Policy Reform Dilemmas in Promoting Employment of Persons With Severe Mental Illnesses

Abstract

Recent evaluations by the U.S. General Accounting Office and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill of reemployment efforts of the federal-state vocational rehabilitation program found that services offered by state vocational rehabilitation agencies do not produce long-term earnings for clients with emotional or physical disabilities. This paper examines reasons for these poor outcomes and the implications of recent policy reform recommendations. Congress must decide whether to take action at the federal level to upgrade programs affecting persons with severe mental illnesses or to continue to rely on state decision making. The federal-state program largely wastes an estimated $490 million annually on time-limited services to consumers with mental illnesses. Rechanneled into a variety of innovative and more appropriate integrated services models, the money could buy stable annual vocational rehabilitation funding for 62,000 to 90,000 consumers with severe mental illnesses. Larger macrosystem problems involve the dynamics of the labor market that limit job opportunities and the powerful work disincentives for consumers with severe disabilities now inherent in Social Security Disability Insurance, Supplemental Security Income, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Substantial employment remains an elusive goal for most persons with severe mental illnesses, which are defined by the National Mental Health Advisory Council as including schizophrenia, manic-depressive illness, major depression, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (1). The aggregate employment rate for this group is between 10 and 15 percent (2).

Congress has attempted to address the special needs of persons with severe disabilities, including those with severe mental illnesses, by creating major new initiatives, such as the amended Rehabilitation Services Act of 1973, the Title VI-C supported employment program, the amended Social Security Act of 1935, the Title 1619 Supplemental Security Income work incentives program, and the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 mandate for nondiscrimination and reasonable accommodation in the workplace. It has also exercised oversight by directing the U.S. General Accounting Office (3,4,5,6) to evaluate the reemployment efforts of the federal-state vocational rehabilitation program and of the Social Security Administration responsible for administering the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program.

The search for best practices and strategies to secure and maintain employment for people with severe mental illnesses has led the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (2) and the federal Rehabilitation Services Administration (7) to fund numerous research projects and conferences. Notable state efforts include the funding of an ambitious demonstration of the benefits and costs of interventions by integrated services agencies on behalf of persons with severe mental illnesses in three California locations (8).

This paper examines policy reform implications of recent reports by the General Accounting Office and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill bearing on the vocational rehabilitation of people with severe mental illness, as well as recommendations of the Disability Policy Panel of the National Academy of Social Insurance to improve work incentives in federal entitlement programs.

Benefits and costs of work

Work plays a pivotal role in life. It is the principal source of income and sometimes health insurance coverage. Adequate income permits the exercise of choice in the selection of goods and services according to personal preferences. Income also determines social class and place in the opportunity structure of society.

Work is considered important for persons with severe mental illnesses for reasons beyond the income it provides. First, work may aid recovery by providing structure, the opportunity for social connections, and the meaning of a normal life (9). It may also help prevent decompensation and frequent hospitalization (10,11). Second, work can sometimes end dependence on federal income support programs such as SSI and SSDI, whose rules "enforce poverty" by severely limiting savings and the accumulation of assets, and even penalize marriage (12,13). Third, work provides respite for families who would otherwise have to cope with the burden of care for an idle member throughout the day (14).

On the negative side of the ledger, the vicissitudes and insecurities of work are a source of stress and anxiety for most people that, in addition to immediate discomfort, can lead to eventual physical and mental health problems (15,16).

Program failures

Cumulative program failures often lead to pressure for legislative reform. In this section the sources of discontent that lie behind a number of emerging federal policy reform proposals are briefly described.

The federal-state vocational rehabilitation program.

Services offered by state vocational rehabilitation agencies do not produce long-term earnings for clients with emotional or physical disabilities (3). For such clients whose cases were closed as "successfully rehabilitated" in 1980, average earnings were lower in 1988 than in the years before referral for vocational rehabilitation services. Average case service expenditures for clients with emotional disabilities ($1,224) were less than for clients with mental retardation ($1,478) or physical disabilities ($1,920) or sensory disabilities ($1,744 to $2,401). Expenditures were less than $500 for the majority of clients with mental illnesses.

