Consumer Perceptions of Involuntary Outpatient Commitment

Abstract

This study examined beliefs about the provisions of outpatient commitment and their effects among 306 people with severe and persistent mental illness who were awaiting a period of outpatient commitment. More than 80 percent of the respondents perceived that the court order for outpatient commitment required them to keep their appointments at the mental health center and to take medication as prescribed. More than three-quarters believed that the outpatient commitment order made it more likely that people would keep their mental health appointments, take their medication, and stay out of the hospital.

Involuntary outpatient commitment was originally conceived as a means to increase community tenure for people with severe mental illness, to reduce the risk of decompensation, and to provide necessary treatment by means that were less restrictive than hospitalization (1,2). However, concerns have been raised that outpatient commitment extends coercive interventions into community treatment (3,4).

Empirical investigations of the perceived coerciveness of outpatient commitment have produced mixed results (5,6,7; Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al., unpublished data, 1998). However, understanding a person's perceptions of coercion requires an understanding of the knowledge and beliefs on which those perceptions are based. No prior studies have systematically examined respondents' knowledge of outpatient commitment provisions and their perception of its effects.

In North Carolina the statutory criteria for outpatient commitment require the presence of a severe mental illness, the capacity to survive safely in the community with available supports, a clinical history indicating a need for treatment to prevent deterioration that would predictably result in dangerousness, and a mental status that limits or negates the individual's ability to make informed decisions to seek voluntarily or to comply with recommended treatment. The court order for outpatient commitment directs the respondent to comply with prescribed treatment but explicitly prohibits the use of physically forced medication or forcible detention for treatment unless the respondent poses an immediate danger to himself or others, in which case inpatient commitment should be initiated. If the respondent does not comply with the prescribed treatment, the treating clinician should make reasonable efforts to solicit compliance, but if these efforts fail, the clinician may then request that a law enforcement officer bring the respondent to a mental health center to be examined and, it is hoped, persuaded to comply with treatment.

In this study, we interviewed persons ordered to outpatient commitment to determine their perceptions of the requirements of the court order and its effectiveness in improving medication adherence and community tenure.

Methods

Data presented here come from a larger study of the effectiveness of outpatient commitment for improving outcomes among people with severe mental illness (8,9). The data were gathered between November 1992 and March 1997. Involuntarily admitted patients who were awaiting a period of outpatient commitment were recruited from the admissions unit of a regional state psychiatric hospital and three other inpatient facilities in North Carolina.

All subjects were required to reside within one of nine counties chosen for the study, to be at least 18 years old, to have had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or major mood disorder for at least a year, to have serious impairment in social functioning, and to have a recent history of intensive treatment. After patients were determined to be eligible for the study, they were approached for consent to participate in a face-to-face interview. Of the identified eligible patients, about 12 percent refused to participate. Refusal rates did not differ significantly by sex, race, or diagnosis.

The study sample was composed of 331 persons. Fifty-four percent were men, and 46 percent were women. Their mean±SD age was 40±11 years. More than half of the respondents, or 57 percent, completed high school, and most, or 81 percent, were not married or cohabiting.

Sixty-seven percent of the respondents were African American, and a substantial proportion of respondents—38 percent—resided in rural areas. A total of 68.5 percent had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or other psychotic disorder. An additional 27 percent had admitting diagnoses of bipolar disorder, and only a small minority—4.5 percent—had a primary diagnosis of depression. Cases were eliminated if data on the items involving the respondent's perception of outpatient commitment were missing, resulting in a final sample size of 306 respondents.

Results

Respondents' beliefs about the requirements of the outpatient commitment order were fairly consistent. Overall, 88.6 percent of respondents believed that outpatient commitment requires an individual to keep appointments at the mental health center (5.6 percent did not know). Also, 82.7 percent believed that this order also requires an individual to take medications as prescribed (6.2 percent did not know). We found no significant differences between respondents who had previous experience with outpatient commitment and those who did not with regard to beliefs about keeping appointments (96 percent versus 85 percent) or taking medication (89 percent versus 80 percent).

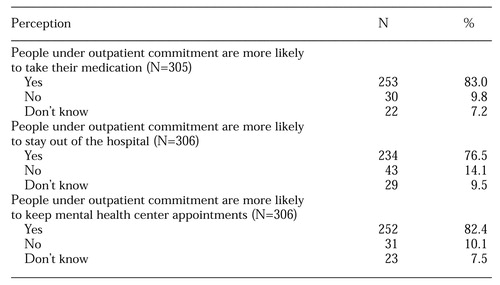

Table 1 summarizes respondents' beliefs about the effects of outpatient commitment. About 82 percent believed that when people are under outpatient commitment, they are more likely to keep their appointments at the mental health center. Seventy-seven percent thought that people under outpatient commitment are more likely to stay out of the hospital. Eighty-three percent of respondents thought people on outpatient commitment are more likely to take their medication. No significant differences in perceptions of effectiveness of outpatient commitment were found between those who had previous experience with outpatient commitment and those who did not.

However, in the entire sample, 91 percent of those who believed that outpatient commitment legally requires people to take medication but only 76 percent of those who did not believe in this requirement also believed that people under outpatient commitment are more likely to take their medication, a significant difference (Fisher's exact test, p=.01). The two groups were similar in their beliefs about the effectiveness of outpatient commitment in keeping people out of the hospital—86 percent and 79 percent.

Discussion and conclusions

In this sample of people with severe mental illness awaiting a period of outpatient commitment, a substantial majority perceived that the outpatient commitment court order required them to keep their appointments at the mental health center and to take medication as prescribed. These perceptions did not vary significantly according to whether or not the respondent had previously been under an outpatient commitment order. In addition, more than three-quarters of respondents believed that the outpatient commitment order made it more likely that people would keep their mental health appointments, take their medication, and stay out of the hospital. Thus people subjected to outpatient commitment seem to believe that it requires them to comply with two major treatment components, and they believe that it is effective in accomplishing its objectives.

A question arises, however, about how respondents may perceive the requirements of the court order. We asked whether the outpatient commitment order "required" respondents to attend appointments or to take medication. Although the order does direct the respondent to comply with prescribed treatment, it does not permit that requirement to be forcibly enforced.

However, respondents may have believed that they can be forced to comply. Respondents who had been subjected to inpatient commitment may have recalled that they were forcibly detained for treatment, that is, they were required to stay in the hospital involuntarily. Similarly, they may have observed or been subjected to forcible medication in an institutional setting. It may have seemed counterintuitive that a person could be required to do something without any provision to force adherence if the person failed to comply.

This potential misperception could raise important questions for practice and policy. As a practical matter, treating clinicians generally want their patients to take their medication as prescribed—and those patients apparently believe that outpatient commitment increases the likelihood that they will take medication. But what obligations, if any, do clinicians have to educate respondents about the actual provisions and limitations of their outpatient commitment? Should the judge who issues the order or the attorney representing the respondent make reasonable efforts to ensure that the respondent understands the provisions and limitations of the outpatient commitment mandates?

Although the use of coercive interventions generally is controversial, these data suggest that most people awaiting outpatient commitment do believe that this intervention can help keep people out of the hospital, which presumably is a desirable outcome for all parties. Further research should provide additional information about outpatient-commitment-related outcomes to inform policy decisions affecting the balance between patients' autonomy and the provision of necessary treatment.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant MH-48103 to Dr. Swartz from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Borum is associate professor in the department of mental health law and policy at the Florida Mental Health Institute of the University of Florida, 13301 Bruce B. Downs Boulevard, Tampa, Florida 33612 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Swartz is associate professor, Dr. Swanson is assistant professor, and Dr. Wagner is assistant research professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Riley is a postdoctoral fellow in the University of North Carolina-Duke Mental Health Services and Systems Research Training Program in Durham. Dr. Hiday is professor in the department of sociology and anthropology at North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

|

Table 1. Perceived effects of outpatient commitment among persons with severe and persistent mental illness awaiting a period of outpatient commitment

1. Hiday V: Outpatient commitment: official coercion in the community, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

2. Maloy K: Critiquing the empirical evidence: Does Involuntary Outpatient Commitment Work? Washington, DC, Policy Resource Center, 1992Google Scholar

3. Schwartz SJ, Costanzo CE: Compelling treatment in the community: distorted doctrines and violated values. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review 20:1329-1429, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stefan S: Preventive commitment: the concept and its pitfalls. Mental and Physical Disability Law Reporter 11:288-302, 1987Google Scholar

5. Swartz MS, Burns BJ, George LK, et al: The ethical challenges of a randomized controlled trial of involuntary outpatient commitment. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:35-43, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hiday VA: Coercion in civil commitment: process, preferences, and outcome. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 15:359-377, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Scheid-Cook TL: Contollers and controlled: an analysis of participant constructions of outpatient commitment. Sociology of Health and Illness 15:179-198, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, George LK, et al: Interpreting the effectiveness of involuntary outpatient commitment: a conceptual model. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:5-16, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

9. Swartz MS, Burns BJ, Hiday VA, et al: New directions in research on involuntary outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 46:381-385, 1995Link, Google Scholar