Utilization of Emergency Medical Transports and Hospital Admissions Among Persons With Behavioral Health Conditions

Emergency medical services personnel (such as paramedics and emergency medical technicians) work to stabilize individuals who are experiencing medical crises during transport to an emergency department and serve about 18 million patients annually at a cost of $3 billion per year ( 1 , 2 ). In areas where primary care services are scarce, emergency medical services are routinely the only source of care for miles ( 3 ).

Often, emergency medical services personnel are the first contact for persons with behavioral health conditions (mental disorders and substance use disorders) who are experiencing crises in the community. Indeed, 14% (almost 7.5 million) of emergency visits for behavioral health conditions from 1992 to 2001 involved emergency medical services transports (hereafter referred to as transports) ( 4 ). There is concern about medically unnecessary transports and misuse of emergency departments among persons with behavioral health conditions ( 5 , 6 , 7 ); however, the literature regarding transport and emergency department utilization among persons with behavioral health conditions is not well developed and has a number of limitations. For example, mental disorders are too broadly defined and include diagnoses such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, among others, which are not considered to be severe mental illnesses. This inclusive definition of mental disorders likely inflates estimates of the number of persons with mental illness who use transports and emergency departments ( 4 , 5 , 6 ).

Moreover, little is known about demographic differences between general medical and behavioral health-related transports or diagnostic concordance along the continuum of emergency care (that is, from 911 dispatchers to emergency medical services technicians to emergency department physicians). In addition, there is limited information about factors related to hospital admission—a reasonable indicator of appropriate use of emergency care services—among behavioral health transports. Thus it is difficult to identify areas where training might be needed along the continuum or to identify points where, when appropriate, persons with behavioral health conditions could be diverted from the emergency department to other services.

To address these knowledge gaps, this study used linked transport and emergency department data to address the following questions: First, what proportion of behavioral health versus general medical transports results in a hospital admission? Second, what are the demographic differences between general medical and behavioral health transports? Third, for transports associated with behavioral health conditions, what is the concordance of diagnostic impressions along the continuum of emergency care? And, fourth, what factors are related to hospital admission among persons with behavioral health conditions?

Methods

Administrative data on transports and emergency department visits from January 1, 2001, through March 31, 2003, from three counties in a southeastern state were used to compare the characteristics of behavioral health and general medical transports. Also, diagnostic concordance along the emergency care continuum for behavioral health transports was examined. Data providing information about transport and emergency department billing events were merged to create a data set of 70,126 transports to emergency departments.

Transports to nonhospital facilities (N=24,570) and transports that were missing demographic data (N=997) were excluded. In general, transports to nonhospital facilities included interfacility transports, which most often were scheduled nonemergency transports and transports to primary care offices.

Specific details about the three counties in which this study was conducted cannot be provided per data confidentiality agreements. The state in which the study was conducted has a population of about 4.2 million, approximately 65% of which is white, with a median age of approximately 35. In 2000 this state ranked 47th in per capita income and 40th in unemployment rates. About 39.5% of the state's population lived in rural areas ( 8 ).

Study variables included 911 dispatcher and emergency medical technician impression codes, rural or urban pick-up location, patient demographic characteristics, emergency department diagnostic and procedural codes, emergency department visit dates and dispositions, and hospital length of stay. Transports coded as schizophrenia, a mood disorder, a psychotic or delusional disorder, or alcohol or drug abuse or dependence were identified as behavioral health transports.

First, the proportion of transports involving behavioral health conditions was estimated, and hospital admission rates among behavioral health and general medical transports were compared. Next, logistic regression was used to examine differences between general medical and behavioral health transports. Next, the kappa statistic was used to examine diagnostic congruence for behavioral health transports along the continuum of emergency care ( 9 ). Finally, logistic regression was used to examine factors related to hospital admission among behavioral health transports.

This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Results

During the study period, there were a total of 70,126 transports to emergency departments and approximately 12% (8,441) were coded as relating to behavioral health by 911 dispatchers, emergency medical services personnel, or emergency department physicians: 7.1% (N=4,995) were coded as behavioral by 911 dispatchers; 9.8% (N=6,862) were coded as behavioral by emergency medical technicians; and 6.1% (N=4,285) were coded as behavioral by emergency department physicians. With emergency department coding as the standard, 28.9% (N=19,060) of the general medical transports (N=65,841) resulted in a hospital admission, compared with 20% (N=859) of the behavioral health transports (N=4,285), and this was a statistically significant difference ( χ2 =156.77, df=1, p<.001). Also, among transports that resulted in a hospital admission, behavioral health transports resulted in longer hospital stays (mean±SD=8.85±8.53 days) than did general medical transports (6.83±8.78 days; t=-6.77, df=942, p<.001).

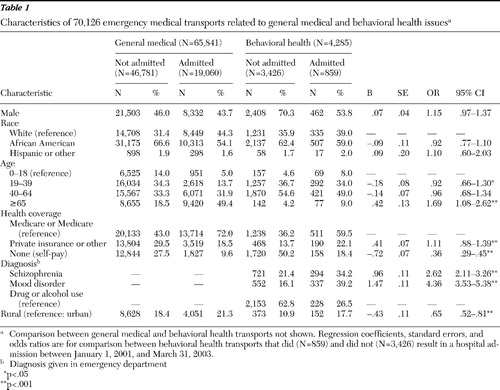

Demographic and clinical characteristics of transported persons are shown in Table 1 . Although results from multivariate analyses are not shown, persons receiving behavioral health transports were more likely than those receiving general medical transports to be male (OR=1.99, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.86–2.13), white (OR=1.40, CI=1.10–1.79), between the ages of 19 and 39 (OR=2.40, CI=2.08–2.78) or 40 and 64 (OR=3.00, CI=2.58–3.42), classified as self-paying (OR=1.16, CI=1.07–1.25), and more likely to be from rural areas (OR=1.62, CI=1.47–1.78). Behavioral health transports were less likely to be covered by Medicaid or Medicare (OR=.86, CI=.80–.93) or private or other types of insurance (OR=.39, CI=.36–.43) and were less likely to be for persons older than age 65 (OR=.31, CI=.26–.38).

|

Behavioral health diagnostic congruence between 911 dispatchers and the emergency department was .58 (CI=.57–.59), congruence between emergency medical technicians and the emergency department was .65 (CI=.64–.66), and congruence between 911 dispatchers and emergency medical technicians was .68 (CI=.67–.69). Among the 4,995 transports coded by 911 dispatchers as behavioral health, emergency medical technicians coded eight out of ten similarly (84.7%, N=4,231). Among the 6,043 transports coded as behavioral health in the emergency department, 73.1% (N=4,420) were coded similarly by emergency medical technicians.

With emergency department coding as the standard, factors related to hospital admission among behavioral health transports were examined (see Table 1 ). Over half (56%) of the behavioral health transports had diagnoses of drug or alcohol use disorders, 21% had a diagnosis of a mood disorder, and 24% had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. However, only 27% of those with drug and alcohol use disorders were admitted to the hospital, compared with 34% of those with schizophrenia and 39% of those with mood disorders. As shown in Table 1 , behavioral health transports of individuals aged 19–39 (OR=.92) were less likely than those for individuals aged 18 or younger to result in hospital admission. However, transports of individuals aged 65 or older were more likely to result in admission (OR=1.69). Compared with transports of Medicaid or Medicare beneficiaries, transports of persons classified as self-paying were less likely to result in admission (OR=.36). Compared with transports of persons with drug or alcohol use disorders, transports of those with schizophrenia were almost three times as likely to result in hospital admission (OR=2.62). Persons transported who had mood disorders were over four times as likely to be admitted (OR=4.36). Transports from rural settings were less likely than transports from more urban settings to result in admission (OR=.65).

Discussion

Findings suggest that individuals with behavioral health conditions made up about 6% of all transports. This percentage is lower than that found in other studies ( 4 , 5 ) and is most likely due to the use in this study of a more restrictive definition of mental illness, the focus on emergency department visits associated with transports versus all emergency department visits, and the uniqueness of the three counties in which the study was conducted.

Definitions of mental illness matter because there are significant differences between persons with adjustment disorders or episodic depression versus those with schizophrenia. Recognizing these differences could have implications for differential responses along the emergency care continuum. A more restricted set of diagnoses was used to identify persons with severe mental illness, which captured persons who were most likely significantly impaired by their disorders. Here, 77% of individuals with schizophrenia and 41% with mood disorders were Medicaid or Medicare beneficiaries; receipt of such benefits is an indicator of illness duration and disability.

Significantly fewer behavioral health transports resulted in a hospital admission compared with general medical transports. In addition, compared with general medical transports, persons with behavioral health transports were more likely to be classified as self-paying (the person had no insurance) and to be from rural areas. These findings likely reflect the scarcity of behavioral health crisis services in rural areas and underscore the need for greater capacity to provide these services.

Moreover, among the behavioral health transports, individuals with schizophrenia were almost three times as likely as persons with drug or alcohol use disorders to be admitted to the hospital. Persons with mood disorders were over four times as likely to be admitted. Substance use disorders accounted for over half of all behavioral health transports; however, just over a quarter of these transports resulted in a hospital admission. These findings are consistent with anecdotal evidence suggesting that the burden on emergency care providers is driven to a large extent by individuals with substance use disorders rather than mental disorders ( 10 ).

The less-than-optimal agreement in diagnosing behavioral health conditions along the continuum of emergency care raises concern ( 11 ). Emergency medical services and emergency department personnel, often fails to recognize persons presenting with behavioral health conditions or to provide psychiatric services when warranted ( 12 , 13 ). Moreover, factors such as the limited effectiveness of substance abuse screening tools used by emergency departments, busy emergency department environments, insufficient training specific to diagnosing behavioral health conditions, and stigma toward uncommunicative or combative patients could further inhibit the delivery of appropriate treatment ( 13 , 14 ).

Could better crisis intervention training and more community-based behavioral health resources and treatment options for emergency medical service personnel reduce inappropriate use of emergency transports and emergency departments? This question is especially salient as the social safety net for persons with behavioral health conditions continues to deteriorate.

Arguably, the emergency medical services system has not responded to its growing role as a de facto provider of behavioral health services with the development and deliberate dissemination of a nationwide training curriculum or behavioral health triage program. Rather, a handful of local emergency medical services agencies have created ad hoc transport and triage protocols to divert behavioral health transports from the emergency department when the problem becomes noticeable ( 10 ). In general, the training provided to these emergency medical technicians is not standardized, and the nature of medical oversight and impact of these ad hoc transport and triage protocols are not well understood. However, better emergency medical services training and triage protocols are only part of the solution. Communities will need to increase their capacity to manage behavioral health crises and increase access to acute care facilities to which persons with behavioral health conditions can be diverted.

These findings are limited to counties with similar demographic profiles and emergency care service availability. Data entry issues may have led to underestimations or overestimations of the true number of behavioral health transports and may have affected results in unknown ways. However, these data are the best currently available to address questions about diagnostic congruence along the emergency care continuum and the characteristics of behavioral health transports.

Conclusions

The emergency medical services system has become a de facto care provider for persons with behavioral health conditions. Research is needed on effective training and triage strategies to reduce inappropriate utilization of emergency medical transports and emergency departments among persons with behavioral health conditions. Moreover, there is a need for more behavioral health crisis services and acute care facilities to which emergency medical services personnel can transport persons with behavioral health conditions.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Patterson is supported by grant KL2 RR024154 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The contents of this brief report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, et al: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 emergency department summary. National Health Statistics Report 6:1–38, 2008Google Scholar

2. Medicare Payments for Ambulance Transports. Report no OEI-05-02-00590. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General, 2006Google Scholar

3. Rural Emergency Medical Services: Special Report. Report no OTA-H-445. Washington, DC, US Congress Office of Technology Assessment, 1989Google Scholar

4. Larkin GL, Claassen CA, Emond JA, et al: Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health conditions, 1992 to 2001. Psychiatric Services 56:671–677, 2005Google Scholar

5. Larkin GL, Claassen CA, Pelletier AJ, et al: National study of ambulance transports to United States emergency departments: importance of mental health problems. Prehospital Disaster Medicine 21(suppl 2):82–90, 2006Google Scholar

6. Brown E, Sindelar J: The emergent problem of ambulance misuse. Annals of Emergency Medicine 22:646–650, 1993Google Scholar

7. Patterson PD, Baxley EG, Probst JC, et al: Medically unnecessary emergency medical services (EMS) transports among children ages 0 to 17 years. Maternal and Child Health Journal 10:527–536, 2006Google Scholar

8. South Carolina Community Profiles. Columbia, South Carolina Office of Research and Statistics, 2008. Available at www.sccommunityprofiles.org . Accessed Mar 31, 2009 Google Scholar

9. Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174, 1977Google Scholar

10. Lelchuk I: 18 months. 362 people. 3,869 ambulance trips. $11.6 million. SF confronts the human and financial costs of repeatedly sending paramedics to help homeless alcoholics. San Francisco Chronicle, Oct 5, 2005, p A1Google Scholar

11. Pointer J, Levitt M, Young J, et al: Can paramedics using guidelines accurately triage patients? Annals of Emergency Medicine 38:268–277, 2001Google Scholar

12. Lowenstein SR, Wieissberg MP, Terry D: Alcohol intoxication, injuries, and dangerous behaviors—and the revolving emergency door. Journal of Trauma 30:1252–1258, 1990Google Scholar

13. Cherpitel C: Screening for alcohol problems in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine 26:158–166, 1995Google Scholar

14. D'Onofrio G, Bernstein E, Bernstein J, et al: Patients with alcohol problems in the emergency department, part 1: improving detection. Academic Emergency Medicine 5:1200–1209, 1998Google Scholar