Cost-Effectiveness of Clozapine Therapy for Severe Psychosis

Abstract

The cost-effectiveness of using the atypical antipsychotic medication clozapine for severe psychosis was examined in a rural public-sector community mental health setting in Virginia. Based on a sample of 20 patients, use of clozapine resulted in estimated cost savings of between $3,000 and $9,000 per patient per year, including the costs of dropouts from treatment. Savings were mainly due to a decline in hospitalization from 47.7±59.8 days per patient in the year before clozapine treatment to 4.6±11.3 days in the year after. Although this study had methodological limitations, the results suggest that clozapine may be cost-effective in this setting.

Although atypical antipsychotic agents like clozapine are considered to be more efficacious than typical antipsychotic agents, these drugs cost more than conventional medications. However, of the seven studies of the cost-effectiveness of clozapine, five found that increased drug costs were more than offset by decreased overall treatment costs, particularly due to reduced hospitalization rates (1,2,3,4,5). One found no overall change (6), and another an increase in cost (7).

Only two of the seven studies included cost analyses of dropouts from treatment (3,6). Only two studies were conducted solely in the public sector—one in a state hospital (1) and another in a veterans hospital (6). Only one study was randomized and double-blind, and it found no change in overall costs with clozapine treatment of refractory schizophrenia (6).

The study reported here is the only one that combines several aspects of treatment—use of clozapine, public-sector financing, community-based treatment, a rural setting, and the inclusion of dropouts from clozapine treatment in the cost estimates. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that use of clozapine would offset increased drug costs by reducing psychiatric hospitalization costs in this treatment setting.

Methods

In this retrospective study, records of all 45 patients in a clozapine treatment program from 1992 to 1996 in the Northwestern Community Services Board in Winchester, Virginia, a rural community, were examined. Most patients began treatment with clozapine as inpatients in a state hospital.

Before that phase of data collection, we decided to analyze all available data on all patients treated with clozapine in our setting, including those who continued on clozapine for more than 12 months and those who began on clozapine but either did not respond or stopped in less than 12 months due to side effects. We also made an a priori decision to exclude patients who appeared to be responding to or tolerating clozapine but simply had not yet taken it for 12 months, because we wanted to compare treatment cost estimates one year before and one year after patients started clozapine treatment.

The 20 subjects in the study were the patients who continued treatment for at least 12 months (mean±SD= 42.4±13.3 months; range, 17 to 44 months). Of the 25 patients not studied, ten received clozapine for less than 12 months (mean±SD=6.1±3 months; range, two to six and a half months), four left the region before data collection was complete, and 11 discontinued clozapine before one year. One discontinued because of leukopenia, four for noncompliance, one because of pregnancy, one because the drug lacked efficacy, and four because of other side effects. The patient with leukopenia, who had a white blood cell count of 2,300, was not hospitalized and recovered without permanent medical sequelae when clozapine was discontinued. No statistically significant demographic or clinical differences were found between those who received clozapine for more than 12 months and those who dropped out of treatment.

In the final sample of 20 patients, diagnoses based on DSM-IV criteria were schizophrenia for 14 patients, schizoaffective disorder for five, and bipolar disorder with psychotic features for one. The sample consisted of 14 men and six women, with a mean±SD age of 39.4±7.9 years. Specific information about the patients' previous treatment and past course of illness was unavailable at the time of data collection, mainly due to limitations in the accuracy and extent of such history as recorded in the available medical records.

Costs were estimated for hospital days, physician and nursing services, case management, psychosocial treatment, emergency services, and outpatient family therapy. Statistical analyses consisted of paired t tests and chi square tests.

Results

For the 20 patients, hospitalization time decreased from a mean±SD of 47.7±59.8 days per patient per year before clozapine treatment to 4.6± 11.3 days after clozapine treatment (t=3.17, df=38, p=.003). Only four patients (20 percent) were hospitalized in the year after starting clozapine, compared with 16 (80 percent) in the year before (χ2=12.1, df=1, p<.001).

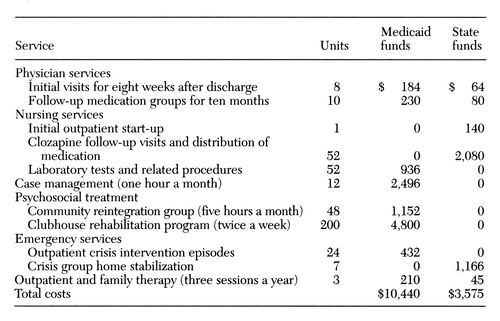

Table 1 describes the cost calculations for one patient based on all available information. We estimated the overall cost at $14,015 per patient per year, which was reimbursed mostly by federal Medicaid funds in the amount of $10,440 per patient per year and partly by state funds of $3,575 per patient per year. With average public hospital costs of approximately $500 a day in this region, reductions in hospitalization resulted in a net savings of $9,635 per patient per year, which was calculated by subtracting the overall cost of $14,015 per patient per year for the estimated savings of $23,650 per patient per year in hospital costs. The cost per patient for those who dropped out of clozapine treatment was estimated at $9,315. If the 11 dropouts in this sample are added to the 20 patients who continued clozapine, the net estimated savings was $2,911 per patient per year.