These low expenditures reflect a declining share of overall program funding to purchase services on behalf of clients and an increasing share spent on operations of the state vocational rehabilitation agency; operations are defined as administrative costs plus agency-provided guidance and counseling. From 1975 to 1987 case services spending declined by about 6 percent despite an overall increase in basic program funding of almost 96 percent, rising from $869 million to $1.7 billion (17).

Furthermore, best practice calls for the state vocational rehabilitation agency to purchase services from psychiatric rehabilitation providers whenever possible and to assign specialized caseloads to some counselors, as well as to locate vocational rehabilitation counselor-specialists in mental health facilities and programs (7). A study of the federal-state vocational rehabilitation system sponsored by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) found that only 12 states have implemented a statewide specialized caseload policy (9). Thus the poor outcomes documented by the U.S. General Accounting Office (3) are partly attributable to declining expenditures by the state vocational rehabilitation agency for purchase of needed quantities of specialized services from psychiatric rehabilitation providers, and they may be attributable to the minimal use of specialized caseloads or vocational rehabilitation counselor-specialists being located in mental health care settings.

In rationing available case service funds, state vocational rehabilitation agencies place artificial limits on funding and duration of contracted services for individual clients. This practice deters potential psychiatric rehabilitation contractors. Another rationing technique involves use by state vocational rehabilitation agencies of paper-and-pencil tests and psychological evaluations for assessing the vocational potential of consumers, despite considerable evidence that direct placement in a job is the best predictor of eventual vocational success (18,19). Consistent with these rationing practices are frequent complaints by consumers and family members documented in the NAMI study about the inordinate amount of time spent by state vocational rehabilitation counselors processing paper work and how little time is devoted to direct services after eligibility is established (9).

Finally, state vocational rehabilitation agencies continue to classify mental illnesses as "psychotic," "psychoneurotic," and "other personality and character disorders," terminology that follows the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-II (20), published 30 years ago. The agencies have rejected repeated advice over the years to adopt current nomenclature and classification criteria (9).

State mental health agency programs.

State mental health agencies refer far fewer consumers to the state vocational rehabilitation agency than the expected rate of 487 per 100,000 population. This figure is based on an admittedly dated estimate of the number of persons with chronic or severe mental illnesses who receive SSI or SSDI benefits (21). The average rate of referrals by state mental health agencies to vocational rehabilitation services other than programs run by state mental health agencies themselves was only 19.8 per 100,000 population, ranging from a high of 205.6 in South Carolina to zero in most states.

Only 16 state mental health agencies require inclusion of a vocational rehabilitation component in the consumer's individualized treatment or service plan (9). Increasing awareness of innovative vocational rehabilitation models has not as yet led to substantial action. Among the 30 state mental health agencies reporting knowledge of research-based innovations, such as the "choose, get, keep" model of Anthony and associates (22), Thresholds in Chicago (18), Stein and Test's Program for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) (23), and Fountain House in New York City (24), funding of such programs was minimal in nine states, moderate in 12, and substantial in only eight (9).

The average amount spent on vocational rehabilitation by all state mental health agencies came to slightly more than 3 percent of total budgets, ranging from a high of 25 percent in South Dakota to zero in most states. Despite the existence of formal cooperative agreements in most states between the state vocational rehabilitation agency and the state mental health agency, these agreements clearly do not translate into substantial referrals or expenditures by state mental health agencies.

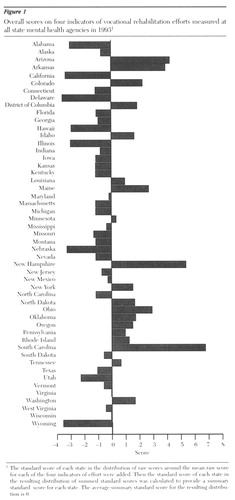

Four indicators may be used to measure and summarize the extent of vocational rehabilitation efforts made by a state mental health agency: mandatory inclusion of a vocational rehabilitation component in the consumer's treatment plan, referrals by the state mental health agency to the state vocational rehabilitation agency expressed per 100,000 population, commitment to paying for extended supported employment services, and the percentage of the state mental health agency's budget allocated to supported employment. Figure 1 presents the extent of vocational rehabilitation efforts of state mental health agencies in the 50 states and the District of Columbia based on these indicators.

Psychosocial rehabilitation programs.

A total of 138 psychiatric rehabilitation programs belonging to the International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services were surveyed by NAMI (9). These programs reported providing vocational services to only 8 to 12 percent of their total clients (9), relying on traditional vocational rehabilitation, supported employment, and transitional employment methods. Less than 7 percent of those receiving vocational rehabilitation services and 1 percent in transitional employment actually obtained an unsupported competitive job. Almost 78 percent of program clients were funded by the state mental health agency, in contrast to the 10 percent funded by the state vocational rehabilitation agency. The median dollar amount received for each client funded by the state mental health agency was $2,636, in contrast to $1,000 for clients funded by the state vocational rehabilitation agency.

The 138 psychiatric rehabilitation programs that responded to the NAMI survey voiced complaints about substantial problems they had in dealings with both state mental health agencies and the state vocational rehabilitation agency (9). Their principal allegations concerned inadequately funded services (76.8 percent of respondents); harmful procedural delays (40.6 percent); the lack of progress in resolving existing problems with the state mental health agency (32.2 percent) or the state vocational rehabilitation agency (44.1 percent); stigmatization of consumers by state funding sources, employers, and the public (29 percent); and inadequately trained state vocational rehabilitation agency counselors (20.3 percent).

Policy reform dilemmas

Assuming that Congress has the will to do something about the multiple problems uncovered by the General Accounting Office (3,4,5,6) and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (9), what are the solutions? The lengthy eligibility determination and planning process for vocational rehabilitation kills the motivation of many consumers with severe mental illnesses to persevere. Unrealistic limits on funding and duration of services imposed by state vocational rehabilitation agencies discourage the very psychiatric rehabilitation programs that have the know-how and stamina to persist in encouraging consumers to work when their symptoms are in control and to help with other needs when they are not. The traditional vocational rehabilitation process is inefficient and top-heavy with personnel who stubbornly adhere to outdated methods and a time orientation that is insensitive to the intermittent or ongoing needs of people with severe mental illnesses.

In consequence, the federal-state vocational rehabilitation program largely wastes an estimated $490 million annually on time-limited services to consumers with mental illnesses (9). Rechanneled into the vocational component of a variety of more appropriate replicative integrated services models, such as Fountain House in New York City, Thresholds in Chicago, and various PACT-type programs springing up around the country, the money could buy stable annual vocational rehabilitation funding for 62,000 to 90,000 consumers with severe mental illnesses.

The first decision facing the U.S. Congress at this point is whether to take any action at all at the federal level to upgrade programs affecting persons with severe mental illnesses or to continue to rely on state decision making. The latter policy inevitably leads to uneven results. Some states may choose to do nothing. Still others may select bits and pieces from the menu of largely untested best-practice advice based on conventional wisdom (7). A few states may even take the additional step of centering combined state vocational rehabilitation and mental health agency funds on specific consumers within the framework of an integrated mental health treatment-vocational rehabilitation plan carried out by a team of mental health and vocational rehabilitation counselor-specialists. This is the thrust of several employment intervention demonstrations currently funded by the Center for Mental Health Services (25).

Although fiddling at the margin will tidy up service delivery in accord with best-practice logic, it will not deal with the larger macrosystem problems involving the dynamics of the labor market that limit job opportunities and the SSDI, SSI, Medicare, and Medicaid entitlements that create powerful work disincentives for consumers with severe disabilities.

If the decision is to fix things at the national level, which among numerous reform proposals should receive consideration? The complexities involved and the long history of discrete legislative interventions have cumulatively produced no coherent disability policy but have instead led to widespread duplication and confusion at a very high cost for the nation (26). Should reforms helping persons with severe mental illnesses be linked to macrolevel changes in the federal cash benefit and health care financing programs to encourage return to work? Or should Congress try to anticipate and buffer the worst effects of labor market trends that adversely affect employment opportunities for people with all types of disabilities?

Or should Congress try to carve out specific reforms that would benefit individuals with severe mental illnesses, given their place at the tail-end of the labor queue—last hired and first fired (27,28)—because of compromised educational and work-skill attainments, an often life-long pattern of relapse and recurring symptoms, and the burden of societal stigma?

The Disability Policy Panel of the National Academy of Social Insurance pessimistically concluded that very few SSDI or SSI beneficiaries would ever be able to return to work (29,30). To assist the few beneficiaries who might be able to return to work, it proposed several major policy changes, including a return-to-work voucher for use by beneficiaries in shopping for rehabilitation services among public- or private-sector providers, a Medicare buy-in after return to work with sliding-scale premiums based on current earnings, and a disabled-worker tax credit to subsidize low wages.

The panel did not see how the current low level of disability benefits would act as a work disincentive, although fear of the loss of Medicare was acknowledged as such. Consumers testifying before the panel, on the other hand, were of the opposite opinion. Evidence reported elsewhere (31,32,33,34,35,36,37) buttresses the consumer position. The panel's neglect of the issue and its focus on the few who can function well enough to leave the SSDI and SSI rolls with minimal or one-time assistance leave the majority of beneficiaries with severe mental illnesses largely unaffected because of the severity of their deficits in social and work skills and their often-recurring symptoms. The service technology for returning such individuals to work at jobs paying more than $24,000 per year, which is the amount estimated to make it worth their while (37), is not yet in sight. Indeed, the Center for Mental Health Services is just now rigorously evaluating the possible cost-effectiveness of a variety of long-time prescribed best practices. They include service arrangements that integrate mental health and vocational rehabilitation services (26).

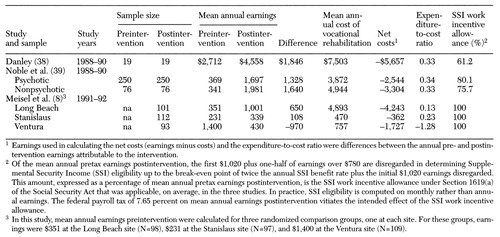

Consider the results of three recent well-funded, state-of-the-art demonstration programs that reliably measured both the annualized earnings of participants with mental illnesses and the cost of their attainment (8,38,39). As shown in Table 1, except for one site in Ventura, California, all three demonstrations could fairly claim success on the basis of statistically significant differences between pre- and postintervention earnings. Except in Ventura, the programs yielded average annual earnings between 1.5 and 5.8 times greater than preintervention earnings. Positive postintervention employment outcomes have been reported by virtually every study and modality (8, 18, 35, 38394041424344454647). In the words of Lewis Carroll's (48) Dodo, "Everybody has won, and all must have prizes."

Unfortunately, these earnings were considerably less than the $5,640 in benefits that individual SSI recipients receive annually, the $6,000 annual substantial gainful activity wage that originally established their SSI eligibility, and the more than $24,000 per year that is estimated to make leaving the rolls worthwhile (37). Further, these postintervention earnings did not translate into disposable income for participants in all study sites under the SSI work incentive allowance rules. The allowance ranged from 61.2 percent of $4,558 in the site with highest earnings to 100 percent in sites with earnings of $1,000 or less. The low-paying jobs held by the participants typically lack health care benefits and thus would not be subject to the Domenici-Wellstone mental health parity amendment that became effective in January 1998 and sunsets in September 2001 (49).

As shown in Table 1, the average annual service costs for vocational rehabilitation ranged in the studies from $470 to $7,503 per participant. The net difference between attributable earnings and the cost of their attainment was uniformly negative, ranging from -$362 at the site with lowest costs to -$5,657 at the highest-cost site. The return on these expenditures ranged from a loss of $1.28 per dollar spent in Ventura to 66 cents on the dollar in New York State.

Labor market projections to the year 2005 add to the bleak picture of what consumers with mental illnesses face, regardless of the services they receive (50). They will have to compete with other disadvantaged people, including the work-mandated population of mothers and fathers in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program and a sizable population of legal and illegal immigrants, for work in an expanding pool of low-skill, low-paying jobs. Inner-city dwellers with disabilities will join the desperate chase of too many seeking too few jobs, a labor market where older people are preferred over younger, where those from outside the neighborhood are preferred over insiders, where recent immigrants are preferred over African Americans, and where recruiting is done without advertising by personal contact with the workforce in place (51). They will have to compete as they now do for precisely the kinds of low-status jobs that provide little control over work life and thus increase the risk for stress-related heart disease and mortality (16).

Conclusions

The grim realities outlined in this paper clarify why Congress should recognize the special characteristics of people with severe mental illnesses and try to carve out specific reforms that would benefit such individuals, given their place at the tail-end of the labor queue and the burden of societal stigma they carry. The $490 million now largely wasted by the federal-state vocational rehabilitation program on ineffective services to consumers with severe mental illnesses should be rechanneled into local programs that integrate vocational and psychiatric rehabilitation services on a continuous, non-time-limited basis. Increasing nationwide the supply of psychosocial rehabilitation and PACT programs and the capacity of these programs to provide integrated vocational and psychiatric rehabilitation services would be consistent with best-practice advice (6) as well as with the thrust of the Center for Mental Health Services demonstrations (25).

Strengthening psychosocial rehabilitation and PACT programs would also set the stage for successful implementation of the macrosystem reforms recommended by the Disability Policy Panel of the National Academy of Social Insurance (29,30) and the National Council on Disability (37), especially if their return-to-work voucher proposal is modified to permit periodic payment for services rendered by providers. SSDI and SSI beneficiaries with a voucher in hand and foreknowledge of the existence of a disabled-worker tax credit and a sliding-scale Medicare or wrap-around Medicaid buy-in option would still face the challenge of finding a job that, with these subsidies pays the equivalent of more than $24,000 per year. For help in obtaining such a job, they will have to rely on vocational rehabilitation service providers willing to compete for their business and able to deliver the promised job.

Society may also receive a payoff from providing vocational rehabilitation services to consumers with severe mental illnesses in the form of intangible benefits that will help offset the tangible return of only 34 cents or less of earnings per dollar spent. Evidence is growing (52) that integrated mental health and vocational services can enhance society by reducing expensive hospitalization and the often inappropriate use of jails to control symptoms (53) by improving the social functioning and interpersonal relationships of consumers and by moderating violent behavior in the community (54,55,56). The big question is whether American society values these possible attainments enough to pay to make them more widely available.

Dr. Noble is professor in the National Catholic School of Social Service at the Catholic University of America, Shahan Hall, Washington, D.C. 20064 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Overall scores on four indicators of vocational rehabilitation efforts measured at all state mental health agencies in 19931

1The standard score of each state in the distribution of raw scores around the mean raw score for each of the four indicators of effort were addedThen the standard score of each state in the resulting distribution of summed standard scores was calculated to provide a summary standard score for each state. The avearage summary standard score for the resulting distribution is 0.

|

Table 1. Results of three studies of vocational rehabilitation programs for consumers with mental illnesses before and after interventions, including annualized earnings and the cost of vocational rehabilitation services

1. Health Care Reform for Americans With Severe Mental Illnesses. Washington, DC, National Mental Health Advisory Council, 1993Google Scholar

2. Strategies to Secure and Maintain Employment for People With Long-Term Mental Illness. Washington, DC, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, 1992Google Scholar

3. US General Accounting Office: Vocational Rehabilitation: Evidence for Federal Program's Effectiveness Is Mixed. GAO/ PEMD-93-19. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, Aug 1993Google Scholar

4. US General Accounting Office: SSA Disability Program Redesign Necessary to Encourage Return to Work. GAO/HEHS-96-62. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, Apr 24, 1996Google Scholar

5. US General Accounting Office: SSA Disability: Return-to-Work Strategies From Other Systems May Improve Federal Programs. GAO/HEHS-96-133. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, July 11, 1996Google Scholar

6. US General Accounting Office: People With Disabilities: Federal Programs Could Work Together More Efficiently to Promote Employment. GAO/HEHS-96-126. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, Sept 3, 1996Google Scholar

7. Tashjian M, Hayward J: Best Practices Study of Vocational Rehabilitation Services to Severely Mentally Ill Persons. Philadelphia, Policy Study Associates, 1989Google Scholar

8. Meisel J, McGowen M, Patotzka D, et al: Evaluation of AB 3777 Client and Cost Outcomes: July 1990 Through March 1992. Report prepared for California Department of Mental Health. Sacramento, Calif, Lewin-VHI, Inc, 1993Google Scholar

9. Noble JH, Honberg RS, Hall LL, et al: A Legacy of Failure: The Inability of the Federal-State Vocational Rehabilitation System to Serve People With Severe Mental Illnesses. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1997Google Scholar

10. Fellin P: Reformulation of the context of community based care. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 20:57-67, 1993Google Scholar

11. Hayes R, Gantt A: Patient psychoeducation: the therapeutic use of knowledge for the mentally ill. Social Work in Health Care 17:53-67, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Solomon P, Draine J: Subjective burden of family members of mentally ill adults: relation to stress, coping, and adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:419-427, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bell M, Lysaker P, Milstein R: Clinical benefits of paid work in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:51-67, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Martin DA, Conley RW, Noble JH: The ADA and disability benefits policy. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 6:1-15, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Hamburg DA, Elliott GR, Parron DL: Work and health, in Health and Behavior: Frontiers of Research in the Biobehavioral Sciences. Edited by Hamburg DA, Elliott GR, Parron DL. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1982Google Scholar

16. Marmot MG, Bosma H, Hemingway H, et al: Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet 359:231-239, 1997Google Scholar

17. Position Paper on Amendment of the Rehabilitation Act. Washington, DC, National Association of Rehabilitation Facilities, 1991Google Scholar

18. Bond G, Dincin J: Accelerating entry into transitional employment in a psychiatric rehabilitation agency. Rehabilitation Psychology 32:143-155, 1986Google Scholar

19. Roessler R, Boone S: Evaluation diagnoses as indicators of employment potential. Vocational Evaluation and Work Adjustment Bulletin 15:103-106, 1982Google Scholar

20. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1968Google Scholar

21. Goldman H, Manderscheid R: Epidemiology of chronic mental disorder, in The Chronic Mental Patient, vol 2. Edited by Menninger W, Hanna G. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987Google Scholar

22. Anthony WA, Howell J, Danley KS: Vocational rehabilitation of the psychiatrically disabled, in The Chronically Mentally Ill: Research and Services. Edited by Mirabi M. New York, Spectrum, 1984Google Scholar

23. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Evaluation of Clubhouse Model Community Based Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Final report to the National Institute of Handicapped Research (contract no 300-84-0124). New York, Fountain House, 1985Google Scholar

25. Carey MA: The employment intervention demonstration program. Community Support Network News 11:1, 1996Google Scholar

26. Berkowitz ED: Disabled Policy: America's Programs for the Handicapped. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1987Google Scholar

27. Levitan SA, Taggart R: Jobs for the Disabled. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977Google Scholar

28. Schiller BR: The Economics of Poverty and Discrimination, 6th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1995Google Scholar

29. Mashaw JL, Reno VP (eds): Balancing Security and Opportunity: The Challenge of Disability Income Policy. Final report of the Disability Policy Panel. Washington, DC, National Academy of Social Insurance, 1996Google Scholar

30. Reno VP, Mashaw JL, Gradison B (eds): Disability: Challenges for Social Insurance, Health Care Financing, and Labor Market Policy. Washington, DC, National Academy of Social Insurance, 1997Google Scholar

31. Berkowitz M: Disincentives and the rehabilitation of disabled persons. Annual Review of Rehabilitation 2:40-57, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

32. Walls RT, Zawlocki RJ, Dowler DL: Economic benefits as disincentives to competitive employment, in Competitive Employment Issues and Strategies. Edited by Rusch FR. Baltimore, Brookes, 1986Google Scholar

33. Hubbard T: What Advocates and Service Providers Should Know About the Effect of Employment on Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income. Eugene, University of Oregon Rehabilitation Research and Training Center, 1987Google Scholar

34. Jacobs HE, Wissusik D, Collier R, et al: Correlations between psychiatric disabilities and vocational outcome. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:365-369, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

35. Fabian E: Longitudinal outcomes in supported employment: a survival analysis. Rehabilitation Psychology 37:23-35, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Warner R, Polak P: An Economic Development Approach to the Mentally Ill in the Community. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1993Google Scholar

37. Removing Barriers to Work: Action Proposals for the 105th Congress and Beyond. Washington, DC, National Council on Disability, 1997Google Scholar

38. Danley K: Supported Employment Research Project: Final Report. Boston, Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1991Google Scholar

39. Noble JH, Conley RW, Banerjee S, et al: Supported employment in New York State: a comparison of benefits and costs. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 2:39-73, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Weisbrod BA, Test MA, Stein LI: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: II. economic benefit-cost analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:400-405, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Bond GA: An economic analysis of psychosocial rehabilitation. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:356-362, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

42. Malamud TJ, McCrory DJ: Transitional employment and psychosocial rehabilitation, in Vocational Rehabilitation of Persons With Prolonged Mental Illness. Edited by Ciardiello JA, Bell MD. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988Google Scholar

43. Nichols ME: Demonstration study of a supported employment program for persons with severe mental illness: benefits, costs, and outcomes. Master's thesis. Indianapolis, Indiana University, Department of Psychology, 1989Google Scholar

44. Kirszner ML, McKay CD, Tippett ML: Homeless and mental health replication of the PACT model in Delaware, in Proceedings From the Second Annual Conference on State Mental Health Agency Services Research. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, 1991Google Scholar

45. McFarlane WR, Stastny P, Deakins S: Family aided assertive community treatment: a comprehensive rehabilitation and intensive case management approach for persons with schizophrenic disorders. New Directions in Mental Health Services, no 53:43-54, 1992Google Scholar

46. Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, et al: Rehabilitative day treatment vs supported employment: I. vocational outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal 30:519-531, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Test M: Long term (seven year) continuous vocational rehabilitation with young adults with schizophrenic disorders: research findings and methodological issues raised. Presented at the Colloquium on Vocational Rehabilitation Research, sponsored by the Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation and Matrix Research Institute. Boston, Apr 17-18, 1996Google Scholar

48. Carroll L: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. New York, Airmont, 1965Google Scholar

49. Frank RG, Koyanagi C, McGuire TG: The politics and economics of mental health parity laws. Health Affairs 16(4):108-119, 1997Google Scholar

50. Kreuger AB: How will labor market trends affect people with disabilities? in Disability: Challenges for Social Insurance, Health Care Financing, and Labor Market Policy. Edited by Reno VP, Mashaw JL, Gradison B. Washington, DC, National Academy of Social Insurance, 1997Google Scholar

51. Newman KS: Inner-city labor markets: where the jobs are not, ibidGoogle Scholar

52. Clark RE, Bond GR: Costs and benefits of vocational programs for people with serious mental illness, in The Economics of Schizophrenia. Edited by Moscarelli M, Rupp A, Sartorius N. Sussex, England, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

53. Torrey EF, Stieber J, Ezekiel J, et al: Criminalizing the Seriously Mentally Ill: The Abuse of Jails as Mental Hospitals. Washington, DC, Public Citizen's Health Research Group and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1992Google Scholar

54. Torrey EF: Violent behavior by individuals with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:653-662, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

55. Dvoskin JA, Steadman HJ: Using intensive case management to reduce violence by mentally ill persons in the community. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:679-684, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

56. Estroff SE, Zimmer C, Lachicotte WS, et al: The influence of social networks and social support on violence by persons with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:669-678, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar