Datapoints: Routine Treatment of Adult Depression

Although an estimated 5.7 million visits are made to psychiatrists each year for the treatment of depression (1), much of the information about such treatment is derived from patients in university-based research studies (2). To better understand how psychiatrists in the community treat major depression, we surveyed a convenience sample from the American Psychiatric Association's Practice Research Network. The study served as a baseline assessment of psychiatrists' adherence to treatment recommendations in APA's Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults (3) in preparation for a quality improvement program.

The sample consisted of 210 psychiatrists, of whom 189, or 90 percent, responded. The psychiatrists were presented with case vignettes of several patients with major depression of varying severity and asked to answer specific questions about how they would manage such patients. The questions, which covered such areas as selection of initial treatment or length of maintenance therapy, were based on recommendations in the practice guideline.

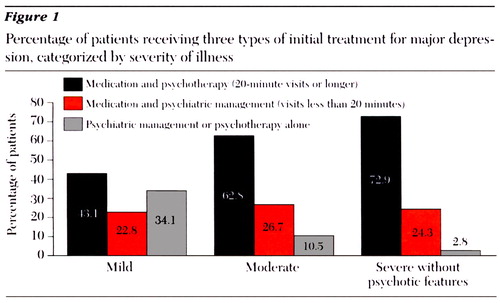

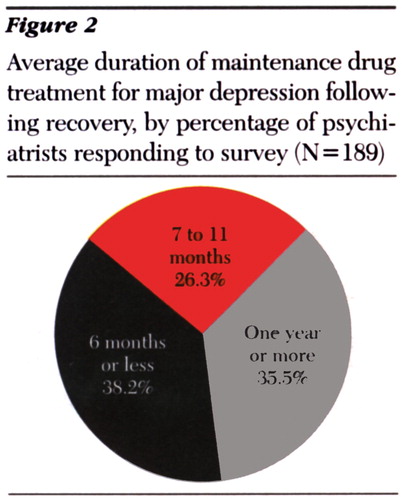

As Figure 1 shows, the initial treatment selected varied with severity of illness. Severity of illness was also linked to how long the psychiatrists generally waited to see if a patient selected for psychotherapy alone would respond before initiating a trial of medication. The average wait was 5.1 weeks in mild cases and 3.3 weeks in moderate cases. Almost 52 percent reported waiting four weeks or less to see if a patient responded to an antidepressant before recommending another medication or treatment. A third waited five or six weeks, and the remainder (16 percent) waited more than six weeks. Figure 2 shows how long the psychiatrists maintained first-episode patients on antidepressant medication following full recovery.

The survey findings reflect a consensus among psychiatrists on combining medication and psychotherapy in the treatment of major depression, particularly in its most severe forms. In keeping with the APA practice guideline, a majority of psychiatrists wait no more than six weeks before declaring a medication trial a success or a failure, and they maintain first-episode patients on medication for at least six months following full recovery.

Dr. Olfson is with the New York State Psychiatric Institute, 722 West 168th Street, New York, New York 10032, and the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University. Ms. Tanielian, Mr. Peterson, and Dr. Zarin are with the office of research of the American Psychiatric Association in Washington, D.C. Ms. Tanielian and Harold Alan Pincus, M.D., are coeditors of this column.

Figure 1. Percentage of patients receiving three types of initial treatment for major depression, categorized by severity of illness

Figure 2. Average duration of maintenance drug treatment for major depression following recovery, by percentage of psychiatrists responding to survey (N=189)

1. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient mental health care in nonhospital settings: distribution of patients across provider groups. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1353-1356, 1996Link, Google Scholar

2. Kupfer DJ, Freedman DX: Treatment of depression: "standard" clinical practice as an unexamined topic. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:509-511, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 150 (Apr suppl):1-26, 1993Google Scholar