Characteristics of Patients With Bipolar Disorder Managed in VA Primary Care or Specialty Mental Health Care Settings

Bipolar disorders (types I and II) are chronic conditions that affect up to 5.5% of the general population ( 1 ) and are associated with substantial functional impairment ( 2 ) and economic loss ( 3 ). In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) over 60,000 persons were diagnosed as having bipolar disorder in fiscal year (FY) 2000, and that number increased 25% by FY 2006 ( 4 ). In contrast to other serious mental illnesses, bipolar disorder is uniquely characterized by alternating periods of manic, depressive, mixed, or euthymic episodes, leading to variations in psychosocial functioning over time ( 5 ). Patients with bipolar disorder also incur the most health care costs of those with any mental illness ( 6 , 7 ). Up to 70% of these costs occur in non-mental health settings ( 7 , 8 ).

Patients with bipolar disorder are more likely than those with schizophrenia to be diagnosed as having co-occurring general medical conditions ( 9 ). Yet the failure of individuals with serious mental illnesses, such as bipolar disorder, to receive appropriate medical care contributes to 15 to 25 years premature mortality ( 10 , 11 ). Hence, continuity of general medical care is vital for this group ( 12 , 13 ).

Little is known about the extent to which patients with bipolar disorder rely on general medical (primary) care as opposed to mental health care. Specialty mental health clinics have been the traditional health care setting for treating persons with serious mental illnesses ( 14 , 15 ). However, recent data suggest that over one-third of second-generation antipsychotic medications are prescribed exclusively by primary care providers in privately insured health plans ( 16 , 17 ). These medications, often used as antimanics or mood stabilizers in bipolar disorder, may also have medical consequences, such as diabetes and obesity ( 18 , 19 ). Some VA patients with mood disorders prefer to be seen in primary care because of the stigma of a psychiatric diagnosis. Primary care is also the de facto source of care for persons with affective disorders because of limited access to mental health services, even in the VA ( 20 , 21 ). The substantial prevalence of medical comorbidity and the wide range of functioning experienced by persons with bipolar disorder suggest the need for a more active role of general medical providers ( 22 , 23 ). Understanding how patients with bipolar disorder who use primary care exclusively differ clinically from those with access to mental health specialty services can inform the creation of effective, efficient, and patient-centered systems of care for this group.

The purpose of this study was to compare the clinical characteristics, use of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy, and outcomes of patients diagnosed as having bipolar disorder who were exclusively seen in VA primary care settings with those of patients with bipolar disorder who received any VA mental health services. We hypothesized that persons with bipolar disorder who used primary care services exclusively would be less likely to receive antimanic medications that are recommended in clinical practice guidelines and more likely to have poor general medical outcomes (defined as medical hospitalizations, comorbidity, and low physical health-related quality-of-life scores).

Methods

VA patients who completed the 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees (LHSV) and were diagnosed as having bipolar disorder in 1998–1999 were included in this study. Administered in 1999, the LHSV is the largest survey ever conducted of veterans using VA health services, and it is one of the largest comprehensive assessments of health status, sociodemographic characteristics, behaviors, and utilization within a national patient population ( 24 ). The reliability and validity of the LHSV survey questions have been reported elsewhere ( 25 , 26 ).

Study population

Data from the LHSV were linked to the VA's National Psychosis Registry (NPR) ( 4 ). The NPR was used to identify patients with an ICD-9 diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The NPR includes administrative data on utilization, pharmacotherapy, and comorbidities linked to LHSV data for those diagnosed as having bipolar disorder.

Patients were included if they had any primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder in 1998–1999. No other co-occurring diagnoses (for example, anxiety or substance use disorders) were used as criteria for exclusion. Patients with bipolar disorder (type I or II) were identified with the NPR by using the following ICD-9 codes: 296.0–296.1 and 296.4–296.8, with 296.89 the defining ICD-9 code for bipolar II disorder. On the basis of previously established methods ( 4 ), we classified patients as having bipolar disorder according to the most frequently occurring diagnosis in 1999. This study received approval from the local institutional review board at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, and informed consent from patients was not required for this secondary data analysis.

