Perceived Barriers to Mental Health Treatment in Metropolitan China

Recent psychiatric epidemiologic surveys using different methodologies have yielded different estimates of the prevalence and distribution of mental disorders in China ( 1 ). However, they have uniformly demonstrated very high levels of unmet need for treatment in both urban and rural areas. Phillips and colleagues ( 2 ) found that 8.2% of people in China with past-month mental disorders received health care over their lifetime. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey in Beijing and Shanghai likewise found that 12.4% of respondents with past-year mental disorders received any health care within the 12 months before the interview ( 3 ). These two surveys respectively found that only 2.9% and 4.9% of respondents received help from mental health specialists ( 2 , 3 ). However, the reasons for underutilization of treatment have not been examined empirically. We therefore studied the barriers to initiating mental health treatment in Beijing and Shanghai.

Methods

This study is part of the WMH Survey Initiative and used version 3.0 of the WMH Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for assessment ( 3 , 4 ). It was based on a multistage clustered area probability sample of household-dwelling adults aged 18–70 in Beijing (N=2,633) and Shanghai (N=2,568). The 5,201 face-to-face interviews were administered by trained lay interviewers at respondents' homes between November 2001 and February 2002. The response rates were 75% in both cities.

Psychiatric diagnoses based on the WMH-CIDI exhibited satisfactory concordance with diagnoses generated by the Chinese Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV ( 3 ). Part I of the interview schedule was completed by all respondents (N=5,201). Part I assessed core disorders, including anxiety disorders (panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and social phobia), mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder), alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence with abuse. Part II of the interview schedule involved questions about risk factors, assessments of additional disorders (drug abuse and dependence, posttraumatic stress disorder, conduct disorder, and separation anxiety disorder), and treatment barriers. All part I respondents who met criteria for having at least one disorder (N=437) and a 25% probability subsample of other part I respondents (N=1,191) received part II of the interview schedule (N=1,628). A weight was used for the part I sample to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households and for differences in intensity of recruitment effort among hard-to-recruit respondents. A second weight of 4.0 (1/.25) was applied to adjust for the 25% of part I respondents who did not meet diagnostic criteria but were selected as a part II subsample.

Respondents were categorized as having severe mental illness if they had any of the following: a past-year diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, any past-year psychiatric diagnosis and a suicide attempt in the past 12 months, having substance dependence with physiological symptoms, or one or more past-year diagnosis with high levels of impairment on the Sheehan Disability Scale ( 5 ). Respondents were considered to have moderate psychiatric disorders if they had at least one disorder and a moderate level of impairment as measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale ( 5 ) or if they had substance dependence without physiological signs. The remaining respondents with any past-year disorder were categorized as having mild psychiatric disorders.

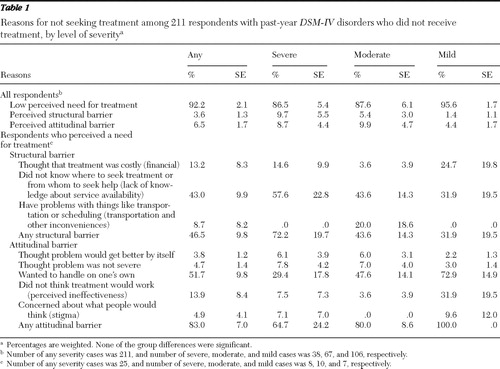

Part II respondents who reported no use of health services (from medical doctors, psychologists, counselors, herbalists, acupuncturists, or any other healing practitioners) were asked whether there was a time during the past 12 months that they felt that they might have needed to see a professional for problems with their emotions, nerves, or mental health. Respondents who endorsed such need were asked about barriers to treatment: three structural barriers and five attitudinal barriers ( Table 1 ).

|

The reasons for not initiating treatment were compared between those with a disorder who were not receiving treatment and the total part II subsample; reasons were also compared among subgroups defined by disorder severity. The differences in the proportion endorsing each reason among the three severity subgroups were evaluated using chi square tests.

Results

Among 1,628 part II respondents, 211 met the criteria for a past-year mental disorder but had not used services in the past year. The weighted rate of low perceived need for treatment was 92%. A greater proportion of respondents with mild psychiatric disorders (96%) reported low perceived need for treatment than those with severe (87%) and moderate (88%) psychiatric disorders. The proportions reporting structural barriers in the severe, moderate, and mild groups decreased from 72%, 44%, to 32%, respectively, whereas the proportions reporting attitudinal barriers increased from 65%, 80%, to 100%, respectively. Respondents with severe psychiatric disorders who perceived a need for treatment were more likely to report structural barriers (72%) than attitudinal barriers (65%). They also endorsed lack of knowledge about service availability (58%) as the most common structural barrier. Psychiatric stigma, which was endorsed by only 5% of those who perceived a need for treatment, was not a common barrier ( Table 1 ).

Discussion

Previous psychiatric epidemiologic surveys in China typically have not considered treatment rates. The few recent studies that examined treatment rates did not examine the types of treatment barriers. Although our study should be of interest to both policy makers and future researchers, the following limitations are worthy of note. The WMH-CIDI in the study presented here may underestimate the prevalence of mental disorders for methodological reasons ( 1 , 4 ). The number of respondents who reported need for treatment was too small to render statistical power to our analysis. Examination of how treatment barriers varied by specific type of mental disorder must await data from future surveys with larger samples or higher prevalence estimates ( 6 ). Our survey did not include psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, although they remain very important for policy and service planning in China. The reasons for low perceived need could vary among individuals, and the three groups of barriers studied were overlapping. Future studies that incorporate qualitative methods may clarify how responses such as "treatment was costly," "problem would get better by itself," and "problem was not serious" interact.

A key step to reducing the underutilization of treatment of mental disorders is to understand why affected individuals do not seek treatment. Western studies have documented various barriers, including lack of perceived need for treatment ( 6 ), stigma ( 7 ), pessimism regarding treatment ( 8 ), lack of access because of financial barriers ( 9 ), and other structural barriers ( 6 ). While suggesting a similarly diverse range of treatment barriers, our study indicated that low perceived need for treatment was very common. Future research is needed to clarify reasons for low perceived need for treatment in the context of China's ongoing health care reform.

The differences in distribution of treatment barriers by psychiatric disorder severity were expected. Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, they pointed to the increasing importance of structural barriers relative to attitudinal barriers as mental disorders became more severe. The finding that lack of knowledge about service availability was the most common barrier among respondents with severe disorders might be partly methodological in origin. The WMH-CIDI probed help seeking for "problems with emotions, nerves, or mental health." Because these terms were psychologically loaded, respondents with low mental health literacy might fail to report treatment sought from traditional practitioners for physical symptoms that accompany mental disorders. Nonetheless, we believe that low availability of service is a significant cause of undertreatment. For example, only 2.3% of the health care budget in China was allocated to mental health in 2002, even though neuropsychiatric diseases constituted over 17.0% of disability-adjusted life years ( 4 ). Economic reform, privatization of health care, and market failures in China have rendered health service increasingly inaccessible and unaffordable, particularly for persons with low incomes ( 10 ).

Conclusions

Our findings argue for prioritization of resources for mental health services and the need for public mental health education. Given China's size and heterogeneity, a single best-practice model is nearly impossible. Successful reform must consider regional strengths, constraints, and infrapolitics. Thus the central government's recent call to provide psychiatric services in tertiary general hospitals is inadequate. These hospitals are thinly scattered in the cities and nonexistent in rural areas where undertreatment is severe. At present, there are only 1.27 psychiatric physicians per 100,000 people in China ( 11 ). These physicians vary widely in training and mostly focus on psychosis in their clinical work. Mental health care reform should therefore involve both specialist and nonspecialist sectors, involve training of primary care workers, and promote early access to basic mental health treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The Chinese WMH Survey Initiative is supported by the Pfizer Foundation in conjunction with the World Health Organization WMH Survey Initiative. The authors thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (grant R01-MH070884), the Mental Health Burden Study (contract HHSN271200700030C), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the U.S. Public Health Service (grants R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01-DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (grant FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Glaxo-SmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Sanofi-Aventis.

Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Kaiser Permanente, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst. He has served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly and Company and Wyeth-Ayerst, and he has had research support from Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Yang LH, Link BG: Comparing diagnostic methods for mental disorders in China. Lancet 373:2002–2004, 2009Google Scholar

2. Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, et al: Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet 373:2041–2053, 2009Google Scholar

3. Huang YQ, Liu ZR, Zhang MY, et al: Mental disorders and service use in China; in The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Edited by Kessler RC, Üstün TB. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2008Google Scholar

4. Lee S, Guo WJ, Tsang A, et al: Impaired role functioning and treatment use of mental disorders and chronic physical disorders in metropolitan China. Psychosomatic Medicine 71:886–893, 2009Google Scholar

5. Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, et al: Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 27:93–105, 1997Google Scholar

6. Sareen J, Jagdeo A, Cox BJ, et al: Perceived barriers to mental health service utilization in the United States, Ontario, and the Netherlands. Psychiatric Services 58:357–364, 2007Google Scholar

7. Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Houston TK, et al: Attitudes and illness factors associated with low perceived need for depression treatment among young adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:746–754, 2006Google Scholar

8. Bayer JK, Peay MY: Predicting intentions to seek help from professional mental health services. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 31:504–513, 1997Google Scholar

9. Mojtabai R: Trends in contacts with mental health professionals and cost barriers to mental health care among adults with significant psychological distress in the United States: 1997–2002. American Journal of Public Health 95:2009–2014, 2005Google Scholar

10. Tang S, Meng Q, Chen L, et al: Tackling the challenges to health equity in China. Lancet 372:1493–1501, 2008Google Scholar

11. Zheng LQ: A study of the status of mental health service in China [in Chinese]. Hospital Management Forum 25:28–30, 2008Google Scholar