Course of Antidepressant Treatment, Drug Type, and Prescriber's Specialty

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined whether the relationship between the course of antidepressant treatment and the type of prescriber—psychiatrist or nonpsychiatrist—varied by whether a tricyclic antidepressant or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) was prescribed. METHODS: Pharmacy claims from a nationwide database were analyzed retrospectively. A total of 3,101 adults who did not have a prescription for antidepressants for nine months and who were then given a prescription for a tricyclic or an SSRI antidepressant were followed for 13 to 16 months after the initial prescription. Outcome measures were rates of treatment termination before one month and subtherapeutic dosing, defined as having received no prescribed daily dosages at or above commonly cited thresholds. RESULTS: Among tricyclic-treated patients, psychiatrists' patients were significantly more likely than nonpsychiatrists' patients to continue in treatment for more than one month (72 percent versus 62 percent). Among patients taking tricyclics for at least three months, those with at least one prescription from a psychiatrist had a significantly higher rate of therapeutic dosing than those with all prescriptions from a nonpsychiatrist (70 percent versus 25 percent). For SSRI-treated patients, rates of termination and therapeutic dosing did not differ significantly by prescriber type. In multivariate equations that controlled for selected differences, effects of drug type and prescriber type were independent when persistence in treatment was analyzed, and interactive when subtherapeutic dosing was analyzed. CONCLUSIONS: Policy making about antidepressant pharmacotherapy should include assessments of the relationships between drug selection and patient outcome across a variety of clinical settings.

Adequacy of antidepressant pharmacotherapy has emerged as an important health policy issue in recent years (1). Studies conducted in a variety of settings beginning in the 1980s have consistently documented high rates of premature termination and subtherapeutic dosing of antidepressant drugs (2,3,4,5).

In an effort to identify strategies to improve patient outcomes, investigators have examined factors associated with treatment adequacy. Studies including two randomized trials have found that patients treated by psychiatrists, either directly or in consultation-collaboration, are more likely to receive antidepressant treatment of adequate dosage or duration than patients treated in routine primary care alone (6,7,8,9).

The type of drug has also been associated with treatment adequacy in research comparing tricyclic antidepressant drugs with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Observational studies in a variety of settings have found that patients treated with SSRIs are more likely than those treated with tricyclics to persist in treatment and to receive therapeutic dosages (8,9,10). Moreover, a randomized trial in one health maintenance organization (HMO) found that patients initially treated with fluoxetine were more likely than imipramine- or desipramine-treated patients to continue the originally dispensed medication and to receive dosages in therapeutic ranges (11).

The association of both provider type and antidepressant type with treatment adequacy raises policy questions about the joint effects of these factors. Contending that using tricyclics in general practice is problematic because of adverse effects and dosing complexity, Thompson (12) hypothesized that routine use of SSRIs as first-line treatment would bridge the gap between psychiatric practice and primary care in treating depression. If confirmed by empirical research, this assertion—that outcomes of treatment for depression provided in primary care settings would more closely approximate those in psychiatric settings if SSRIs were used more often—might have policy implications for designing systems of referral from primary care to psychiatry.

In addition, in designing formulary policies, it would be helpful to know whether the consequences of procedural requirements for antidepressant selection vary depending on the availability of psychiatric specialty care. For example, under an administrative requirement that a patient fail treatment with a tricyclic before an SSRI can be used, do outcomes differ in systems with readily available consultation-liaison psychiatrists compared with systems in which access to psychiatric services is restricted? Despite the importance of such questions, only one observational study, set in a single HMO, has examined the joint effects of prescriber type and antidepressant type (9). That study found both factors to be independently associated with adequacy of duration and dosage.

The study reported here examined the relationships between prescriber type, antidepressant type, and treatment course, in a larger and more diverse sample than has been studied previously. The study is a retrospective analysis of drug claims from Express Scripts/ValueRx, Inc. (ESI/VRx), a pharmacy benefits management company. The company has a large, nationwide, and demographically diverse population including both HMO and indemnity-plan (fee-for-service) enrollees.

Methods

Study population

The study was part of a larger-scale antidepressant research project, details of which have been reported elsewhere (10). The study population consisted of adults age 18 and older who filled no antidepressant prescriptions during the last nine months of 1993 and subsequently filled at least one prescription for either a tricyclic or an SSRI during the first three months of 1994. The purpose of excluding patients who had used antidepressants in the previous nine months was to yield a population of first-time or episodic users, rather than chronic users. The first of the antidepressant prescriptions served as an index date, denoting the start of treatment. Patients were followed from the index date through April 30, 1995. The observation period before the index date was nine to 12 months, and after the index date it was 13 to 16 months.

