Rehab Rounds : Predicting Rehabilitation Outcome Among Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: Efforts to identify variables that predict outcomes among clients with serious and persistent mental illness span a quarter of a century (1,2,3). Within the realm of psychiatric rehabilitation, vocational performance has been the main outcome measure. For example, previous employment history has been found to be the best predictor of subsequent employment status (4). Most studies have found that the presence of psychotic symptoms predicts a negative vocational outcome, especially when symptoms and vocational status are measured concurrently (5,6,7). Mediating variables, such as a positive relationship between client and therapist and monetary incentives, have also been correlated with favorable vocational outcomes (8,9).In this month's column, Andrew Ferdinandi, Ph.D., and his colleagues at the Queens Day Center, a division of the Long Island Jewish Medical Center, venture off the beaten track of vocational performance by defining successful rehabilitation in other domains of community living such as socializing, learning, and developing independent living skills. The evaluation methodology used by the authors highlights the role of variables focused on subjective experience, in this case their clients' desire to make changes in their life circumstances, as an important predictor of rehabilitation outcomes. Thus to optimize the prediction of rehabilitation activities, the authors have merged their interest in objectively assessing community functioning with the subjective, self-stated goals of clients.

Although a few studies have examined the characteristics of persons with serious and persistent mental illness that correlate with vocational outcome (4,5,6,7,8,9), an untapped area of inquiry in predicting vocational success is an individual's readiness to make changes in his or her life (10). For example, some people may have their symptoms under control, successful life experiences, and intact social and independent living skills, but they are still unwilling to pursue job opportunities. Understanding the variability in subjective attitudes toward work and incorporating those attitudes into the overall clinical assessment may be essential for developing an individualized treatment and rehabilitation plan (11).

Furthermore, a focus on vocational endpoints may be too narrow a determinant of rehabilitative success. For example, few studies have addressed the academic, recreational, and interpersonal aspects of rehabilitation. Such an omission may underestimate the effectiveness of a rehabilitation program, unnecessarily constrict its comprehensiveness, and lessen the relevance of psychiatric rehabilitation for participants (12). Expanding outcome measures beyond vocational rehabilitation, to include a wider variety of domains where change can take place, may broaden clinicians' perspectives on the goals of psychiatric rehabilitation.

At the Queens Day Center, we have used rehabilitation readiness assessment, an eight-session, one-hour-a-week group intervention, to provide a forum for clients to explore their attitudes and capacities for improving their functioning across the spectrum of community endeavors. Each group consisted of six to eight participants who were capable of engaging in an interactive and didactic group process and who could, with staff guidance and support, make thoughtful decisions about their level of dissatisfaction and motivation to make changes in their life roles. This process accommodated participants with various levels of cognitive functioning.

At the end of eight weeks, participants met individually with the group leader, who evaluated them using the Overall Readiness Scale (13). The scale is divided into four content areas: living, learning, working, and socializing. Within each content area there are five categories: need for change, commitment to change, self-awareness, environmental awareness, and personal closeness. The need for change is defined operationally as the client's internal or external pressure to make a change and the time frame in which that change needs to take place. Commitment to change is defined as the degree to which the client believes change is positive, possible, and supported by his or her environment. Self-awareness is the ability to describe interests, values, and how choices were made in the past. Environmental awareness is the degree to which a client can talk about future environments in which he or she may want to get involved. Personal closeness is the positive or negative feelings that the client has toward the rehabilitation coordinator and the ability to work together toward the goal of assessing readiness. Each category is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of readiness to pursue change.

A pilot study was done to examine how well the Overall Readiness Scale predicted participants' actual change toward successful rehabilitation six months after they completed the rehabilitation readiness assessment group. Thirty-nine persons with schizophrenia were recruited from the continuing day treatment program. They joined the rehabilitation readiness assessment group after expressing an interest in rehabilitation or being referred by their case manager for assessment of rehabilitation readiness. All 39 subjects completed the eight sessions of the group intervention.

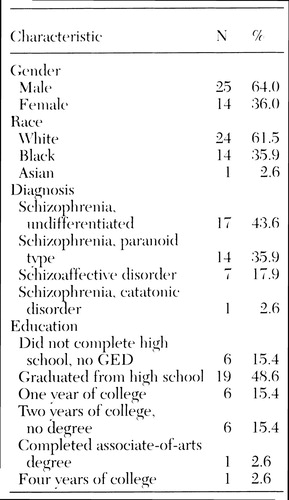

Besides the data obtained through the Overall Readiness Scale, data were collected on the participants' number of past psychiatric hospitalizations, age, and length of time in the current day treatment program. The mean age of the subjects was 36.1± 8.9 years, the mean number of past psychiatric hospitalizations was 2.5± 1.6, and the average length of time in the day treatment program was 44±16 months. Other demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

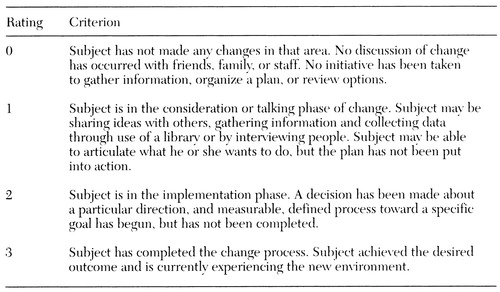

Six months after completing the scale, participants in the group were interviewed (32 in person and seven by telephone) to determine if they had made changes in any of the four areas. Change was rated by an interviewer who was blind to the results of the scale. The ratings were made on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 to 3. The anchor points for the scale are given in Table 2. Each of the four areas was rated separately on a scale from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more change.

The mean ratings on the Overall Readiness Scale in the four areas were: living, 14; learning, 14.88; working, 14.57; and socializing, 14.78. There were no significant correlations between rehabilitation readiness and number of hospitalizations, age, or length of time at the day treatment program. Positive correlations (Pearson coefficients) were found between rehabilitation readiness scores and outcome in the areas of living (r=.62, p<.001), learning (r=.53, p p<.001), and working (r=.66, p p<.001). In the working domain, anecdotal data lend validity to the correlational results in that subjects with the highest readiness scores actually obtained jobs. Four found full-time paid employment, four found part-time paid employment, and one volunteered part time. Only the correlation between rehabilitation readiness in the social area and social functioning outcome did not reach statistical significance.

Although other studies have examined predictors of occupational functioning for persons with schizophrenia (14), this study was the first to test whether a standardized format for assessing rehabilitation readiness was a valid predictor of rehabilitation outcome. Results of this study suggested that an essential element in determining an individual's potential to make a change in one or more domains of functioning was the degree to which that person expressed a readiness to make a change. Consequently, a formal assessment of rehabilitation readiness using a method such as the rehabilitation readiness assessment and the Overall Readiness Scale should be included in the functional evaluation of seriously mentally ill clients for psychiatric rehabilitation.

Afterword by the column editors:

Mentally disabled individuals who receive treatment in community-based facilities have deficits in more than one area of their lives. Yet clinicians often identify skill deficits and then try to ameliorate them before they have determined the degree of dissatisfaction and motivation to change that a client may have in one or more domains of functioning. One reason for this tendency may be that clinicians use faulty assumptions that are driven by their own values and biases rather than by clients' preferences. A clinician may wrongly assume that a client who is not working prefers to be in competitive employment, or that a client with few friends wants a larger social network. The study by Dr. Ferdinandi and his colleagues suggests that an individual's subjective readiness to change should be considered as part of the rehabilitation assessment.

Although preliminary, these findings suggest that practitioners can profitably use the rehabilitation readiness assessment in determining their clients' readiness to make changes in their lives. By merging the results of the rehabilitation readiness assessment or similar interventions with a client's subjective experiences, service planners may be able to maximize the "hit rate" for linking specific rehabilitation modalities to assessed needs with better biopsychosocial outcomes.

In the current era of fiscal constraint, with its emphasis on cost-effectiveness of service delivery, accurately predicting which intervention is most likely to benefit a client has taken on a new level of urgency. New methods of predicting social and vocational outcomes of psychiatric treatment and rehabilitation may be found in neurocognitive tests (3). How neuropsychological functioning can be informative in psychosocial rehabilitation has been recently demonstrated (15,16).

Although Dr. Ferdinandi and his colleagues provide a compelling rationale for the use of multidimensional treatment planning and evaluation, more comprehensive assessment and treatment planning instruments are required to tailor an effective, individualized rehabilitation program. For example, the Client Assessment of Strengths, Interests, and Goals (CASIG) consists of a battery of instruments designed to help therapists plan, document, and evaluate biopsychosocial rehabilitation (17). The assessment information is collected during a 60- to 90-minute interview with the client, with corroborating information collected from the client's significant others and from treatment personnel who know the client well. The assessment examines functional living skills, subjective quality of life, psychiatric symptoms, compliance with medication, and unacceptable community behaviors. In addition, the client's preferences for changing his or her behavior in each area are elicited.

The fundamental assumption underlying the CASIG is that the plan for services must integrate the goals, needs, and constraints of all the relevant stakeholders—the client, his or her significant others, individuals in the living environment, and the payer or payers. Moreover, the CASIG evaluation system has been designed with the presumption that treatment planning does not end with the collaborative development of the client's service plan. Instead, treatment consists of continuous cycles of assessment, planning, and service delivery. These cycles reflect the ever-changing nature of the client's clinical status; as the client changes, so too does the treatment. In such a fluid environment, treatment cannot be successful unless assessment and services are intertwined partners in an ongoing process.

Dr. Ferdinandi is supervisor of the department of psychiatric rehabilitation, Ms. Yoottanasumpun is rehabilitation therapist, and Dr. Bermanzohn is medical director at the Queens Day Center, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, 87-80 Merrick Boulevard, Jamaica, New York 11423. Dr. Ferdinandi is also adjunct assistant professor in the School of Education and Human Sciences at St. John's University in Jamaica, New York, where Dr. Pollack is professor in the department of computer information systems and decision sciences. Dr. Pollack is also associate director of the biostatistics department at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in Glen Oaks, New York. Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., and Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 39 subjects with schizophrenia who participated in a rehabilitation readiness assessment group

|

Table 2. Anchor point criteria for ratings of participants' six-month change in areas measured by the Overall Readiness Scale

1. Strauss J, Carpenter W: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: characteristics of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 27:739-746, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Strauss J, Carpenter W: Characteristic symptoms and outcome in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 30:429-434, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Green M: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321-330, 1996Google Scholar

4. Anthony WA, Cohen MR, Farkas MD: Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Boston, Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1990Google Scholar

5. Massel HK, Liberman RP, Mintz J, et al: Evaluating the capacity to work of the mentally ill. Psychiatry 53:31-42, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, et al: National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia: prognosis and predictors of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:239-246, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Anthony WA, Rogers ES, Cohen M, et al: Relationship between psychiatric symptomatology, work skills, and future vocational performance. Psychiatric Services 46:353-358, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Gehrs M, Goering P: The relationship between working alliance and rehabilitative outcomes of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 18:43-54, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Bell M, Lysaker PH, Milstein RM: Clinical benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:51-67, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cohen MR, Anthony WA, Farkas MD: Assessing and developing readiness for psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services 48:644-646, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Strauss J: Subjective experiences of schizophrenia: toward a new dynamic-psychiatry II. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:179-187, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Pascaris A: Social recreation: a blind spot in rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15:44-54, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Cohen M, Farkas M, Cohen B: Training Technology: Assessing Readiness for Rehabilitation. Boston, Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1992Google Scholar

14. Beiser M, Bean G, Erickson D, et al: Biological and psychosocial predictors of job performance following a first episode of psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:857-863, 1994Link, Google Scholar

15. Malla AK, Lazosky A, McLean T, et al: Neuropsychological assessment as an aid to psychosocial rehabilitation of severe mental disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:169-173, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Spaulding W, Reed D, Storzbach D, et al: The effects of a remediational approach to cognitive therapy for schizophrenia, in Outcome and Innovation in Psychological Treatment of Schizophrenia. Edited by Wykes T. London, Wiley, 1998Google Scholar

17. Kopelowicz A, Corrigan P, Wallace C, et al: Biopsychosocial rehabilitation, in Psychiatry. Edited by Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA. Philadelphia, Saunders, 1996, pp 1513-1534Google Scholar