Data from electronic records

LHSV survey data on patient, clinical, and behavioral factors were linked to VA electronic medical record data on utilization in 1999, including pharmacotherapy and inpatient use. Additional data, including age (as of LHSV survey date), gender, service-connected disability, and co-occurring general medical and psychiatric conditions were available from VA electronic medical record data.

Primary care use

Patients exclusively using primary care services in 1999 were identified using VA outpatient codes for primary (that is, general medical) care services. Patients were categorized separately if they received care in VA mental health specialty settings (that is, using any mental health specialty services in 1999 with or without primary care use). Sensitivity analyses that compared those who used mental health care exclusively (no use of primary care) with those who used primary care exclusively yielded similar outcomes.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes included medical and psychiatric hospitalizations, physical and mental health-related quality of life, and guideline-concordant antimanic medication use. Inpatient medical or psychiatric visits were ascertained from 1999 VA administrative data and defined using VA bed section codes at the time of discharge and represent the primary reason for hospitalization. Health-related quality of life was measured with the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) from the LHSV ( 27 ), which generates a mental component score (MCS) and physical component score (PCS). Possible scores for each subscale range from 0, worst possible health, to 100, best possible health, with a general population mean±SD score of 50±10.

Guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy was defined as a prescription for an antimanic medication occurring from the date of the index bipolar disorder diagnosis up to 12 months later for persons who had bipolar I disorder. Pharmacy data were ascertained from the VA pharmacy benefits management database and linked with our LHSV sample. Because we focused on antimanic medications, we limited analysis of guideline-concordant care to persons with bipolar I disorder ( 28 , 29 ). Antimanic medications included lithium, divalproex, valproic acid, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. Because second-generation antipsychotic medications may also be considered recommended treatments for acute mania, a second version of this indicator was created to include these medications (olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and clozapine) along with the antimanic medications listed above. These indicators represented guideline-concordant antimanic medication use for bipolar disorder that have been in place and virtually unchanged since 1995 ( 28 ).

Covariates

Using the LHSV and administrative data, we examined available patient sociodemographic and clinical and severity factors thought to influence the association between services received exclusively in primary care and outcomes and guideline-concordant psychopharmacology. From the LHSV we ascertained self-reported patient race and ethnicity, education, and marital status. Current employment status was also ascertained, and categories included employed, unemployed, homemaker or student, retired, or disabled status (which is defined as unable to work). Additional patient factors from the LHSV included support (having someone to take you to the doctor and living alone or not), financial hardship (defined as not having sufficient money to buy food), any VA service connection (defined as whether the patient receives free care for an illness or injury received during time in military service), and any non-VA services use compared with sole reliance on VA care. Non-VA services use is a proxy for access to additional medical services outside the VA. Whether patients lived in rural versus urban settings was also included.

For clinical and severity factors, data on co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions were ascertained from VA electronic data. Using ICD-9 codes from VA administrative data, we assessed whether the patient had a diagnosis in 1999 of one of the following common general medical conditions: diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or cerebrovascular disease. We focused on these conditions because they represent the most common general medical conditions seen among patients with bipolar disorder and because they represent cardiometabolic risk factors that are most strongly associated with mortality ( 9 , 10 ). We also assessed the burden of other general medical comorbidities using the Charlson Comorbidity Index for administrative data ( 30 ) modified to exclude the aforementioned conditions. Psychiatric conditions were gathered from VA administrative data and included dementia, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and illicit drug use. Alcohol use disorder was estimated from the LHSV survey with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test question on hazardous (binge) drinking ( 31 ). Current smoking was ascertained from the LHSV survey.

Statistical analyses

Bivariate analyses were used to determine patient characteristics associated with exclusive primary care use in 1999. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to determine the association between exclusive primary care use, guideline-concordant care, and probability of an inpatient medical or psychiatric visit, controlling for patient demographic and clinical factors (for example, any non-VA utilization). In the multivariable analyses, age and score on the Charlson Comorbidity Index were categorized, because both variables were nonnormally distributed. Multivariable linear regression analyses were used to assess the association between exclusive primary care use and quality of life (SF-36 PCS and MCS scores).

Results

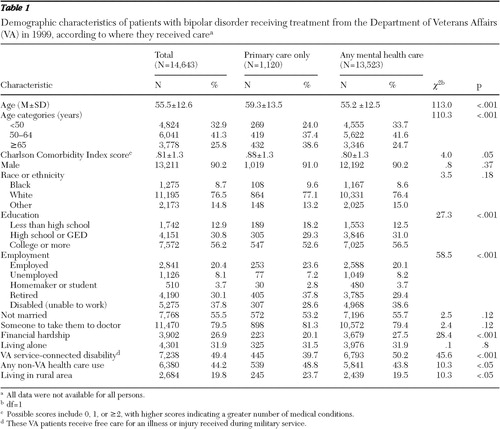

Out of 14,643 individuals diagnosed as having bipolar disorder, 1,120 (7.6%) used primary (general medical) services exclusively. The mean age of the entire sample was 55.5 years, 90.2% were male, and 76.5% were white. Table 1 shows demographic information of the total sample and the two subgroups.

|

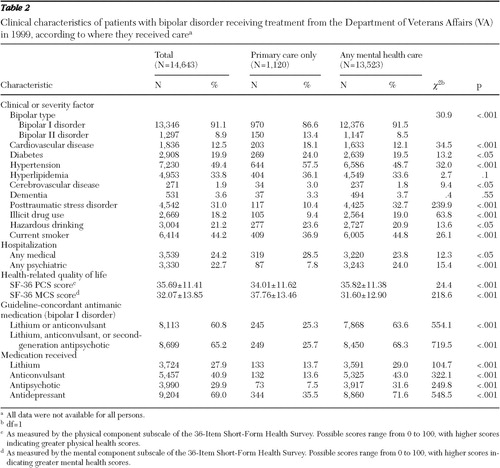

Table 2 shows clinical factors, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life. Compared with patients using any mental health care, those who used primary care exclusively were more likely to be diagnosed as having a general medical condition, notably cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or diabetes, and were more likely to be hospitalized for a medical condition. However, persons who used primary care exclusively were less likely to be diagnosed as having co-occurring PTSD or substance use disorder. Bivariate analyses also revealed that persons who used any mental health services were more likely than those who used primary care exclusively to receive any mood stabilizers (68.3% versus 25.7%). For the entire sample, scores on the PCS averaged 35.7 and scores on the MCS averaged 32.1, and persons who received only primary care were significantly more likely to have higher MCS scores and lower PCS scores ( Table 2 ).

|

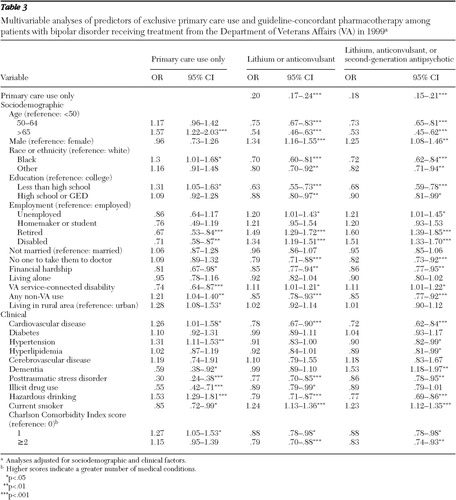

Multivariable results regarding exclusive primary care use and utilization of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy are presented in Table 3 . After the analysis controlled for sociodemographic and clinical factors (severity of illness, including co-occurring general medical and psychiatric conditions), persons who used primary care exclusively were more likely than those who did not to be diagnosed as having cardiovascular disease (odds ratio [OR]=1.26, p<.05) and hypertension (OR=1.31, df=30, p<.01) and were more likely to have a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 1 (possible scores are categorized as 0, 1, and ≥2, with a higher score indicating greater comorbidity) (OR=1.27, p<.05) ( Table 3 ). Persons who used primary care exclusively were less likely to be diagnosed with co-occurring psychiatric conditions, including dementia (OR=.59, p<.05) and PTSD (OR=.30, p<.001), and less likely to use illicit drugs (OR=.55, p<.001), yet they were more likely to self-report hazardous drinking (OR=1.53, p<.001). After the analysis adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical factors, patients with bipolar I disorder who exclusively used primary care were still less likely to receive any mood stabilizers (OR=.18, p<.001) ( Table 3 ).

|

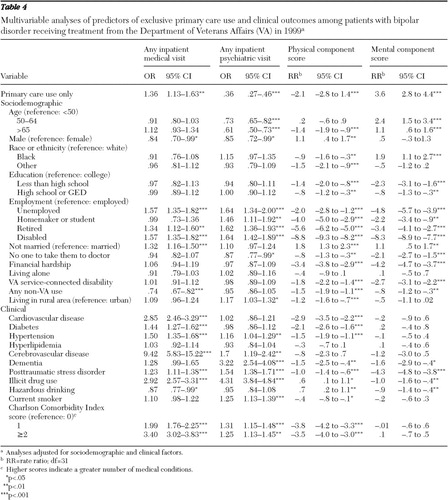

Table 4 presents results for outcomes including hospitalizations and health-related quality of life. Adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical factors revealed that persons who used primary care exclusively were more likely than those using any mental health services to have an inpatient medical hospitalization (OR=1.36, p<.01) and less likely to have a inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (OR=.36, p<.001) ( Table 4 ). Compared with those who did not use primary care exclusively, those who did had adjusted health-related quality-of-life scores an average of 2.1 points lower for physical health and 3.6 points higher for mental health ( Table 4 ).

|

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to comprehensively assess the clinical and services outcomes characteristics of patients with bipolar disorder who were accessing primary care services exclusively. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that compared with persons who did not use primary care exclusively, those who did were less likely to be diagnosed as having co-occurring psychiatric conditions but more likely to be burdened with general medical conditions, notably cardiovascular disease.

We also found that patients diagnosed as having bipolar disorder who used primary care exclusively had a lower prevalence of psychiatric inpatient use. This finding might be attributed to lesser clinical severity of mental illness, undetected psychiatric comorbidity resulting from primary care providers' lack of knowledge or tools to effectively assess symptoms of mental disorders, or less access to specialty mental health care. However, less than one-third of persons who used primary care exclusively received guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy after the analysis adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical factors, which parallels findings from prior studies ( 28 , 32 ). Although patients with bipolar disorder who were exclusive primary care users had fewer psychiatric symptoms, they also received suboptimal pharmacotherapy, which could lead to poor psychiatric outcomes over time.

General medical outcomes were worse for patients with bipolar disorder who used primary care exclusively. The substantial burden of co-occurring general medical conditions, notably diabetes, among persons with bipolar disorder also exceeded U.S. national trends ( 33 ) and trends in the veteran population ( 34 ). Persons who used primary care exclusively were more physically ill, reflected in a greater likelihood of a medical hospitalization and lower physical health-related quality-of-life scores, consistent with previous research ( 35 ). Many of these medical conditions are increasingly being attributed to side effects of common antimanic medications (second-generation antipsychotics) ( 22 ), making the management of medical conditions among patients with bipolar disorder especially paramount.

Our findings have important implications for the care of patients with bipolar disorder in general, particularly for those who regard primary care as their principal site of health services. Persons with bipolar disorder experience a wide range of functioning and a substantial burden of general medical comorbidity. Because of this, it is not surprising that those with this illness may use primary (general medical) services as their primary site of care. Bipolar disorders have traditionally been seen as a condition exclusively managed in mental health specialty settings, and evidence suggests that patients with bipolar and other mood disorders are increasingly being prescribed second-generation antipsychotics in primary as opposed to specialty mental health care ( 16 , 17 ). Because these medications can exacerbate cardiovascular risk factors, determining how to best manage medical conditions among patients with bipolar and other mental disorders has important policy implications ( 12 , 36 ).

Overall, our results suggest that both mental health and general medical services are inadequate for patients with bipolar disorder. In general, medical care for patients with mental disorders has remained suboptimal ( 37 , 38 , 39 ). Chronic medical conditions among patients with bipolar and other chronic mental disorders may often be missed because the patients are primarily managed in the mental health setting, where their medical illnesses may be overlooked ( 14 ). Conversely, many primary care programs lack sufficient access to mental health expertise required to deal with the more complex psychiatric symptoms ( 13 , 36 ). Patients experiencing poor medical status may not have their psychiatric treatment regimen monitored adequately, leading to decreased adherence and poor behavioral management. Similarly, patients with poor mental health status could be affected by the psychological effects of uncontrolled medical conditions. Hence, creating an optimal care setting for patients with bipolar disorder may require strategies that address gaps in general medical as well as psychiatric care ( 23 ).

There are limitations to this study that warrant consideration. Bipolar disorder diagnoses were based on VA administrative data and not clinician assessment, and administrative data are not reliable in discerning specific bipolar disorder episodes from other psychiatric diagnoses. Mental health symptoms and functioning were not thoroughly assessed, and lack of information on presenting complaints in primary care might have limited our ability to account for explanatory factors of poor outcomes. Although the LHSV survey data contain comprehensive information on patient factors and quality of life that is not available from administrative data, the survey results are more than ten years old and cross-sectional, hence limiting our ability to assess the impact of structural changes to VA services since 1999 and to assess outcomes longitudinally (for example, resolution and recurrence of psychiatric or medical illness).

Primary care use may also have been underestimated, because utilization outside the VA was not ascertained. However, it is unlikely that patients sought mental health services outside the VA because mental health parity was limited in 1999, and these patients primarily relied on the VA for mental health services. In assessing guideline-concordant care, we were limited by a lack of data on dosing, duration of treatment, medication blood levels, concomitant psychotherapy, and other factors associated with appropriate care.

Finally, our study sample (older and predominately male) differs from what is observed outside the VA. Because of the VA's single-payer, highly integrated system, we expected that VA patients with bipolar disorder would be less likely than the general population outside of the VA to rely exclusively on primary care. Hence, although not entirely generalizable to populations outside the VA, our findings may represent a conservative estimate of exclusive primary care use and subsequent poor outcomes among patients with bipolar disorder.

Conclusions

Patients with bipolar disorder treated in primary care settings were more likely than those who received mental health services to have comorbid general medical disorders, and although those treated in primary care settings were less likely to experience poor psychiatric outcomes, they were also less likely to receive guideline-concordant care for bipolar disorder. Even within a highly integrated system of care, such as the VA, patients with bipolar disorder may require additional strategies that address gaps in general medical as well as psychiatric care. In addition, an optimal care setting for patients with bipolar disorder may need to include programs that address gaps in general medical as well as psychiatric care. Because patients with bipolar disorder experience a substantial burden of co-occurring medical conditions that require management in primary care, providing primary care clinicians with additional information and tools to manage medical conditions within the context of bipolar disorder, in combination with mental health specialist support, may be warranted to improve both physical and mental health care for this group.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service, the VA National Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center (grant IIR 07-115), and the National Institute of Mental Health (grants R34 MH74509 and R01 MH79994). The authors acknowledge the VA Office of Quality and Performance for providing access to the data from the Large Health Survey of Veterans. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the VA.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Judd LL, Akiskal HS: The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. Journal of Affective Disorders 73:123–131, 2003Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Wang PS: Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 3:137–158, 2007Google Scholar

3. Goetzel RZ, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, et al: The health and productivity cost burden of the "top 10" physical and mental health conditions affecting six large US employers in 1999. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 45:5–14, 2003Google Scholar

4. Blow FC, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, et al: Care for Veterans With Psychosis in the Veterans Health Administration, FY06: 8th Annual National Psychosis Registry. Ann Arbor, Mich, Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center, 2007Google Scholar

5. Huxley N, Baldessarini RJ: Disability and its treatment in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disorders 9:183–196, 2007Google Scholar

6. Peele PB, Xu Y, Kupfer DJ: Insurance expenditures on bipolar disorder: clinical and parity implications. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1286–1290, 2003Google Scholar

7. Simon GE, Unützer J: Health care utilization and costs among patients treated for bipolar disorder in an insured population. Psychiatric Services 50:1303–1308, 1999Google Scholar

8. Bryant-Comstock L, Stender M, Devercelli G: Health care utilization and costs among privately insured patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders 4:398–405, 2002Google Scholar

9. Kilbourne AM, Brar JS, Drayer RA, et al: Cardiovascular disease and metabolic risk factors in male patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder. Psychosomatics 48:412–417, 2007Google Scholar

10. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW: Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease 3:A42, 2006Google Scholar

11. Kilbourne AM, Ignacio RV, Kim HM, et al: Are VA patients with serious mental illness dying younger? Psychiatric Services 60:589, 2009Google Scholar

12. Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA: From silos to bridges: meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. Health Affairs 25:659–669, 2006Google Scholar

13. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Nossek A, et al: Service delivery in older patients with bipolar disorder: a review and development of a medical care model. Bipolar Disorders 10:672–683, 2008Google Scholar

14. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Locus of mental health treatment in an integrated service system. Psychiatric Services 51:890–892, 2000Google Scholar

15. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

16. Mark TL, Levit KR, Buck JA: Psychotropic drug prescriptions by medical specialty. Psychiatric Services 60:1167, 2009Google Scholar

17. Domino ME, Swartz MS: Who are the new users of antipsychotic medications? Psychiatric Services 59:507–514, 2008Google Scholar

18. Balf G, Stewart TD, Whitehead R, et al: Metabolic adverse events in patients with mental illness treated with antipsychotics: a primary care perspective. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 10:15–24, 2008Google Scholar

19. Correll CU, Frederickson AM, Kane JM, et al: Equally increased risk for metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia treated with second-generation antipsychotics. Bipolar Disorders 10:788–797, 2008Google Scholar

20. Gallo JJ, Zubritsky C, Maxwell J, et al: Primary care clinicians evaluate integrated and referral models of behavioral health care for older adults: results from a multisite effectiveness trial (PRISM-e). Annals of Family Medicine 2:305–309, 2004Google Scholar

21. Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al: Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1455–1462, 2004Google Scholar

22. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:596–601, 2004Google Scholar

23. Smith TE, Sederer LI: A new kind of homelessness for individuals with serious mental illness? The need for a "mental health home." Psychiatric Services 60:528–533, 2009Google Scholar

24. Health Status and Outcomes of Veterans. Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores Veterans SF-36: 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees Executive Report. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Quality Performance, May 2000Google Scholar

25. Skinner KM, Miller DR, Lincoln E, et al: Concordance between respondent self-reports and medical records for chronic conditions: experience from the Veterans Health Study. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 28:102–110, 2005Google Scholar

26. Skinner KM, Miller DR, Spiro A 3rd, et al: Measurement strategies designed and tested in the Veterans Health Study. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 27:180–189, 2004Google Scholar

27. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr: The MOS short-form general health survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care 26:724–735, 1988Google Scholar

28. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 159(Apr suppl):1–50, 2002Google Scholar

29. Bauer MS, Callahan AM, Jampala C, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:9–21, 1999Google Scholar

30. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases 40:373–383, 1987Google Scholar

31. Gordon AJ, Maisto SA, McNeil M, et al: Three questions can detect hazardous drinkers. Journal of Family Practice 50:313–320, 2001Google Scholar

32. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:543–552, 2007Google Scholar

33. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al: Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care 29:1263–1268, 2006Google Scholar

34. Kilbourne AM: The burden of general medical conditions in patients with bipolar disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports 7:471–477, 2005Google Scholar

35. Uebelacker LA, Wang PS, Berglund P, et al: Clinical differences among patients treated for mental health problems in general medical and specialty mental health settings in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. General Hospital Psychiatry 28:387–395, 2006Google Scholar

36. Thielke S, Vannoy S, Unützer J: Integrating mental health and primary care. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 34:571–592, vii, 2007Google Scholar

37. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al: Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1584–1590, 2002Google Scholar

38. Kilbourne AM, Welsh D, McCarthy JF, et al: Quality of care for cardiovascular disease-related conditions in patients with and without mental disorders. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23:1628–1633, 2008Google Scholar

39. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al: Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Medical Care 40:129–136, 2002Google Scholar