Reintegration Problems and Treatment Interests Among Iraq and Afghanistan Combat Veterans Receiving VA Medical Care

Over two million U.S. service members have been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan since America's engagement in the post-;September 11 "war on terrorism," approximately 27% of whom have been deployed more than once. Research suggests that the burden of mental disorders and symptoms, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and depression, is high among service members within the first year of returning from these deployments ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). Furthermore, with some notable exceptions ( 6 ), research suggests a rise with time since deployment in the rate of psychiatric problems among U.S. service members and veterans ( 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ), which may indicate better problem detection and more psychiatric morbidity over time. Reports of increases in marital and occupational difficulties after military service in either Iraq or Afghanistan (Iraq-Afghanistan) ( 1 , 4 , 11 , 12 ) provide further evidence of postdeployment reintegration problems.

Research on postdeployment health problems among Iraq-Afghanistan war veterans is needed to inform the development and resourcing of health services. However, the existing research base has several limitations for health services planning. First, many prevalence studies are based primarily or exclusively on samples of active-duty Army personnel and therefore do not provide information about other types of service members ( 9 ), including activated National Guard and reserve troops, who may face unique circumstances during and after their deployment ( 3 , 13 ). Second, most studies describing rates of psychiatric symptomatology have assessed service members within the year after returning from their deployment ( 1 , 3 , 5 , 8 , 14 , 15 ), leaving unexamined their long-term adjustment problems. Third, because most prior studies have focused on psychiatric disorders, we know relatively little about the functional problems that Iraq-Afghanistan veterans face as they attempt to reintegrate into their home communities. Veterans may perceive problems functioning at home, school, or work to be as important as or more important than symptom resolution ( 16 , 17 ). Last, the treatment preferences of this new generation of veterans, which differs from earlier cohorts of veterans in terms of age, education, and comfort with technology, is understudied ( 18 ).

This study was designed to address some of the above gaps in the literature. Our primary objectives were to describe the prevalence and types of community reintegration problems among Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who receive U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical care and to identify their interest in interventions or information to facilitate readjustment within the community. The VA plays a pivotal role in addressing Iraq-Afghanistan veterans' postdeployment health care needs. It provides Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who were discharged under other-than-dishonorable conditions with cost-free health care and medications for conditions possibly related to military service, regardless of their income level, for five years postdischarge ( 19 ). The VA is also the single largest provider of medical care to returning combatants.

The secondary objective of this study was to explore associations between probable PTSD, reintegration problems, and treatment interests. PTSD is of particular concern because it is the most prevalent psychiatric disorder among returning combat troops and veterans ( 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 14 , 20 , 21 , 22 ). PTSD has also been associated with functional problems among veterans of previous wars ( 23 ) and with aggressive and suicidal thoughts and behavior among Iraq-Afghanistan veterans ( 3 , 7 , 13 , 24 ). Furthermore, PTSD has a greater impact on quality-of-life outcomes than do mood and other anxiety disorders ( 25 , 26 ).

Methods

The Minneapolis VA Medical Center Subcommittee on Human Studies reviewed and approved all aspects of this research.

Sampling strategy

Our sampling frame included the 181,611 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who made at least one visit to a VA facility within the continental United States between October 2003 and July 2007. This represents 60% of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans who used VA services within this time frame. The remaining 40% were not classified as combat veterans.

We used stratified random sampling without replacement. We selected this sampling strategy to increase the precision of our estimates and models. Because sampling from demographically more homogeneous groups produces estimates with smaller error variance than a simple random sample ( 27 ), we sampled from strata that included veterans of the same race-ethnicity and gender who were living in geographically similar areas. To this end, we divided the United States into six regions (Northeast, Southeast, Upper Midwest, Southern Midwest, Northwest, and Pacific Coast). Each regional stratum was divided into four gender (male or female) and race (white or nonwhite) combinations. From each of the resulting 24 strata we randomly selected 55 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans for recruitment (N=1,320). Because one-fifth of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans had missing race-ethnicity data, we randomly selected an additional 15 men and 15 women with missing race-ethnicity information from each of the six regions (N=180). Later, we used veterans' self-report to reclassify race and ethnicity and to verify deployment. We then constructed estimates using Horvitz-Thompson type estimators, with weights equal to the inverse of sample inclusion probabilities.

