Enhancing "Usual Practice" Treatment Foster Care: Findings From a Randomized Trial on Improving Youths' Outcomes

For the past 30 years, the field of children's mental health has undergone a number of paradigmatic changes. Beginning in the late 1970s, the focus was on addressing the conspicuous gaps and problems in the overall systems that served children with mental health problems ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Enthusiasm about developing and expanding systems of care was challenged with a series of findings in the final years of the 20th century showing that although it was possible to improve systems, it was not clear that such improvements led to increased benefit for children and families ( 4 , 5 ). This contentious period led to a new focus in which systems came to be viewed as potentially necessary but not sufficient to bring about desired individual-level outcomes. This led, in turn, to a heightened interest in understanding the "black box" of treatment. Currently, near the end of the first decade in the 21st century, this emphasis on evidence-based practice has become the new rallying cry.

Within the literature on children's mental health, there has been a growing recognition that these paradigms and trends should be brought together: for the most difficult-to-treat youths, significant improvements in outcomes are likely to require practice-level changes that involve provision of effective treatments and supports within the framework created by systems of care ( 6 , 7 ). Much of the current effort (within systems of care and beyond) focuses on how to develop, evaluate, and disseminate evidence-based treatment. Although this emphasis on treatments' ability to create desired change is critical to the field, it also has the potential to focus on a small number of treatments in relatively few settings and to thereby limit our thinking and recognition about the range of services, treatments, and systems that serve the vast majority of U.S. children with serious emotional disturbance and their families.

Treatment foster care (TFC), one of the few community-based treatment options for youths for which there is a substantial evidence base ( 8 , 9 , 10 ), has thrived in this shifting environment. It is appealing from a system-of-care perspective because it provides least-restrictive residential treatment, allows for family-based living and community-based opportunities for learning and development, and is individualized to address a child's strengths and needs. Chamberlain and colleagues ( 8 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) have done a series of studies to develop the evidence base and have carefully described the model in ways that make it replicable by others. The evidence-based model, multidimensional treatment foster care (MTFC), was developed in Oregon and is being disseminated in over 50 sites in the United States and other countries. Although this is tremendously promising, there are at least 2,000 programs that provide TFC across the United States. So, as with most treatment approaches, the vast majority of agencies providing TFC are not providing the evidence-based version ( 14 ).

Interviews with directors of TFC agencies in a statewide sample suggest that there are both practical and philosophical reasons that agencies do not see the current evidence-based model as viable for them (for example, lack of resources to hire required staff; opposition to the use of point charts in homes; and use of contract, rather than in-house, clinicians). But most directors expressed a desire to improve quality and outcomes in their TFC programs. Quantitative data from these same surveys show that there is certainly a need to improve practice in "usual care" TFC agencies ( 15 ).

This article reports on a randomized trial that attempted to enhance TFC in these usual care settings by drawing from evidence-based practice and well-established treatment approaches and by building on evidence from research about what works in existing usual care TFC programs ( 16 , 17 , 18 ). The study was designed to evaluate the effect of increased training and consultation for TFC supervisors and treatment parents (also referred to as treatment foster parents) in an effort to change practice and improve youth-level outcomes.

Methods

Overall design and sample

The study was a randomized trial of TFC agencies in a southeastern state. It was conducted in 2003–2008. Random assignment was done at the agency level: seven agencies were in the intervention group (enhanced TFC), and the other seven were in the control group (usual care TFC). Agencies randomly assigned to the intervention arm received study-provided training and consultation. Agencies in the control arm continued to provide training and services as usual. All youths served by these agencies during the 18-month recruitment period were eligible for inclusion in the study. Overall, 247 youths and their treatment parents participated. [A figure showing the number of persons recruited and enrolled for the study is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] Data were collected at baseline, six months, and 12 months from treatment parents and youths. Results presented here reflect an intent-to-treat approach, with all participating youths included in analyses.

Sample characteristics

A prior statewide study of TFC provided a list of agencies, from which a subset was selected for the randomized controlled trial ( 15 , 19 ). The resulting sample included programs distributed throughout the state. Two of the programs were operated by public mental health authorities (one was randomly assigned to each study arm), and the others were privately managed. Overall, programs had been operating from two to 15 years and had 13 to 50 licensed homes at baseline. The sample included youths who lived in TFC homes in participating agencies at the time the study started as well as all youths who entered the agencies during the following 18 months.

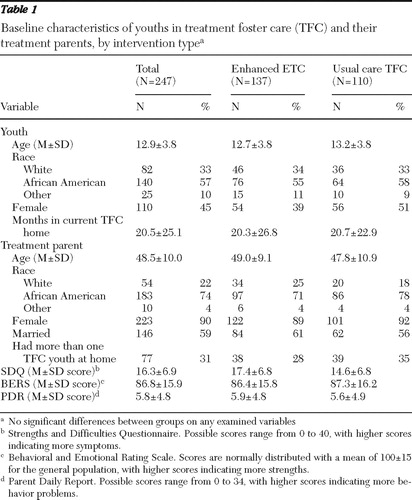

Youths in the intervention and control conditions were comparable on a range of domains. As shown in Table 1 , they had an average age of approximately 13 years (range, two to 21 years at baseline), approximately half were female, and two-thirds were from minority racial-ethnic groups. At baseline, youths had been living in their current TFC home for an average of 20 months (with a range of less than one month to over 12 years).

|

Treatment parents in the two conditions were also similar ( Table 1 ). The majority were female and from minority racial-ethnic groups (mostly African American). In nearly one-third of homes, there was more than one TFC youth placed at the time of the baseline interview.

The analyses presented here used an intent-to-treat approach, so that all available data were used to assess outcomes, regardless of the amount of time that youths were in the TFC program. It should be noted that a substantial portion of youths moved between TFC homes or were discharged during the 12-month follow-up. Of the 192 children who remained in the sample through 12 months, by six months, 142 (74%) remained in TFC (126, or 66%, lived in the same TFC home where they were recruited for the study), and by 12 months, 117 (61%) remained in TFC (90, or 47%, in the same home). Rates of movement or discharge were not significantly different in the two study arms.

Intervention

Enhanced TFC was developed by bringing together data from our previous statewide descriptive study of TFC with elements of Chamberlain's evidence-based MTFC. Many of the components that are considered to be critical to TFC were already evident in usual care practice. These included care coordination, a view of treatment parents as key change agents, a team approach to treatment, respite, and work with youths' families. However, compared with the evidence-based version of TFC, usual care TFC was conspicuously lacking in several areas: intensity of supervision and support of treatment parents by TFC supervisory staff and proactive teaching-oriented approaches to problem behaviors. Therefore, the study provided training to the intervention group on these potentially critical areas.

Training with TFC supervisors and treatment parents followed a study-developed protocol titled Together Facing the Challenge ( 20 , 21 ). This train-the-trainer model included two full days of training with TFC supervisors before training with treatment parents. The two-day training with supervisors provided an overview of the upcoming training to be done with treatment parents, discussion about their current practices and interactions with treatment parents, and opportunities to practice skills and training elements so that they could serve as cofacilitators in the training for treatment parents. Follow-up consultation visits with supervisors were held monthly for one year after this initial training. These group-format consultation sessions focused on a combination of preplanned topics as well as discussion and problem solving of emergent and salient issues from the supervisors.

Training with treatment parents was conducted over a six-week period, with 2.5-hour sessions once a week (sessions were held in the evening, and a meal and childcare were provided). All training sessions were led by the study's intervention director, with assistance from agency TFC supervisors. Topics for the six weeks included building relationships and teaching cooperation, setting expectations, using effective parenting tools to enhance cooperation, implementing effective consequences, preparing youths for the future, and taking care of self. All sessions included didactic instruction, role plays and exercises, and homework assignments for the treatment parent to do during the week ( 21 ).

Much of the training built on established parent-training approaches found in MTFC. In addition, two additional elements emerged from our previous study of usual care TFC and were included in the intervention. In contrast to the relatively short-term focus of MTFC, nearly half of the youths in our previous study were in TFC for over two years ( 15 , 19 ). With these extended stays, two issues emerged that were not formally addressed in MTFC or in existing treatment-as-usual TFC: preparation for adulthood and previous trauma. Therefore, focus on transition-related issues was included in the training and consulting work with supervisors. Previous trauma was addressed via training and consultation with local clinicians who worked with youths from the participating TFC programs in trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy ( 22 ). The study provided a cadre of trained clinicians in each participating community. Whether a specific youth received such treatment was decided by agencies and clinicians on an individual basis.

Data

Data were from in-person interviews with treatment parents at baseline, six months, and 12 months. Primary variables for the analyses focused on youth-level outcomes. These include scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) ( 23 ), Parent Daily Report (PDR) ( 24 ), and the Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale (BERS) ( 25 ). All three of these measures have been used previously in research on youths with emotional and behavioral problems and have acceptable psychometric properties.

The SDQ provides an indication of clinical severity of the youth's problems. This 25-item measure includes five subscales (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, inattention-hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior) as well as a total difficulties score (composed of the first four subscales) ( 26 ). Analyses presented here used the total difficulties score. Possible scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating more problems.

The PDR obtains information about the number of types of problematic behavior the youth displayed in the past 24 hours. It has been used in previous studies of youths in TFC and foster care to examine patterns of problem behavior over time ( 27 ). In MTFC (Chamberlain's evidence-based model), the PDR is also used for daily data collection and feedback on behaviors to inform treatment ( 9 ). The PDR was not used in this latter way in the study presented here. Rather, it served only as a data collection instrument by the research staff at each follow-up interval. Possible scores range from 0 to 34, with higher scores indicating more problems.

The BERS provides an indication of a youth's strengths ( 25 ). This 52-item instrument includes five subscales (interpersonal strength, family involvement, intrapersonal strength, school functioning, and affective strength) and an overall strength quotient, which was used in the analyses presented here. The BERS strength quotient is a standardized scale with a mean±SD of 100±15 in the general population.

Written informed consent was obtained from each youth's parent or legal guardian for the youth's inclusion in the study. Written consent was obtained from each participating treatment parent before interviews.

Data analysis

The study included 247 youths who were in agencies randomly assigned to one of two groups: enhanced TFC (N=137) or usual care TFC (N=110). To establish the validity of the randomization, baseline characteristics of participants in the two study arms were compared on a variety of dimensions. As noted in Table 1 , there were no significant differences between groups on the range of included factors. There were also no significant relationships between randomization or baseline characteristics and attrition. Analyses were based on the intent-to-treat sample using full likelihood methods. Such methods provide valid estimates and inferences with incomplete data when assumptions of ignorability are satisfied.

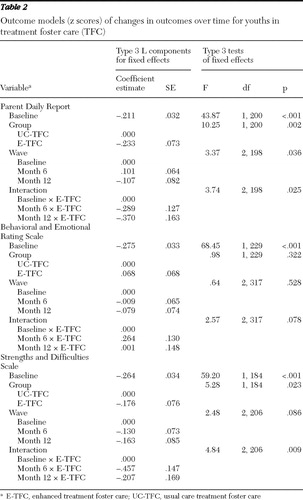

Each focal outcome (PDR, BERS, and SDQ) was centered on the mean and standardized to facilitate comparisons between measures ( 28 ). The difference in z scores between baseline and follow-up formed the primary outcome measure. Therefore, results represent mean-centered changes in standard deviation (that is, z score) units.

By using repeated-measures linear regression procedures (SAS, Proc Mixed), each outcome was regressed on a model that included wave (as a class variable), a dichotomous proxy variable denoting randomization status, and an interaction term crossing these two. In addition, the baseline z score for the focal outcome was included to control for differences among baseline levels of the relevant outcome measure. Covariance structure was specified as first-order autoregressive on the basis of inspection and a comparison of -2 log likelihood values for competing covariance structures. Post hoc contrasts between the differenced z scores across the two study arms were estimated at six and 12 months after adjustment to control for multiple comparisons ( 29 ).

Because the wave and group were entered categorically, results were based on type 3 tests. Therefore, we present type 3 components for each level of wave and group as derived from the L matrix of contrasts as well as an F test evaluating the overall significance of each effect. Type 3 tests are generally considered superior to type 1 and type 2 tests and are particularly useful in models with categorical interaction terms where effects are distributed over multiple measures ( 30 ). The interaction term, representing the differential rate of change in the mean-centered standardized outcome measures from baseline to 12 months among youths randomly assigned to the enhanced TFC condition, provides the primary test of the study hypotheses.

Results

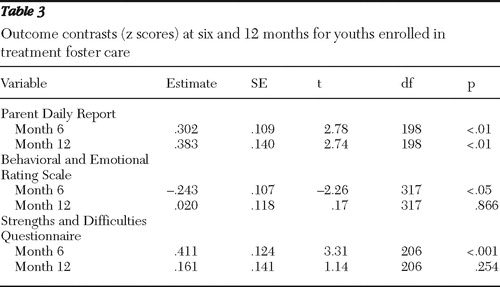

A comparison of the outcomes for the two groups is presented in Tables 2 and 3 . For all three examined outcomes, there was a significant difference between the two groups in the rate of change. In each instance, youths in the intervention group showed improvements across time. In contrast, youths in the control group remained relatively stable (or showed minor worsening) across time. Significant wave-by-group interaction terms for the PDR and SDQ measures show that rates of change were significantly greater among youths in the intervention group than among those in the control group. The wave-by-group interaction for the BERS approached significance (p<.078).

|

|

Figure 1 depicts these changes over time. The effects were strongest and most sustained for the PDR measure. In the enhanced TFC arm, rates of problem behaviors as measured by the PDR decreased across time, and the difference between the two groups was significant at both six and 12 months. Youths in the control group showed slight increases in problem behaviors by six months that subsequently remained constant. The SDQ measure also showed that youths in the enhanced TFC condition were markedly improved by six months. However, by 12 months, the difference was not statistically significant. The BERS measure showed the smallest difference between groups. Youths in enhanced TFC showed small improvements in strengths during the first six months (p<.05), but by 12 months, the two groups were no longer significantly different.

Units in the above analyses are expressed as z scores. Converting these back to the units of the focal variables provides a more intuitive and concrete view of the effects. For the PDR, for example, these results suggest that a youth in the intervention group who had a mean level of problems at baseline (PDR score of 5.9) would have, on average, a PDR score of 4.2 at six months and a score of 3.8 at 12 months. Similarly, movement on the SDQ would go from a mean score of 17.4 at baseline, to 14.3 at six months, and 16.0 at 12 months. As indicated above, the amount of change was smallest for the BERS: from 86.4 at baseline, to 91.0 at six months, back to 86.4 at 12 months.

These findings suggest that the observed changes were not strictly linear, suggesting that a quadratic model might be more appropriate. To test this, all models were reestimated after adding a quadratic term for time, including its interaction with group. In no instance was model fit significantly improved by the addition of the quadratic term (results not shown), suggesting that a linear fit, although not perfect, was adequate.

Discussion

This article reports on the initial youth-level outcomes of a randomized trial of enhanced TFC. This study is the first of its kind to examine the effects of increased training and consultation for supervisors and treatment parents in usual care TFC agencies. On the three focal outcomes—symptoms, problem behaviors, and strengths—the enhanced model showed significant improvements over usual care TFC, particularly at six months, when most youth were still in TFC.

This study used a somewhat different approach to addressing change than has been done in much of the dissemination research in children's mental health. Together Facing the Challenge built upon two sources of input—elements from evidence-based practice and data from what was working in existing TFC agencies. This hybrid model was designed to infuse existing agencies with improved practices that had been shown in randomized trials and observational study to be associated with better outcomes for youths. It attempted to recognize the resource limitations and philosophical orientations of existing agencies, while providing increased training and support in critical areas. The study focused on programs that were representative of existing statewide agencies, rather than on agencies that had resources or incentives to initiate the change process. Therefore, it moves beyond the early adopters ( 31 ) to examine potential for change across the range of existing programs. The approach and findings presented here apply only to TFC. However, it may be useful to assess whether such a hybrid approach may have implications for improving usual care in other interventions.

Although these results are promising, it should be recognized that the level of change seen in any individual outcome is in the small to moderate range. The preponderance of evidence across multiple outcomes—all in favor of the intervention group—bolsters support for the intervention. Additional work is needed to fully understand the decrease in effects of the intervention by 12 months for two of the outcomes. At this point, it is not clear whether this reflects a true diminishing of the effect postintervention or a lack of uptake to sustain the intervention beyond the study-driven training phase or that the intent-to-treat design is diluting effects for specific subgroups (for example, youths who remained in TFC throughout the study period, youths successfully discharged, and youths who received different sets of other services). Additional analyses are needed to examine processes and key factors that underlie these intent-to-treat findings (for example, quality of implementation and receipt of additional services beyond TFC).

Conclusions

These results suggest the positive potential of this hybrid approach to improving outcomes in a wide range of TFC agencies. At this point, much more analysis is necessary to understand the processes by which these changes were created and to examine whether there are subgroups (of agencies, families, or youths) for whom the intervention was particularly successful. Such analyses will help identify potential causal mechanisms, the importance of the various intervention components, and, hopefully, targeted subgroups for future work. Such work should lead to improved knowledge of what works across a broad range of agencies and programs to elevate the overall practice and outcomes for youths in community-based residential placements.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant MH057448 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Behar L: Changing patterns of state responsibility: a case study of North Carolina. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 14:188–195, 1985Google Scholar

2. Knitzer J: Unclaimed Children: The Failure of Public Responsibility to Children and Adolescents in Need of Mental Health Services. Washington, DC, Children's Defense Fund, 1982Google Scholar

3. Stroul B, Friedman R: A System of Care for Children and Youth With Severe Emotional Disturbances. Washington, DC, Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center, 1986Google Scholar

4. Bickman L, Guthrie PR, Foster EM, et al: Evaluating Managed Mental Health Services: The Fort Bragg Experiment. New York, Plenum, 1995Google Scholar

5. Burns BJ, Farmer EMZ, Angold A, et al: A randomized trial of case management for youths with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 25:476–486, 1996Google Scholar

6. Rosenblatt A: Assessing the child and family outcomes of systems of care for youth with serious emotional disturbance; in Outcomes for Children and Youth With Behavioral and Emotional Disorders and Their Families. Edited by Epstein M, Kutash K, Duchnowski A. Austin, Tex, Pro-Ed, 1998Google Scholar

7. Stroul B, Blau G, Sondheimer D: Systems of care: a strategy to transform children's mental health care; in The System of Care Handbook: Transforming Mental Health Services for Children, Youth and Families. Edited by Stroul B, Blau G. Baltimore, Brookes, 2008Google Scholar

8. Chamberlain P: Family Connections: A Treatment Foster Care Model for Adolescents With Delinquency. Eugene, Ore, Castalia, 1994Google Scholar

9. Chamberlain P: Treatment foster care; in Community Treatment for Youth: Evidence-Based Interventions for Severe Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Edited by Burns B, Hoagwood K. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002Google Scholar

10. Chamberlain P, Mihalic S: Blueprints for Violence Prevention, Book Eight: Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care. Boulder, Colo, Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence, 1998Google Scholar

11. Chamberlain P, Leve LD, DeGarmo DS: Multidimensional treatment foster care for girls in the juvenile justice system: 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 75:187–193, 2007Google Scholar

12. Eddy JM, Chamberlain P: Family management and deviant peer association as mediators of the impact of treatment condition on youth antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:857–863, 2000Google Scholar

13. Eddy JM, Whaley RB, Chamberlain P: The prevention of violent behavior by chronic and serious male juvenile offenders: a 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 12:2–8, 2004Google Scholar

14. Rones M, Hoagwood K: School-based mental health services: a research review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 3:223–241, 2000Google Scholar

15. Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Dubs MS, et al: Assessing conformity to standards for treatment foster care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 10:213–222, 2002Google Scholar

16. Horn SD, Gassaway J: Practice-based evidence study design for comparative effectiveness research. Medical Care 45:50–57, 2007Google Scholar

17. Manderscheid RW: Some thoughts on the relationships between evidence based practices, practice based evidence, outcomes, and performance measures. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33:646–647, 2006Google Scholar

18. Schiffman J, Dovkervoet CM: Improving services through evidence-based practice elements; in The System of Care Handbook: Transforming Mental Health Services for Children, Youth and Families. Edited by Stroul B, Blau G. Baltimore, Brookes, 2008Google Scholar

19. Farmer EMZ, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, et al: Treatment foster care in a system of care: sequences and correlates of residential placement. Journal of Child and Family Studies 12:11–25, 2003Google Scholar

20. Murray M, Dorsey S, Farmer EMZ, et al: Together Facing the Challenge: A Therapeutic Foster Care Resource Toolkit. Durham, NC, Duke University, 2005Google Scholar

21. Murray M, Farmer EMZ, Southerland D, et al: Enhancing and adapting treatment foster care: lessons learned in trying to change practice. Journal of Child and Family Studies, in pressGoogle Scholar

22. Deblinger E, Heflin AH: Treating Sexually Abused Children and Their Nonoffending Parents: A Cognitive Behavioral Approach. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1996Google Scholar

23. Goodman R, Scott S: Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 27:17–24, 1999Google Scholar

24. Chamberlain P, Reid JB: Parent observation and report of child symptoms. Behavioral Assessment 9:97–109, 1987Google Scholar

25. Epstein MH, Sharma J: Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale: A Strength-Based Approach to Assessment. Austin, Tex, Pro-Ed, 1998Google Scholar

26. Bourdon KH, Goodman R, Rae DS, et al: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: US normative data and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:557–564, 2005Google Scholar

27. Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve LD, et al: Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science 9:17–27, 2008Google Scholar

28. Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, et al: Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 2003Google Scholar

29. Hochberg Y: A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 75:800–802, 1988Google Scholar

30. Searle SR: Linear Models. New York, Wiley, 1971Google Scholar

31. Rogers EM: Diffusion of Innovations. New York, Free Press, 1995Google Scholar