Brief Reports : HIV-Related Risk Behaviors Among Psychiatric Inpatients in India

Abstract

The study explored patterns of risk behavior and knowledge about HIV and AIDS among patients in an inpatient psychiatric facility in south India. Fifty-nine consecutive patients admitted to a state psychiatric hospital were interviewed using a semistructured questionnaire. Fifty-one percent had a history of recent risk behavior, and 86 percent had inadequate knowledge about AIDS. The most common high-risk behavior was unprotected heterosexual intercourse with a high-risk partner. There was no correlation between knowledge and high-risk behavior. The findings underscore the need to specifically tailor intervention programs.

Increasing evidence suggests that psychiatrically ill patients are at high risk for HIV infection (1). Studies of patients in Western settings have shown that increased risk is often related to sexual or drug-related behavior (2,3) and that such behavior is usually associated with lack of adequate information about AIDS. However, Volavka and associates (4) cautioned against generalization of these findings to other geographical areas and emphasized the importance of studying patterns of risk in different settings and cultures.

This caution is supported by a study of psychiatric patients in Taiwan (5), which found the seroprevalence of HIV infection in this group to be zero. Although the reasons for this finding were not studied, it was attributed to social and cultural characteristics of the Chinese and to the absence of comorbid drug abuse in those patients. In a recent study, a 3.4 percent HIV seroprevalence was found among psychiatric patients with high-risk behavior at our inpatient facility in India (6). The most common high-risk behavior among the general population in India is unprotected heterosexual intercourse (7).

For intervention programs to be effective, they must be tailored toward addressing the specific high-risk behaviors found among patients (8). The exploratory pilot study reported here assessed the patterns of high-risk behavior and knowledge of HIV and AIDS among psychiatric patients at our inpatient facility in India.

Methods

The study was conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences in Bangalore, a large teaching state hospital with a 600-bed inpatient facility. Patients with a wide range of psychiatric diagnoses are admitted to separate wards based on severity of illness and treatment required. Between July and October 1996 consecutively admitted patients with a primary diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder were approached for informed consent to participate in the study. Patients with a comorbid alcohol or drug use disorder were included, but those admitted only for the treatment of substance abuse or dependence were not recruited.

Thirty male and 30 female patients were selected for the study. However, one male patient who had been admitted primarily with sexual dysfunction and disturbed sexual orientation was later excluded from the analysis. The mean±SD age of the male patients was 28.3±8.7 years and that of the female patients was 31.6±11.3 years. All patients were Indians.

The patients were interviewed using a semistructured questionnaire that was designed at the hospital after a review of literature. The questionnaire was used previously with patients with substance use disorder and with health care personnel. The questionnaire has two parts. The first part consists of 51 forced-choice questions covering five broad areas of knowledge about HIV infection. Possible scores on this part of the questionnaire range from 0 to 51, with higher scores indicating more knowledge. Two questions in each section were designated key questions.

The second part of the questionnaire includes 19 items covering details of high-risk activities over the past two years, including high-risk sexual activity, sharing needles while using intravenous (IV) drugs, and exposure to inadequately screened blood products through transfusion. High-risk sexual behavior includes a history of unprotected homosexual and heterosexual sex with multiple partners or someone who has multiple partners; unprotected sex with someone at high risk, for example, persons who share needles for IV drugs; and unprotected sex in exchange for money or drugs.

After assuring patients of the confidentiality of their answers, interviewers met with patients face-to-face to complete the questionnaire. Male patients were interviewed by a male investigator (MPC) and female patients by a female investigator (SSVE). After the interview, the patients were given pretest counseling and offered an HIV ELISA blood test.

Based on answers to the first part of the questionnaire, patients were divided into two groups. Patients who answered all the key questions correctly and had a total score of 25 or more were designated as having adequate knowledge about HIV and AIDS. Patients who did not meet those criteria were designated as having inadequate knowledge.

The high-risk behavior of patients grouped by sex, diagnosis, and level of knowledge was compared using the chi square test and Fisher's exact probability test.

Results

Thirty-one patients (52 percent) had not received any formal education, eight patients (14 percent) had completed primary school, 12 (20 percent) had completed secondary school, and eight (14 percent) had received some college education. Twenty-seven patients (46 percent) were married.

Clinical diagnoses were schizophrenia and nonaffective psychosis for 22 patients (37 percent), affective disorders for 31 patients (53 percent), obsessive-compulsive disorder for two patients (3 percent), and personality disorders for four patients (7 percent).

Male and female patients did not differ in sociodemographic features or diagnosis. However, only ten female patients (33 percent) had any formal education, compared with 18 male patients (62 percent), although this difference was not significant.

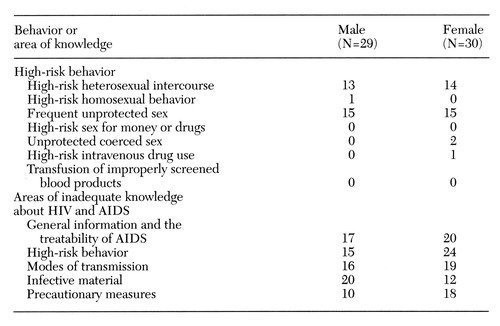

The types of high-risk behavior patients engaged in over the past two years and their areas of inadequate knowledge about HIV and AIDS are shown in Table 1. Thirty patients (51 percent), including 15 male patients and 15 female patients, had a history of HIV-related high-risk behavior. For five of the female patients, the risk was due to their having sex with a spouse or partner who had multiple sexual contacts.

Thirteen patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (59 percent of the patients with that diagnosis), 15 patients with affective disorder (48 percent), and two patients with personality disorder (50 percent) had a history of high-risk behavior. Forty-one patients—19 male patients and 22 female patients—had been sexually active in the last two years. Of those patients, only two female patients reported that their partners consistently used condoms during intercourse.

Fifty-one patients (86 percent)—27 male patients and 24 female patients—had inadequate knowledge about AIDS. More than 60 percent of the patients had inadequate knowledge about general information, treatment, and high-risk behaviors related to HIV infection. Of the eight patients with adequate knowledge about AIDS, five patients were found to have a history of high-risk behavior. Further, no significant difference in the prevalence of high-risk behavior was found between the group with adequate knowledge and the group with inadequate knowledge.

None of the 55 patients who consented for ELISA testing were found to be HIV seropositive.

Discussion and conclusions

Although the prevalance of risk behavior among the patients in the study was high (51 percent) and is similar to other rates of risk behavior reported in the literature (2,3,4), there are some important differences. Sharing of needles for IV drug use (N=1), high-risk homosexual intercourse (N=1), and unprotected coerced sex (N=2) were not as significant a problem as reported in studies conducted in the U.S. (2,3). None of the patients had a history of casual sexual encounters or exchange of sex for shelter or money. The most common high-risk behavior among male patients was unprotected heterosexual intercourse with a commercial sex worker. Among female patients, the most common high-risk behavior was the inability to ensure the use of a barrier during intercourse despite a knowledge of their partner's high-risk behavior. However, this pattern of risk behavior may not be unique to our setting, as similar patterns have been reported in studies from American centers (9).

Studies have also demonstrated the inability of psychiatric patients to use their knowledge about HIV to alter their risk-taking behavior (2,3). The absence of any difference in high-risk behavior despite knowledge in the current study upholds this finding. A possible explanation of the differences in AIDS-related knowledge between the sexes could be the higher number of educated male patients in the sample. The female patients' inability to insist on safe sex is probably related to cultural factors such as powerlessness and poor negotiation skills. Our study helped to point out areas of inadequate knowledge, which were subsequently used to focus the intervention models we are currently developing.

The zero seroprevalence in the group is explicable on the basis of the low seroprevalence in the general population at the time of the study. However, the study should be replicated using a larger sample, including more patients with a diagnosis of personality disorder, who have been found to have a higher incidence of high-risk behavior at our center (6).

Dr. Chopra is a resident, Dr. Eranti is senior resident, and Dr. Chandra is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Hosur Road, Bangalore 560 029, India. Address correspondence to Dr. Chandra (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Frequency of high-risk behavior and areas of inadequate knowledge about HIV and AIDS among 59 psychiatric inpatients in Bangalore, India

1. Stefan MD, Catalan J: Psychiatric patients and HIV infection: a new population at risk? British Journal of Psychiatry 167:721-727, 1995Google Scholar

2. Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Bahr GR, et al: AIDS/HIV risk behavior among the chronic mentally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:886-889, 1992Link, Google Scholar

3. Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Johnson JR, et al: Factors associated with risk for HIV infection among chronically mentally ill adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:221-227, 1994Link, Google Scholar

4. Volavka J, Convit A, O'Donnell J, et al: Assessment of risk behaviors for HIV infection among psychiatric inpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:482-485, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Chen CH: Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection among Chinese psychiatric patients in Taiwan. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:441-442, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Chandra PS, Ravi V, Puttaram S, et al: HIV and mental illness (ltr). British Journal of Psychiatry 168:654, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. HIV/AIDS in India: National Scenario. New Delhi, National AIDS Control Organization, 1994Google Scholar

8. Meyer I, Cournos F, Empfield M, et al: HIV prevention among psychiatric inpatients: a pilot risk reduction study. Psychiatric Quarterly 63:187-197, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Cournos F, Mc Kinnon K, Meyer-Bahlburg M, et al: HIV risk activity among persons with severe mental illness: preliminary findings. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:1104-1106, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar