduced adherence to outpatient treatment leading to inpatient hospitalization.

Several recent studies have examined the effect of depressive illness on health care expenditures in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), including two cost studies at Group Health Puget Sound. In one study, Simon and colleagues (7) found that primary care patients with depressive or anxiety disorders had baseline health costs of $993 per patient, or 1.7 times higher than per-patient costs for patients without anxiety or depressive disorders. In the other study the investigators found that patients already diagnosed by their treaters as having major depression had expenditures of $1,875 per patient, or 1.8 times higher than expenditures for patients without major depression (8). Other studies have extended these findings to older enrollees at the same HMO (9) and to high utilizers of care enrolled in an HMO in Madison, Wisconsin (10).

Alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence are among the most common psychiatric disorders found in community samples (11), and, like depression, these conditions may increase total health care utilization through both direct treatment costs and accompanying medical complications such as hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HIV-AIDS (12). However, in contrast to depression, the residential and social instability associated with addictive disorders may simultaneously lead to reduced access to outpatient medical services (13). The net effect of substance abuse on use of health services in the general medical sector thus remains uncertain.

The current literature leaves a number of gaps in understanding the relationship between mental illness and health care utilization. First, most of these studies have been conducted within single clinics or health plans, which limits their generalizability to other geographic regions and socioeconomic groups and makes it impossible to examine the effect of insurance status on use of services. Second, by focusing on only one mental illness, the studies have missed the opportunity to compare the patterns of health care utilization across different diagnoses. Finally, the majority of studies have focused only on undifferentiated, cumulative utilization or health charges. By examining inpatient and outpatient utilization separately, we may obtain a better understanding both of the mechanism of increased costs of mental illness and of the potential of specific interventions to offset those costs.

This study used data from the 1994 National Health Interview Survey, completed by a large sample of individuals from diverse geographic sites and socioeconomic backgrounds and with a variety of types of health coverage. We examined the estimated costs associated with self-reported mental disorders, focusing on individuals with depressive and substance use disorders.

Methods

Source of data

The sample was drawn from the 1994 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (14), in which members of 45,705 households in 198 separate U.S. regions were interviewed in their homes. The NHIS targets the civilian, noninstitutionalized population and has been conducted annually since 1957. It uses a complex, multistage probability design with oversampling of certain minority groups. Field operations for the survey are conducted by the U.S. Bureau of the Census under guidelines specified by the National Center for Health Statistics.

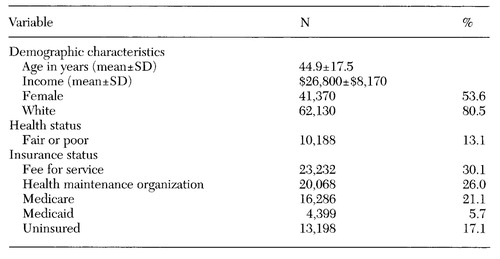

The total of 116,179 individuals surveyed in 1994 represented a 94.1 percent response rate to the survey. The 1994 survey included a disability supplement—the NHIS Disability Questionnaire—which included a number of questions about mental symptoms and mental illness. For this study, we included all respondents over the age of 18 (N=77,183). The demographic characteristics of the population, which are shown in Table 1, reflected the sampling design and were similar to the characteristics of adults living in the U.S.

Independent variables

Markers for mental illness. The NHIS Disability Questionnaire contains questions about depressive symptoms ("Are you frequently depressed or anxious?") and about major depression ("During the past 12 months, did you have major depression? Major depression is a depressed mood and loss of interest in almost all activities for at least two weeks.") It also has questions on alcohol abuse ("During the past 12 months, did you have an alcohol abuse disorder?") and drug abuse ("During the past 12 months, did you have a drug abuse disorder?"). For the study reported here, the latter questions were combined into a single substance abuse variable.

We created a set of five mutually exclusive diagnostic categories based on NHIS questions: major depression, depressive symptoms only, substance abuse only, comorbid depression and substance abuse, and no disorder. A dichotomous variable indicating individuals with any substance abuse or depressive syndrome (depressive symptoms or major depression) was also created for summary analyses.

A total of 5,253 individuals, or 6.8 percent of the sample, reported evidence of any depressive syndrome or substance abuse disorder in the past year. Within that group, 3,372 people (68 percent) reported depressive symptoms in the absence of major depression, 1,081 (22 percent) reported major depression, 281 (6 percent) reported substance abuse without accompanying depression, and 210 (4 percent) reported both a depressive syndrome and a substance abuse disorder.

