Quality of Diabetes Care for Underserved Patients With and Without Mental Illness: Site of Care Matters

At least 20.6 million people aged 20 years and older in the United States live with diabetes—it is a leading cause of death annually ( 1 ). Because diabetes is common and costly ( 2 ) and has devastating consequences for an individual's health ( 3 , 4 ), several national organizations have published clinical guidelines for optimal diabetes care ( 5 , 6 ). Despite widespread dissemination of these guidelines, many studies have shown that effective primary and secondary preventive treatments are not received. Up to one-third of Americans with diabetes are unaware that they have it ( 7 , 8 ). Even when diagnosed, community-based insured populations receive only 45% of the care indicated ( 8 ).

Patients with a diagnosis of a mental illness, such as schizophrenia, have twice the prevalence of diabetes as the general population (15%–18% versus 7%) ( 1 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ). Persons with mental illness may be vulnerable to receiving reduced quality of care ( 13 ). There are conflicting conclusions as to whether there are disparities in the quality of diabetes care between persons with and without mental illness. Goldberg and colleagues ( 14 ) found that among patients in community-based clinics, patients with mental illness were significantly less likely than patients without mental illness to receive preventive diabetes services ( 14 ). In a population of insured managed care patients, Jones and colleagues ( 15 ) found that patients with mental illness were less likely to have glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) or cholesterol levels checked. However, rates of dilated eye exam and urine protein testing were similar ( 15 ). Frayne and colleagues ( 16 ) used administrative claims and survey data from the Veterans Health Administration to show that patients with mental illness were less likely than patients without a mental health condition to have an HbA1c test, a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) check, or an eye examination.

However, other studies in the Veterans Health Administration found no difference in the receipt of HbA1c testing ( 17 , 18 ), LDL testing ( 17 ), or foot examinations ( 18 ). The authors attributed these findings to the observation that patients with a diagnosis of mental illness had higher rates of health care use than patients without such a diagnosis ( 17 , 18 ).

Most previous studies have included managed care and veteran populations. Less is known about the quality of diabetes preventive services for patients with mental illness in safety-net health systems. The quality of diabetes care in these settings is relevant to patients with mental illness because these patients are more likely to be of lower socioeconomic status, unemployed ( 19 ), and city dwelling ( 20 ). Safety-net hospitals serve patients with these characteristics, making study of this setting germane ( 21 ).

The quality of diabetes care in safety-net hospitals and other low-income populations has been inconsistent in the general population ( 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ). In a study of outpatient clinics in the United Kingdom, patients with the lowest incomes were less likely than the most affluent to receive HbA1c testing, blood pressure measurements, retinal screening, or nephropathy assessment ( 25 ). Other studies have demonstrated that diabetes preventive services are comparable in lower and higher socioeconomic groups ( 26 , 27 , 28 ).

Limited access to outpatient primary care physicians for low-income patients served by safety-net hospitals may contribute to poor glycemic control ( 29 ). When patients are unable to attain appointments in outpatient clinics or cannot afford transportation to their provider, they often resort to using emergency rooms and urgent care centers as their primary health care provider ( 30 , 31 ). Patients with mental illness are significantly less likely than those without a mental disorder to have a primary care physician ( 32 ). The purpose of this study was to determine whether patients with mental illness receive care in a safety-net health system that is comparable to that received by patients without mental illness and to determine the degree to which poor quality of diabetes care among persons with or without mental illness is a function of where they received that care.

Methods

Participants

Adult patients at a large urban public hospital were eligible for inclusion in this study. Study patients were included if they were between the ages of 18 and 75, had diabetes diagnosis codes, and had an outpatient or inpatient encounter between January 2004 and December 2005. Once enrolled, patients were followed through December 2006. Patients were identified using diagnosis codes from administrative data and the hospital's diabetes registry. Patients were defined as having diabetes if they had two outpatient or emergency department diagnosis codes for diabetes at least one day apart, had one inpatient diagnosis code for diabetes, or were already in the diabetes registry. Patients were included if they did not have a death code during the study period and had a diabetes diagnosis and a diabetes-related laboratory workup completed in at least one of the first two quarters of 2004. Any one test of urine albumin and creatinine, HbA1c, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), LDL, cholesterol, triglycerides, or urine creatinine was considered a diabetes-related laboratory workup and was sufficient to gain entry into a quarter. To remain in the study, a participant must have had at least two visits, with the last visit at least six months later than the first. Administrative data were used to gather basic demographic information and determine the presence of comorbid conditions. The project was reviewed and approved by Emory University's institutional review board and the hospital's Research Oversight Committee.

Measures

Primary outcome. The primary outcome of this study was receipt of preventive diabetes care, as defined by the Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures ( 5 , 33 ). The study measured the proportion of patients who received each of the five outcome measures in a given year: LDL test, HDL test, HbA1c test, nephropathy test, and dilated eye exam. Data on receipt of blood pressure measurements were unavailable.

Mental illness. Patients with mental illness were identified by using administrative diagnosis codes. Patients with at least one primary or secondary diagnosis during the study period of a psychotic disorder ( ICD-9 codes 295.00–295.99) or a mood disorder ( ICD-9 codes 296.00–296.99) were classified as having mental illness.

Site of care. Patients received care in a large urban hospital that serves predominantly uninsured (36%), Medicaid (18%), and Medicare (39%) patients. Patients who present to the emergency department are triaged to either the emergency department or the urgent care center. These patients were said to receive care in an emergency setting. The hospital manages a large primary care center with outpatient clinics within the hospital and in the community. Patients call in advance to make an appointment. These patients were said to receive care in an outpatient setting.

Covariates. Comorbid conditions were identified by diagnosis codes present in the administrative data. A diagnosis of hypertension ( ICD-9 codes 401–405), hyperlipidemia ( ICD-9 codes 125 and 272.1–272.4), or obesity ( ICD-9 code 278) noted at anytime during the study was considered a comorbid condition for that patient. Heart disease, stroke, renal disease, and peripheral vascular disease that were present at the initial visit or happened within six months of the initial visit were also considered to be comorbid conditions. Demographic variables included gender, age, race (defined as African American or non-African American), and presence of any insurance.

Statistical analysis

For each demographic characteristic and study outcome, we first calculated the frequency and percentage of participants with each dichotomous demographic characteristic. Second, we calculated the mean and standard deviation of the continuous demographic variables and checked the data for values out of the plausible range. Third, we compared demographic characteristics and receipt of recommended services between patients with and without mental illness using the chi square test for dichotomous variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Groups were compared with the pooled t test for equal variances and the Satterthwaite t test for unequal variances. Fourth, we compared the proportion of patients with and without mental illness who received each recommended service for each year of the study, so our results would be comparable to other published studies of annual receipt of diabetes services. Fifth, we compared the entire population of patients who received care solely in the emergency department or urgent care center during the entire study with patients who saw an outpatient clinic primary care physician at least once during the study period. Sixth, within the groups of patients with and without any outpatient visits we also compared demographic characteristics and receipt of preventive services between patients with and without mental illness. Seventh, we selected risk factors cited in the literature to include in a multivariable logistic regression model to examine the relationship between having a mental illness and receipt of appropriate diabetes preventive care.

Because receipt of care in the emergency setting appeared to be an intervening variable in the relationship between having a diagnosis of mental illness and receipt of preventive diabetes services, multivariable logistic regression models were also stratified by location of care. The adjusted multivariable analyses controlled for gender, age, race, insurance status, and the number of comorbid conditions. We also analyzed an adjusted multivariable model that included location of care and an interaction term between mental illness and location of care. Finally, we analyzed a multivariable model with mental illness and location of care but without an interaction term to assess the magnitude of effect of each variable. All analysis was done with SAS, version 9.2.

Results

Initially, 9,215 adult patients with diabetes seen in the enrollment window were identified for this study. Of those, 8,817 patients (96%) had an additional visit at least six months later, making them eligible for the study sample.

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the study population. Patients were more likely to be female (64%) and African American (90%). The mean age of the population was 55 years. Among those who had some insurance (63%), the vast majority were on public assistance—either Medicare (39%) or Medicaid (18%). Most patients had comorbid hypertension (95%) and hyperlipidemia (75%). Ten percent of the study population (N=908) had a diagnosis of a mental illness. Of these, 506 (56%) had an ICD-9 code of 295–295.9 (indicating psychotic disorder). Compared with patients without mental illness, those with mental illness were significantly younger (p<.001) and more likely to have insurance (p<.001). Patients with mental illness had fewer comorbidities (p=.002) and were less likely to be African American (p<.001).

|

Table 2 presents the proportion of patients with and without a mental illness who received each of the quality indicator services for each year of the study. There was little consistent difference in receipt of services between patients with and without a mental illness. Overall rates of annual testing for both groups averaged 66% for HDL, 63% for LDL, 73% for HbA1c, 60% for nephropathy, and 24% for eye exams.

|

As shown in Table 3 , patients who received care in the outpatient setting were more likely to be older (p< .001) and female (p< .001) and have multiple comorbidities (p<.001). They were less likely to have a mental illness (p<.001). Patients who received care in the outpatient setting and the emergency setting were similar in terms of race and type of insurance. Patients seen in the outpatient setting were significantly more likely than those seen in the emergency setting to receive all HEDIS process measures (p<.001).

|

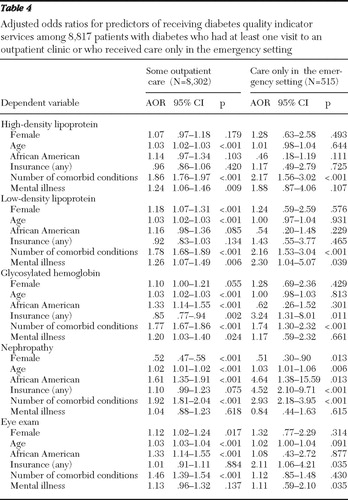

As shown in Table 4 , adjusted analyses showed that among patients who were seen only in emergency services those with mental illness were 2.3 times as likely as those without a mental illness to receive an LDL test during the study. Receipt of any of the other diabetes preventive services among persons who were seen only in emergency services was not significantly different for patients with mental illness and those without mental illness. In the outpatient care setting, patients with mental illness were 1.2 times as likely to receive an HDL, LDL, and HbA1c test as patients without mental illness. Increasing number of comorbid conditions significantly increased a person's odds of receiving almost all diabetes preventive services across mental illness diagnosis and practice setting.

|

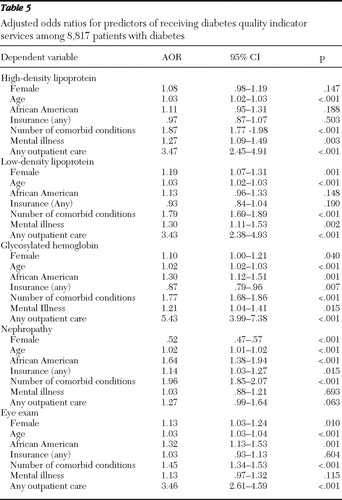

Table 5 presents the adjusted multivariable logistic regression analysis with the location of care included in the model. Diabetic patients who received outpatient care were 3.47 times as likely as diabetic patients seen only in the emergency setting to receive an HDL test, 3.43 times as likely to receive an LDL test, 5.43 times as likely to receive an HbA1C test, and 3.46 times as likely to receive an annual eye exam. Diabetic patients with any outpatient care were 1.27 times as likely as diabetic patients seen only in the emergency setting to receive nephropathy testing, although this finding was not significant (p=.063). Diabetic patients with a diagnosis of mental illness were significantly more likely than those without mental illness to receive HDL, LDL, and HbA1C testing, but the measure of effect was of smaller magnitude than that for location of care.

|

Discussion

All diabetic patients seen only in the emergency setting, irrespective of coexisting mental illness, were dramatically less likely than diabetic patients ever seen in an outpatient setting to receive preventive diabetes services. Diabetic patients with mental illness were significantly more likely to be seen only in the emergency department. Within the outpatient setting, diabetic patients with a diagnosis of mental illness were significantly more likely to have their HDL, LDL, and HbA1c checked each year than diabetic patients without a mental illness.

This study is the first to investigate the quality of care for patients with diabetes and mental illness in a safety-net hospital. It suggests that the treatment setting is a far more important factor in quality of care than mental illness status and that persons with mental illness derive similar benefits from outpatient care as persons without mental illness. The findings are consistent with those of other investigators who found an association between glycemic control and site of care ( 29 ). Using a national sample, Mainous and colleagues ( 34 ) demonstrated that patients who self-reported having no usual source of care had significantly worse glycemic control compared with patients who reported having a usual site of care, usual provider of care, or both.

Targeting all patients with diabetes who are seen only in the emergency setting and intervening to aid them in navigating the outpatient primary care health system may be a reasonable approach to improving the quality of diabetes care. Systems factors in safety-net hospitals that can facilitate receipt of care in the outpatient setting include improving the availability and cost of appointments and transportation and expanding the hours of service of primary care clinics ( 34 ). For example, case managers who organize patient transportation, call with appointment reminders, and individualize strategies to address barriers to access have improved glycemic control in low-income populations in California ( 35 ). Others have recommended having printed patient education materials, dieticians, and exercise counselors readily available to patients ( 36 ).

The rates of HbA1c testing were lower in this study than in national data or studies of patients with private health insurance or veterans' benefits. In our sample, 73% of patients received an HbA1c test in any given year of the study (2004–2006). By contrast, the National Committee for Quality Assurance found that 78% of Medicaid, 87% of Medicare, and 88% of commercial health insurance enrollees with diabetes had their HbA1c tested in 2006 ( 5 ). Rates of HbA1c testing in other studies that investigated patients with mental illness were between 83% and 97% ( 14 , 16 , 18 ). The discrepancy may be partly explained by the fact that our sample was of lower socioeconomic status than other study populations and thus at increased risk of receiving reduced quality of diabetes care ( 25 ).

In one study that analyzed data from six different U.S. safety-net public hospital systems, rates of HbA1c testing at least once over a two-year period varied from 67% to 99% ( 22 ). Other studies of indigent populations also found a wide range of variability in receipt of HbA1c testing (<50% to >90% of patients) ( 27 , 28 , 36 ). Thus the rates of HbA1c testing in our study are consistent with other studies of indigent populations. Rates of LDL testing on average for any given year (63%) were slightly lower than in other nationwide samples (69%–93%) ( 5 , 14 , 16 ), presumably for similar reasons.

This study had a few limitations. First, the use of administrative data and ICD-9 codes to identify patients with mental illness may underestimate the prevalence of mental illness ( 37 ). This study used inpatient and outpatient codes to identify patients with mental illness, thereby maximizing the chances of identifying everyone with mental illness in this study. Outpatient codes correspond best to mental health visits, whereas inpatient diagnosis codes tend to underestimate actual rates of psychiatric comorbidities ( 38 ). In our study, 10% of patients had a mental illness, compared with 6% ( 39 ), 24% ( 18 ), and 25% ( 16 ) in similar studies. Another limitation of administrative claims data is that services that are not billable, such as some forms of nephropathy testing, are less likely to appear in the data. Dilated eye examinations were more expensive in this health system than in the community, so individuals may have obtained this test in another setting.

Finally, the data did not provide information regarding patients' connection to mental health clinics, which are administratively distinct. Patients with a mental illness who receive regular mental health services may have improved access to the outpatient care setting, enabling them to receive more diabetes preventive services. In our study, outpatients with mental illness received more preventive services than outpatients without mental illness, which could also be explained by the additional benefit of mental health services, although further research is needed to establish this connection.

Conclusions

Diabetes preventive services were comparable for diabetic patients with and without mental illness. However, diabetic patients with mental illness were more likely to receive care in the emergency setting, and all diabetic patients seen only in the emergency setting received fewer diabetes preventive services. This study suggests that the treatment setting was a far more important factor in quality of care than mental illness status and that diabetic persons with mental illness derived similar benefits from outpatient care as diabetic persons without mental illness. Future studies should address facilitating access to primary care for diabetic persons with mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The Woodruff Health Sciences Center supported this study through a grant to the Predictive Health Initiative. The authors thank Emily O'Malley, M.S.P.H., for her contributions to this study.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: United States, 2005. Atlanta, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005. Available at apps.nccd.cdc.gov/ddtstrs/template/ndfs_2005.pdf Google Scholar

2. Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, et al: The evolving diabetes burden in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 140:945–950, 2004Google Scholar

3. Barzilay JI, Spiekerman CF, Kuller LH, et al: Prevalence of clinical and isolated subclinical cardiovascular disease in older adults with glucose disorders: the cardiovascular health study. Diabetes Care 24:1233–1239, 2001Google Scholar

4. National Diabetes Statistics, 2007. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Available at diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/index.htm Google Scholar

5. The State of Health Care Quality: 2007. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2007. Available at www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Publications/Resource%20Library/SOHC/SOHC_07.pdf Google Scholar

6. American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 26(suppl 1):S33–S50, 2003Google Scholar

7. McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al: The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 348:2635–2645, 2003Google Scholar

8. Spann SJ, Nutting PA, Galliher JM, et al: Management of type 2 diabetes in the primary care setting: a practice-based research network study. Annals of Family Medicine 4:23–31, 2006Google Scholar

9. Bushe C, Holt R: Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry: Supplement 47:S67–S71, 2004Google Scholar

10. Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J, et al: Incidence, prevalence, and surveillance for diabetes in New York State psychiatric hospitals, 1997–2004. Psychiatric Services 57:1132–1139, 2006Google Scholar

11. Expert group: "schizophrenia and diabetes 2003" expert consensus meeting, Dublin, 3–4 October 2003: consensus summary. British Journal of Psychiatry: Supplement 47:S112–S114, 2004Google Scholar

12. Ryan MCM, Collins P, Thakore JH: Impaired fasting glucose tolerance in first-episode, drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:284–289, 2003Google Scholar

13. Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al: Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:565–572, 2001Google Scholar

14. Goldberg RW, Kreyenbuhl JA, Medoff DR, et al: Quality of diabetes care among adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58:536–543, 2007Google Scholar

15. Jones LE, Clarke W, Carney CP: Receipt of diabetes services by insured adults with and without claims for mental disorders. Medical Care 42:1167–1175, 2004.Google Scholar

16. Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, et al: Disparities in diabetes care: impact of mental illness. Archives of Internal Medicine 165:2631–2638, 2005.Google Scholar

17. Krein SL, Bingham CR, McCarthy JF, et al: Diabetes treatment among VA patients with comorbid serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57:1016–1021, 2006.Google Scholar

18. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al: Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1584–1590, 2002.Google Scholar

19. Aro S, Aro H, Keskimaki I: Socio-economic mobility among patients with schizophrenia or major affective disorder: a 17-year retrospective follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:759–767, 1995Google Scholar

20. McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, et al: A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology. BMC Medicine 2:13, 2004Google Scholar

21. Werner RM, Goldman LE, Dudley RA: Comparison of change in quality of care between safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. JAMA 299:2180–2187, 2008Google Scholar

22. Chew LD, Schillinger D, Maynard C, et al: Glycemic and lipid control among patients with diabetes at six US public hospitals. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 19:1060–1075, 2008Google Scholar

23. Goldman LE, Vittinghoff E, Dudley RA: Quality of care in hospitals with a high percent of Medicaid patients. Medical Care 45:579–583, 2007Google Scholar

24. Ross JS, Cha SS, Epstein AJ, et al: Quality of care for acute myocardial infarction at urban safety-net hospitals. Health Affairs 26:238–248, 2007Google Scholar

25. Hippisley-Cox J, O'Hanlon S, Coupland C: Association of deprivation, ethnicity, and sex with quality indicators for diabetes: population based survey of 53,000 patients in primary care. BMJ 329:1267–1269, 2004Google Scholar

26. Brown AF, Gregg EW, Stevens MR, et al: Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and quality of care for adults with diabetes enrolled in managed care: the translating research into action for diabetes (triad) study. Diabetes Care 28:2864–2870, 2005Google Scholar

27. Maizlish NA, Shaw B, Hendry K: Glycemic control in diabetic patients served by community health centers. American Journal of Medical Quality 19:172–179, 2004Google Scholar

28. Suwattee P, Lynch JC, Pendergrass ML: Quality of care for diabetic patients in a large urban public hospital. Diabetes Care 26:563–568, 2003Google Scholar

29. Rhee MK, Cook CB, Dunbar VG, et al: Limited health care access impairs glycemic control in low income urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 16:734–746, 2005Google Scholar

30. Ansell D, Schiff R, Goldberg D, et al: Primary care access decreases nonurgent hospital visits for indigent diabetics. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 13:171–183, 2002Google Scholar

31. Felland LE, Hurley RE, Kemper NM: Safety Net Hospital Emergency Departments: Creating Safety Valves for Non-urgent Care. Issue brief 120. Washington, DC, Center for Studying Health System Change, May 2008Google Scholar

32. Bradford DW, Kim MM, Braxton LE, et al: Access to medical care among persons with psychotic and major affective disorders. Psychiatric Services 59:847–852, 2008Google Scholar

33. Saaddine JB, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, et al: Improvements in diabetes processes of care and intermediate outcomes: United States, 1988–2002. Annals of Internal Medicine 144:465–474, 2006Google Scholar

34. Mainous AG 3rd, Koopman RJ, Gill JM, et al: Relationship between continuity of care and diabetes control: evidence from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. American Journal of Public Health 94:66–70, 2004Google Scholar

35. California Medi-Cal Type 2 Diabetes Study Group: Closing the gap: effect of diabetes case management on glycemic control among low-income ethnic minority populations. Diabetes Care 27:95–103, 2004Google Scholar

36. Rosal MC, Benjamin EM, Pekow PS, et al: Opportunities and challenges for diabetes prevention at two community health centers. Diabetes Care 31:247–254, 2008Google Scholar

37. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al: Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Medical Care 40:129–136, 2002Google Scholar

38. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE: Variations in the associations between psychiatric comorbidity and hospital mortality according to the method of identifying psychiatric diagnoses. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23:317–322, 2008Google Scholar

39. Sullivan G, Han X, Moore S, et al: Disparities in hospitalization for diabetes among persons with and without co-occurring mental disorders. Psychiatric Services 57:1126–1131, 2006Google Scholar