Treatment of Inhalant-Induced Psychotic Disorder With Carbamazepine Versus Haloperidol

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The efficacy and adverse effects of carbamazepine and haloperidol were compared in the treatment of inhalant-induced psychotic disorder. METHODS: Forty male patients admitted to an acute psychiatric unit for treatment of inhalant dependence and inhalant-induced organic mental disorder, as diagnosed by DSM-III-R,were randomly assigned to receive five weeks of treatment with carbamazepine or haloperidol in identical-appearing capsules. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the DiMascio Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale were administered weekly. RESULTS: Both treatment groups improved significantly over time. A reduction of symptom severity of 48.3 percent in the carbamazepine group and 52.7 percent in the haloperidol group was observed. Approximately half the patients in each group were considered treatment responders at the end of the study. Adverse effects were significantly more common and more severe in the haloperidol group. CONCLUSIONS: Carbamazepine appears to have comparable efficacy but fewer adverse effects than haloperidol for the treatment of inhalant-induced psychotic disorder.

Chronic inhalation of solvents, including glue, paint thinners, and gasoline, can produce a persistent psychotic disorder characterized by delusions and hallucinations (1). The presence of toluene appears to play an important role in the genesis of inhalant-induced psychotic symptoms (1,2,3,4). This effect is probably mediated by the increase of free intraneuronal calcium levels (5) and by the enhancement of dopamine release from presynaptic terminals (6)

In Mexico inhalant-induced psychotic disorder is a common diagnosis in public psychiatric hospitals, and although its precise incidence and prevalence are unknown, inhalants are among the three drugs most widely consumed by the Mexican urban population (7). In the United States about 17 percent of adolescents have sniffed inhalants at least once in their lives, and among children under 18, the level of inhalant use is comparable to that of stimulant use (8). Despite the widespread use of inhalants, the psychiatric complications of chronic inhalant abuse have received limited research attention (1,2,3,4,9).

Treatment of inhalant-induced psychotic disorder has primarily involved the use of antipsychotics, often for extended periods (1). However, the frequent development of extrapyramidal side effects and of tardive dyskinesia has complicated this treatment approach, with poor compliance and early discontinuation of therapy common problems. Insofar as brain damage appears to be common among patients with inhalant-induced psychotic disorder (10), they may be at particular risk for the adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment (11,12). Consequently, a need exists for alternate pharmacological approaches to the management of this disorder.

The anticonvulsant carbamazepine represents one possible alternative to antipsychotics for the treatment of inhalant-induced psychotic disorder. Carbamazepine has been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of bipolar disorder (13,14,15). Several reports have also shown it to be useful as an adjunct to antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, reducing the dose of the antipsychotic needed to treat these disorders (16,17,18). The efficacy of carbamazepine in the treatment of psychotic symptoms may be explained by its ability to reduce neuronal hyperexcitability and dopaminergic tone. This effect is probably mediated by the calcium-antagonistic properties of carbamazepine (19).

The study reported here was done to compare the efficacy of carbamazepine with that of haloperidol among patients with persistent delusional and hallucinatory symptoms induced by chronic inhalant dependence.

Methods

Subjects

Forty male patients admitted to an acute psychiatric unit at the Fray Bernardino Alvarez Psychiatric Hospital in Mexico City between December 1989 and January 1992 participated in the study. All patients met DSM-III-R criteria for inhalant dependence and inhalant-induced organic mental syndrome (20). Diagnoses were made by a psychiatrist using a symptom checklist developed to evaluate patients for study participation. All patients gave informed consent to participate, and the study was approved by the institutional review board.

Patients were excluded from participation if they had a history of a major medical disorder, schizophrenia, or another substance use disorder or if they had used a psychotropic drug during the week before study enrollment.

Study patients had a mean±SD age of 24.9±4.5 years and reported a mean duration of inhalant abuse of 119.6±81.3 months. Their mean±SD baseline score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (21,22) was 25.2±7. No significant differences between patients who were assigned to the carbamazepine group and patients assigned to the haloperidol group were found on these measures.

Assessments

Baseline assessments with the BPRS and the DiMascio Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale (DMEPS) (23,24) were conducted before initiation of treatment and then weekly for five weeks. Scores on the DMEPS can range from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Blood samples were drawn at baseline and then weekly for determination of CBC, hepatic enzymes, and carbamazepine plasma levels.

Treatment

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either carbamazepine or haloperidol. The medication was administered under double-blind conditions using identical-appearing capsules containing either 200 mg of carbamazepine or 5 mg of haloperidol. Initially, patients received one capsule three times a day. For patients who failed to show a 25 percent decrease in BPRS score from baseline, the dosage was increased at weekly intervals by one capsule per day to a maximum of eight capsules per day.

For management of severe agitation, 5 mg of a short-acting form of haloperidol was administered intramuscularly as needed to patients in both treatment groups. Patients requiring more than two doses of haloperidol intramuscularly per week were considered treatment failures, and their study participation was discontinued. Four mg of the anticholinergic agent biperiden was administered twice a day if the patient's DMEPS score exceeded 2, based on weekly assessments by an independent clinician.

Data analysis

Treatment groups were compared at baseline using the t test for independent samples to examine continuous measures and Fisher's exact test for categorical measures. Outcome was analyzed by intention to treat, using the last observation carried forward. To compare clinical outcomes, analysis of variance for repeated measures was used, with time as a within-subject factor and medication group as a between-group factor. The significance level was set at .05. The mean difference between groups for the reduction in symptoms from baseline to treatment endpoint was calculated, as were 95 percent confidence intervals (25). Clinical response was defined as a reduction in BPRS score by a minimum of 50 percent at the end of the study.

Results

Thirty-one patients completed five weeks of treatment. Nine patients terminated treatment prematurely, five in the carbamazepine group and four in the haloperidol group. The most common reason for premature termination was psychomotor agitation, which occurred with three patients in the carbamazepine group and two in the haloperidol group. One patient on carbamazepine discontinued treatment due to a skin rash, and another was withdrawn due to elevated liver enzymes. One patient on haloperidol was withdrawn from treatment due to anticholinergic delirium after the administration of biperiden, and another was withdrawn due to severe extrapyramidal side effects. The mean±SD number of treatment weeks was 4.5±1 for carbamazepine patients and 4.4±1.1 for haloperidol patients. The treatment groups did not differ significantly with respect to the proportion of patients who completed the study or the mean duration of study participation.

The mean±SD daily dose of haloperidol at the end of the study was 21.7±10.6 mg. The mean daily dose of carbamazepine was 920±336.5 mg, which yielded a serum carbamazepine level of 10.8±3.1 μg/L. Only three haloperidol patients (15 percent) and two carbamazepine patients (10 percent) had to take the maximum allowed dose of eight capsules per day. Although carbamazepine patients were somewhat more likely than haloperidol patients to receive haloperidol intramuscularly to control agitation (45 percent versus 20 percent), the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=.09). The total dose of haloperidol given to control agitation did not differ significantly between groups (9.4±1.6 mg for carbamazepine patients and 7.5± 2.8 mg for haloperidol patients).

However, extrapyramidal symptoms were rated as significantly worse in the haloperidol group. At the end of treatment, the DMEPS score was 4.3±2.9 for the haloperidol group, compared with .7±1.1 for the carbamazepine group (t=-7.19, df=38, p<.001). Biperiden was administered to 16 haloperidol patients (80 percent) at a mean daily dose of 4.6±2 mg. No carbamazepine patients required treatment with biperiden. The difference in the proportion of subjects receiving biperiden between groups was significant (Fischer's exact test, p<.001).

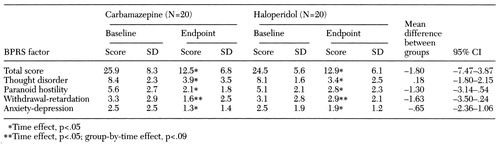

No main effect of medication group on BPRS scores was found. However, as shown in Table 1, a significant reduction in BPRS scores as a function of time was noted (F=79.13, df=1,38, p<.001). A 48.3 percent reduction in symptom severity was found in the carbamazepine group and a 52.7 percent reduction in the haloperidol group. Moreover, approximately half of the patients in both groups were considered responders (45 percent of the carbamazepine group and 50 percent of the haloperidol group). The interaction of medication group by time was also not significant. The mean difference between groups in the decline in BPRS scores was 1.80.

Further analysis showed no main effects of medication group or the group-by-time interaction, although a significant main effect of time on several BPRS factors was noted. They included thought disorder (F=89.10, df=1,38, p<.001), paranoid hostility (F=40.90, df=1,38, p<. 001), and anxiety-depression (F=4.31, df=1,38, p=.05).

As with the other BPRS factors, no main effect of medication group on the withdrawal-retardation factor was found. However, a significant effect of time on this factor was noted (F= 3.91, df=1,38, p=.05), as well as a nonsignificant trend for the group-by-time interaction (F=3.10, df=1,38, p=.09). The trend reflects less improvement on the withdrawal-retardation score among patients on haloperidol compared with those receiving carbamazepine, a finding consistent with the higher prevalence and greater severity of extrapyramidal symptoms among patients in the haloperidol group.

Discussion and conclusions

This study showed that beginning in the first week of treatment and continuing through the five-week treatment period, patients in the carbamazepine group exhibited an antipsychotic response comparable to that in the haloperidol group, but with fewer extrapyramidal symptoms. Although the treatment groups were similar in the number of treatment weeks completed, number of patients who terminated prematurely, and rate of reduction of psychotic symptoms, more carbamazepine patients required adjunctive haloperidol to control psychomotor agitation. However, the total dose of haloperidol required to control agitation did not differ between treatment groups.

Nevertheless, administration of adjunctive haloperidol to agitated patients on carbamazepine may have introduced a confounding effect. An attempt was made to minimize this problem by limiting the dose of adjunctive haloperidol to 10 mg a week and by discontinuing participation of patients who required a larger dose. It is unclear if administration of a higher dose of carbamazepine than was used in this study might provide better symptom control, because most of the additional haloperidol was administered during the first two weeks of the study when the dosage of carbamazepine was lowest. In addition, the substantial extrapyramidal symptoms resulting from treatment with haloperidol may have interfered with the blind study design, although an attempt was made to limit this effect by having an independent clinician evaluate and treat extrapyramidal symptoms before assessment with the BPRS.

A search of the literature revealed no other controlled treatment trials among patients with a persistent drug-induced psychotic disorder. Patients in this study had a history of persistent psychotic symptoms, as reflected by previous psychiatric hospital admissions, and in most cases an established temporal association between a history of severe inhalant abuse and development of psychotic symptoms. In general, these subjects began to experience the psychotic disorder after several months or years of inhalant dependence, and it was accompanied by cognitive impairment and in several cases other complications of inhalant abuse, including polyneuropathy.

The findings suggest that carbamazepine can be used as a first-line treatment for inhalant-induced psychotic disorder, particularly for patients without high levels of psychomotor agitation. For patients with more severe behavioral disturbances, carbamazepine may be used initially, with intermittent use of an antipsychotic to control agitation. Although it remains to be demonstrated that such an approach would enhance efficacy, the results of this study indicate that it would likely reduce adverse effects. Efforts to replicate these findings should include a placebo control, with appropriate provisions for early termination in the absence of adequate improvement.

The mean reduction in symptoms during treatment generally favored carbamazepine, although these differences were not statistically significant. A larger sample of patients is needed to increase the likelihood of identifying medication differences that this study may have failed to show due to inadequate statistical power, which is evidenced by the width of the 95 percent confidence intervals. Finally, a comparison of low-dose and high-dose treatment with carbamazepine would help to determine the optimal dosing strategy in the treatment of inhalant-induced psychotic disorder.

Dr. Hernandez-Avila and Dr. Ortega-Soto are affiliated with the division of clinical research at the Mexican Institute of Psychiatry in Huipulco Tlalpan, Mexico City. Dr. Hernandez-Avila and Dr. Kranzler are with the department of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut Health Center (MC2103), Farmington, Connecticut 06030 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Jasso is with the Fray Bernardino Alvarez Psychiatric Hospital in Mexico City. Ms. Hasfura-Buenaga is with the department of mental health of the Mexico Health Ministry in Mexico City.

|

Table 1. Scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) of inpatients with inhalant-induced psychotic disorder treated with carbamazepine or haloperidol

1. Byrne A, Kirby B, Zibin T, et al: Psychiatric and neurological effects of chronic inhalant abuse. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 36:735-738, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Goldbloom D, Chouinard G: Schizophreniform psychosis associated with chronic industrial toluene exposure: case report. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 46:350-351, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

3. Fornazzari L, Wilkinson D, Kapur B: Cerebellar, cortical, and functional impairment in toluene abusers. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 67:319-329, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lewis J, Mortiz D, Mellis L: Long-term toluene abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:368-370, 1981Link, Google Scholar

5. Liu Y, Fechter LD: Toluene disrupts outer hair cell morphometry and intracellular calcium homeostasis in cochlear cells of guinea pigs. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 142:270-277, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Lam HR, Ladefoged O, Ostergaard G, et al: Four weeks of inhalation exposure of rats to p-cymene affects regional and synaptosomal neurochemistry. Pharmacology and Toxicology 79:225-230, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Medina NM, Tapia R, Sepulveda J: Encuesta nacional de adicciones [national survey of addictions]. Salud Mental 12:7-12, 1989Google Scholar

8. Beauvais F: Volatile solvents abuse: trends and patterns, in Inhalant Abuse: A Volatile Research Agenda. Edited by Sharp CW, Beauvais F, Spence, R. NIDA Research Monograph 129. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1993Google Scholar

9. Simpson DD: A longitudinal study of inhalant use: implications for treatment and prevention, ibidGoogle Scholar

10. Dinwiddie S: Abuse of inhalants: a review. Addiction 89:925-939, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Pourcher E, Baruch P, Bouchard RH, et al: Neuroleptic-associated tardive dyskinesias in young people with psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:768-772, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Jankovic J: Tardive syndromes and other drug-induced movement disorders. Clinical Neuropharmacology 18:197-214, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Post RM, Udhe TW, Roy-Byrne PP, et al: Correlates of antimanic response to carbamazepine. Psychiatry Research 21:71-83, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Small J, Mapper M, Milstein V, et al: Carbamazepine compared with lithium in the treatment of mania. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:915-921, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ortega-Soto HA, Hernandez-Avila CA, Jasso A, et al: La carbamazepina vs el haloperidol en el control del episodio maniaco agudo: resultados de un ensayo clinico controlado [Carbamazepine vs haloperidol in treatment of the acute manic episode: a controlled clinical trial]. Salud Mental 16:44-50, 1993Google Scholar

16. Klein E, Bentale L, Lerrer B: Carbamazepine and haloperidol vs placebo and haloperidol in excited psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:165-170, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lenzi A, Lanzzerini F, Grossi E: Use of carbamazepine in acute psychosis: a controlled study. Journal of International Medical Research 14:78-84, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, et al: A double blind study of adjunctive carbamazepine versus placebo on excited states of schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 80:250-259, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Walden J, Grunze H, Mayer A, et al: Calcium-antagonistic effects of carbamazepine in epilepsies and affective psychosis. Neuropsychobiology 27:171-175, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

21. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Dingermans PM, Frohn de Winter ML, Blecker JAC, et al: A cross-cultural study of the reliability and factorial dimensions of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Psychopharmacology 80:190-196, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. DiMascio A, Bernardo DL, Greenbalt DJ, et al: A controlled trial of amantadine in drug-induced extrapyramidal disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:599-602, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Ortega-Soto HA, Jasso A, Hernandez-Avila CA: La validez y la reproductibilidad de dos escalas para evaluar los sintomas extrapiramidales inducidos por neurolepticos [Validity and reliability of two scales for the assessment of neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms]. Salud Mental 14:1-5, 1991Google Scholar

25. Borenstein M: The case for confidence intervals in controlled clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 15:411-428, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar