Perspectives on Adolescent Residential Substance Abuse Treatment: When Are Adolescents Done?

Locke's goal theory ( 1 , 2 ) states that specific and challenging goals lead to better performance than unclear or simpler goals. This theory has applications to adolescent substance abuse treatment in three ways. First, clients are more likely to achieve treatment goals when those goals are specific goals and when clients receive feedback on their progress toward achieving them. Second, treatment staff and parents are better able to provide feedback and reward progress when there are clear goals. Third, treatment organizations that have aligned goals with infrastructure demonstrate improved employee satisfaction and organizational performance ( 3 ). This study explored stakeholder (treatment center staff, adolescents, and parents) perspectives on a basic aspect of treatment programs—determining what indicates completion of adolescent treatment.

Adolescents with substance use disorders pose special challenges to treatment providers. First, there are unique developmental issues during adolescence—a period when teens negotiate autonomy, peer relationships, identity formation, and sexuality—as well as evidence that up to 75% of adolescents in treatment for substance-related problems also have mental disorders ( 4 , 5 ). Compared with adults, adolescents are less likely to seek treatment, and they relapse more quickly after treatment ( 4 ). Adolescents generally enter substance abuse treatment in response to external pressures from their family, their school, or the legal system ( 5 , 6 ), which suggests challenges related to resistance, motivation, and dropout ( 5 ). Despite the existence of effective interventions, such as active coordination with educational and other service providers, prosocial activities, communication and problem-solving skills training, and linkages to postdischarge continuing care services ( 7 , 8 ), most highly regarded adolescent substance abuse treatment programs do not use these key elements of effective adolescent drug treatment ( 9 ).

Another difficulty in the treatment of adolescents who abuse substances is that there may not be a widely shared set of expectations among treatment staff, researchers, and policy makers about treatment success. There is no consensus on the definition of recovery from substance use disorders ( 10 , 11 , 12 ). Laudet ( 11 ) indicated that most researchers define recovery in terms of substance use alone, most often as abstinence, but White ( 12 ) suggested that addiction researchers also use measured gradations for recovery, especially in light of evidence that resolution of substance abuse and dependence is possible for many people with mild or moderate substance use problems. Whether this is true for adolescents has not been addressed.

Another issue is whether recovery is indicated by something more than abstinence from substance use. For example, the Minnesota model states treatment goals of both lifetime abstinence and improved quality of life ( 13 ), and the adolescent community reinforcement approach states goals of abstinence, positive social activity, positive peer relationships, and improved relationships with family ( 14 ). There is some agreement that recovery is a process that goes beyond substance use to include transformational changes involving individuals, families, and communities ( 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 ). Even when concrete goals are specified, however, they may be difficult to measure; recovery progress can be measured along a developmental dimension (personal growth, maturity, and responsibility), a socialization dimension (prosocial behavior), a psychological dimension (basic cognitive and emotional skills), and a community member dimension (the individual's relationship to the community) ( 15 ). These conceptualizations of recovery seem a promising area for future research, but it is unclear whether measures of progress along these dimensions have been integrated into the stated goals of drug treatment facilities or remain abstract.

From a treatment perspective, a working knowledge of the goals of substance abuse treatment that is shared by treatment staff, adolescents, and their parents might facilitate adolescents' achievement of those goals and progress in treatment ( 14 ). From an organizational perspective, a shared understanding of the organizational mission, including what treatment success is and how it is to be achieved, can increase employee satisfaction and organizational performance ( 3 ). For researchers and policy makers, the capacity to identify treatment progress is an important step in determining therapeutic success and evaluating treatments used in substance abuse facilities. We found little research on the stated goals of substance abuse treatment agencies or the criteria by which adolescents are judged to no longer need treatment; we could find no studies comparing youth, parent, or staff perspectives on these issues. This study examined perspectives of adolescents in substance abuse treatment, their parents, and treatment center staff on what defines adolescent treatment success.

Methods

We conducted semistructured interviews with adolescents, parents, and staff at three substance abuse treatment agencies in two states. Two of these agencies were publicly funded; the third was funded both publicly and privately. Agencies had residential capacity for 15–75 adolescents, and length of treatment ranged from three to 15 months. Semistructured interviews allowed researchers to probe multiple categories related to finishing treatment and allowed participants to present opinions in their own words. The appropriate institutional review board provided oversight for human subjects protection and approved all study procedures. Interviews were conducted between April 2007 and January 2009.

Participants

Adolescents, their parents, and staff from three substance abuse treatment facilities were invited to participate in 90-minute interviews. There were 28 adolescent participants; 14% were female (N=4) and 86% were male (N=24), and they were 15–21 years of age (mean±SD=17.1±1.5). There were 30 parents (23 mothers, 77%), and 29 agency staff (19 women, 66%). Sixty-seven of the 87 participants (77%) self-identified as Caucasian, 17 (N=17, 20%) self-identified as African American, and three (N=3, 3%) self-identified as Hispanic. All adolescents were enrolled in residential substance abuse treatment programs. In some cases, two parents of an adolescent were interviewed together, thus resulting in 26 interviews among 30 parents; each parent's statements were counted separately. Staff included mostly direct-care treatment and counseling staff (N=17, 59%) and, to a lesser degree, clinical and agency directors (N=7, 24%) and other ancillary staff (nurse or administrator; N=5, 17%).

Interviews and analysis

Parents and staff provided informed consent to take part in interviews. If youths were 18 or older, they gave informed consent; if youths were under 18, their parents gave consent and youths provided their assent. Trained researchers and research assistants conducted individual interviews in person at the treatment facilities with all adolescents and staff and with most parents; interviews were conducted by phone with several parents. Content addressed treatment history, circumstances involved in the present use of services, placement transitions for admission to the substance abuse treatment center, and plans after treatment. On the topic of finishing treatment, participants were asked, "How will you know when [you/your child/youth in this agency] no longer need(s) substance abuse treatment?" and were asked follow-up questions if answers were unclear.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We analyzed interviews with Atlas.ti 5.2 software, which aids in coding, organizing, and retrieving qualitative data ( 16 ). Four analysts coded the interviews; consensus was sought to ensure consistent and reliable data. After coding was completed, analysts reviewed all coded material related to no longer needing treatment. Interpretations were refined through an iterative process in which we organized data into broad categories and then modified the categories as analysis continued. We grouped themes logically into four major areas: substance use and treatment-related changes, behavioral changes, internal changes, and other. Within specific categories, we included only one answer per person per category to ensure that no group or category was overrepresented; for example, if a respondent suggested both "being drug free" and "not using drugs," this answer was counted only once in the "not using drugs" category. This process helped to ensure that the themes identified corresponded faithfully to the stated beliefs of the interview participants.

Results

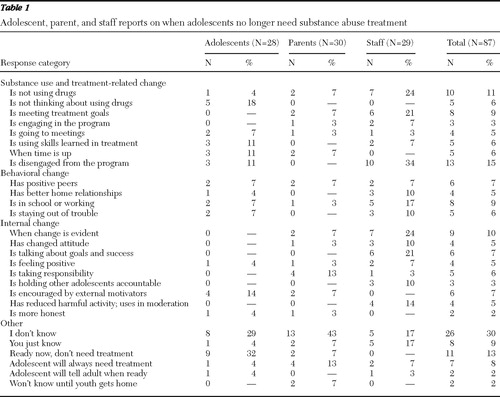

Analysis of responses provided by 87 interview participants resulted in 175 unique answers to the question, "How will you know when you no longer need treatment?" Adolescents (N=28) provided 50 answers (29%), an average of 1.8 answers each, and parents (N=30) provided 45 answers (26%), an average of 1.5 answers each. Staff (N=29) provided 80 answers (46%), an average of 2.8 answers each. Responses were organized by theme ( Table 1 ).

|

Adolescents

Among substance use and treatment-related changes, adolescents were most likely to respond that not thinking about drugs was a signal of readiness to leave treatment (18%). For example, one adolescent described his progress in terms of being able to "go a long time without being able to think about [using drugs]"; he indicated that he knew he would be finished with treatment when "I don't crave them at all and never really think about [drugs]."

Few adolescents listed behavioral changes as an indication of treatment completion (for example, associating with positive peers, going to school or working, and staying out of trouble), with only one or two responses (7%) in each category. Adolescents were the least likely of the participant groups to mention internal changes (22%), such as changes in attitude, self-perception, sense of responsibility, or goal setting. Adolescents who mentioned internal changes spoke most frequently about internal changes that were motivated by external factors (N=4, or 14%). For example, one adolescent spoke about not needing treatment because his family motivated him to quit drugs: "I know I need to change because this reason right here, and I never had that reason til a few months ago: my child and my family. That's my reason." Another adolescent spoke more abstractly as he described needing external motivation: "I would have to want to [quit], I would have to have a reason, a good reason to quit … I quit for a girlfriend once."

Adolescents also reported ambiguous responses about when they would be ready to leave treatment, including "I don't know" (29%) or saying that they did not think they needed treatment (32%).

Parents

Among substance use and treatment-related changes, parents endorsed several indicators of knowing when treatment would no longer be needed but only in small numbers for each category. Responses indicated that some parents look to others with more expertise, relying either on the evaluation of staff or the ruling of the courts for their determination of their child's readiness to leave treatment. For example, one parent responded that her child would be ready to leave treatment "when the program feels he has passed everything," and another parent said her son would be ready "when the courts say he's done." Parents also listed responses related to their child's behavioral changes, and no parents mentioned improved home relationships as an indication that their child would be ready to leave treatment.

Parents were most likely to say that they did not know what would indicate their child was finished with treatment (43%) or that they thought their child would always need treatment (13%). Parents' responses seemed pessimistic; for example, several parents questioned how one could ever know when treatment was no longer needed. "Unfortunately, I don't know that we're going to get to [my son no longer needing treatment]," one parent said. "I would like to say it's going to be in the next couple of months, that he's going to wake up to reality, that things are going to turn over and he's going to want to make this change, but after being in there for almost two months we're still not there.… I honestly don't know … if this is going to be a lifetime thing, or what." Furthermore, in contrast to their child's belief that there would come a time when he or she wouldn't think about drug use all the time, parents conceptualized recovery as an ongoing process. One parent said, "I don't think it's something you stop doing. I think it has to be part of your life."

Staff

Staff were the most likely of all three groups to mention "not using drugs" as a signal that treatment was completed (seven staff responses of ten mentions across all groups), but the most common substance use or treatment-related response among staff (34%) was that they would know when an adolescent no longer needed treatment when the teen started disengaging from the program. Staff at all agencies suggested that there was a "window of opportunity" to treat adolescents, after which they begin to "regress" and treatment becomes "counterproductive." As one staff member commented, "[With] some kids you just get the idea; we call it 'cooked': They're done, they've been there six months or what not, and they just start to—it's almost like they're drained, like they can't focus any more on the treatment things." Staff were not clear how they identified this stage with clients and indicated that after this point treatment gains were unlikely.

Staff were more likely than other groups to describe behavioral changes (N=13 responses). One staff member described several behavioral criteria in succession: "I'm able to talk with the family and get reinforcement [that the adolescents are] going to school, grades are improving, relationships at home are better, they're hanging out with peers approved by their family." Twenty-one percent of staff mentioned "meeting treatment goals" as an indicator of treatment completion but generally did so without giving concrete examples of what these goals were or how they might represent a particular treatment philosophy.

Twenty-four percent of staff also discussed internal markers of change—growth, maturity, changes in perception—and 21% spoke more specifically about how the ability of adolescents to discuss success and accomplish goals signaled their readiness to finish treatment. One staff member remarked on such changes at length: "It's a sense they 'get it' when you're talking to them and you start seeing … they're growing, and they're able to see beyond the moment and not be looking in the past.… It's not just going along with the system, it's not just following the structure.… It's understanding what the impact of their usage on their life has been. To me that's when … I'm aware they're okay to go home."

Staff also provided ambiguous answers. In addition to five staff members (17%) indicating that they "don't know" when an adolescent is ready to leave treatment, an equal number indicated that they "just know" when an adolescent is ready to leave treatment. One staff member explained it by saying, "It's instincts really, being able to be in tune with your instincts, really being in tune with that client, because you know the difference [when a client is ready to be discharged]." These statements suggest that staff may rely more on personal judgments and instinct than they do on evidence-based criteria of treatment success.

Discussion

These study findings indicate that more than a third of staff did not provide clear, evidence-based criteria for treatment goals, a third of adolescents felt they did not need substance abuse treatment (rejecting goals), and about half of parents did not know what would indicate that their child was finished with treatment. These findings are consistent with scientific literature suggesting that there is little consensus on the definition of recovery ( 10 , 11 , 12 ). These findings also suggest that there is opportunity for improvement, given that many statements were consistent with goals from the Minnesota model ( 13 ) and adolescent community reinforcement ( 14 ) for abstinence, improved quality of life, positive peer relationships, and improved relationships with family.

This research suggests that adolescents come to their own conclusions about treatment either in the absence of or despite explicit guidance and direction from the treatment agency. In either case, adolescents reported few concrete markers to evaluate their progress toward goals and had a narrow conceptualization of the types of changes that would suggest treatment completion. Resistance and lack of motivation are typical challenges in adolescent treatment ( 5 ) and inhibit goal attainment ( 2 ). We speculate that despite these challenges, the use of clarifying goals, provision of feedback, and recognition of progress via rewards may nevertheless increase the likelihood of recovery ( 1 , 2 ).

Parents' statements indicated that many are not clear about the goals of substance abuse treatment and suggested that they are experiencing frustration and stress that may limit their ability to contribute to their child's recovery. Although few adolescent programs include family-focused treatment ( 9 ), we speculate that specific efforts to inform parents about treatment goals and recovery (such as abstinence from substances and associating with positive peers), such as those in adolescent community reinforcement ( 14 ), may help parents contribute to the treatment process and may reduce parents' feelings of frustration, stress, and hopelessness.

Many staff, who arguably should be the most knowledgeable about goals for adolescent substance abuse treatment, reported that they "don't know" or "just know" when treatment is no longer needed, indicating a disconnection in how theory and research inform practice ( 17 ). Staff commonly indicated that they know treatment is no longer effective when adolescents "regress" or disengage from treatment, which suggests that further inquiry should address the optimal length of adolescent substance abuse treatment. Furthermore, these statements may point to a shift from treatment models that are open ended or ongoing to ones that are time limited under current managed care models or constraints of criminal justice requirements. For example, programs to which many adolescents are referred from the criminal justice system could develop a perspective of treatment focused more on the amount of time spent in the program rather than on completion of specific goals. Adolescent substance abuse treatment programs have been challenged to improve their quality and performance ( 9 ), and management practices within control of the program (such as performance monitoring) have been associated with improved performance ( 18 , 19 ). Ensuring that staff have a consistent, specific, and clear understanding of the treatment mission could increase their ability to provide feedback to clients, reward clients' progress toward goals ( 1 , 2 ), and increase organizational performance ( 3 ).

The study's limitations suggest that caution is needed in generalizing these findings. Responses from a nonrandom sample at three residential agencies are necessarily limited in generalizability (for example, in regard to outpatient treatment), but there is no evidence to suggest that these findings are highly unusual. Not all staff respondents were clinicians; however, it can be argued that it would be good practice for all staff in a residential treatment facility to have a similar understanding about treatment goals. Finally, agency-specific characteristics, such as culture or climate, may affect staff, parents, and clients. Additional research that explores these issues in a larger and more representative sample, including outpatient program staff, can further elucidate the nature of these phenomena.

Conclusions

Adolescent recovery from substance abuse or dependence requires the partnership of treatment staff, family members, and adolescents to focus on specific recovery-oriented goals ( 9 ). This study did not explore the framing of goals (in terms of the Minnesota model, therapeutic community, or another approach), but these findings suggest that there was not a shared perspective of treatment goals among staff, parents, and adolescents. Future research should clarify how evidence-based goals shared among multiple stakeholders may be associated with positive outcomes for youths and how organizational culture can influence the presence of shared goals. Substance abuse treatment agencies and their patients may benefit from ensuring that staff, parents, and adolescents are aware of consistent and clear goals of treatment to promote more effective treatment and improve collaboration toward adolescents' recovery.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant K23-DA020487 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors appreciate the assistance of Michele Pollock, M.S.W., Mary Cavaleri, Ph.D., L.C.S.W., James Rodriguez, Ph.D., and Jacob Hyman, B.A.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Locke EA: Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 3:157–189, 1968Google Scholar

2. Locke EA, Shaw KN, Saari LM, et al: Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychological Bulletin 90:125–152, 1981Google Scholar

3. Bart CK, Bontis N, Taggar S: A model of the impact of mission statements on firm performance. Management Decision 39:19– 35, 2001Google Scholar

4. Sussman S, Skara S, Ames SL: Substance abuse among adolescents. Substance Abuse and Misuse 43:1802–1828, 2008Google Scholar

5. Winters KC: Treating adolescents with substance abuse disorders: an overview of practice issues and treatment outcomes. Substance Abuse 20:203–225, 1999Google Scholar

6. Waldron HB, Kern-Jones S, Turner CW, et al: Engaging resistant adolescents in drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 32:133–142, 2007Google Scholar

7. Garner BR, Godley SH, Funk RR, et al: Exposure to adolescent community reinforcement approach treatment procedures as a mediator of the relationship between adolescent substance abuse treatment retention and outcome. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 36:252–264, 2009Google Scholar

8. Garner BR, Godley MD, Funk RR, et al: The Washington Circle continuity of care performance measure: predictive validity with adolescents discharged from residential treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 38:3–11, 2010Google Scholar

9. Brannigan R, Schackman BR, Falco M, et al: The quality of highly regarded adolescent substance abuse treatment programs: results of an in-depth national survey. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 158:904–909, 2004Google Scholar

10. Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel: What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 33:221–228, 2007Google Scholar

11. Laudet AB: What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 33:243–256, 2007Google Scholar

12. White WL: Addiction recovery: its definition and conceptual boundaries. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 33:229–241, 2007Google Scholar

13. Owen P: Minnesota Model: Description of Counseling Approach. Pub no 00-415. Washington, DC, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2000Google Scholar

14. Godley SH, Meyers RJ, Smith JE, et al: The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach for Adolescent Cannabis Users. Pub no SMA 01-3489. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar

15. Kressel D, De Leon G, Palij M, et al: Measuring client clinical progress in therapeutic community treatment: the therapeutic community Client Assessment Inventory, Client Assessment Summary, and Staff Assessment Summary. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 19:267–272, 2000Google Scholar

16. Muhr T: User's Manual for ATLAS.ti 5.2. Berlin, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2004Google Scholar

17. McCarty D, Edmundson E Jr, Hartnett T: Charting a path between research and practice in alcoholism treatment. Alcohol Research and Health 29:5–10, 2006Google Scholar

18. D'Aunno T: The role of organization and management in substance abuse treatment: review and roadmap. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 31:221–233, 2006Google Scholar

19. Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK, Roman PM: Availability of integrated care for co-occurring substance abuse and psychiatric conditions. Community Mental Health Journal 42:363–375, 2006Google Scholar