Discussion and conclusions

Among 20 patients with psychotic disorders treated in the public sector in a rural setting in Virginia, use of clozapine resulted in a marked decrease in the number of days patients were hospitalized in the following year. Despite significant direct costs for the drug and for clinical care, the marked decrease in psychiatric hospitalization resulted in estimated cost savings of between $3,000 and $9,000 per patient per year, even when the costs of 11 patients who dropped out of treatment were included.

The overall cost savings are less than those observed in some previous studies (1,2), but the results still represent a cost savings. The decline in hospitalization in this study was found in previous reports (1,6,8). The findings of this study also agree with those of previous studies in urban public settings (1,6) and private settings (3,4). Thus cost savings from clozapine use appear to be realized in various demographic and clinical conditions. Our results also agree with those of other studies that included cost analyses for dropouts (3,6) and with another study in which we reanalyzed cost savings, including dropout expenses, and found a savings of $3,750 per patient per year (5).

Caution is warranted in generalizing results from studies of populations with high hospitalization rates, which was the case in this study and in other studies of patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, to the entire population of patients with schizophrenia or mood disorders, many of whom are not repeatedly hospitalized (9).

Difficulties in obtaining funds for atypical antipsychotic agents are not uncommon. However, it would seem to be cost-effective to adequately fund these powerful treatments rather than to "save" money with cheaper older-generation antipsychotic medications, which ultimately cost more, not only in continued illness and unnecessary suffering but also financially.

The major limitation of this study was the use of a mirror design. Because factors other than clozapine treatment could not be controlled with this design, the ability to interpret the results as being due to clozapine is limited. Other factors might include increased compliance due to the weekly clinic visits associated with clozapine management. No data were collected about other aspects of treatment costs, including costs of medical care or medical hospitalizations or change in the number of outpatient visits.

All cost figures were estimates of costs and not actual observed costs, because data on actual costs were not collected systematically. In addition, the study was retrospective. No comparison group of patients treated with typical neuroleptics was used to rule out the possibility that the decrease in costs in the year after clozapine initiation was due to nonpharmacologic factors. Although this study did not have such a control group, a previous study that made cost estimates using such a group supported continued cost-effectiveness of clozapine over typical neuroleptic agents; the cost savings was about $3,000 per patient per year, including dropouts (10).

A further limitation was exclusion from the study of 25 of 45 patients treated with clozapine. Based on currently available data, of the ten patients who were excluded from the study because they had not yet taken clozapine for a year, only one was rehospitalized during the follow-up period (6.1±3 months). Definitive outcome data were not available for the four patients excluded from the study because they left the region; however, their continued clozapine treatment (mean±SD=42.4±13.3 months) suggests some efficacy, thus making it unlikely that their inclusion in the sample would have changed the direction of the results.

Given the limitations described, this study suggests that clozapine may be cost-effective in a rural, public-sector, community-based setting.

Dr. Ghaemi is senior investigator in and Dr. Goodwin is director of the Center on Neuroscience, Medical Progress, and Society of George Washington University. Dr. Ghaemi is also research assistant professor of psychiatry and Dr. Goodwin is professor of psychiatry in the department of psychiatry at George Washington University, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Eighth Floor, Washington, D.C. 20037. Mr. Ziegler is executive director and Mr. Peachey is deputy director of the Northwestern Community Services Board in Winchester, Virginia.

|

Table 1. Cost estimates for first year of clozapine treatment of one patient in the Northwestern Community Services Board of Winchester, Virginia

1. Reid WH, Mason M, Toprac M: Savings in hospital bed-days related to treatment with clozapine. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:261-264, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Honigfeld G, Patin J: A two-year clinical and economic follow-up of patients on clozapine. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:882-885, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Meltzer HY, Cola P, Way L: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1630-1638, 1993Link, Google Scholar

4. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC, Cole JO: Hospitalization rates among clozapine-treated patients: a prospective cost-benefit analysis. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 4:247-250, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Revicki DA, Luce BR, Weschler JM, et al: Clozapine's cost benefits (ltr). Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:93-94, 1990Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, et al: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 337:809-815, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Jonsson D, Walinder J: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine treatment in therapy-refractory schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 92:199-201, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Meltzer HY, Cola PA: The pharmacoeconomics of clozapine: a review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55(Sept suppl B):161-165, 1994Google Scholar

9. Rosenheck R, Charney DS, Frisman LK, et al: Clozapine's cost-effectiveness (ltr). American Journal of Psychiatry 152:152-153, 1995Link, Google Scholar

10. Revicki DA, Luce BR, Weschler JM, et al: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:850-854, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar