Family Caregivers' Criticism of Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Relationships were examined between patients' negative symptoms, family caregivers' knowledge of schizophrenia, caregivers' attributions about the cause of patients' symptoms, and caregivers' response to the symptoms. METHODS: A sample of 84 caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in Brisbane, Australia, were interviewed using a structured format and measures designed for the study. RESULTS: Results of regression analyses indicated that three variables significantly predicted caregivers' criticism of patients—a smaller proportion of negative symptoms in the patient's overall symptom pattern, the caregiver's low level of knowledge about the illness, and the caregiver's attributing the cause of negative symptoms to the patient's personality rather than to the illness. CONCLUSIONS: Overall, findings supported the utility of an attributional framework in enhancing conceptions about and research on schizophrenia and family caregiving.

A considerable body of evidence now exists to suggest that family environment may exert a significant influence on the course of schizophrenia. In particular, several studies of expressed emotion, a measure that reflects the amount of caregivers' criticism toward or emotional overinvolvement with patients, have shown that when patients return to family environments with high levels of expressed emotion, they are at least three times more likely to relapse than patients returning to family environments with low levels of expressed emotion (1,2,3,4,5).

"High expressed emotion" has come to be used to describe families clinically, and treatment decisions may be made on the basis of the family's being perceived in this way and therefore as noxious for the patient. This situation exists despite the fact that the literature on expressed emotion is plagued with unanswered questions. For example, it is still unclear exactly what is being measured by the construct of expressed emotion, why some families have high levels of expressed emotion and others do not, and by what mechanisms a high level of expressed emotion influences patients' outcomes. Constructs such as expressed emotion should have practical implications for the management and care of patients with schizophrenia. However, preoccupation with the link between expressed emotion and relapse has hindered a thorough investigation of the factors that may influence the level of expressed emotion among family caregivers.

In an attempt to explain expressed emotion, some studies have concentrated on differences between caregivers. For example, people with a high level of expressed emotion might be more socially isolated (6,7), or cope less effectively (8,9,10,11), or have less knowledge of the illness (1,5). In fact, a lack of understanding about mental illness has been proposed as a major source of high levels of expressed emotion, and most family intervention programs include an educational component (12,13,14). The underlying assumption is that giving caregivers information about the nature of the disorder can improve their coping effectiveness, lower frustration, and lessen their tendency to be critical (15).

Other researchers have proposed that a high level of expressed emotion may be a reaction to patients' behavior or reflect an interactive process (16,17,18,19). Several studies have attempted to explore the relationship between patients' behaviors and caregivers' expressed emotion (1,20,21,22). The findings of earlier work (1,20) cast doubt on the importance of variables related to the illness in explaining caregivers' expressed emotion. However, these studies largely ignored the negative symptoms of the disorder and did not report whether patients' disturbance varied across types of high expressed emotion—that is, criticism versus overinvolvement. Thus any effects attributable to patient variables may have been inadvertently disguised in these early studies. In support of this contention, Vaughn (23) reported that caregiver criticism is associated with patients' long-standing social impairment, and other research has shown that caregivers find negative symptoms of particular concern (24).

Taken together, these findings suggest that attempts to understand expressed emotion must take into account the interrelationships among patient and caregiver variables (25). In keeping with such an approach to understanding expressed emotion, it has been suggested that the attributions caregivers make about the causes and controllability of disturbed behavior in their ill family member may be important in understanding their response to the patient. Several authors have speculated that attributing symptoms to the patient rather than the illness is related to high expressed emotion among caregivers (5,26,27,28). Others go further to suggest that negative symptoms, such as apathy, social withdrawal, and poor personal hygiene, tend to be perceived by caregivers to be more controllable by the patient than are positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, and are thus more likely targets for caregivers' criticism (29).

According to attribution theory (30), particular emotions are related to attributional dimensions. For example, it has been proposed that anger toward another person is experienced when a negative outcome is attributed to a cause controllable by that person (30). Attribution theory has been applied for many years, in such areas as marital distress (31,32) and parent-child interactions associated with risk for abuse (33,34,35). However, studies by Brewin and associates (36) and Harrison and Dadds (37) are among the very few studies that have examined attributions of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia.

Although these studies used different strategies to measure attributions, their findings were quite similar. Brewin and associates (36) found that caregivers' attributions varied considerably across patient behaviors, and that the type of attribution was associated with the emotional attitude of the caregiver toward the patient. That is, when caregivers perceived the causes of behaviors as more personal to and controllable by the patient (internal attribution), they were more likely to be critical. Harrison and Dadds (37) found that critical caregivers were more likely to attribute negative symptoms to the personality of the patient than caregivers with low expressed emotion or emotionally overinvolved caregivers. Furthermore, knowledge of the illness was negatively correlated with internal attributions.

In addition, both studies reported that emotionally overinvolved caregivers tended to make the largest number of external attributions—that is, attributions to the illness rather than to the patient. This finding is broadly consistent with Hooley's earlier speculation (28) that caregivers with low expressed emotion and emotionally overinvolved caregivers would make similar causal attributions.

What these two studies highlight, apart from the utility of examining caregivers' attributions, is the necessity of studying the relationship between the components of expressed emotion, especially criticism, and the different symptoms of schizophrenia. The practice of applying the dichotomous labels of high versus low expressed emotion may have disguised important within-group differences in several earlier studies (24) and may have limited the type of statistical analyses conducted. In the original development of the Camberwell Family Interview, the criticism and emotional overinvolvement scales were seen as independent, and subsequent research has shown low to moderate intercorrelations between the scales (38).

Finally, if we accept the link between expressed emotion and relapse, it is important that we understand what the expressed emotion construct is measuring. Several key variables have been identified that may explain why some caregivers respond negatively to their patients and others do not; quality of patients' symptoms, caregivers' knowledge, and caregivers' attributions are among the most prominent variables. However, no study to date has examined the interrelationships among all of these variables. Variables related to patients' illness have not always been independently assessed, nor has expressed emotion been operationalized as a dependent measure. Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the relative importance of particular caregiver or patient effects as predictors of levels of expressed emotion.

This study worked within an attributional framework that assumes that patient and caregiver variables elicit caregivers' response. Three variables were hypothesized to be associated with higher levels of criticism among caregivers—patients' greater proportion of negative symptoms (as opposed to positive symptoms), the caregiver's low level of knowledge of the illness, and the caregiver's tendency to attribute negative symptoms to the patient (internal causal attributions) rather than to the illness (external causal attributions).

Methods

Sample

Participants were recruited through several psychiatric hospitals and clinics in Brisbane, Australia, over two and a half years (February 1990 to August 1992). To be selected for the study, the participant had to be the major caregiver of a patient with schizophrenia, reside in the Brisbane metropolitan area, be living in the same residence with the patient, be English speaking, have no history of major mental illness, and be willing to participate. All patients had received a DSM-III-R diagnosis (39) of schizophrenia.

Although data on interrater reliability for the DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia were unavailable, a rigorous diagnostic procedure was used. An initial interview was conducted with the patient to assess mental state and to gather information on the reason for admission or referral, history of illness, treatment history, medical history, and personal history, including childhood health problems, work record, drug and alcohol use, family relationships, legal problems, and financial circumstances. Data were also obtained from the patient's general practitioner, past hospital discharge summaries, family members, and significant others. The patient was then observed over time to assess changes in mood and behavior and response to treatment such as medication or therapy. A tentative diagnosis of schizophrenia was given by the psychiatrist if all information gathered about the mood and behavior of the patient currently and for at least the past six months was consistent with DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia.

However, to verify the psychiatrist's decision, the patient's case history was then presented to a multidisciplinary team of clinical psychologists, psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists, and social workers. When consensus on diagnosis was reached, a firm diagnosis of schizophrenia was given, and the patient was eligible to be included in the study. If consensus was not forthcoming, the diagnosis was withheld pending further assessment, and the patient was considered ineligible for the study.

After the patient's consent was obtained, potential caregiver participants were contacted by hospital and clinic staff to ask whether they were willing to be interviewed by the researcher. A brief description of the study was provided. Of the 120 caregivers contacted, 94 agreed to be interviewed, and 84 were subsequently recruited, when a mutually suitable time and place to be interviewed was arranged.

Procedure

Caregivers were interviewed by the first author using a structured interview schedule lasting approximately two hours. The schedule was administered in the same order to each participant and contained instruments to measure caregivers' knowledge of the illness, their causal attributions about patients' symptoms, and their response to the symptoms. Within two weeks of interviewing the caregiver, a medical assessment of the patient was obtained from the patient's treating psychiatrist to gather information on the patient's level of negative symptoms.

Measures

Knowledge of the illness was measured using a questionnaire developed for the study. Preliminary findings reported elsewhere (37) indicated that knowledge as measured by this instrument reliably discriminates between different types of expressed emotion. That is, higher levels of knowledge are related to lower levels of criticism. The content of the measure is quite similar to that mentioned in previous studies (13,14,40). Six items asked about diagnosis, treatment, the nature of the patient's illness, and prognosis. Caregivers were asked to name the patient's illness, to identify three symptoms of the illness and what forms of treatment were currently used, to identify helpful and unhelpful circumstances for the patient, and to describe their understanding of the future for someone with the illness.

If insufficient or unclear information was given by the respondent, the examiner gave up to three prompts, asking "Can you tell me more?" or "Is there anything you would like to add?" Responses were written verbatim by the examiner, and audiotaping allowed later verification of responses. The responses were scored by an independent rater using a scoring key that indicated points for particular responses.

A list of "acceptable" responses about symptoms of the illness was based on DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria. Current research and clinical practice guided the selection of acceptable responses to questions about current treatment, helpful and unhelpful circumstances for patients, and prognosis. A total knowledge score was obtained by summing the correct responses on each of six questions, with 15 being the highest possible total score. A second administration of this test to nine of the caregivers in the study indicated good test-retest reliability (r=.83).

Caregivers' attributions were measured using the Attributions of Symptoms Inventory (37). From a list of 18 symptoms (12 negative and six positive symptoms), caregivers were asked to indicate whether each symptom had occurred. If the symptom had occurred, the caregiver was then asked, "What, in your opinion, causes this behavior?" When a response was given, the examiner then followed up with, "So, would you say the cause is illness, personality or nature of the patient, or something else?" The second question was an attempt to avoid forcing the participants too early into a choice of cause. However, its use was often redundant because caregivers tended to automatically categorize their causal attribution. The percentage of negative symptoms attributed to personality was obtained for each participant.

The Attributions of Symptoms Inventory has successfully been used in previous studies with caregivers of patients with schizophrenia (37). The instrument was administered on two occasions approximately six weeks apart to nine of the caregivers in this study to examine its stability over time. Pearson product-moment correlations were used to calculate reliability coefficients. For occurrence of symptoms the coefficient (r) was .68 (p<.05), for percentage of symptoms attributed to illness it was .90 (p<.01), for percentage of negative symptoms attributed to personality it was .76 (p<.05), and for percentage of positive symptoms attributed to personality it was .91 (p<.01). Given the small sample used for this analysis, these results indicate adequate test-retest reliability.

The Attributions of Symptoms Inventory was developed because no suitable instrument existed that would allow for direct scoring (as opposed to content analyses) of causal attributions. An initial list of 40 positive and negative symptoms was derived by combining frequently occurring items on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (41), Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (42), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (43), Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version (44), and the Current and Past Psychopathology Scales (45). All of these measures are widely used by psychologists and psychiatrists in clinical settings. In wording the items, particular attention was given to using jargon-free language.

Although our scale was developed independently, the final composition of symptoms was quite similar to that used by others (46,47). To validate the specific symptoms to be used in this inventory, the list of 40 symptoms was presented to 20 mental health professionals with more than five years of experience. They were asked to state whether each was a symptom of schizophrenia, and if so, whether it was a positive symptom (behavioral excess) or a negative symptom (behavioral deficit) of the disorder. Only items on which rate of interrater agreement was greater than 70 percent were included in the final version of the scale.

The measure was then administered to the psychiatrists and caregivers of the patients in this study, and the only symptoms included in the final scale were those experienced by more than 60 percent of the patients in the previous year, those that were adequately distributed in the sample, and those that had adequate intercorrelations among negative and positive symptoms. As noted above, the final list of 18 symptoms included 12 negative and six positive symptoms. Examples of descriptions of negative symptoms were "shows little emotion," "no attention to appearance," "slow in completing tasks," and "avoids contact with others."

Information about each patient's pattern of negative symptoms was obtained by asking the patient's treating psychiatrist to indicate the occurrence over the last year of the 18 symptoms from the Attributions of Symptoms Inventory. Psychiatrists' responses about patients' symptoms were verified by consulting patients' charts and by discussions with caregivers. Thus a total number of symptoms for each patient was calculated, and from this total the percentage of symptoms that were of a negative type was obtained. The percentage of symptoms was used in preference to the absolute number of negative symptoms to reflect differences among patients in the quality of symptoms.

Caregivers' response to patients was measured by the number of criticisms expressed, which was taken from content analyses of Five Minute Speech Sample (FMSS) audiotapes. The FMSS, developed by Magana and associates (48), is a reliable measure of expressed emotion, providing ratings comparable to the well-validated original measure of expressed emotion, the Camberwell Family Interview (19,49). Caregivers are asked to speak for a few minutes about the patient, what kind of person the patient is, and how the two of them get along together. The tape recorded speech samples were scored and analyzed using Magana's criteria (48) by a trained independent rater who was blind to the purpose of the study.

Based on specific criteria, the FMSS divides expressed emotion into four categories—critical and emotionally overinvolved, critical only, emotionally overinvolved only, and low expressed emotion. However, because we were operationalizing expressed emotion as a dependent measure in this study, the number of criticisms made by caregivers was of major interest. Interrater reliability was tested on 35 percent of the tapes (N=30), which resulted in a kappa of .80. Test-retest reliability coefficients for all components of expressed emotion ranged from .29 for statements of attitude to 1 for emotional display, with good reliability for the number of criticisms (r=.71), which was the component of expressed emotion used in this study.

Results

Preliminary analyses

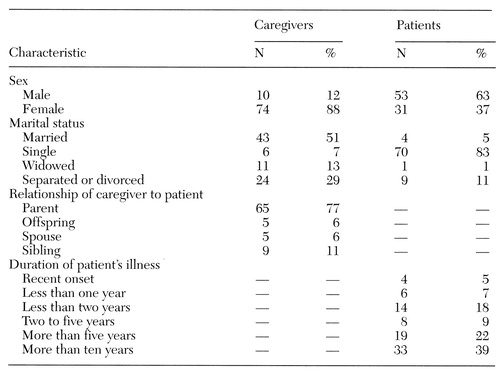

The final sample comprised 84 caregivers of predominantly chronic patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Table 1 summarizes characteristics of caregivers and their patients, including sex, marital status, relationship of caregiver to patient, and duration of illness. Most caregivers were women, most were married, and most were patients' mothers. The mean age of the caregivers was 52.2 years, with a range of 16 to 77 years.

Of the 84 patients in the study, most were male (Table 1) and lived with their parents. Their mean age was 31 years, with a range of 15 to 85 years. Patients' mean age at first hospitalization was 23.69 years, with a range of 15 to 71 years. The mean number of hospital admissions was 5.63, with a range of no admissions to 27 admissions. At the time of the interview with the caregiver, 42 patients were in the hospital, 18 had been recently discharged, and 24 were outpatients of clinics or hospital day centers.

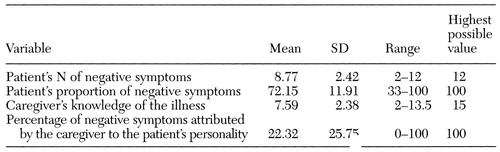

Preliminary diagnostics were done on each variable using the SPSS-X FREQUENCIES program to screen the data for violations of normality. Deriving means and standard deviations gave information on variance in the data, and the resulting scatter plots allowed checks on outliers and linearity of the data. Summary statistics for all patient and caregiver variables are shown in Table 2.

To examine the interrelationships among the independent variables and to check for multicolinearity, correlational analysis was performed. Correlational analyses indicated that a caregiver's knowledge of the illness was negatively correlated with the percentage of negative symptoms attributed to personality (r=-.23, p<.05). Thus when caregivers had little knowledge, they were more likely to attribute negative symptoms to the patient rather than to the illness. No other significant correlations were found among the patient and caregiver variables.

Major analyses

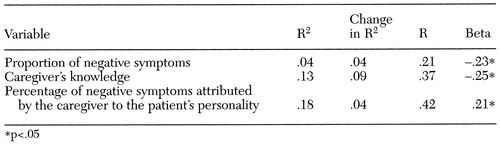

We used hierarchical multiple regression analysis to test the relationship between the number of criticisms as the dependent variable and three independent variables—the proportion of negative symptoms, caregivers' knowledge, and the percentage of negative symptoms attributed to the patient's personality. The results presented in Table 3 indicate that the three predictor variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in the number of criticisms (R=.42, R2=.18, F=5.69, df=3,80, p<.01). The proportion of negative symptoms and caregivers' knowledge were significantly negatively related to the number of criticisms. The percentage of negative symptoms attributed to personality was positively related to the number of criticisms. Thus when the proportion of negative symptoms was smaller than the proportion of positive symptoms and when caregivers knew little about the illness and attributed negative symptoms to the personality of the patient rather than to the illness, caregivers were more likely to be critical of the patient.

Discussion and conclusions

The results partly confirmed the hypothesis that the proportion of negative symptoms and caregivers' knowledge and attributions would predict a critical response among caregivers. It was found that when the patient's proportion of negative symptoms was relatively small, and caregivers had little knowledge of the illness and attributed the cause of negative symptoms to the patient (internal attribution), caregivers were more likely to be critical of the patient. The set of three predictor variables accounted for a moderate amount of the variance in caregivers' critical response, and all three significantly contributed to the overall result.

Contrary to expectation, caregivers' critical response was associated with a smaller proportion of negative symptoms rather than a larger one. That is, the lower the proportion of negative symptoms in the patient's pattern of positive and negative symptoms, the more likely the caregiver was to be critical of the patient. One possible explanation is that when a patient has a large number of positive symptoms, a small number of negative symptoms is less likely to be viewed as part of the same illness. Rather, the relatively few negative symptoms may be more likely to be viewed as part of the patient's personality or reaction to the illness and therefore under the patient's control. Further research is needed to clarify this finding. Previous studies have tended to focus on the effect of negative symptoms on caregivers rather than considering symptom profiles (24).

An alternative explanation for this finding may be methodological problems with use of the FMSS. Even highly critical caregivers can make only a few criticisms in five minutes.

Findings in this study were consistent with attribution theory in general—that is, when internal attributions of behavior are made, a negative response is more likely. More specifically, our findings support the speculation of many authors (5,26,(27,28), as well as the findings of two previous studies (36,37), that patients' symptoms elicit criticism from caregivers who perceive the cause of the symptoms as internal to the patient and therefore perceive the patient as able to control the symptoms.

Knowledge of the illness was found to be negatively related to internal attributions. That is, the more knowledge caregivers had about the illness, the less likely they were to make internal attributions. This finding supports the inclusion of an educational component in family intervention programs. Giving information to caregivers about schizophrenia increases their coping effectiveness and lessens their tendency to be critical (15). The results also support the point made by Brewin and colleagues (36) that the mechanism behind existing intervention packages that concentrate on reducing high expressed emotion (50,51) may be some kind of attribution retraining. However, initial and postintervention assessments of attributions and knowledge will be required to examine these interrelationships. Certainly, the inclusion of more direct work on causal attributions in family intervention programs to facilitate emotional and behavioral change (52) is warranted.

Because this study focused on negative symptoms, no firm conclusions can be drawn about the differential effects of positive and negative symptoms and their relationship to criticism. However, results of preliminary work indicated that caregivers more often make internal attributions about negative symptoms (37), and thus they are more likely to be associated with a critical response. Future studies would do well to report on both positive and negative symptoms.

In this study the construct of caregivers' response was intentionally limited to criticism. Future studies should measure a range of responses—for example, pity, guilt, and ignoring—to provide a more comprehensive view of caregivers' response. Although there is little doubt that some caregivers respond with criticism to their relatives with schizophrenia, other caregivers do not. In this study a symptom pattern characterized by a small proportion of negative symptoms, a low level of caregivers' knowledge of schizophrenia, and a high level of internal causal attributions about patients' negative symptoms accounted for a moderate amount of variance in predicting caregivers' criticism of patients.

New Compendium Highlights Strategies for Assessing Outcomes of Treatment

A compendium of 12 articles on assessing patients outcomes in mental health treatment originally published in Psychiatric Services was recently released by the Psychiatric Services Resource Center.

Entitled Outcomes Assessment In Mental Health Treatment, the 72-page compendium in intended to serve as a useful resource document for mental health professionals grappling with the problems and possibilities of outcomes assessment systems.

The compendium includes articles that delineate the major principles of outcomes assessment, discuss key issues that must be addressed in planning an outcomes management system, and compare outcomes of different treatment approaches. Other articles report the results of using various outcomes measures with specific populations, focus on the selection of outcomes indicators, and examine the utility of various indicators as predictors of outcome.

A copy of the compendium has been sent to mental health facilities enrolled in the Psychiatric Services Resource Center. Single copies, regularly priced at $13.95, are $8.95 for staff in Resource Center Facilities For ordering information, call the resource center at 800-366-8455 or fax a request to 202-682-6189.

Dr. Harrison is lecturer in clinical psychology and Dr. Smith is reader in psychology at the School of Psychology of the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia 4072 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Dadds is professor of clinical psychology at Griffith University in Brisbane.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 84 family caregivers and the patients with schizophrenia they cared for

|

Table 2. Mean values for variables measured among 84 caregivers and patients with schizophrenia

|

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis of the relationship of the proportion of negative symptoms,caregiver's knowledge, and caregiver's attributions to the caregiver's critical response

1. Brown GW, Birley JLT, Wing JK: Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders: a replication. British Journal of Psychiatry 121:241-258, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Karno M, Jenkins JH, De la Selva A, et al: Expressed emotion and schizophrenic outcome among Mexican-American families. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 175:143-151, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Leff J, Wig NN, Ghosh A, et al: Influence of relatives' expressed emotion on the course of schizophrenia in Chandigarh. British Journal of Psychiatry 151:166-173, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Moline RA, Singh S, Morris A, et al: Family expressed emotion and relapse in schizophrenia in 24 urban American patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1078-1081, 1985Link, Google Scholar

5. Vaughn CE, Leff JP: The influence of family and social factors on the course of psychiatric illness: a comparison of schizophrenic and depressed neurotic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 129:125-137, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Anderson C, Hogarty G, Bayer T, et al: Expressed emotion and social networks of parents of schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 144:247-255, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Brown GW, Monck EM, Carstairs GM, et al: Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic illness. British Journal of Preventative Social Medicine 16:55-58, 1962Google Scholar

8. Birchwood M, Cochrane R: Families coping with schizophrenia: coping styles, their origins and correlates. Psychological Medicine 20:857-865, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hatfield AB: Coping effectiveness in families of the mentally ill: an exploratory study. Journal of Psychiatric Treatment and Evaluation 3:11-19, 1981Google Scholar