Demographic variables. Demographic variables described in the literature as influencing use of health services include age (15), race (16, 17), sex (18), and income (19). Data on these variables were available in the NHIS database, and they were included in all multivariate models.

Studies have also documented variability in hospital charges based on geographic region (19,20). NHIS region codes, which correspond to divisions used by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, were included in all multivariate analyses and used to control for geographic variation in costs.

Health insurance status. The health insurance supplement to the 1994 NHIS asks respondents detailed questions about their health coverage. Dichotomous mutually exclusive variables were constructed to adjust for insurance status. They were fee-for-service, HMO, Medicare, Medicaid, and uninsured.

Physical health status. Physical health status was controlled for using self-reported health status (a 5-point scale ranging from 1, excellent, to 5, poor). The use of self-reported health status is an established method of risk adjustment for severity of medical illness (21,22).

Dependent variables

The NHIS asked respondents to report the number of days they spent in a hospital during the past 12 months and the number of physician visits in the past two weeks. The latter variable was annualized to produce 12-month estimates. The two measures were used as dependent variables when examining the effect of psychiatric syndromes on service use and as the basis for calculating cost estimates. Reports from similar surveys (23), and the NHIS in particular (24), have suggested the general accuracy of self-reported data in measuring health care service use.

Cost estimates

Inpatient costs. The American Hospital Association (AHA) conducts an annual survey of hospitals that includes data on hospital utilization, personnel, and finances. Adjusted costs per inpatient day are calculated as expenses incurred by the hospital. Data from the 1994 AHA survey included information on 5,577 short-term, nonfederal facilities; they reflected an 89.5 percent response rate, with similar response rates across different locations and hospital sizes (25). For the study reported here, inpatient costs were estimated as the mean inpatient daily cost for a given respondent's census division multiplied by the number of inpatient days in the year before the survey.

Outpatient costs. The American Medical Association publishes an annual report of physician fees by specialty and geographic region. The 1994 survey included data on 2,478 physicians, with an overall response rate of 63.1 percent (26). Response rates were comparable across specialties and geographic sites. For the study reported here, total outpatient costs were calculated by multiplying mean fees per outpatient visit for the respondent's census division by the number of outpatient visits reported in the past year.

Data analysis

Costs associated with depressive disorders (depressive symptoms and major depression) and substance abuse were calculated as the excess costs for respondents, with costs for patients with each disorder compared with costs for patients without any of the disorders. Separate multivariate equations modeled each cost variable as a function of the five categories of mental disorder, controlling for age, race, sex, income, geographic region, health insurance status, and self-reported physical health. Least-square means were calculated for costs associated with each mental category controlling for these covariates. The increased costs associated with depressive disorders and substance abuse were calculated by subtracting the adjusted mean cost for patients without depressive syndromes or substance abuse disorders from the cost for patients with each disorder of interest.

Because of the skewed distribution of utilization and cost data, all statistical comparisons are based on log-transformed values. The SUDAAN statistical package (27), with appropriate weighting and nesting variables, was used for all statistical comparisons, because of the complex stratified survey design.

Results

Mental disorders and estimated costs

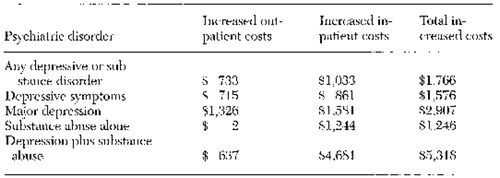

Table 2 presents the costs attributable to depressive disorders and substance abuse. After the analyses adjusted for demographic variables, insurance status, and health status, people with any depressive or substance abuse disorder had average costs that were $1,766 higher than people without these conditions. These incremental costs varied substantially among disorders, ranging from a low of $1,246 for individuals with substance abuse to a high of $5,318 for comorbid substance abuse and depressive syndromes.

Patterns of service use differed substantially across diagnoses. People with depressive symptoms with or without major depression had significantly increased costs for both inpatient and outpatient care. In contrast to depressive syndromes, substance abuse disorders primarily appeared to be associated with increased inpatient costs. People who reported substance abuse alone had increases in inpatient costs but not in outpatient expenditures, compared with those without depression or substance abuse. Individuals with comorbid depressive syndromes and substance abuse had patterns more similar to those with substance abuse disorders than those with depressive syndromes, with very large increases in inpatient expenditures and much smaller, although significant, increases in outpatient costs.

Distribution of costs between sectors

To assess whether increased health costs were primarily a function of visits for mental health care or medical care, we compared the distributions of outpatient mental health and general medical visits in this group. (Parallel information for inpatient costs was not available from the NHIS). Only 14.3 percent of visits made by individuals reporting depressive symptoms or substance abuse were made to specialty health providers—psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers.

Variation across insurance types

Having depressive syndromes or substance abuse was associated with significantly increased use of services regardless of insurance type. However, the magnitude of the incremental costs varied significantly under different forms of coverage. The largest cost increase associated with these conditions was seen for individuals covered by Medicare and Medicaid, where mean incremental costs associated with the conditions were $2,124. The lowest additional expenditures were seen for the uninsured; for them the conditions were associated with increased expenditures of only $920.

For individuals with private insurance, expenditures varied significantly based on type of coverage. Under fee-for-service care, individuals with depressive symptoms or substance abuse had a mean cost for services that was $2,057 higher those without these conditions. This value was significantly larger than the increased mean cost of $1,479 associated with these conditions in HMOs.

Discussion

With the growth of managed care and the accompanying emphasis on cost containment and population-based delivery of health services, purchasers, providers, and consumers share a common interest in identifying potentially modifiable causes of increased health services utilization. We found comparably high incremental costs, but differing patterns of utilization, between individuals with substance abuse and those with depressive syndromes. We also found differences in expenditures associated with depressive syndromes and substance abuse under different types of insurance, with substantially larger expenditures in fee-for-service plans than in HMOs.

The increased outpatient costs associated with the depressive syndromes and substance abuse were primarily driven by general medical visits rather than by visits to specialty mental health care providers. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that more than 90 percent of costs attributable to depressive illness in general medical settings are incurred in the general medical sector, rather than in specialty mental health settings (8).

The study found that for individuals with depressive symptoms alone, costs were substantially lower than for individuals with reported major depression, indicating a graded relationship between severity of depressive symptoms and health care utilization. However, because the prevalence of depressive symptoms alone is approximately three times that of major depression, the results suggest that the total costs and the morbidity associated with such symptoms are as high as or higher than the costs associated with major depression. The findings are consistent with previous studies describing the high morbidity and costs associated with subsyndromal depression (28,29).

Whereas the higher costs associated with depression were equally distributed between outpatient and inpatient health services, the higher costs associated with substance abuse resulted almost entirely from higher inpatient utilization. A number of factors, including comorbid medical illnesses, may increase the need for health services for patients who abuse substances and may lead to higher inpatient costs (12). At the same time, other factors, such as reduced access to health insurance and social instability, may serve to reduce utilization of outpatient services in this population (13). The pattern of moderate outpatient costs and very high inpatient costs seen among patients with dual diagnoses may reflect still higher levels of medical and mental health need coupled with poor access to, or poor compliance with, outpatient care.

Finally, we found that while depressive syndromes and substance abuse were associated with increased costs across all types of insurance, the increase in costs varied depending on coverage. Costs attributable to depressive syndromes and substance abuse were substantially lower for patients in HMOs than in fee-for-service plans. One possible explanation for this finding is that individuals who select HMOs are healthier than those who enroll in fee-for-service plans (30). Indeed, compared with NHIS respondents who were enrolled in HMOs, respondents covered under fee-for-service arrangements were 1.4 times more likely to report fair or poor health (9.1 percent versus 6.7 percent).

However, significant cost differences persisted even after the analyses controlled for case mix, suggesting that the differences in expenditures may also reflect different patterns of treatment between HMOs and fee-for-service care. Such findings would be consistent with previous reports that HMOs provide lower-intensity treatment than fee-for-service systems (31).

The major limitation of using NHIS data to estimate costs of services is that the marker for mental illness, as well as estimates of utilization, was based on self-report. The prevalence of self-reported psychiatric illnesses in this sample was substantially lower than prevalence rates in studies using diagnostic interview schedules (32,33). Underreporting of psychiatric disorders is most commonly seen among individuals who have less severe illnesses or who have not received treatment (34). Thus use of self-reported diagnoses would be expected to lead to some overestimation of the costs per individual and some underestimation of the prevalence of mental disorders and of the total costs, as opposed to the mean costs, for an entire population.

Ultimately, any analysis of data not explicitly gathered for the purposes of measuring costs of mental disorders will have methodological shortcomings when the data are used for that purpose. However, an inevitable trade-off exists between comprehensiveness and generalizability; smaller, more detailed studies may be difficult to extrapolate to different health systems, geographic regions, and diagnoses. Twenty years ago, David Mechanic (35) spoke of the need for health services researchers to draw from both types of studies to effectively address public-policy questions. Now, in a rapidly evolving health care system, it is more important than ever to be able integrate all of these sources of data to more fully assess the costs of mental illness in the United States.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by grants from the Donaghue Medical Research Foundation (DF96003) and from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression.

The authors are affiliated with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 950 Campbell Avenue (116A), West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). They are also affiliated with the departments of psychiatry and public health at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 77,183 respondents to the 1994 National Health Interview Survey

|

Table 2. Increased health care costs per individual attributable to psychiatric disorders among 77,183 respondents to the 1994 National Health Interview Survey1

1Costs were calculated as the difference between the mean costs for individuals with the disorder and those without depressive symptoms, major depression, or a substance abuse disorder, controlling for age, sex, race, income, geographic region, insurance status, and self-reported health status. All cost increases were significant (p<.001) except for the increase in outpatient costs associated with substance abuse alone.

1. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262:914-919, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, et al: The economic burden of depression in 1990. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:405-408, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

3. Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, et al: Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1411-1417, 1996Link, Google Scholar

4. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 267:1478-1483, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rice DP, Miller LS, Dunmeyer S: The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness. DHHS publication (ADM) 90-1694. Rockville, Md, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1990Google Scholar

6. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, et al: Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 264:2524-2528, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:352-357, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Simon G, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:850-856, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al: Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. JAMA 277:1618-1623, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Henk HJ, Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, et al: Medical costs attributed to depression among patients with a history of high medical expenses in a health maintenance organization. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:899-904, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Myers JK, Weissman MM, Tischler GL, et al: Six-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in three communities:1980 to 1982. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:959-967, 1984Google Scholar

12. French MT, Mauskopf JA, Teague JL, et al: Estimating the dollar value of health outcomes from drug abuse. Medical Care 34:890-910, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Use of medical services by veterans with mental disorders. Psychosomatics 38:451-458, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. National Center for Health Statistics:1994 National Health Interview Survey [database on CD-ROM]. CD-ROM Series 10, no 9. SETS Version 1.21a. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1994Google Scholar

15. Leventhal EA, Leventhal H, Schaefer P, et al: Conservation of energy, uncertainty reduction, and swift utilization of medical care among the elderly. Journal of Gerontology 48:78-86, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Navarro V: Race or class versus race and class: mortality differentials in the United States. Lancet 336:1238-1240, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Gornick ME, Eggers PW, Reilly TW, et al: Effects of race and income on mortality and use of services among Medicare beneficiaries. New England Journal of Medicine 335:791-799, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Stoverinck MJ, Lagro-Janssen AL, Weel CV: Sex differences in health problems, diagnostic testing, and referral in primary care. Journal of Family Practice 43:567-576, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wennberg J, Gittleshohn A: Small area variations in health care delivery. Science 182:1102-1108, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Rosenheck R, Astrachan B: Regional variation in patterns of inpatient psychiatric care. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:1180-1183, 1990Link, Google Scholar

21. Milunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, et al: Self-rated health status as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 50:517-528, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hornbrook MC, Goodman MJ: Chronic disease, functional health status, and demographics: a multidimensional approach to risk adjustment. Health Services Research 31:283-307, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

23. Brown JB, Adams ME: Patients as reliable reporters of medical care process. Medical Care 30:400-411, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. National Center for Health Statistics: Reporting of hospitalization in the Health Interview Survey. Vital and Health Statistics 2(6):1-71, 1965Google Scholar

25. Hospital Statistics:1996-1997 Edition. Chicago, American Hospital Association, 1996Google Scholar

26. Gonzalez ML: Physician Marketplace Statistics:1994. Chicago, American Medical Association, 1994Google Scholar

27. SUDAAN Release 7.0. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1997Google Scholar

28. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 267:1478-1483, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, et al: Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1411-1417, 1997Google Scholar

30. Druss BG, Allen HM, Bruce ML: Physical health, depressive symptoms, and managed care enrollment. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:878-882, 1998Link, Google Scholar

31. Norquist GS, Wells KB: How do HMOs reduce outpatient mental health care costs? American Journal of Psychiatry 148:96-101, 1991Google Scholar

32. Robins LN, Regier DA: Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

33. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:313-321, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Simon GE, VonKorff M: Recall of psychiatric history in cross-sectional surveys: implications for epidemiologic research. Epidemiologic Reviews 17:221-227, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Mechanic D: Correlates of physician utilization: why do major multivariate studies of physician utilization find trivial psychosocial and organizational effects? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 20:387-396, 1979Google Scholar