Assessing the Quality of Psychiatric Hospital Care: A German Approach

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The German Ministry of Health commissioned a nonprofit organization to develop a tool for assessing the quality of psychiatric hospital care. METHODS: The authors were members of an expert group established to develop an assessment tool that could be used by professional caregivers, patients, patients' relatives, managers, purchasers, and mental health care planners. RESULTS: A three-dimensional model was developed in which 23 quality standards may be applied to 28 areas of practice. For each application, questions can be asked at four levels to stimulate ongoing quality management: the individual treatment process, the individual outcome, the treatment unit, and the hospital as a whole. The authors provide sample questions to illustrate the approach. CONCLUSIONS: The approach to quality assessment embodied in the model is comprehensive and addresses ethical issues, but it is also complicated and difficult to handle. Unlike models developed in the United States, it is not intended to be objective or standardized, and it does not yield a score. To some extent, the model's approach to assessment may reflect German cultural values and traditions.

In the past two decades, political reforms have led to significant changes in psychiatric inpatient care in Germany. Although no psychiatric hospitals have been closed and the overall number of psychiatric hospital beds has not dramatically decreased, huge mental hospitals have been downsized, and psychiatric departments have been established in general hospitals. The general standard of hospital buildings and the staff-patient ratio have both been substantially improved. A special federal directive on staffing for psychiatric hospitals led to a 20 percent increase in therapeutic staff between 1991 and 1995.

Assuming that the increase of staff should result in an improvement of quality of care, the German Ministry of Health funded a project to help promote quality of care and commissioned an independent nonprofit agency, Aktion Psychisch Kranke, with the vaguely defined task of developing a tool for assessing the quality of psychiatric hospital care procedures (1). The nonprofit agency was jointly founded in 1971 by mental health professionals and politicians of all parties within the federal parliament to initiate and support reforms in mental health care in Germany.

Assessment of the quality of psychiatric care is currently a challenge in the United States and other Western countries (2,3,4). Definitions of quality in each country may be based on cultural values and national traditions. An international discussion should consider national peculiarities and priorities. This paper, which presents a German approach to quality assessment of psychiatric care, is intended to contribute to such an international discussion.

Methods

Aktion Psychisch Kranke formed an expert group that worked from 1994 to 1996. The 34 members were psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, and managers from state mental hospitals, psychiatric departments in general hospitals, and health administrations, as well as patients and their relatives. This comprehensive composition of the group was intended to integrate the views of providers, purchasers, and users of hospital care. The authors were members of the group, which was headed by the first author.

The group decided to develop guidelines for the assessment of quality that could stimulate ongoing quality management and be used by anyone involved with hospital treatment, such as hospital staff and organizations of patients' relatives or purchasers of care. The group assumed that quality assessment examines whether a given hospital care process meets quality standards. These standards must be defined and specified. The definition should not exclusively focus on medical treatment goals but should also consider social integration of patients, social values, and norms. Whether the fulfilment of a standard can be measured or operationalized was not considered to be the primary criterion for the assessment of quality.

Results

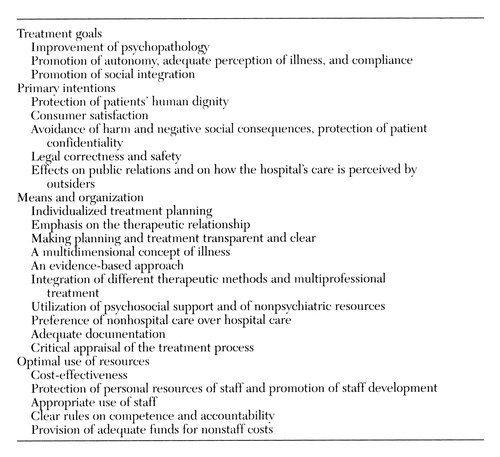

The group defined 23 quality standards in four categories: treatment goals, primary intentions, means and organization, and optimal use of resources. The standards are listed in Table 1.

The group also outlined 28 areas of practice of inpatient care to which the standards may be applied. These areas of practice are admission procedures; diagnostic procedures; drug therapy and other physical treatments; nonspecific and specific psychotherapy; occupational therapy and work therapy; support for living accommodations and self-care; support for work, occupation, and education; support for social contacts and leisure; interaction with relatives; meeting of basic material needs; discharge procedures; handling of compulsory treatment; general medical care and liaison service; therapeutic relationships; treatment and care planning; time management; the therapeutic milieu; operational ward policy; teamwork in treatment; the information and communication system; the documentation system; organization and administration on the ward; management of staff; the hospital's management structure; cooperation between management and clinical staff; public relations; advocacy of patients' interests; and accessibility.

In theory, each quality standard may be applied to each area of practice, so that each aspect of quality may be assessed in any given area. This two-dimensional model was then extended by a third dimension. For any application of a standard in an area of practice, questions may be asked on the level of the individual patient, the treatment unit (usually a ward), and the whole institution or hospital. For the patient, a distinction is made between the treatment process and outcome.

Thus a three-dimensional approach to quality assessment that would permit assessment of almost any aspect of inpatient care was created. The approach is described in a manual developed by the expert group (5).

For most intersections in this model, sample questions have been formulated. For other intersections, such questions appear artificial or may not make sense at all. Questions are intended to stimulate users of the manual to formulate further questions in the areas under consideration. For example, applying the quality standard of promotion of social integration to the area of discharge procedures, a question concerning the treatment process of an individual patient would be "Has the social integration of the patient been sufficiently analyzed and considered in preparation for discharge?" For outcome of an individual patient's treatment, a question would be "Is social integration (at home, at work, and so forth) satisfactory at discharge?"

A question on the level of the treatment unit would be "Do the most important persons in the patients' social network regularly get information about discharge, or are they involved in discharge planning on the ward?" At the level of the whole institution, a question would be "Do other agencies and institutions supporting patients' social integration in the region know and understand the hospital's criteria for discharge?"

These sample questions illustrate the general approach. The guidelines are not a scale and are not intended to yield a score. However, they allow us to examine aspects of quality in a given care situation, to probe whether the quality matches the standards, and to decide whether and on what level a need for improvement exists. The authors of the manual do not recommend working through it systematically from the beginning to the end; rather, the reader should choose an area of practice that is of special interest or is the reader's own responsibility.

Discussion and conclusions

The approach for assessing quality of care presented in this paper and in the manual developed by the expert group (5) may be typically German. It is somewhat systematic, basic, thorough, and comprehensive, but it is also complicated and theory driven. It addresses the ethical principles of psychiatric treatment and accommodates the reluctance among staff in psychiatric hospitals in Germany to allow external monitoring and control. This reluctance may partly be due to historical experience under the Nazi regime when insufficient resistance to external political influence, among other factors, led to the killing of more than 200,000 people with mental illness or mental retardation.

This reluctance is reflected in the current structure of the German mental health care system, in which hospitals are usually independent institutions and in which patient data are protected by uniquely strict legislation. The great emphasis by the group on ethical values that are hardly measurable, such as protecting the human dignity of patients, might also be regarded as a reaction to the specific history of German psychiatry.

One might speculate that a group in the United States or the United Kingdom commissioned with a similar task of developing an assessment tool would try to work out a rating scale that could be tested for its psychometric properties and could be used in an operationalized way. Such a scale would yield scores, like BASIS-32 does (6). Application of the scale as well as analysis and interpretation of the results would be as objective as possible. In contrast, the German group has come up with an assessment tool that is not intended to be objective or standardized. It explicitly aims at supporting individualized and subjective assessment of quality of care and is based on the assumption that scores are an inadequate simplification of the subject. In the group's view, scores of standardized scales may complement the guidelines but cannot replace them.

The approach to assessment described here is complex and difficult to handle. Although the manual has 373 pages, it does not give a specific definition of quality of hospital care or outline any implications for action. It provides guidelines for various potential users on how to assess the quality of a given hospital care procedure and how to ask questions about specific aspects of it. Useful application of the guidelines requires quality management techniques. It also requires a climate within the hospital that encourages open communication and change rather than one that covers up and glosses over shortcomings and faults.

This approach is the only one that has been developed in Germany for the assessment of psychiatric hospital care. Its publication has received mixed responses (7,8,9). It was positively noted that the guidelines avoid a mere technocratic approach to quality assurance, that they address ethical issues, and that they can be integrated into different forms of total quality management still to be developed for psychiatric inpatient care in Germany. The approach was criticized for being excessively ideological, for not specifying treatment standards, and for being of hardly any practical use.

Mental health professionals in quite a few hospitals have started to use the manual in line with the more or less established quality management procedures in each hospital. Although some positive experiences have been reported, a systematic evaluation has not yet been done. It remains to be seen whether the approach presented in this paper will turn out to be step toward a practical improvement in the quality of inpatient care as intended by the German Ministry of Health.

Dr. Kunze is professor of psychiatry and medical director of the Psychiatric Hospital Merxhausen in Bad Emstal, Germany. Dr. Priebe is professor of social and community psychiatry in the department of psychological medicine at St. Bartholomew's and the Royal London School of Medicine, West Smithfield, London EC1A 7BE, United Kingdom (e-mail, spriebe@compuserve). Address correspondence to Dr. Priebe.

|

Table 1. Twenty-three quality standards in four categories for assessing the quality of psychiatric hospital care in Germany

1. Kunze H: Die psychiatrie-personalverordnung als instrument der qualitätssicherung in der psychiatrie [Staffing directive for psychiatric hospitals as an instrument for quality assurance], in Qualitätssicherung in der Psychiatrie [Quality Assurance in Psychiatry]. Edited by Berger M, Gaebel W. Berlin, Springer, 1997Google Scholar

2. Blumenthal D: Quality of care: what is it? New England Journal of Medicine 335:891-894, 1996Google Scholar

3. Lundberg GD, Wennberg JE: Quality of care: a call for papers for the annual coordinated theme issues of the AMA journals. JAMA 276:1514, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Coker M, Sharp J, Powell H, et al: Implementation of total quality management after reconfiguration of services on a general hospital unit. Psychiatric Services 48:231-236, 1997Link, Google Scholar

5. Leitfaden zur Qualitätsbeurteilung in Psychiatrischen Kliniken [Guidelines for Assessing the Quality of Psychiatric Hospital Care]. Schriftreihe des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit [Series of publications of the German Ministry of Health], vol 74. Baden Baden, Nomos, 1996Google Scholar

6. Eisen SV: Behavior and symptom identification scale (BASIS-32), in Outcomes, Assessment, and Clinical Practice. Edited by Sederer LI, Dickey B. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

7. Gaebel W: Leitfaden zur Qualitätsbeurteilung in Psychiatrischen Kliniken: stellungnahme [Guidelines for Assessing the Quality of Psychiatric Hospital Care: comments]. Nervenarzt 67:968-970, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lorenzen H: Leitfaden zur Qualitätsbeurteilung in Psychiatrischen Kliniken: stellungnahme [Guidelines for Assessing the Quality of Psychiatric Hospital Care: comments]. Nervenarzt 67:972-973, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

9. Weig W: Leitfaden zur Qualitätsbeurteilung in Psychiatrischen Kliniken: stellungnahme [Guidelines for Assessing the Quality of Psychiatric Hospital Care: comments]. Nervenarzt 67:973-974, 1996Medline, Google Scholar