10. Hooley JM: Expressed emotion: a review of the critical literature. Clinical Psychology Review 5:119-139, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Kuipers L, Bebbington P: Expressed emotion research in schizophrenia: theoretical and clinical implications. Psychological Medicine 18:893-909, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Berkowitz R, Eberlein-Vries R, Kuipers L, et al: Educating relatives about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:418-429, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. McGill CW, Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, et al: Family educational intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:934-938, 1983Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Pakenham KI, Dadds MR: Family care and schizophrenia: the effects of a supportive educational program on relatives' personal and social adjustment. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 21:580-590, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hatfield AB, Spaniol L, Zipple AM: Expressed emotion: a family perspective. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:221-226, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Cook WL, Kenny DA, Goldstein MJ: Parental affective style risk and the family system: a social relations model analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 100:492-501, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Glynn SM, Randolph ET, Eth S, et al: Patient psychopathology and expressed emotion in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:877-880, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Falloon IRH: Premorbid and symptomatic characteristics of schizophrenics from families with high and low levels of expressed emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 92:359-367, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Doane JA, et al: Is expressed emotion an index of a transactional process? I. parents' affective style. Family Process 28:153-167, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Leff JP: Schizophrenia and sensitivity to the family environment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2:566-574, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Falloon IRH, et al: Interactional correlates of expressed emotion in the families of schizophrenics. British Journal of Psychiatry 144:482-487, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Strachan AM, Feingold D, Miklowitz DJ, et al: Does expressed emotion index a transactional process? II. patients' coping style. Family Process 28:169-181, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Vaughn CE: Patterns of emotional response in the families of schizophrenic patients, in Treatment of Schizophrenia: Family Assessment and Intervention. Edited by Goldstein MJ, Hand I, Hahlweg K. Heidelberg, Springer-Verlag, 1986Google Scholar

24. Kanter J, Lamb HR, Loeper C: Expressed emotion in families: a critical review. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:374-380, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Falloon IRH: Expressed emotion: current status. Psychological Medicine 18:269-274, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Brewin CR: Cognitive Foundations of Clinical Psychology. London, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

27. Greenley JR: Social control and expressed emotion. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 174:24-30, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hooley JM: The nature and origins of expressed emotion, in Understanding Major Mental Disorder: The Contribution of Family Interaction Research. Edited by Hahlweg K, Goldstein MJ. New York, Family Process Press, 1987Google Scholar

29. Hooley JM, Richters JE, Weintraub S, et al: Psychopathology and marital distress: the positive side of positive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 96:27-33, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Weiner B: An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1986Google Scholar

31. Fincham FD, O'Leary KD: Causal inferences for spouse behavior in maritally distressed and nondistressed couples. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 1:42-57, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Jacobson NS, McDonald DW, Follette WC, et al: Attributional processes in distressed and nondistressed married couples. Cognitive Therapy and Research 9:35-50, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Bugental DB: Attributions as moderator variables within social interactional systems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 5:469-484, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Butler RJ, Brewin CR, Forsythe WI: Maternal attributions and tolerance for nocturnal enuresis. Behaviour Research and Therapy 24:307-312, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Larrance DT, Twentyman CT: Maternal attributions and child abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 92:449-457, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Brewin CR, MacCarthy B, Duda K, et al: Attribution and expressed emotion in the relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 100:546-554, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Harrison CA, Dadds MR: Attributions of symptomatology: an exploration of family factors associated with expressed emotion. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 26:408-416, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Leff J, Vaughn C: Expressed Emotion in Families: Its Significance for Mental Illness. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

39. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

40. Smith JV, Birchwood MJ: Specific and non-specific effects of an educational intervention with families living with a schizophrenic relative. British Journal of Psychiatry 150:645-652, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) for Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261-276, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Andreasen NC: The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

43. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Lewine RRJ, Fogg L, Meltzer HY: Assessment of negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 9:368-376, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: Current and Past Psychopathology Scales (CAPPS). Archives of General Psychiatry 27:678-687, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Creer C, Wing J: Living with a schizophrenic patient. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 14:73-83, 1975Google Scholar

47. Runions J, Prudo R: Problem behaviours encountered by families living with a schizophrenic member. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 28:382-386, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Magana AB, Goldstein MJ, Karno M, et al: A brief method for assessing expressed emotion in relatives of psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Research 17:203-212, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Hahlweg K, Goldstein MJ, Nuechterlein KH, et al: Expressed emotion and patient-relative interaction in families of recent onset schizophrenics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 57:11-18, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Leff J, Kuipers L, Berkowitz R, et al: A controlled trial of social intervention in the families of schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 141:121-134, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Vaughn C, et al: The community management of schizophrenia: a controlled trial of a behavioural intervention with families to reduce relapse. British Journal of Psychiatry 153:532-542, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Birchwood M: Familial factors in psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 5:295-299, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar