Which Primary Care Physicians Treat Depression?

Abstract

The study attempted to determine the proportion of primary care physicians who treat depression and their characteristics. Data were from 677 respondents to a national survey of primary care physicians in Israel. Twenty-two percent always treated depression, 36.6 percent usually did, 28.6 percent sometimes did, and 12.6 percent never did. Logistic regression found that, compared with physicians who sometimes or never treated depression, those who always or usually treated depression treated more medical conditions, regarded themselves as the medical system's first contact for patients with psychosocial problems, had more frequent contact with social workers, and were more likely to have specialized in family medicine.

Patient-focused studies suggest that primary care physicians have a pivotal role in treating depression and other mental disorders (1). About half of depressed people in the United States receive treatment; of those, half are treated by primary care physicians (1). In Western countries depression afflicts approximately 6 to 17 percent of primary care patients at any given time (2). The role of primary care physicians in treating mental disorders will probably increase, in view of the trend to integrate mental and general health care (3).

The purpose of this study was to determine what proportion of primary care physicians treat depression and to understand what distinguishes them from their peers who do not typically treat depression. The study was conducted in Israel where almost all medical care is provided by sickness funds, which are equivalent to health maintenance organizations.

Methods

Data were obtained from a national study on the role of primary care physicians in Israel. Physicians were asked to respond to the Task Profiles of General Practitioners in Europe Questionnaire as part of a 30-nation study. (Copies of the study instrument are available from Wienke Boerma, Nivel, P.O. Box 1568, 3500 bn Utrecht, the Netherlands.) Respondents completed and mailed in the questionnaire, which asked about their encounters with patients who had mental health and psychosocial problems, their contact with social workers and other professionals, and their background, practice setting, caseload, medical activities, and other key areas. The physicians were asked how often they treated depression themselves without referring the patient elsewhere. They responded on a 4-point scale, with 1 indicating never, 2, sometimes; 3, usually; and 4, always.

The Israeli study used a stratified random sample of 1,065 primary care physicians drawn from a national list of 2,925. A total of 193 were found to be no longer practicing. Of the remaining 872 physicians, 677 (77.6 percent) responded. Respondents were not significantly different from nonrespondents in gender or affiliation with a sickness fund. Weighting by strata was used to compensate for nonrespondents. The mean±SD age of respondents was 48.5±11.1 years (range, 30 to 86 years).

The relationship between treatment of depression and physicians' background and practice characteristics were explored using cross-tabulations. To adjust for multiple comparisons, the significance level for chi square tests was set at <.005 (4). Stepwise logistic regression was used to estimate the increase in the probability of treating depression for each significant independent variable.

Results

Among the 677 responding physicians, 22 percent (N=146) reported that they always treated depression themselves, 36.7 percent (N=240) reported usually treating it, 28.7 percent (N=189) reported sometimes treating it, and 12.6 percent (N=83) reported never treating it. Nineteen did not respond to the question. To explore which physician characteristics were associated with treating depression, physicians were divided into two groups—physicians who typically treated depression, if they responded "always" or "usually" (386 physicians, or 58.7 percent), and physicians who did not typically treat depression, if they responded "sometimes" or "never" (272 physicians or 41.3 percent).

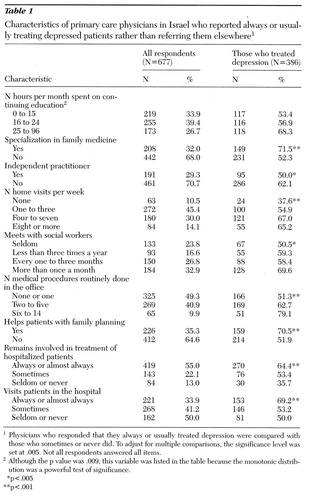

Table 1 shows the characteristics associated with physicians who typically treated depression. They included spending more time on continuing education, specializing in family medicine rather than being a general practitioner, conducting more home visits, having more frequent contact with social workers, conducting more medical procedures themselves in their office, and being involved with family planning. Another group of associated variables included being involved in the treatment of hospitalized patients and visiting these patients in the hospital.

Treating depression was also associated with being the first contact with the medical system—or gatekeeper—for other mental health and psychosocial problems. Physicians were presented with eight short statements describing a problem. For example, they were asked if they would be the first contact for a 75-year-old woman with moderate memory problems. Physicians who typically treated depression were more likely than those who did not treat depression to believe that they would be the first contact for all eight problems: elderly persons with memory problems (odds ratio=4.7, confidence interval=2.1 to 10.4), males suffering from anxiety (OR=13.9, CI=3.6 to 53.8), children suffering from physical abuse (OR= 1.4, CI=1.2 to 1.6), persons with work-related psychosocial problems (OR=3.8, CI=2.4 to 6.1), males with sexual problems (OR=3.1, CI=1.9 to 4.7), patients with suicidal inclinations (OR=2.2, CI=1.7 to 2.8), a couple with relationship problems (OR= 2.2, CI=1.7 to 2.9), and alcohol addiction (OR=1.9, CI=1.5 to 2.4).

To further characterize physicians who typically treat depression, the relationship between physicians' treating depression and their treating other medical conditions was explored. Physicians were presented with a list of 16 medical conditions and asked to report if they typically treated these problems themselves. Treating depression was significantly associated with treating seven of them: peptic ulcers (OR=3.7, CI=1.8 to 7.7), the acute phase of stroke (OR=1.8, CI= 1.5 to 7.9), congestive heart failure (OR=2.1, CI=1.5 to 2.9), colitis (OR=1.8, CI=1.6 to 2.1), brain concussion (OR=1.8, CI=1.6 to 2), Parkinson's disease (OR=2.4, CI=1.9 to 2.8), and uncomplicated diabetes type II (OR=2.9, CI=1.9 to 7.9).

The variables that were not related in bivariate analysis to treating depression were age; gender; being a salaried versus an independent practitioner; number of hours worked; number of hospital visits per week; number of phone calls per day; waiting time for an appointment; presence of support staff (a secretary or nurse); type of after-hours coverage; city size; distance from other physicians; years of experience; proximity to a specialty clinic; size of caseload; number of patients seen a day; proximity to a hospital; frequency of contact with general practitioners, specialists, hospital doctors, pharmacists, and nurses; type of emergency coverage; measures of job satisfaction; use of homeopathy; and involvement with developmental follow-up of children.

To study the independent effect and estimate the influence of each variable found to have a significant relationship in the bivariate analysis, a logistic regression model was constructed. Compared with physicians who generally did not treat depression, those who did were characterized as treating more medical conditions themselves (OR=5.8, CI=3.9 to 8.9), seeing themselves as more often being the first contact for psychosocial problems (OR=1.2, CI=1.1 to 1.3), having frequent contact with social workers (OR=2, CI=1.3 to 3.2), and specializing in family medicine (OR=1.6, CI=1.1 to 2.4). This model correctly classified 78.3 percent of physicians who treated depression and 61.7 percent of those who did not.

Discussion and conclusions

More than half of the physicians in this Israeli national survey reported treating depression by themselves, without making a referral to a specialist. This result supports findings from patient-focused studies suggesting that primary care physicians assume a major role in treating depression.

Compared with physicians who reported that they generally did not treat depression, those who did were characterized as treating more medical conditions themselves, seeing themselves as more often being the first contact in the medical system for patients with psychosocial problems, having frequent contact with social workers, and having specialized in family medicine. The strong relationship between treating depression and the number of medical conditions a physician reported treating suggests that physicians may view depression as a medical problem. It thus follows that physicians who treat more conditions would also treat depression.

The relationship between treating depression and being the first contact for patients with psychosocial problems and having contact with social workers suggests that physicians who treat depression may have a broader view of their role in patients' well-being. The increased likelihood of treating depression associated with training in family medicine probably is related to the emphasis such training places on patients' overall well-being and on treating a wide range of conditions without relying on specialists.

Because of primary care physicians' pivotal role in treating depression and because so many studies have found low rates of recognition and treatment of depression in primary care settings (5-8), considerable attention should be focused on improving treatment of depression in primary care settings.

Acknowledgments

This survey was conducted by the JDC-Brookdale Institute as part of an international study by the Netherlands Institute of Primary Health Care. It was funded by grant BMH1-CT-92-1636 from the European Community Program. The authors thank Dan Yuval, Yonah Yaphe, Shlomo Boussidan, and Avigail Dubani, who participated in conducting the survey, and Miriam Greenstein, who assisted with data analysis.

Dr. Rabinowitz is affiliated with the School of Social Work, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. Ms. Feldman is with the State of Israel Ministry of Health in Jerusalem. Ms. Gross is with JDC-Brookdale Institute in Jerusalem. Mr. Boerma is with the Netherlands Institute of Primary Health Care in Utrecht.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of primary care physicians in Israel who reported always or usually treating depressed patients rather than referring them elsewhere1

1Physicians who responded that they always or usually treated depression were compared with those who sometimes or never did. To adjust for multiple comparisons, the significance level was set at .005. Not all respondents answered all items.

2Although the p value was .009, this variable was listed in the table because the monotonic distribution was a powerful test of significance.

*p<.005

**p<.001

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Goldberg DP, Lecrubier Y: Form and frequency of mental disorders across centres, in Mental Illness in General Health Care: An International Study. Edited by Ustun TB, Sartorius N. Chichester, Wiley, 1995, p 323Google Scholar

3. Mechanic D: Integrating mental health into a general health care system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:893-897, 1994 Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Grove WM, Andreasen NC: Simultaneous tests of many hypotheses in exploratory research. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 170:3-8, 1982 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist JH, et al: Effect of primary care treatment of depression on service use by patients with high medical expenditures. Psychiatric Services 48:59-64, 1997 Link, Google Scholar

6. Higgins E: A review of unrecognized mental illness in primary care. Archives of Family Medicine 3:908-917, 1994 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ustun TB, Von Korff M: Primary mental health services: access and provision of care, in Mental Illness in General Health Care: An International Study. Edited by Ustun TB, Sartorius N. Chichester, Wiley, 1995, p 347Google Scholar