Competence of Interpreters in a South African Psychiatric Hospital in Translating Key Psychiatric Terms

The importance of good-quality interpreting services in mental health practice is undisputed. There is now a burgeoning literature of increasing sophistication regarding the training and practices of interpreters in mental health settings, although studies have been conducted mainly in high-income countries ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). The issue of linguistic diversity is no less important in low- and middle-income countries. However, few studies have examined the provision of adequate linguistic access in such contexts. Instead, the field has focused far more on the broader politics of health care provision.

In many poorer contexts, ad hoc and haphazard arrangements are made for interpreter services. Not uncommonly, family members or custodial workers in the facility are recruited to interpret. South Africa has a constitutional commitment to nondiscrimination on the basis of language. Public health services are usually staffed, especially at the senior specialist level, by professionals who commonly speak only one or at most two of South Africa's official languages (there are 11 official languages nationally and at least three in each province), and these services do not have formal interpreter posts ( 5 ). The problem stems mainly from the political history of language dominance in the country during apartheid ( 5 , 6 ). The question arises, however, of how language practices operate in public health institutions in contemporary South Africa more than ten years after the transition to democracy.

To address part of this question, we explored the competencies and experiences of individuals who provide informal interpretation services on a daily basis at a large urban psychiatric hospital. Interpreting in the real world is a far more complex task than simply translating from one language into another ( 7 ). However, being able to translate key terms is a necessary condition for adequate interpreting. As a first step, therefore, we examined interpreters' competency in translating key phrases commonly used in psychiatric interviews.

Methods

The study was conducted between May and July 2006. All but one of the individuals who do Xhosa interpreting in the hospital agreed to be interviewed. None of the six participants was in an official interpreter post because such posts do not exist. None did interpreting full-time. All were black South Africans and native Xhosa speakers. Two participants were administrative clerks (women between 35 and 55), two were security guards (one man and one woman, both in their 30s), and two were nurses (one man and one woman, also in their 30s).

In the context of a more broad-ranging interview about interpreting practices, participants translated commonly used psychiatric diagnostic questions from English into Xhosa and then provided back-translations in English of their own translated items. Each participant's translations were then checked by two of 12 independent back-translators, all of whom met the following criteria: speaks Xhosa as a first language, speaks English as a second language, has completed high school, and is not working in or familiar with the mental health field. Individuals working in the mental health field were not suitable because their familiarity with the key diagnostic questions might have influenced their back-translations. All back-translators were black South Africans between the ages of 25 and 40.

No information about the nature of the study was given to the back-translators in order to guard against their using external knowledge of the study to influence their back-translations. As noted, each participant's translations were checked by two independent back-translators in case the back-translators themselves provided idiosyncratic or incorrect back-translations. In addition, no back-translator could check more than one set of translations, because back-translations of any subsequent text could be influenced by exposure to the first text. All independent back-translations were checked by the first two authors, both of whom have studied Xhosa at the university level, as well as by a specialist who had university-level training in Xhosa and in translation skills. Participants' Xhosa translations and back-translations as well as the independent translators' back-translations were then tabulated.

The study was approved by the Committee for Human Research at Stellenbosch University, an institutional review board that is accredited by the National Institutes of Health. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of their rights not to participate or to withdraw at any time.

Results

Exchanges from interviews with the interpreters are presented below to illustrate problems in the translation of psychiatric terms.

Even before the translation exercise began, it became clear that not all interpreters were bilingual—particularly the security guards, both of whom were involved in interpreting on a daily basis at the hospital. They repeated questions and remained quiet until the interviewer explained questions in very basic terms. These two participants, unlike the clerks and nurses, appeared not to understand the questions. Examples of exchanges with one of the security guards are presented below to illustrate.

Interviewer (SK): "What I first want to know from you is how long have you been doing interpreting?"

(No response from the participant.)

SK: "While working, I know you are not a professional interpreter, but for how long have they been asking you to do the interpreting?"

Participant (P1): "The first time now I interpret. Are you asking about the job?"

SK: "Would you encourage other people that work here or wherever to do interpreting?"

P1: "When interpreting to the patients?"

SK: "Ja, would you encourage other people to do that?"

(No response from the participant.)

SK: "Would you maybe say to them, 'Yes, I think I would tell them to do interpreting' or 'No.' Out of your experience?"

P1: "No, the doctor inform me why he call me."

Although a basic understanding of psychiatric concepts is essential for adequate interpreting, psychiatric knowledge among interpreters was poor in many instances. The following exchanges with the two security guards illustrate confusion about key psychiatric terms.

SK: "Can you give me just your explanation or definition of depression?"

P1: "Depression is like when you feel that something hurts you or something that you are not clear about that makes you angry."

SK: "Mm-hm."

P1: "Then you don't know what the outcome, you don't have the solution of this. And then it is stuck in your mind, and it makes your head ache, and then you can't cope just leave it like that."

SK: "And your definition or understanding of psychosis?"

P1: "Psychosis?"

SK: "Ja."

P1: "What is that thing?"

SK: "It is when someone is, or psychotic, have you heard of that?"

P1: "Mm."

SK: "So, what do you understand by psychotic?"

P1: "Ok, I then, as I told I just have little bit of basic."

SK: "Ja, no, I'm not looking for a right or wrong answer. I just want to know how you understand it."

P1: "Ok, I understand when the patient is psychotic because sometimes he can say just imagining and then you must understand there is sometimes the mind that she is thinking and not the mind she have before. It's just the other mind now."

SK: "Ok."

P1: "What's going on to the head it's just up in the head, in her head."

SK: "Ok and your definition of mania. Have you heard of mania?"

P1: "No."

SK: "Ok, I just want your definition. I am not looking for a direct academic definition, but what is your understanding of depression?"

P2: "Uh, depression is like feeling sad."

SK: "Ok."

P2: "At a specific time."

SK: "Ok."

P2: "Ja, it's just feeling sad at a specific time."

SK: "Ok and your definition of psychosis?"

P2: "Psychosis is just a—how can I say it—for me it's a thought disorders."

SK: "Ok and mania. If someone is manic?"

P2: "When the person is like feeling like childish things."

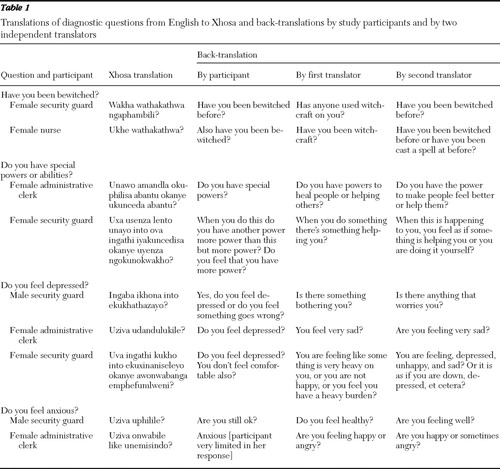

Most participants gave literal translations of the following diagnostic questions: Do you hear voices? Are you afraid that people want to hurt or poison you? Do you feel sad? Have you been bewitched? Although the literal translations were adequate in some cases, some participants used different questions, words, or phrases in addition to or to replace the original diagnostic questions, which we discovered by looking at back-translations by the participants and by the independent translators. Examples are provided in Table 1 .

|

Although this study did not have a formal method of assessing overall interpreter competence, it was clear that at least three of the six participants (the male nurse and the two security guards) would experience major difficulties in interpreting interviews conducted in Xhosa and English. The male nurse discussed a strategy of denial he used when he felt that he was not interpreting accurately: "Because sometimes you feel that you did not convey this thing `lekker' [well] to the patient or to the doctor. Then you think `Jislaaik' [goodness me]. Ok but then you keep it to yourself. You just let it go. You don't worry about this."

Discussion

This study was limited in scope and did not address the full spectrum of issues related to interpreting. Some of the difficulties with the translations in our study reflected more general, well-established challenges in translating psychiatric terms such as depression ( 8 ). These issues aside, however, it appears that only half of the interpreters were probably competent to do the job of interpreting. Half were not fully bilingual, and none had the necessary training and skills to act as professional interpreters, let alone in the demanding context of psychiatric care, which places extra demands on the interpreter ( 9 ). The two security guards seemed to face particular challenges.

Competent interpreters with training and skills reduce communication problems and increase patient comprehension ( 10 ). Untrained individuals may frequently provide inaccurate interpretations. Experienced psychiatrists who work with interpreters have suggested that a good interpreter should be competent in two or more languages, familiar with the patient's culture, and knowledgeable about clinical psychiatry, which helps reduce cognitive and emotional distortions ( 8 ). At best, half of the study participants met the above requirements; more stringent assessment of competence might have led to less positive results.

The lack of training may have resulted in the interpreters' liberal use of literal translations. Literal translation loses the connotative function of terms, a loss that is crucial in psychiatry, as is the loss of context in literal translation ( 9 ). For interpreters to be able to interpret both denotatively and connotatively and to make appropriate use of context, they need to be well trained and highly competent in at least two languages and preferably to have used both languages for a number of years ( 3 ).

As noted above, problems of language equivalency force interpreters to use additional or alternative words. Often there is no Xhosa word that is equivalent to the English word. One participant mentioned that there is no direct translation of the words "anxiety" and "depression." Thus interpreters must use additional or substitute words to convey the meaning of the English words. Additional and substitute words are sometimes necessary and even useful to eliminate misunderstandings resulting from health professionals' jargon, which patients often find difficult to understand ( 11 ). Translating jargon into words that the patient can understand requires some sophistication and linguistic skill.

Without the necessary training and skills, interpreters' use of additional or alternative questions can distort the original meaning. For example, the question "Are you feeling uncomfortable?" does not convey the same meaning as "Do you feel depressed?" Similarly, "Are you still ok?" is not an adequate substitute for "Do you feel anxious?"

Conclusions

It is clear that not all persons who claim to be bilingual are competent in both languages, and being competent in a second language does not qualify a person to act as an interpreter. To provide accurate interpreting services in mental health settings, interpreters must be trained in interpreting and in psychiatry. The lack of adequate language services at the study hospital is not the result of a faulty language policy. It is clearly stated in the Western Cape Language Policy that a member of the public may use any one of the three official languages of the Western Cape in his or her communication with any institution of the provincial or local government ( 12 ). The lack of adequate language services is the result of ineffective implementation and monitoring of the policy, and without effective implementation the policy means little for individuals in need of psychiatric care.

The question arises of how this state of affairs can continue more than ten years after South Africa's transition to democracy. The study findings could be interpreted as evidence of discrimination against people with mental disorders. However, it appears that this problem is not unique to mental health care and occurs across a wide range of health services ( 13 ). Clearly, questions need to be raised about the extent to which patient rights are being realized in South Africa. We have reported these findings to the study hospital, which may use them in negotiations about language access with the relevant government department. We are also planning a training program for interpreters and clinicians.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors are grateful to Stellenbosch University Research Committee for financial support, to the participants for their help, and to the hospital for permitting them to undertake this work.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hsieh E: Interpreters as co-diagnosticians: overlapping roles and services between providers and interpreters. Social Science and Medicine 64:924–937, 2007Google Scholar

2. Putsch RW: Cross-cultural communication: the special case of interpreters in health care. JAMA 254:3344–3348, 1985Google Scholar

3. Westermeyer J: Working with an interpreter in psychiatric assessment and treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 178:745–749, 1990Google Scholar

4. Woloshin S, Bickell NA, Schwartz LM, et al: Language barriers in medicine in the United States. JAMA 273:724–728, 1995Google Scholar

5. Swartz L: Culture and Mental Health: A Southern African View. Cape Town, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

6. Drennan G: Psychiatry, post-apartheid integration and the neglected role of language in South African institutional contexts. Transcultural Psychiatry 36:5–22, 1999Google Scholar

7. Bot H: Dialogue Interpreting in Mental Health. Amsterdam, Editions Rodopi BV, 2005Google Scholar

8. Marcos LR: Effects of interpreters on the evaluation of psychopathology in non-English speaking patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:171–174, 1979Google Scholar

9. Swartz L, Turner G: The interpreter as colleague: a model for mental health interpreting. Presented at a Multicultural Mental Health Australia workshop, Melbourne, 2006Google Scholar

10. Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, et al: Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Services Research 42:727–755, 2007Google Scholar

11. Diaz-Duque OF: Overcoming the language barrier: advice from an interpreter. American Journal of Nursing 82:1380–1382, 1982Google Scholar

12. Western Cape Language Policy. Cape Town, South Africa, Western Cape Department of Culture and Sport, 2008Google Scholar

13. Levin ME: Different use of medical terminology and culture-specific models of disease affecting communication between Xhosa-speaking patients and English-speaking doctors at a South African paediatric teaching hospital. South African Medical Journal 96:1080–1084, 2006Google Scholar