Of the 1,500 veterans originally identified for survey, 274 were excluded for the following reasons: deceased (N=8), veteran of other war eras (N=89), could not be located through U.S. Postal Service after three attempts (N=167), or currently redeployed to Iraq or Afghanistan (N=10). Of the 1,226 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who remained eligible, 754 (62%) returned surveys by July 14, 2008.

Recruitment

Veterans received a prenotification letter describing the study, followed two weeks later by a cover letter, 12-page questionnaire, and $5 incentive. The cover letter reiterated the study's goals and described the risks, benefits, and voluntary nature of participation. Return of the survey signified veterans' consent to participate in the study. Nonresponders received a reminder letter and two more mailings of the questionnaire. Data were collected between April and July 2008.

VA administrative data

We used VA administrative databases to obtain the following sociodemographic information for both responders and nonresponders: age, gender, race-ethnicity, military component (active duty versus National Guard or reserve), receipt of service-related disability benefits (any benefits and benefits specifically for PTSD), use of VA mental health services within the past year (any versus none), and distance in miles to nearest VA and community-based outpatient clinics. We also extracted the past two years of the ICD-9-CM codes for PTSD, anxiety disorders other than PTSD, depression, substance use disorders (excluding nicotine dependence), psychoses, and traumatic brain injury.

Study questionnaire

The study questionnaire assessed veteran characteristics, physical and mental health, perceived community reintegration problems, and treatment interests and preferences regarding intervention service delivery (in person or over the Internet). The research team, which included clinicians with expertise in deployment-related readjustment problems and in measure development, developed the initial version of the questionnaire based on literature reviews, early findings from ongoing studies, and clinical experience. A focus group of one veteran and three active-duty service members provided the investigators with anonymous feedback on the content and format of the initial version of the survey. After incorporating this feedback, we pilot-tested the survey with a sample of 87 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans. We finalized the survey after analyzing response patterns and reviewing participant comments in the comment section.

Community reintegration and treatment preferences

One item assessed overall difficulty in readjusting to civilian life over the past 30 days on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, no difficulty, to 5, extreme difficulty. Sixteen items assessed specific problems over the past 30 days in the following functional domains: social relations, eight items; productivity, three items; community participation, two items; perceived meaning in life, one item; and self-care and leisure activities, two items. Responses ranged from 1, no difficulty, to 5, extreme difficulty. Items were modified for relevance to this population from the social relations, life activities, and self-care domains of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II ( 28 ), supplemented with content from the Community Integration Questionnaire and Community Integration Measure, which were developed for traumatic brain injury research ( 29 , 30 ). Internal consistency of these 16 items, as measured by Cronbach's coefficient alpha, was .95. Nine yes-no items were used to assess problem experiences since returning home from Iraq or Afghanistan, including four items on potentially harmful behaviors and one item each on divorce or separation, legal problems, job loss, problems accessing health care, and loss of spirituality or religious life.

To assess interest in services for readjustment problems, participants checked individual items on a list of 12 possible services. They also indicated how they would want to receive information and services for community reintegration problems. In addition, because use of the Internet has become increasingly common for health care service delivery ( 31 , 32 ), we assessed access to the Internet and frequency of Internet use.

Physical and mental health

Overall physical and mental health status was assessed with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12v2), with mental and physical health component summary scores normalized such that they could be compared with values obtained in the U.S. population, which has a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 ( 33 ). To assess probable PTSD, we used the Primary Care PTSD Screen ( 34 ), which is used by the VA and Department of Defense (DoD). A cutoff score of 3 yielded .76 sensitivity and .92 specificity for clinical PTSD in a sample of active-duty soldiers who returned from combat in Iraq ( 35 ). We screened for alcohol and drug problems using the Two-Item Conjoint Screen ( 36 , 37 ). This screen is also included in the DoD Postdeployment Health Reassessments ( 3 ). A cutoff score of 1 had .80 sensitivity and specificity among 18- to 59-year-old primary care patients ( 37 ).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence and proportions were weighted to represent the population of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who used VA medical services. We used stratified estimates weighted by the inverse of sample inclusion probabilities to calculate population parameter estimates and their standard errors ( 27 ). Less than 3% of community reintegration items had missing values. Assuming that this degree of missing data depended only on the observed covariates, we imputed missing values using logistic regression methods for multiple imputations ( 38 ). We used stratified logistic regression models to construct odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals ( 39 ) for community reintegration problems by probable PTSD status.Odds ratios were adjusted for demographic characteristics that preceded deployment, including age, gender, race-ethnicity, and military component. When comparing community reintegration problems among those with and without probable PTSD, we used a p value of <.002 as the threshold for statistical significance. Stratified Poisson regression was used to determine whether probable PTSD was associated with the number of community reintegration problems and the number of services of interest for community reintegration problems. All analyses were performed for responders and then adjusted for potential nonresponse bias based on administrative data available for both responders and nonresponders; adjustment was achieved by constructing response propensities and producing a weighted combination of within-propensity class estimates ( 40 ). SAS, version 9.2, and R coding were used to perform the calculations.

Responders did not differ from nonresponders in diagnoses extracted from VA medical records, receipt of mental health services, distance to a VA or community-based outpatient clinic, service connection for any condition, service connection for PTSD, or race-ethnicity. Compared with nonresponders, responders were older, were more likely to be female, and were more likely to have been activated to Iraq or Afghanistan from the National Guard or reserves than from active duty. The decision to adjust for demographic characteristics that preceded deployment was made a priori to increase the precision of our estimates.

Results

Participants

The median time between participants' return from their most recent Iraq or Afghanistan deployment and completion of the survey was 42 months (interquartile range 31–54 months). Roughly 22% reported more than one deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan war theaters. One-fifth of the sample had fought in prior U.S. wars. Participant and estimated population sociodemographic characteristics are listed in Table 1 . As expected, given our stratification scheme, survey respondents were roughly balanced in terms of gender and race (white or nonwhite). However, when weighted back to the overall population of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who receive VA medical care, we estimated that 87% of the population was male and 63% was white.

|

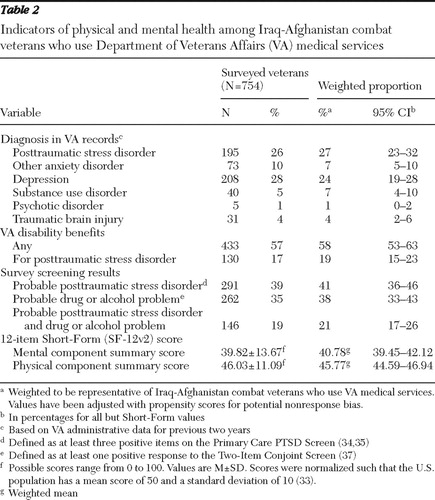

As shown in Table 2 , approximately a quarter of the population of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who had received VA medical care had a diagnosis of PTSD and 7% had a substance use disorder diagnosis documented in VA administrative records. However, on the basis of the screening measures included in our survey, we estimated that 41% and 38% of the population may have had PTSD or a drug or alcohol use problem, respectively. A total of 149 (51%) of the 291 study participants who screened positive and 46 (10%) of the 463 who screened negative for PTSD carried a PTSD diagnosis in VA medical records; 33 (13%) of the 262 who screened positive and seven (1%) of the 492 who screened negative for probable drug or alcohol use problems carried a substance use disorder diagnosis in VA medical records. The SF-12v2 scores indicated that Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans had substantially poorer overall general medical and mental health than the U.S. general population. The population majority (58%) was receiving disability benefits for a service-related condition, with PTSD being most common.

|

Reintegration problems

An estimated 40% (95% confidence interval [CI]=35%–45%) of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who used VA medical services perceived some to extreme overall difficulty in readjusting to civilian life within the past 30 days. The estimated average number of specific areas of some to extreme difficulty was 6.33±.27 out of 16. As shown in Table 3 , we estimated that at least 25% of these veterans were having some to extreme difficulty in each of the domains assessed. Difficulty in social relations (such as confiding in others and getting along with their spouses, children, and friends) were particularly common. Some to extreme productivity problems (including problems keeping a job and completing the tasks needed for home, work, or school) were reported by 25%–41% of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans. The estimated mean number of dichotomously scored problem experiences since coming home from Iraq or Afghanistan was 3.03±.12 out of nine. Potentially harmful behaviors since coming home from Iraq or Afghanistan were common, with 31% reporting more alcohol and drug use and 57% reporting more anger control problems ( Table 3 ).

|

Treatment interests

An estimated 96% (CI=93%–99%) of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who used VA medical care reported interest in services for community reintegration problems. The estimated average number of services that veterans would consider using for community reintegration problems was 6.84±.17 out of the 12 options presented. As Table 4 shows, veterans most frequently reported interest in obtaining information about VA benefits and about schooling, employment, or job training. The three most popular ways of receiving community reintegration services or information were at a VA medical center, over the Internet, and through the postal mail. Almost all Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans had access to the Internet and used it regularly.

|

Readjustment and treatment interests

Probable PTSD was associated with problem drinking or drug use and with worse SF-12v2 mental and physical component summary scores (p<.001). The odds of reporting some to extreme difficulty was significantly higher among those with probable PTSD in each functional area assessed, with odds ratios ranging from 3.10 to 13.78 ( Table 5 ). Similarly, the odds of reporting problems experienced since homecoming were higher among those with probable PTSD, with odds ratios ranging from 2.21 to 8.89 ( Table 5 ). However, functional problems and postdeployment problems were also present among those without probable PTSD. Among those with and without probable PTSD, the most commonly reported problem since homecoming was controlling anger. Finally, veterans with probable PTSD expressed interest in more types of services for community reintegration problems than those without probable PTSD (p<.001). A majority of those with probable PTSD were interested in traditional mental health services for their reintegration problems, such as face-to-face individual therapy (83%; CI=77%–89%) and medications (71%; CI=64%–79%) (data not shown).

|

Discussion

This is the first systematic study of community reintegration problems and associated treatment interests among Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who use VA medical care. More than one-half of this select population was struggling with anger control problems, and nearly one-third had engaged in behaviors that put themselves or others at risk since homecoming, such as dangerous driving and greater alcohol or drug use.

Not surprisingly, veterans with probable PTSD reported more reintegration problems and expressed interest in more kinds of services for reintegration problems than did veterans without probable PTSD. Thus this subgroup may need to be targeted more aggressively for community reintegration interventions. Regardless of PTSD status, however, Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans faced challenges in multiple domains of functioning and community involvement after deployment. Left untreated, these problems could have deleterious effects not only on the individual but also on his or her family, community, and society as a whole. We thought it hopeful that almost all of these veterans would like information or services that could help them with these problems. Because so many used the Internet frequently, Web-based applications may prove useful for delivering services and information to this newest cohort of war veterans. However, it is unknown whether treatment interest translates into treatment seeking. This is of concern because a significant proportion of individuals with common mental disorders do not seek professional help, even after they recognize the need ( 41 ). Barriers to treatment initiation include attitudes and beliefs, financial and logistical problems, system-level factors that limit access to services, and, among combat veterans, posttrauma experiences perceived as invalidating of their service ( 1 , 41 , 42 , 43 ).

Whether veterans have access to effective services to help with community reintegration problems is also uncertain. Although federal and state governments have implemented programs to promote community reintegration postdeployment, evidence of the effectiveness of these programs is lacking. Furthermore, although more than half of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans had an interest in receiving readjustment services through a VA medical facility, not all VA health care providers have the training, skills, or time to assist veterans with the broad range of problems they reported. Many of the problems that veterans endorsed, including social functioning, employment issues, anger control, and spiritual struggles, fall outside the traditional scope of medical practice. VA mental health providers, who usually have the requisite skills to address these issues, may struggle to keep up with demand. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether evidence-based treatments for PTSD would lead to satisfactory improvements in functional and readjustment outcomes. Functional outcomes are not always included in PTSD trials, and results from some trials suggest that functional improvement does not always accompany symptom reduction ( 44 ).

In contrast to the rate of PTSD diagnosis indicated in VA medical records, we identified a substantially higher rate based on responses to the Primary Care PTSD Screen (27% versus 41%, respectively). We do not know whether the medical record rate is more or less accurate than our survey screening rate. Before the post-September 11 "war on terror," PTSD was underdiagnosed in VA medical records, with provider detection of PTSD having 46.5% sensitivity and 96.6% specificity ( 45 ). Research is warranted to determine whether PTSD is underrecognized among Iraq-Afghanistan veterans, despite use of a health care system that specializes in PTSD diagnosis and treatment.

The prevalence of probable PTSD identified through our survey exceeds that obtained in surveys of active-duty Army and Marines conducted within one year postdeployment ( 1 , 14 ) and a population-based telephone survey of military personnel conducted up to five years postdeployment ( 6 ). However, prevalence of probable PTSD was lower than the rate reported in a study of veterans screened for PTSD at one VA facility using the same assessment instrument and cutoff score we used in our study ( 46 ). One would expect PTSD to be more prevalent among treatment-seeking combat veterans, many of whom have service-related disabilities, than among veterans who are not seeking treatment. Also, our study differed from prior survey studies in terms of sampling strategy, measures, measurement context (research versus clinical), and time of assessment relative to deployment, which limits comparability. A recent study that used a dynamic mathematical model combined with data from the Iraq war estimated that the rate of PTSD among Iraq war veterans will approximate 35% ( 47 ). This estimate takes into account the lag time between trauma exposure and symptom onset as well as the fact that many troops included in prevalence studies will have subsequent deployments.

There may have been important differences between survey responders and nonresponders that we were unable to identify using the VA administrative data. These unaccounted-for differences could have biased our population estimates. In addition, the study population included Iraq-Afghanistan veterans who use VA services and who were classified as combat veterans. At the time of this report, about 56% of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans were not enrolled in the VA, and of those enrolled, 40% were not classified as combat veterans. We speculate that the Iraq-Afghanistan veterans included in our sampling frame may carry a greater burden of illness than noncombatants and those who do not use the VA for health care. Because the VA is the largest single provider for returning combatants, it was important to focus our initial attention on this large and important group. However, it is unclear whether Iraq-Afghanistan veterans who receive care in the community have the same issues as those seeking VA care. Nonetheless, our findings provide a starting point for the types of issues that community providers should be alert for when treating Iraq-Afghanistan veterans.

Limitations associated with our questionnaire include use of a screening measure to identify probable PTSD rather than gold-standard diagnostic interviews. A study of Dutch Army troops found that self-report symptom measures overestimated the rate of PTSD relative to clinical interview ( 48 ). Even in cases where our screening measure identified true cases of PTSD, we do not know whether the PTSD was related to combat in Iraq or Afghanistan or to other traumatic experiences. Evidence suggests that 9%–10% of service members screen positive for PTSD before deployment to Afghanistan or Iraq ( 1 , 49 ), underscoring the need to consider predeployment mental health when drawing conclusions based on these findings. Unfortunately, information on VA disability status was of limited use for verifying deployment-related PTSD in our sample because veterans may wait years to decades before filing a claim for PTSD, if they file at all ( 50 , 51 ), and we cannot assume that all veterans in our sample had filed PTSD claims. Also, there were important areas that we did not assess in this brief mail survey, including suicidal ideation and depression. Last, it was beyond the scope of this study to address questions concerning differences in community reintegration problems according to psychiatric diagnoses other than probable PTSD, any versus no psychiatric disorder, or by number and type of medical comorbidities. Future studies should address these limitations.

On the other hand, strengths of this study include our ability to provide population-based estimates for Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who receive VA medical care and use of a rich sampling frame to adjust for potential nonresponse bias. In addition, soldiers activated from the reserves and the National Guard, who are often underrepresented in research ( 9 ), were well represented here.

Conclusions

Functional problems were common among Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who use the VA for medical care. Further, the vast majority were interested in interventions or information to help them adjust to community life. We also found that probable PTSD was closely linked to readjustment problems and to interest in treatment for these reintegration difficulties. It is unknown whether interest in treatment translates to treatment seeking for postdeployment functional problems. Veterans with community reintegration problems may face barriers to help seeking beyond the cost of medical care. For example, the stigma of mental illness has been found to be a barrier to treatment seeking among soldiers and veterans returning from combat in Iraq or Afghanistan ( 1 , 42 ). Whether people returning from these wars with PTSD symptoms and related mental health problems would be more receptive to interventions labeled as "community reintegration services" than to mental health treatments for conditions such as PTSD is an important area for future research. Our findings also underscore the need for research on innovative strategies to deliver readjustment services, including those that make use of the Internet. Overall, results from this survey point to the need for more in-depth study of the problems that Iraq-Afghanistan veterans face when adjusting to civilian life and their preferences for interventions or services to facilitate their community reintegration.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by VA grant RRP 07-315 from the U.S. Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D). The content of this article presents the findings and conclusions of the authors and does not necessarily represent the VA or HSR&D. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or manuscript preparation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 35:13–22, 2004Google Scholar

2. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS: Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295:1023–1032, 2006Google Scholar

3. Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW: Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA 298:2141–2148, 2007Google Scholar

4. Smith TC, Ryan MA, Wingard DL, et al: New onset and persistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder self reported after deployment and combat exposures: prospective population based US military cohort study. British Medical Journal 336:366–371, 2008Google Scholar

5. Lapierre CB, Schwegler AF, Labauve BJ: Posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms in soldiers returning from combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Traumatic Stress 20:933–943, 2007Google Scholar

6. Schell TL, Marshall GN: Survey of individuals previously deployed for OEF/OIF; in Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Edited by Tanielian T, Jaycox LH. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND, 2008Google Scholar

7. Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, et al: Timing of postcombat mental health assessments. Psychological Services 4:141–148, 2007Google Scholar

8. Martin CB: Routine screening and referrals for PTSD after returning from Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2005: US Armed Forces. MSMR: Medical Surveillance Monthly Report 14:2–7, 2007Google Scholar

9. Ramchand R, Karney BR, Osilla KC, et al: Prevalence of PTSD, depression, and traumatic brain injury among returning servicemembers; in Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences and Services to Assist Recovery. Edited by Tanielian T, Jaycox LH. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND, 2008Google Scholar

10. Seal KH, Metzier TJ, Gima KS, et al: Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs health care, 2002–2008. American Journal of Public Health 99:1651–1658, 2009Google Scholar

11. Mental Health Advisory Team (MHAT) V. Operation Iraqi Freedom 06-08: Iraq, Operation Enduring Freedom 8: Afghanistan. Rockville, Md, Office of the Surgeon General, Feb 14, 2008. Available at www.armymedicine.army.mil/reports/mhat/mhat_v/MHAT_V_OIFandOEF-Redacted.pdf Google Scholar

12. Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Bovin MJ, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clinical Psychology Review, in pressGoogle Scholar

13. Browne T, Hull L, Horn O, et al: Explanations for the increase in mental health problems in UK reserve forces who have served in Iraq. British Journal of Psychiatry 190:484–489, 2007Google Scholar

14. Hoge CW, Terhakopian A, Castro CA, et al: Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:150–153, 2007Google Scholar

15. Vasterling JJ, Proctor SP, Amoroso P, et al: Neuropsychological outcomes associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in women. JAMA 296:519–529, 2006Google Scholar

16. Johnson DR, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, et al: Outcome of intensive inpatient treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:771–777, 1996Google Scholar

17. Zatzick DF, Russo J, Rajotte E, et al: Strengthening the patient-provider relationship in the aftermath of physical trauma through an understanding of the nature and severity of posttraumatic concerns. Psychiatry 70:260–273, 2007Google Scholar

18. Institute of Medicine: Treatment of PTSD: An Assessment of the Evidence. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, Oct 17, 2007. Available at www.iom.edu/Reports/2007/Treatment-of-PTSD-An-Assessment-of-The-Evidence.aspx . Accessed Oct 13, 2009 Google Scholar

19. VA Healthcare Fact Sheet 16-4: Combat Veteran Eligibility. Washington, DC, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Aug 2008. www.va.gov/healtheligibility/Library/FAQs/CombatFAQ.asp#expires . Accessed Oct 13, 2009 Google Scholar

20. Dohrenwend BP, Turner JB, Turse NA, et al: The psychological risks of Vietnam for US veterans: a revisit with new data and methods. Science 313:979–982, 2006Google Scholar

21. Kang HK, Hyams KC: Mental health care needs among recent war veterans. New England Journal of Medicine 352:1289, 2005Google Scholar

22. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048–1060, 1995Google Scholar

23. Zatzick DF, Marmar CR, Weiss DS, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1690–1695, 1997Google Scholar

24. Kang HK, Bullmann TA: Risk of suicide among US veterans after returning from Iraq and Afghanistan war zones. JAMA 300:652–653, 2008Google Scholar

25. Mendlowicz MV, Stein MB: Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:669–682, 2000Google Scholar

26. Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, et al: Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:1171–1178, 2005Google Scholar

27. Cochran W: Sampling Techniques. New York, Wiley, 1977Google Scholar

28. Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHODAS II). Geneva, World Health Organization, 2000Google Scholar

29. Dijkers M: Measuring the long-term outcomes of traumatic brain injury: a review of Community Integration Questionnaire studies. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 12:74–91, 1997Google Scholar

30. McColl MA, Davies D, Carlson P, et al: The Community Integration Measure: development and preliminary validation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 82:429–434, 2001Google Scholar

31. Jones JB, Snyder CF, Wu AW: Issues in the design of Internet-based systems for collecting patient-reported outcomes. Quality of Life Research 16:1407–1417, 2007Google Scholar

32. Ritterband LM, Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, et al: Internet interventions: in review, in use, and into the future. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 34:527–534, 2003Google Scholar

33. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al: Quality Metric Health Outcomes Solutions: User's Manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI, Quality Metric, 2007Google Scholar

34. Prins A, Ouimette PC, Kimerling R, et al: The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry 9:9–14, 2004Google Scholar

35. Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, et al: Validating the Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist with soldiers returning from combat. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 76:272–281, 2008Google Scholar

36. Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, et al: Post-Deployment Psychological Screening: Interpreting DD2900. Heidelberg, Germany, US Army Medical Research Unit-Europe, 2005Google Scholar

37. Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, et al: A two-item conjoint screen for alcohol and other drug problems. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 14:95–106, 2001Google Scholar

38. Little RJA, Rubin DB: Statistical Analysis With Missing Data, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 2002Google Scholar

39. Morel JG: Logistic regression under complex survey designs. Survey Methodology 15:203–223, 1989Google Scholar

40. Little RJA: Survey nonresponse adjustments for estimates of means. International Statistical Review 54:139–157, 1986Google Scholar

41. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84, 2002Google Scholar

42. Sayer NA, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Spoont M, et al: A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 72:238–255Google Scholar

43. Burnam MA, Meredith LS, Helmus TC, et al: Systems of care: challenges and opportunities to improve access to high quality care; in Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences and Services to Assist Recovery. Edited by Tanielian T, Jaycox LH. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND, 2008Google Scholar

44. Sayer NA, Carlson K, Schnurr P: Assessment of functioning and disability in individuals with PTSD; in Clinical Manual for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Edited by Benedek D, Wynn GH. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc, in pressGoogle Scholar

45. Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, et al: Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. General Hospital Psychiatry 27:169–179, 2005Google Scholar

46. Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, et al: Getting beyond "Don't ask: don't tell": an evaluation of US Veterans Administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Public Health 98:714–720, 2008Google Scholar

47. Atkinson MP, Guetz A, Wein LM: A dynamic model for posttraumatic stress disorder among US troops in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Management Science 55:1454–1468, 2009Google Scholar

48. Engelhard IM, van den Hout MA, Weerts J, et al: Deployment-related stress and trauma in Dutch soldiers returning from Iraq: prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry 191:140–145, 2007Google Scholar

49. Brailey K, Vasterling JJ, Proctor SP, et al:PTSD symptoms, life events, and unit cohesion in US soldiers:baseline findings from the Neurocognition Deployment Health Study. Journal ofTraumatic Stress 20:495–503, 2007Google Scholar

50. Sayer NA, Murdoch M, Carlson KF: Compensation and PTSD: consequences for symptoms and treatment. PTSD Research Quarterly 18:1–8, 2007Google Scholar

51. Murdoch M, Nelson DB, Fortier L: Time, gender, and regional trends in the application for service-related post-traumatic stress disorder disability benefits, 1980–1998. Military Medicine 168:662–670, 2003Google Scholar