Patients who were not continuously eligible to receive prescription benefits through ESI/VRx for the entire observation period (April 1, 1993, through April 30, 1995) were excluded. Also excluded were patients enrolled in either HMO or indemnity plans that restricted use of particular antidepressant products, and patients who used antidepressants in other drug classes, such as trazodone, buproprion, and venlafaxine. Patients taking more than one antidepressant drug because they were being switched to another drug or because their treatment was being augmented were included, both to maximize the study's external validity and because sensitivity analyses produced the same findings when data for these patients were excluded. However, patients who filled prescriptions for two different antidepressants on the index date were excluded.

The previously reported size of the resulting sample was 4,252 (10). However, the analyses reported in this paper include only a subset of 3,101 patients for whom prescriber information was available for all antidepressant claims.

Analytic procedures

Assessment of the course of antidepressant treatment included measures of length of treatment and daily dosages. They were calculated using data fields that are standardized on prescription claims nationwide. For each claim, the pharmacist designates a days'-supply figure that indicates how long the medication will last if taken as prescribed. The sum of the fill date plus the days'-supply figure equals the expected depletion date. Length of treatment was defined as the difference (number of months) between the index date and the last depletion date observed before the end of the study period on April 30, 1995. The prescribed daily dosage was calculated as the number of milligrams dispensed (number of pills times strength per pill) divided by the days' supply.

The first dependent variable was termination of treatment on or before one month, defined as a length of treatment less than or equal to 30 days. The second dependent variable, subtherapeutic dosing, was defined as a failure to receive at least one prescribed dosage meeting or exceeding therapeutic dosing standards. To distinguish therapeutic from subtherapeutic dosages of tricyclics, standards originally developed for the Medical Outcomes Study were used (5). For SSRIs, standards were drawn from the usual dosages listed in the Physicians' Desk Reference (13).

The resulting thresholds for patients age 60 or younger were 100 mg daily for amitriptyline, desipramine, doxepin, and imipramine; 75 mg daily for nortriptyline; 50 mg daily for sertraline; and 20 mg daily for paroxetine and fluoxetine. Standards for patients age 61 or older were lower: 75 mg daily for amitriptyline, desipramine, doxepin, and imipramine; 50 mg daily for nortriptyline; 25 mg daily for sertraline; and 10 mg daily for paroxetine and fluoxetine. To allow time for titration, the second dependent variable—subtherapeutic dosing—was measured only for patients who were treated for at least three months with one drug. For example, a patient treated six weeks with one drug and six weeks with another would be excluded from this analysis.

Independent variables included the patient's age on January 1, 1994; gender; type of insurance coverage (HMO or indemnity plan); and two measures of use of nonantidepressant medications during the nine to 12 months before antidepressant therapy. These measures were whether the patient used psychotropic drugs other than antidepressants and the monthly cost (average wholesale price) for all drugs (not just psychotropics).

A chronic disease score was calculated for the time period from six months before to six months after the index date, using an algorithm based solely on pharmacy claims data (14). Because pharmacy claims contain no diagnostic information, the algorithm imputes diagnoses from drug utilization incorporating measures of cardiac disease, respiratory illness, rheumatic disease, cancer, and other conditions. The summary chronic disease score reflects both the number and severity of chronic conditions, is predictive of subsequent hospitalization and mortality, and correlates with physicians' ratings of patients' disease severity (14).

Data about the prescriber's specialty were obtained by matching information in the American Medical Association national database to prescribers' Drug Enforcement Agency numbers, names, and addresses. For analyses of termination at one month, the physician who wrote the index antidepressant prescription was classified as a nonspecialist, such as a general practitioner, family practitioner, or general internal medicine practitioner; a nonpsychiatric specialist, such as a cardiologist, gastroenterologist, or neurologist; or a psychiatrist.

For analyses of subtherapeutic dosing, the same specialty classifications were used, but analyses were based on all antidepressant prescriptions rather than on the index prescription only. Patients were classified into one of three groups—all prescriptions written by nonspecialists, at least one written by a specialist but none by a psychiatrist, or a least one written by a psychiatrist.

Analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows NT, version 7.5. In descriptive analyses, proportional differences were tested for statistical significance using Pearson's chi square test. Cost and age differences were tested using SPSS's medians test, which is nonparametric. Statistical tests of prescriber type compared psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists, instead of comparing all three types. The rationale for this approach was that the study's primary objective was to compare psychiatrists with other providers, not to compare different types of nonpsychiatric providers.

Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the impact of the prescriber's specialty on duration and dosage, controlling for the other independent variables. In these analyses, change in -2 times log likelihood, a goodness-of-fit measure with a chi square distribution, was used to test the models. Coefficient testing was performed using the Wald statistic. The significance level was set at .05.

Results

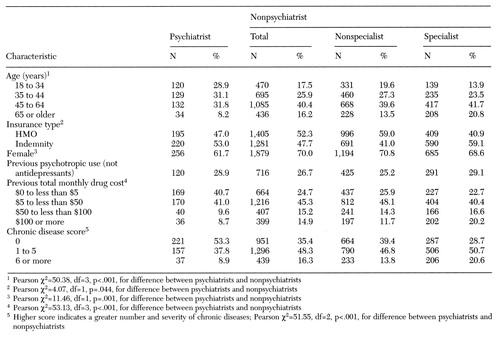

An overview of the study sample is shown in Table 1. Fifty-four percent of initial antidepressant prescriptions were written by nonspecialists, 32 percent by nonpsychiatrist specialists, and 13 percent by psychiatrists. The proportion of initial prescriptions written by specialists was lower in HMOs than in indemnity plans.

The median age of patients was 46 years, and 69 percent were women. Consistent with previous research (15,16), patients whose initial antidepressant prescription was written by a psychiatrist were younger, had lower costs for nonantidepressant drugs in the months before antidepressant treatment, and had lower rates of chronic disease than those whose initial prescription was written by a nonpsychiatrist. Median monthly drug costs for all medications before antidepressant treatment were $9 and $21 for patients treated by psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists, respectively (χ2 =49.3, df=1, p<.001). In addition, a smaller proportion of psychiatrists' patients were women. The proportions of psychiatrists' and nonpsychiatrists' patients with previous psychotropic use did not differ significantly, possibly because the sample was limited to patients who did not use antidepressants in the previous nine to 12 months.

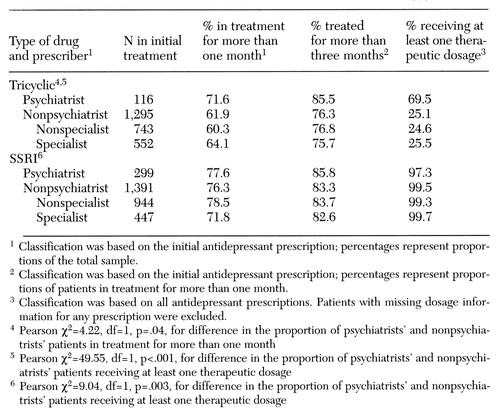

Table 2 provides an overview of the treatment course by drug type and type of prescriber. Each column represents the proportion of patients from the preceding column who achieved each milestone. For example, the rightmost column represents the proportion of patients from the adjacent column who received at least one therapeutic dosage. The rightmost column classifies patients according to their entire treatment course—that is, whether any SSRIs were taken and whether any prescriptions were written by a psychiatrist. The columns for patients in treatment for more than one month and for more than three months classify patients according to the drug and prescriber types for the index prescription only.

Among patients treated with tricyclics, 72 percent of those treated by psychiatrists continued treatment for more than one month, compared with 62 percent of those treated by nonpsychiatrists. Patients treated by psychiatrists were more likely to receive at least one therapeutic dosage than those treated by nonpsychiatrists (70 percent versus 25 percent).

In contrast, among SSRI-treated patients, one-month persistency rates were similar whether the initial prescription was by a psychiatrist or a nonpsychiatrist (78 and 76 percent, respectively). Similarly, rates of therapeutic dosing of SSRIs were 97 percent for patients with at least one antidepressant prescription from a psychiatrist and 100 percent for patients with no antidepressant prescriptions from a psychiatrist—a difference without substantive importance despite its statistical significance.

Thus when tricyclics were prescribed, patients treated by psychiatrists had higher rates of treatment persistency and dosage adequacy than those treated by nonpsychiatrists. These differences were not found when SSRIs were prescribed.

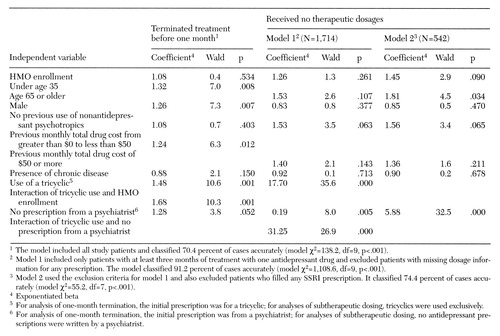

Logistic regression analyses assessed relationships between prescriber type, drug type, and treatment course, controlling for differences between psychiatrists' and nonpsychiatrists' patients in demographic characteristics and previous use of medications. The exponentiated beta coefficients shown in Table 3 represent the amount by which the odds of each of the two dependent variables—treatment termination and receiving no therapeutic dosages—were multiplied by each of the independent variables, controlling for the other independent variables. For example, the coefficient of 1.32 for age younger than 35 years in the termination equation indicates that the odds of termination were multiplied by 1.32, or increased by 32 percent, for a patient in the younger age group relative to older patients.

Additional significant predictors of one-month termination included male gender (26 percent increase in odds), a monthly drug cost before antidepressant therapy greater than 0 and less than $50 (24 percent increase), initial treatment with a tricyclic instead of an SSRI (48 percent increase), and the interaction of tricyclic use with HMO enrollment (68 percent increase). When the analysis controlled for these factors as well as other factors in the model (HMO enrollment, absence of previous psychotropic drug use, and presence of chronic disease), receiving the initial antidepressant prescription from a nonpsychiatrist was associated with a 28 percent increase in the odds of one-month termination. A term for interaction of tricyclic use with a nonpsychiatrist prescriber was tested, but it was not significant.

Analysis of subtherapeutic dosing used two models, each of which controlled for drug type in a different way. A factor for exclusive use of tricyclics was included in model 1 (see Table 3). This factor was coded 0 if the patient filled any SSRI prescriptions (including patients who used SSRIs exclusively) and coded 1 if the patient's antidepressant use was limited to tricyclics. In model 2, data for patients taking SSRIs were excluded from the analysis, so the equation was calculated for tricyclic-treated patients only.

In model 2, being age 65 or older was a significant predictor of subtherapeutic dosing. When the analysis controlled for age, as well as the other independent variables (HMO enrollment, male gender, absence of previous psychotropic use, previous monthly drug cost, and presence of chronic disease), receiving antidepressant prescriptions exclusively from nonpsychiatrists multiplied the odds of subtherapeutic dosing by a factor of 5.88 (a 488 percent increase in odds) for patients treated exclusively with tricyclics (model 2). Similarly, in model 1, the interaction of tricyclic use with nonpsychiatrist prescribers multiplied the odds of subtherapeutic dosing by a factor of 31.3.

Discussion and conclusions

Limitations

The most important limitation of this study is the observational design, which prohibits attributing causality to the findings. Given previous research documenting greater severity of depression among patients of psychiatrists than among patients of nonpsychiatrists (15,16), of particular concern is the possibility that psychiatrists' patients were treated more intensively because they were more acutely ill. Mitigating this problem was the exclusion of patients using antidepressants before the index date, the intent of which was to remove from the sample patients with chronic depression, treatment-resistant depression, or frequently recurring depression (15,16). In this context, it is important to note that the proportions of patients in this study with previous use of nonantidepressant psychotropic medications did not differ by provider type. Also mitigating the nonexperimental design was the use of logistic regression to control for differences in demographic characteristics and previous use of medications.

Another limitation arises because pharmacy claims do not contain diagnostic information. It is possible that differences between patients treated with tricyclics and those treated with SSRIs are attributable to the use of tricyclics for nonpsychiatric disorders such as migraine, chronic pain, or peripheral neuropathy. However, sensitivity analyses excluding data for patients who used antimigraine and pain medications intermittently or chronically (six or more prescriptions in the 25-month observation period) produced findings that were similar and in fact slightly stronger. Using these analyses, rates of one-month treatment persistence among tricyclic-treated patients were 72 percent for patients of psychiatrists and 57 percent for patients of nonpsychiatrists, and rates of therapeutic dosing were 76 percent for patients with at least one prescription from a psychiatrist and 25 percent for those with no prescriptions from a psychiatrist. Moreover, previous comparisons of patients treated with tricyclics and with SSRIs have produced similar findings for treatment persistence and therapeutic dosing, whether limited to individuals diagnosed with depression (8,9,11,17) or not (2,10).

Finally, the study included no direct measure of patient outcome, such as change in depressive symptoms. It is possible that the symptoms of some patients responded to dosages below the standards used in this study (18,19). However, there is no reason to suspect that these patients would be concentrated in the practices of any particular type of prescriber, which suggests a minimal impact on findings.

Implications

Course of antidepressant treatment is associated with both drug type and prescriber type. In multivariate equations, the effects of these two factors were independent when termination of treatment at one month was analyzed, and interactive when subtherapeutic dosing was analyzed. These findings suggest that both drug type (antidepressant selection) and prescriber type (specialty availability and utilization) should be considered, independently and jointly, when establishing treatment management policies. Although these findings are drawn from a large and diverse population, they are not definitive because of the study's observational design. Therefore, any consideration of policy implications must be framed as a discussion of areas for future research.

Until recently, discussions about improving the adequacy of antidepressant treatment identified essentially two arenas for potential change. Although interrelated, they can be separately categorized as organizational policy and provider behavior. Organizational policies that have been proposed or tested include better systems of referral between primary care and psychiatry, consultation-collaboration programs, and on-site access to psychiatrists in primary care settings (6,7,20,21,22,23,24,25). Provider changes include physician education programs, regular use of psychiatric diagnostic screening tools in primary care, and increased provider time spent educating patients about depression, its treatment, and medication side effects (6,21,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32).

To these areas of focus, a third has been recently added—the use of a particular antidepressant drug class. Several observers have argued that increasing the first-line use of SSRIs might improve treatment outcomes (12,33,34,35,36). This debate and the findings of this study raise important questions for future research in two major areas. First, randomized trials of the interactive effects of drug type and prescriber type on patient outcomes should be conducted to confirm our findings and to guide decisions about both specialty referral policies and drug formularies. An important related topic is whether formulary policies that restrict SSRI use and organizational arrangements that influence the accessibility of psychiatric services—for example, carve-outs versus consultation-liaison programs—interact in their effects on treatment outcomes.

Second, additional research is needed to document and, if possible, quantify cost offset effects, such as a reduction in office visits, that may be attributable to use of newer and more expensive antidepressant drugs. To date, studies of cost offsets have been limited to a few settings or to select patient groups (11,17,37,38,39). Elucidating the relationships between antidepressant selection and patient outcome across a variety of clinical settings is critical to setting effective treatment management policies in health care organizations.

First-Person Accounts Invited for Column

Patients, former patients, family members, and mental health professionals are invited to submit first-person accounts of experiences with mental illness and treatment for the Personal Accounts column of Psychiatric Services. Maximum length is 1,600 words. The column appears every other month.

Material to be considered for publication should be sent to the column editor, Jeffrey L. Geller, M.D., M.P.H., at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, Massachusetts 01655. Authors may publish under a pseudonym if they wish.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the intellectual contributions of Gretchen Engquist, Ph.D., and Marija J. Norusis, Ph.D. The authors also thank Suzanne Graden, R.Ph., Ruth Martinez, R.Ph., Andy Parker, M.B.A., and Trey Springer, C.Ph.T., who provided extensive assistance with data collection and the literature review. Brenda Motheral, Ph.D., provided helpful comments. This research was partly supported by a grant from SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals.

Ms. Fairman is outcomes research manager and Dr. Teitelbaum is vice-president and director of analysis and reporting in the health management services department of Express Scripts/ValueRx, Inc., which is based in Maryland Heights, Missouri. Dr. Drevets is associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Kreisman is director of adult services in the department of psychiatry at DePaul Health Center in St. Louis. Send correspondence to Ms. Fairman at Express Scripts/ValueRx, Inc., 1700 North Desert Drive, Tempe, Arizona 85281. This paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 17-22, 1997, in San Diego.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 3,101 adults who received a prescription for an antidepressant medication, by type of prescriber

|

Table 2. Course of treatment among 3,101 adult patients receiving a tricyclic antidepressant or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), by type of prescriber

|

Table 3. Logistic regression analyses of key treatment indicators among 3,101 adults who received a prescription for an antidepressant medication

1. Regier DA, Hirschfeld RMA, Goodwin FK, et al: The NIMH Depression Awareness, Recognition, and Treatment Program: structure, aims, and scientific basis. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1351-1357, 1988Link, Google Scholar

2. Katon W, VonKorff M, Lin E, et al: Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Medical Care 30:67-76, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, et al: Treatment received by depressed patients. JAMA 248:1848-1855, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, et al: Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:458-466, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wells KB, Katon W, Rogers B, et al: Use of minor tranquilizers and antidepressant medications by depressed outpatients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:694-700, 1994Link, Google Scholar

6. Katon W, VonKorff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026-1031, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Katon W, VonKorff M, Lin EH, et al: A randomized trial of psychiatric consultation with distressed high-utilizers. General Hospital Psychiatry 14:86-98, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Jefferson JW, et al: Prescribing patterns of antidepressant medications for depression in a HMO. Formulary 31:374-388, 1996Google Scholar

9. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Wagner EH, et al: Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:399-408, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Fairman KA, Teitelbaum F, Drevets WC, et al: Course of antidepressant treatment with tricyclic versus selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor agents: a comparison in managed care and fee-for-service environments. American Journal of Managed Care 3:453-465, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

11. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Heiligenstein JH, et al: Initial antidepressant choice in primary care: effectiveness and cost of fluoxetine versus tricyclic antidepressants. JAMA 275:1897-1902, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Thompson C: Bridging the gap between psychiatric practice and primary care. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 7(suppl 2):31-36, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

13. Physicians' Desk Reference: Generics. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics, 1995Google Scholar

14. VonKorff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K: A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 45:197-203, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Cooper-Patrick L, Crum RM, Ford DE: Characteristics of patients with major depression who received care in general medical and specialty mental health settings. Medical Care 32:15-24, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wells KB, Burnam MA, Camp P: Severity of depression in prepaid and fee-for-service general medical and mental health specialty practices. Medical Care 33:350-364, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sciar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL, et al: Antidepressant pharmacotherapy: economic outcomes in a health maintenance organization. Clinical Therapeutics 16:715-730, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

18. American Psychiatric Association Task Force on the Use of Laboratory Tests in Psychiatry: Tricyclic antidepressants: blood level measurements and clinical outcome: an APA task force report. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:155-162, 1985Link, Google Scholar

19. Preskorn SH, Fast GA: Therapeutic drug monitoring for antidepressants: efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 52(Aug suppl):23-33, 1991Google Scholar

20. Katon W, Gonzales J: A review of randomized trials of psychiatric consultation-liaison studies in primary care. Psychosomatics 35:268-278, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Brody DS, Larson DB: The role of primary care physicians in managing depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 7:243-247, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Eisenberg L: Treating depression and anxiety in primary care: closing the gap between knowledge and practice. New England Journal of Medicine 326:1080-1084, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Goldberg RJ: Psychiatry and the practice of medicine: the need to integrate psychiatry into comprehensive medical care. Southern Medical Journal 88:260-267, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hirschfeld RMA, Keller MB, Panico S, et al: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 277:333-340, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Wells KB, Sturm P: Care for depression in a changing environment. Health Affairs 14 (3):78-89, 1995Google Scholar

26. Anderson SM, Harthorn BH: Changing the psychiatric knowledge of primary care physicians: the effects of a brief intervention on clinical diagnosis and treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry 12:177-190, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, et al: Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42:839-846, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Fawcett J: Compliance: definitions and key issues. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56(Jan suppl):4-8, 1995Google Scholar

29. Gerber PD, Barrett JE, Barrett JA, et al: The relationship of presenting physical complaints to depressive symptoms in primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 7:170-173, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Kessler LG, Cleary PD, Burke JD: Psychiatric disorders in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:583-587, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lin EHB, VonKorff M, Katon W, et al: The role of the primary care physician in patients' adherence to antidepressant therapy. Medical Care 33:67-74, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Robinson P, Bush T, VonKorff M, et al: Primary care physician use of cognitive behavioral techniques with depressed patients. Journal of Family Practice 40:352-357, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

33. Andrews JM, Nemeroff CB: Contemporary management of depression. American Journal of Medicine 97(suppl 6A):24S-32S, 1994Google Scholar

34. Heiligenstein JH: Reformulating our formularies to reflect real-world outcomes. Drug Benefit Trends 8(8):35,42, 1996Google Scholar

35. Stokes PE: Fluoxetine: a five-year review. Clinical Therapeutics 15:216-243, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

36. Zetin M, Hansen J: Rational antidepressant selection. Comprehensive Therapy 20:209-223, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

37. Skaer TL, Sclar DA, Robison LM, et al: Economic valuation of amitriptyline, desipramine, nortriptyline, and sertraline in the management of patients with depression. Current Therapeutic Research 56:556-567, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Smith W, Sherrill A: A pharmacoeconomic study of the management of major depression: patients in a TennCare HMO. Medical Interface 9(7):88-92, 1996Google Scholar

39. Thompson D, Buesching D, Gregor KJ, et al: Patterns of antidepressant use and their relation to costs of care. American Journal of Managed Care 2:1239-1246, 1996Google Scholar