Ethnic Differences and Similarities in Outpatient Treatment for Depression in the Netherlands

Health services should be accessible to patients regardless of their ethnic backgrounds ( 1 , 2 ). Nevertheless, individuals with non-Western racial-ethnic minority backgrounds living in Western countries appear to receive outpatient mental health care less often than members of the ethnic majority ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). The process and outcomes of treatment are considered to be more complex and less favorable for minority groups as well; differences have been reported regarding waiting and consultation times, follow-up rates, ability to understand physicians' explanations, patient satisfaction, and early treatment dropout ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ).

However, previous studies in this area have focused largely on minority groups in the United States and Great Britain. The external validity of these studies regarding health care settings in (other) European countries is uncertain, considering the variation between studies and countries with respect to the historical background of migration to the host countries (including slavery, decolonization, or labor migration), the definition of minority status (based on self-identification, religion, or country of birth), and health care systems (with or without general practitioners or family practitioners serving as gatekeepers to specialized mental health care, and with or without mandatory health insurance).

This article reports on ethnic differences in treatment intensity and quality of outpatient mental health care for depression in the Netherlands, using data from a nationwide longitudinal psychiatric case register. It focuses on immigrants from Turkey, Surinam, Morocco, and the Dutch Antilles. Immigrants from Turkey and Morocco make up the largest part of the migrant population in Europe, first arriving in the mid-1960s because of labor shortages. Migration from Surinam and the Dutch Antilles began a decade later, when the former Dutch colony Surinam declared its independence and economic circumstances in both Surinam and the Dutch Antilles were unfavorable.

The Netherlands, like the United Kingdom ( 12 ), has a referral system, in that patients must visit a general practitioner before consulting a medical specialist. General practitioners subsequently have to suspect and recognize a condition before they can decide to refer a patient to specialized services ( 13 ). Mental health care is organized into general, categorical, and specialized institutions and among independently operating psychologists, psychotherapists, and psychiatrists. Health care is financed by mandatory basic insurance packages (since 2006), of which the contents are defined by the government. Supplementary insurance packages are optional. Before 2006, everyone earning less than a threshold income had public insurance, and those with higher incomes were obliged to have private insurance ( 14 , 15 ).

Depression is more prevalent among people in ethnic minority groups ( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ), and some studies suggest that the quality of Dutch mental health care is less than adequate for these groups ( 22 , 23 , 24 ). According to Andersen's ( 25 ) behavioral model, disparities may be related to predisposing characteristics (including gender, age, and marital status), enabling characteristics (such as education), and need factors (such as depression severity). Ethnic minority background, for example, is associated with lower levels of language proficiency and health literacy ( 26 ). In addition, in countries where Islam is prominent, mental illness is often surrounded by taboo and considered a consequence of not abiding by Islamic rules ( 27 , 28 ). We tested the hypothesis that, taking into account factors such as gender, age, marital status, and depression severity ( 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ), ethnic minority background is associated with lower treatment intensity and poorer quality of care.

Methods

Data source

We extracted data from ZORGIS, a national case register introduced in the Netherlands in 2000 to facilitate health care policy and research. ZORGIS contains longitudinal data from Dutch mental health care institutions. This study focused on the registration period 2001–2005, which includes 1,845,709 episodes of care for 1,345,660 clients. In ZORGIS, an episode of care is defined as the interval between registration with a service for a mental health problem and a final or last contact with that service.

This study was limited to general mental health care, which includes integrated mental health care, general psychiatric hospitals, and institutions for community-based mental health care. ZORGIS covers the larger part of general mental health care consumption among adults between 2001 and 2005, which can be derived from three observations. First, more than 75% of institutions for general mental health care provided data for ZORGIS. Second, organizations that provide data to ZORGIS constitute geographical service areas in which most (> 75%) of the Dutch adult population lives. Third, a comparison with data from the Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZa; www.nza.nl/organisatie/sitewide/english ) showed that ZORGIS contains data on more than 75% of the mental health care services rendered in the country.

Because ZORGIS contains clinical data derived from case files used in daily practice and because patients were not treated according to a study protocol, the Dutch law on medical research does not require patients to sign an informed consent. Anonymity was guaranteed by encoding patients' personal details. The design of this study was approved by a scientific guidance committee assigned by the Netherlands Mental Health Care Association, which maintains the ZORGIS database.

Outcomes

A distinction was made between treatment intensity and quality of care ( 33 ). Treatment intensity was calculated as the total number of outpatient contacts within an episode, divided by the episode length (in months). For example, a treatment intensity of 2.0 indicated that a client had an average of two ambulatory contacts per month.

Quality of care was measured with three indicators. First, timeliness indicated absence of delay in receiving needed services, which is important because increases in waiting times appear to be associated with worse prognosis (such as increased risk of hospitalization or suicide) ( 34 ). Timeliness was defined as concordance between urgency of the first contact according to the referrer and the actual time between registration at an institution for mental health care and the first treatment contact. For instance, if a client was considered to need treatment within 24 hours but had to wait three days, timeliness was rated 0 (no). If the patient was seen within a day, timeliness was rated 1 (yes).

Dropout, or the premature interruption of treatment, was regarded as indicative of treatment nonadherence ( 35 ). In ZORGIS dropout is judged and registered by the therapist and defined as an inappropriate termination or discontinuation of the treatment episode. Dropout was indicated when the episode was ended on the client's initiative, without the provider's approval.

Early reregistration was defined as a new registration for mental health care within three months after termination (routine termination or as a result of dropout) of the previous episode. As such, early reregistration was regarded as the outpatient equivalent of early readmission in inpatient care ( 36 ). No distinction was made with respect to clinical background or diagnosis, so that reregistrations for disorders other than depression were considered as well. No distinction was made between outpatient and inpatient care.

Predictor variables

Ethnic background was defined according to the client's country of birth ( 37 ). Persons were non-Dutch if they and at least one of their parents were born abroad (first-generation immigrant) or if they were born in the Netherlands but at least one parent was born abroad (second-generation immigrant). A person was ethnic Dutch if both parents were born in the Netherlands regardless of that person's country of birth. The strict application of this definition was hampered by partly missing information on parents' country of birth. Ethnicity was therefore calculated with best available evidence. [An appendix providing further detail about how ethnic background was defined is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org. ]

Illness characteristics included presence of a psychiatric condition comorbid with depression (specifically, a registered comorbid disorder on DSM-IV axis I) and severity and recurrence of the major depressive episode. Using DSM-IV codes 296.21–296.24 and 296.31–296.34, we could discriminate between first episodes and recurrent episodes and between mild, moderate, and severe depression episodes. If the diagnosis at the start of a treatment was missing (approximately 60%), the diagnosis at the end of an episode was used (if available).

Sociodemographic information included age, gender, marital status, and degree of urbanization of the residential area. The latter was based on address density and was categorized as rural, slightly urbanized, moderately urbanized, highly urbanized, and very highly urbanized ( 38 ).

Inclusion criteria

In total, 17,270 episodes were included in the analyses; these episodes were selected with the following criteria. First, we selected all episodes that were for outpatient care, were first registrations within the data set (person-based), started after December 31, 2000, but on or before December 31, 2005, were not for "significant others" (that is, children or husbands), and involved adult clients (between ages 18 and 65). This resulted in 523,530 episodes. Of these, 33.2% had no diagnosis registered. A missing-value analysis was conducted, indicating that the diagnosis was more often missing among ethnic Dutch, elderly persons, men, inhabitants of less urbanized areas (that is, in rural areas), married persons, and in cases of less timely treatment and less dropout (p<.001 for each). Differences regarding treatment intensity (.02 fewer treatment contacts per month) and early reregistration (.01% more often if diagnosis was missing) were significant but negligible.

Among those with a known diagnosis, there were 32,219 episodes eligible for inclusion (specifically for major depression, with known depression severity and recurrence). Episodes with incomplete information (N=14,949, 46.4%) were excluded from the analyses. Compared with the analytic subsample, excluded episodes more often involved ethnic Dutch, men, clients from urban areas, and first episodes (p<.001 for each). Differences regarding outcome measures, although statistically significant, were negligible. That is, excluded episodes had 1.0% less timeliness of the initial contact (p=.047) and on average .07 contacts per month less (p=.028).

Statistical analyses

Ethnic differences were tested with analysis of variance (for means) and chi square tests (for proportions). Post hoc comparisons were conducted with Tukey's method and the Mann-Whitney U test. Furthermore, multivariate analyses were conducted with linear regression (intensity), logistic regression (timeliness), and Cox regression (dropout and reregistration). We entered the covariates in a predefined hierarchical format to evaluate the contribution of covariates separately. With the first block we entered only ethnic background; with the second and third blocks we included depression severity ( DSM-IV axis I comorbidity, depression severity, and depression recurrence) and demographic information (gender, age, marital status, and urbanicity of the client's area of residence), respectively. The analyses were done with SPSS, version 17.0.

Results

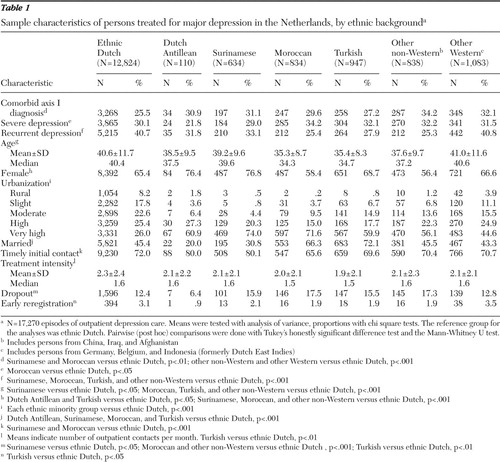

Comorbid DSM-IV axis I conditions were more frequent among Surinamese, Moroccan, other non-Western, and other Western clients than among ethnic Dutch ( Table 1 ). Compared with the ethnic Dutch group, the proportion of clients with severe depression was significantly different (higher) only for Moroccan clients. Depression episodes recurred significantly less often among clients from ethnic minority groups, with the exception of Dutch Antilleans and other Western immigrants. Persons from ethnic minority groups were generally younger than ethnic Dutch. There were significantly more female clients among Dutch-Antillean, Surinamese, and Turkish groups but fewer among Moroccans and other non-Western groups, compared with ethnic Dutch. Persons from ethnic minority groups more often lived in urban areas than did ethnic Dutch. Compared with ethnic Dutch, fewer Dutch Antillean and Surinamese clients and more Turkish and Moroccan clients were married.

|

Initial treatment contacts were more likely to occur within an appropriate time frame among Surinamese clients but less likely among Moroccans ( Table 2 ), compared with ethnic Dutch clients. Timeliness of contacts for comparisons of Surinamese and ethnic Dutch and of Moroccan and ethnic Dutch were confirmed in the regression analysis ( Table 2 , model 1). When differences in episode severity (model 2) and demography (model 3) were taken into account, timeliness was worse among Turkish and other non-Western immigrants; lower comorbidity, higher age, and living in a highly urbanized neighborhood were associated with greater timeliness of the initial contact.

|

Dropout from depression treatment was significantly higher among immigrants than among ethnic Dutch, except for Dutch Antilleans and Western immigrants ( Table 2 ). Differences in depression severity (model 2) and demographic characteristics (model 3) explained most differences in dropout, or absence thereof, although the change in magnitude of the odds ratio was sometimes negligible. In the final regression model Dutch Antillean background was in fact associated with less dropout. More severe and recurrent depression episodes, as well as being female and older, were associated with lower rates of dropout. Living in moderately or highly urbanized neighborhoods was associated with more dropout.

Early reregistration for treatment of depression occurred less often among Turkish clients. Moroccans and clients of other non-Western ethnic background were less likely than ethnic Dutch to have early reregistration (model 1). In the second and third models, ethnic background was no longer associated with early reregistration, although the odds ratio in some cases hardly changed. Greater depression severity, recurrence of depression, and higher comorbidity were associated with higher early reregistration. Being married was associated with lower early reregistration.

Treatment of depression episodes was less intensive for Moroccan and Turkish clients than for ethnic Dutch clients ( Table 3 ). Differences remained (model 2) and even increased (model 3) when depression severity and demographic characteristics were taken into account. In the final model, intensity was significantly lower for other non-Western minorities as well. Having a more severe and recurrent depression, as well as living in moderately or highly urbanized neighborhoods, was associated with more intensive treatment, whereas more comorbidity, higher age, and being married were associated with lower treatment intensities.

|

Discussion

This study focused on ethnic differences in outpatient mental health care for depression, using longitudinal data from a nationwide case register from the Netherlands. Taking into account depression severity and demographic characteristics, we found that clients with Moroccan, Turkish, and other non-Western ethnic backgrounds had less favorable results. Yet differences were small. Moreover, treatment characteristics were more favorable for Surinamese and Antillean clients. The data therefore do not support the idea that mental health treatment is generally less favorable for clients from ethnic minority groups.

An important strength of this study is the availability of longitudinal data from a nationwide psychiatric case register, which covers most mental health care in the Netherlands. Therefore, the database includes data for a large number of clients with outpatient treatment for depression. As a consequence of the large sample size, we were able to conduct a detailed analysis of ethnic background and differences, and capturing this diversity is an additional strength of this study.

A limitation of the study is the large number of clients who were omitted from the analysis because data on ethnic background were missing. We cannot rule out the possibility that these data were more likely to be missing for a particular group, which may have biased our results. However, certain findings suggest that ethnic Dutch were overrepresented in the sample that was excluded because of unknown ethnic background. For example, only 47% of the clients with missing data lived in highly urbanized areas (data not presented), whereas most non-Western immigrants in the Netherlands (70%–90% in our sample) live in these areas. In addition, some treatment characteristics of clients with unknown ethnic background were similar to or better than those of ethnic Dutch clients (73.8% timeliness and 1.4% early reregistration). Thus, if ethnic Dutch with more favorable treatment characteristics were overrepresented in the group excluded from analysis, this would have influenced our overall conclusion, in that some differences would have been accentuated (such as timeliness among Moroccans) and others would have been moderated (such as early reregistration among Moroccans).

A second limitation concerns the administrative indicators of quality of care, which are generally "less sensitive measures of health care processes than consumer derived indicators" ( 39 ) and often lack validation ( 40 ). For example, our criterion of three months to define early reregistration may be somewhat arbitrary. Post hoc sensitivity analysis showed that varying this criterion to six and nine months, respectively, altered our results, in that (uncorrected) ethnic differences decreased and even disappeared completely (with nine months; data not presented). Thus the finding that individuals with Moroccan or other non-Western ethnic background had lower rates of early reregistration depends on the definition of early reregistration.

Third, the setting of our study (the Dutch health care system in which general practitioners serve as gatekeepers to specialized mental health care) also limited the generalizability of our findings. That is, the results refer to people who had a need for mental health care, who contacted their general practitioner, who in turn recognized their needs and finally referred them. Although it has been suggested that Dutch general practitioners adequately refer patients to specialized health services regardless of patients' ethnic background ( 23 ), there is a lack of studies investigating whether recognition of mental health problems among immigrant groups is also adequate ( 41 , 42 , 43 ).

Fourth, the data did not contain information on socioeconomic status. Therefore, it was not possible to determine whether seemingly ethnic differences were in reality the result of economic or instrumental barriers. However, in a setting of universal medical insurance coverage—as is the case in the Netherlands—there are indications that income is not a major determinant of mental health service use ( 44 ). Moreover, Young and colleagues ( 45 ) found that income and insurance are unrelated to appropriateness of depression care.

Regardless of these limitations, it was striking that unfavorable findings mostly concerned Turkish and Moroccan clients, whereas results were better for Surinamese and Dutch Antilleans. Here, better Dutch language proficiency among former residents of Surinam (a former colony of the Netherlands) and the Dutch Antilles (still a part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands) may play a role, because communication is obviously more complicated if patient and provider do not share the same language ( 46 ). Various studies have established that this and other communication barriers can negatively affect patient satisfaction, treatment compliance, perceived quality of care, and trust in the physician ( 47 , 48 , 49 ).

The evidence of a beneficial influence of common language between client and practitioner, however, remains limited, because dropout was higher among Surinamese but not among Antilleans. Other factors thus must be considered as well, such as different attitudes toward mental health care and ethnic matching between client and therapist ( 32 , 50 , 51 ). Surinamese clients, for that matter, have been found to value ethnic matching quite highly ( 52 ), although the number of Surinamese mental health care professionals in the Netherlands is relatively low. It is unknown to what extent Dutch Antilleans value ethnic matching.

There were also differences between Turkish and Moroccan clients. For example, there was a higher risk of delays in the initial treatment contact among Moroccans. Differences in depression severity may explain this, in that a higher degree of comorbidity among Moroccans may have complicated the diagnostic process in the pretreatment phase, causing longer delays to initiating needed treatment. The reverse relationship also may have occurred, with treatment delays resulting in more instances of comorbidity. A similar explanation (a higher chance of escalation of problems) has been put forward for the higher frequency of compulsory admissions in relation to psychosis among some non-Western immigrants in the Netherlands ( 53 , 54 ).

Conclusions

Differences in treatment associated with ethnic background were generally small or moderate, sometimes hinted at a more favorable situation for persons from ethnic minority groups, and sometimes appeared to be explained by variations in demographic and illness characteristics. Without thus minimizing the importance of statistically significant unfavorable associations, we believe that their clinical relevance should be considered as well. In that respect, the Netherlands—like other countries—has a considerable history of adapting health services, including mental health services, to suit clients from different cultures ( 55 , 56 ). The more favorable results, presented here and in other reports ( 57 , 58 ), may have to be viewed in this perspective. In the United States, for example, racial and ethnic differences regarding "treatment of common mental disorders, disparities in counselling/referrals for counselling, antidepressant medications, and any care vastly improved or were eliminated over time in psychiatric visits" ( 59 ). Further research will have to establish whether this is happening in the Netherlands as well.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was conducted within the framework of the academic collaborative between the Amsterdam Municipal Health Service and the Academic Medical Centre of the University of Amsterdam. This academic collaborative is funded by its partners and by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). The authors acknowledge the Dutch Mental Healthcare Association (GGZ Nederland) for granting access to the ZORGIS database and for providing valuable comments on preliminary results of the study. Also, the authors thank Ronald Geskus, Ph.D., for his statistical advice.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Bhugra D, Mastrogianni A: Globalisation and mental disorders: overview with relation to depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 184:10–20, 2004Google Scholar

2. Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:479–481, 2001Google Scholar

3. Snowden LR, Wallace NT, Kang SH, et al: Capitation and racial and ethnic differences in use and cost of public mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 34:456–464, 2007Google Scholar

4. Simpson SM, Krishnan LL, Kunik ME, et al: Racial disparities in diagnosis and treatment of depression: a literature review. Psychiatric Quarterly 78:3–14, 2007Google Scholar

5. Alegría M, Canino G, Rios R, et al: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services 53:1547–1555, 2002Google Scholar

6. Lindert J, Schouler-Ocak M, Heinz A, et al: Mental health, health care utilisation of migrants in Europe. European Psychiatry 23(suppl 1):14–20, 2008Google Scholar

7. Ghods BK, Roter DL, Ford DE, et al: Patient-physician communication in the primary care visits of African Americans and whites with depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23:600–606, 2008Google Scholar

8. Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA: Patient-physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. American Journal of Public Health 93:1713–1719, 2003Google Scholar

9. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032, 2001Google Scholar

10. Arnow BA, Blasey C, Manber R, et al: Dropouts versus completers among chronically depressed outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders 97:197–202, 2007Google Scholar

11. Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, et al: Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services 54:219–225, 2003Google Scholar

12. Verhaak PF, Hoeymans N, Garssen AA, et al: Mental health in the Dutch population and in general practice: 1987–2001. British Journal of General Practice 55:770–775, 2005Google Scholar

13. Verhaak PF, van den Brink-Muinen A, Bensing JM, et al: Demand and supply for psychological help in general practice in different European countries: access to primary mental health care in six European countries. European Journal of Public Health 14:134–140, 2004Google Scholar

14. Schene AH, Faber AM: Mental health care reform in the Netherlands. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica: Supplementum 410:74–81, 2001Google Scholar

15. Van de Ven W, Schut F: Universal mandatory health insurance in the Netherlands: a model for the United States? Health Affairs (Millwood) 27:771–781, 2008Google Scholar

16. Comino E, Silove D, Manicavasagar V, et al: Agreement in symptoms of anxiety and depression between patients and GPs: the influence of ethnicity. Family Practice 18:71–77, 2001Google Scholar

17. Bengi-Arslan L, Verhulst FC, Crijnen AA: Prevalence and determinants of minor psychiatric disorder in Turkish immigrants living in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37:118–124, 2002Google Scholar

18. Van der Wurff FB, Beekman AT, Dijkshoorn H, et al: Prevalence and risk-factors for depression in elderly Turkish and Moroccan migrants in the Netherlands. Journal of Affective Disorders 83:33–41, 2004Google Scholar

19. Levecque K, Lodewyckx I, Vranken J: Depression and generalised anxiety in the general population in Belgium: a comparison between native and immigrant groups. Journal of Affective Disorders 97:229–239, 2007Google Scholar

20. Levecque K, Lodewyckx I, Bracke P: Psychological distress, depression and generalised anxiety in Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in Belgium: a general population study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 44:188–197, 2008Google Scholar

21. de Wit MAS, Tuinebreijer WC, Dekker J, et al: Depressive and anxiety disorders in different ethnic groups: a population based study among native Dutch, and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese migrants in Amsterdam. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43:905–912, 2008Google Scholar

22. Stronks K, Ravelli AC, Reijneveld SA: Immigrants in the Netherlands: equal access for equal needs? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 55:701–707, 2001Google Scholar

23. Uiters E, Deville WL, Foets M, et al: Use of health care services by ethnic minorities in the Netherlands: do patterns differ? European Journal of Public Health 16:388–393, 2006Google Scholar

24. Carta MG, Bernal M, Hardoy MC, et al: Migration and mental health in Europe (the state of the mental health in Europe working group: appendix 1). Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health 1:13, 2005Google Scholar

25. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

26. Baarnhielm S, Ekblad S: Turkish migrant women encountering health care in Stockholm: a qualitative study of somatization and illness meaning. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 24:431–452, 2000Google Scholar

27. Stein D: Views of mental illness in Morocco: Western medicine meets the traditional symbolic. Canadian Medical Association Journal 163:1468–1470, 2000Google Scholar

28. Fassaert T, de Wit MA, Tuinebreijer WC, et al: Perceived need for mental health care among non-Western labour migrants. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 44:208–216, 2009Google Scholar

29. Hodgson RE, Lewis M, Boardman AP: Prediction of readmission to acute psychiatric units. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:304–309, 2001Google Scholar

30. Kramer TL, Miller TL, Phillips SD, et al: Quality of mental health care for depressed adolescents. American Journal of Medical Quality 23:96–104, 2008Google Scholar

31. Rossi A, Amaddeo F, Bisoffi G, et al: Dropping out of care: inappropriate terminations of contact with community-based psychiatric services. British Journal of Psychiatry 181:331–338, 2002Google Scholar

32. Wang J: Mental health treatment dropout and its correlates in a general population sample. Medical Care 45:224–229, 2007Google Scholar

33. Fortney J, Rost K, Zhang M, et al: The impact of geographic accessibility on the intensity and quality of depression treatment. Medical Care 37:884–893, 1999Google Scholar

34. Williams ME, Latta J, Conversano P: Eliminating the wait for mental health services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 35:107–114, 2008Google Scholar

35. Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, et al: Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological treatment for depression: a systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:714–719, 2004Google Scholar

36. Durbin J, Lin E, Layne C, et al: Is readmission a valid indicator of the quality of inpatient psychiatric care? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 34:137–150, 2007Google Scholar

37. Stronks K, Kulu-Glasgow I, Agyemang C: The utility of 'country of birth' for the classification of ethnic groups in health research: the Dutch experience. Ethnicity and Health 14:1–14, 2009Google Scholar

38. Peen J, Dekker J: Urbanisation as a risk indicator for psychiatric admission. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:535–538, 2003Google Scholar

39. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M: Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatric Services 50:1053–1058, 1999Google Scholar

40. Hermann RC, Leff HS, Palmer RH, et al: Quality measures for mental health care: results from a national inventory. Medical Care Research and Review 57(suppl 2):136–154, 2000Google Scholar

41. Ormel J, Koeter MW, Van Den BW, et al: Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:700–706, 1991Google Scholar

42. Smolders M: Assessing and Improving the Management of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care. Nijmegen, the Netherlands, Radboud University Nijmegen, 2009Google Scholar

43. Smolders M, Laurant M, Verhaak P, et al: Adherence to evidence-based guidelines for depression and anxiety disorders is associated with recording of the diagnosis. General Hospital Psychiatry 31:460–469, 2009Google Scholar

44. Rhodes AE, Fung K: Self-reported use of mental health services versus administrative records: care to recall? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:165–175, 2004Google Scholar

45. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61, 2001Google Scholar

46. Suurmond J, Seeleman C: Shared decision-making in an intercultural context: barriers in the interaction between physicians and immigrant patients. Patient Education and Counseling 60:253–259, 2006Google Scholar

47. Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD: Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 15:25–38, 2002Google Scholar

48. Harmsen JA, Bernsen RM, Bruijnzeels MA, et al: Patients' evaluation of quality of care in general practice: what are the cultural and linguistic barriers? Patient Education and Counseling 72:155–162, 2008Google Scholar

49. Thom DH: Physician behaviors that predict patient trust. Journal of Family Practice 50:323–328, 2001Google Scholar

50. Edlund MJ, Wang PS, Berglund PA, et al: Dropping out of mental health treatment: patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:845–851, 2002Google Scholar

51. Vega WA, Lopez SR: Priority issues in Latino mental health services research. Mental Health Services Research 3:189–200, 2001Google Scholar

52. Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ: The importance of ethnic similarity in the therapist-patient dyad among Surinamese migrants in Dutch mental health care. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 77:273–278, 2004Google Scholar

53. Mulder CL, Koopmans GT, Selten JP: Emergency psychiatry, compulsory admissions and clinical presentation among immigrants to the Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:386–391, 2006Google Scholar

54. Veling WA: Schizophrenia Among Ethnic Minorities: Social and Cultural Explanations for the Increased Incidence of Schizophrenia Among First- and Second-Generation Immigrants in the Netherlands. Rotterdam, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, 2008Google Scholar

55. De Jong JT, van Ommeren M: Mental health services in a multicultural society: interculturalization and its quality surveillance. Transcultural Psychiatry 42:437–456, 2005Google Scholar

56. Watters C: Migration and mental health care in Europe: report of a preliminary mapping exercise. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28:153–172, 2002Google Scholar

57. Fassaert T, de Wit MAS, Tuinebreijer WC: Uptake of health services for common mental disorders by first-generation Turkish and Moroccan migrants in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 9:307, 2009Google Scholar

58. Schrier AC, Theunissen JR, Kempe PT, et al: Immigrants are catching up in their access to and use of outpatient mental health services [in Dutch]. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie 47:771–777, 2005Google Scholar

59. Stockdale SE, Lagomasino IT, Siddique J, et al: Racial and ethnic disparities in detection and treatment of depression and anxiety among psychiatric and primary health care visits, 1995–2005. Medical Care 46:668–677, 2008Google Scholar