A Naturalistic Study of Clinical Use of Risperidone

Abstract

Follow-up data on 97 of the 101 patients at a university-based psychiatric hospital for whom risperidone had been prescribed between February 1994, when the medication was introduced, and October 1996 were reviewed an average of 102 weeks after the start of the medication. Only 28.9 percent of the patients were still on risperidone at follow-up. Patients who were maintained on risperidone were able to tolerate a higher dose with fewer side effects. The most common reasons for discontinuation were failure to achieve a therapeutic effect, noncompliance, and adverse side effects. The findings of this naturalistic study represent a cautionary consideration for the remarkable enthusiasm that surrounded the introduction of risperidone.

In two recently published practice guidelines, risperidone is listed as a first-line medication for patients with schizophrenia (1,2). The drug manufacturer has reported that since its introduction in 1994, risperidone has become “the antipsychotic most prescribed by psychiatrists,”and that it is “a standard of care for more than one million patients" (3). Advertising and educational programs that promote the use of risperidone report multiple controlled experimental studies showing the efficacy and tolerance of risperidone as an antipsychotic medication (4).

However, the applicability of these results to the naturalistic clinical setting is unclear. For example, the controlled clinical studies have strictly defined criteria for inclusion and exclusion of subjects and follow subjects for only a limited time (5). Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a more heterogeneous population on a longitudinal basis. Also, some of the studies had a relatively short wash-out period, did not control for prior medication history, and compared multiple risperidone doses to a single dose of haloperidol (6–8).

The purpose of this study is to examine the use of risperidone in a naturalistic clinical setting over a period of years. We used rates of discontinuation versus continuation as an outcome measure. Although the reasons for discontinuation of a medication are heterogeneous, discontinuation provides one index of the effectiveness of a medication (9). Theoretically, the ideal antipsychotic medication would be so well tolerated and so effective that both patients and their psychiatrists would attempt to ensure compliance.

Methods

This study was conducted at a university-based psychiatric hospital. The authors obtained a list from the hospital pharmacy of every inpatient (N= 101) for whom risperidone had been prescribed between the time it was introduced in February 1994 and October 1996. One of the authors (RB) reviewed the charts for clinical and demographic information and followed up patients discharged to the community by contacting their outpatient providers (case managers, psychiatrists, primary care physicians, or conservators).

Well over 100 prescribing physicians had been involved in making decisions about use of risperidone for the 101 patients. Few patients were treated by the same psychiatrist both in and out of the hospital, and inpatient care was provided on a large service with seven attending physicians and several cohorts of four to eight psychiatric residents who worked on the service for three-month rotations.

Data analysis consisted of comparing the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients who were and were not still on risperidone at the time of the follow-up, using chi square analyses, corrected for continuity where appropriate, for categorical variables and t tests (two-tailed) for continuous variables.

Results

Follow-up information was successfully obtained for 96 percent (N=97) of the 101 patients who had been on risperidone during their hospitalization over the 32 months sampled for the study. The mean±SD time from the start of risperidone to the follow-up was 102.1±44.6 weeks, with a range from 13.1 to 162.6 weeks.

Risperidone was prescribed for one or more of the following reasons: side effects of other neuroleptics, for 56 patients, or 57.7 percent; poor response to other medications, for 29 patients, or 29.9 percent; noncompliance with other neuroleptics, for 15 patients, or 15.5 percent; risperidone's having worked previously, for 13 patients, or 13.4 percent; and targeting negative symptoms, for five patients, or 5.2 percent. Risperidone had been started on an outpatient basis for 63.9 percent of the patients (N=62), and on an inpatient basis for the remaining 36.1 percent (N=35). As is typical of contemporary inpatient practice, a large proportion of the patients were receiving multiple psychopharmacological agents concurrently, including mood stabilizers, for 48 patients, or 49.5 percent; antidepressants, for 34 patients, or 35.1 percent; other neuroleptics, for 13 patients, or 13.4 percent; sedative-hypnotics, for 32 patients, or 33 percent; and antiparkinsonian agents, for 18 patients, or 18.6 percent.

At follow-up, 28.9 percent of the patients (N=28) were still on risperidone. The time between initiation of risperidone and the follow-up did not differ significantly between patients who had and had not discontinued the drug, suggesting that time at risk for discontinuation did not account for the pattern of use. Of the patients who discontinued risperidone, 50.7 percent (N=35) stopped it while they were inpatients and 49.3 percent (N=34) stopped it while they were outpatients.

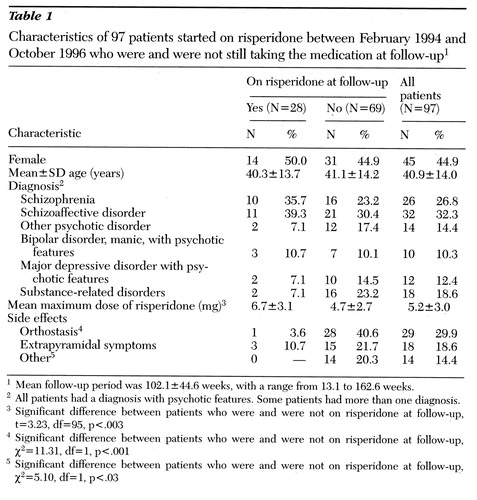

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients who were and were not still on risperidone at follow-up. Patients who discontinued risperidone had received significantly lower doses but also had significantly more side effects such as orthostasis, compared with those who had continued on the drug. Patients who were maintained on risperidone were able to tolerate a higher dose with fewer side effects. Demographic variables and diagnosis did not predict which patients discontinued risperidone.

Reasons for discontinuation of risperidone included not achieving the desired therapeutic effect, for 38 patients, or 55.1 percent; noncompliance, for 22 patients, or 31.9 percent; adverse side effects, for 26 patients, or 37.7 percent; the patient's not liking the drug and requesting a change to a different medication, for 17 patients, or 24.6 percent; and achievement of symptom remission, for six patients, or 8.7 percent. Among the 69 patients who discontinued risperidone, patients with substance-related disorders were more likely than other patients to have been noncompliant (c2=6.98, df=1, p<.01). Patients with major depressive disorders with psychotic features were more likely than other patients to have discontinued the drug due to remission of symptoms (c2=10.19, df=1, p<.002) or to have requested a switch to another medication because they did not like risperidone (c2=5.81, df=1, p<.02).

Discussion and conclusions

To our knowledge, this report describes the first longitudinal naturalistic study to follow up on whether patients remained on risperidone over the course of several years. We found that less than 30 percent of patients remained on risperidone at follow-up. Patients who were maintained on risperidone were able to tolerate a higher dose with fewer side effects and achieved a more therapeutic result.

The findings of this study represent a cautionary consideration for the remarkable enthusiasm that surrounded the introduction of risperidone. Although the drug is a useful addition to the therapeutic armamentarium, more than two-thirds of the patients in the study discontinued it, for many of the same reasons that other antipsychotic agents are discontinued. Even at low doses (below 6 mg per day), many patients reported side effects. The most common reason for discontinuation was that risperidone did not have a therapeutic effect; the patient was prescribed a different neuroleptic instead. As with other neuroleptics (10), patients with comorbid substance-related disorders were more likely than other patients to be noncompliant with risperidone.

Because this study assessed the use of risperidone in nonblind, uncontrolled conditions, an unknown number of variables other than the efficacy of the drug could have influenced the outcome. However, naturalistic studies such as the one reported here do provide information about the effectiveness of risperidone, that is, about its clinical utility in routine practice (9). An additional limitation is that the statistical power of our study to detect demographic or diagnostic correlates of discontinuation of the drug was restricted by the small number of patients who stayed on risperidone.

Antipsychotic medications, in general, are frequently discontinued, particularly among patients (such as those in our sample) who are impaired enough to require hospitalization and who have a history of poor therapeutic response, side effects, or noncompliance. The remarkable popularity of risperidone reflects the hopefulness of providers, patients, and families for a new and better neuroleptic that will be more effective and have fewer side effects than the antipsychotic medications previously available. Our findings suggest that in routine clinical practice, use of risperidone is plagued by many of the same problems that are well known with older antipsychotic medications.

Acknowledgment

This work was partly supported by grant T32-MH18261 from the clinical services research training program of the National Institute of Mental Health.

At the time of the study all of the authors were affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Sandberg is now with the department of psychology at the University of North Florida in Jacksonville. Address correspondence to Dr. Binder at the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute, 401 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, California 94143 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 97 patients started on risperidone between February 1994 and October 1996 who were and were not still taking the medication at follow-up1

1Mean follow-up period was 102.1±44.6 weeks, with a range from 13.1 to 162.6 weeks.

2All patients had a diagnosis with psychotic features. Some patients had more than one diagnosis.

3Significant difference between patients who were and were not on risperidone at follow-up, t=3.23, df=95, p<.003

4Significant difference between patients who were and were not on risperidone at follow-up,χ2=11.31, df=1, p<.001

5Significant difference between patients who were and were not on risperidone at follow-up,χ2=5.10, df=1, p<.03

1. American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Schizophrenia and Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(Apr suppl):1-63, 1997Google Scholar

2. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series Treatment of Schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12B):1-58, 1996Google Scholar

3. Janssen seeks new dose approval from FDA. Psychiatric Times, Dec 1996, p 56Google Scholar

4. Umbricht D, Kane JM: Risperidone: efficacy and safety. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:593-606, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Carter CS, Mulsant BH, Sweet RA, et al: Risperidone use in a teaching hospital during its first year after market approval: economic and clinical implications. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 31:719-725, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

6. Marder SR, Merbach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:825-835, 1994Link, Google Scholar

7. Chouinard G, Jones B, Remington G, et al: A Canadian multicenter placebo-controlled study of fixed doses of risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 13:25-49, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Johnson AL, Johnson DAW: Peer review of "Risperidone in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia: a multi-national, multi-centre, double-blind, parallel-group study versus haloperidol.” British Journal of Psychiatry 166:727-733, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Sederer LI, Dickey B, Hermann RC: The imperative of outcomes assessment in psychiatry, in Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Edited by Sederer LI, Dickey B. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

10. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA, et al: Characteristic hostility in schizophrenic outpatients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:163-171, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar