Reductions in Arrest Under Assisted Outpatient Treatment in New York

For persons with a diagnosis of serious mental illness, arrest and subsequent incarceration disrupt continuity of care and community-based tenure. Often, these individuals are arrested for minor offenses, such as disturbing the peace or public intoxication; far less common are serious violent crimes ( 1 ). Behaviors underlying these offenses may be associated with psychiatric instability, substance use, homelessness, poverty, and criminogenic factors ( 2 , 3 ). Regardless of the reasons for arrest or the underlying causes of behavior, involuntary outpatient commitment may represent a less coercive intervention than arrest and incarceration for persons with serious mental illness who are at risk of criminal justice involvement.

Previous research has shown that many adults with serious mental illness cycle through jails. In a recent study of five Maryland and New York jails, 14.5% of male inmates and 31.0% of female inmates had current serious mental illness ( 4 ). A 2002 five-site survey found that approximately 50% of consumers in public-sector psychiatric outpatient clinics reported being arrested at some point in their lives ( 5 ). Because reasons for the higher arrest and subsequent incarceration rates in this population are complex ( 6 ), interventions designed to reduce criminal justice involvement need to focus on systems of care (such as improving access to effective psychiatric and substance abuse treatment and psychosocial services) and on individual behaviors (such as increasing adherence to prescribed treatment) ( 7 , 8 ).

New York State's assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) program, and the intensive services provided under the program, could decrease criminal justice involvement for adults with serious mental illness. AOT is court-mandated treatment designed for individuals who are unlikely to live safely in the community without supervision and who are also unlikely to voluntarily participate in treatment. The court order stipulates that intensive case management services must be provided to individuals while they are in the AOT program. Under an alternative arrangement, some individuals for whom an AOT order is pursued in court sign a voluntary service agreement in lieu of a formal court order. Under a voluntary agreement, the individual is directed to the same array of services as those who receive an AOT order; however, the individual signs a statement that he or she will adhere to a prescribed community treatment plan rather than receiving a mandate from the court.

The goal of both AOT and voluntary agreements is to improve access and adherence to intensive behavioral health services. If these approaches are successful, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that arrest rates would decrease. A previous study of involuntary outpatient commitment in North Carolina found that outpatient commitment lasting six months or longer was associated with significantly reduced risk of arrest among individuals with a history of multiple hospitalizations and prior arrests or acts of violence ( 9 ).

This study analyzed data from a sample of individuals with serious mental illness in six counties across New York State. Its purpose was to determine whether individuals had lower arrest rates when receiving AOT or voluntary enhanced services than before initiating either.

Methods

This project was approved by the institutional review boards of Duke University, Policy Research Associates, the New York State Office of Mental Health, and Biomedical Research Alliance of New York.

Participants were sampled from AOT program rosters of mental health service recipients in six New York counties. Eligible individuals were aged 18 or older and had a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or an affective disorder. Structured interviews were conducted from February 2007 to October 2008 with 211 eligible individuals who had qualified for AOT services and who were either recipients of AOT or had signed a voluntary service agreement, as reported by local AOT coordinators. Of the 211 interviewees, 181 had either received court-mandated AOT (N=139) or had signed a voluntary service agreement (N=42) at some point during the study period. The remaining 30 eligible individuals received only usual care services and thus were excluded from this analysis.

Demographic data were collected during the interviews, and diagnostic data were extracted from matched Medicaid claims files. Arrest records for the 181 participants from November 1, 1999, to February 28, 2008, were obtained from the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services.

A dummy variable was constructed to indicate whether study participants had been arrested during any given month. Analytic comparison groups of person-month observations were constructed to reflect status in regard to AOT or a voluntary agreement. Because some individuals received AOT and had a voluntary agreement at different time points (that is, they initially undertook a voluntary agreement but later moved to AOT), a single category of observations—pre-AOT and pre-voluntary agreement—was used as the reference group for comparison. This category included all person-months before an individual either received AOT or signed a voluntary agreement. Thus five groups of observations were compared: pre-AOT and pre-voluntary agreement; current AOT; current voluntary agreement; post-AOT, which comprised person-months for individuals whose AOT orders had expired, including those who previously had a voluntary agreement that was followed by AOT; and post-voluntary agreement, which comprised person-months for individuals whose voluntary agreement had expired and who had no history of AOT.

The primary diagnosis in the Medicaid claims data was reclassified into four categories—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and other. Voluntary agreements were relatively uncommon and were used almost exclusively in the upstate regions of New York. That is, the four upstate counties (Albany, Erie, Monroe, and Nassau) provided virtually all of the voluntary agreements, whereas the downstate, New York City area (New York and Queens Counties) provided the majority of AOT orders. To adjust the data to account for this distribution, the multivariable analyses controlled for region. Other covariates included race and ethnicity, age, and sex.

The data were structured as one unit of observation per person, per month over the 100-month study period. There were 9,229 person-months available for analysis—pre-AOT and pre-voluntary agreement (N=7,097), current AOT (N=1,094), current voluntary agreement (N=468), post-AOT (N=361), and post-voluntary agreement (N=209). We estimated repeated-measures, multivariable logistic regression models (SAS, version 9.1) to predict the odds of arrest by AOT and voluntary agreement status, with the models controlling for time and nonindependence of observations.

Results

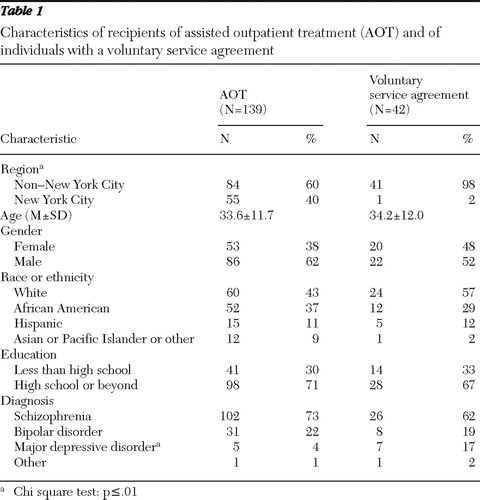

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the sample. Compared with individuals who had received AOT, a larger proportion of individuals with a voluntary agreement and no AOT had a primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder (4% compared with 17%) and resided in regions outside New York City (60% compared with 98%). No significant differences between groups were found in age, gender, race or ethnicity, and education.

|

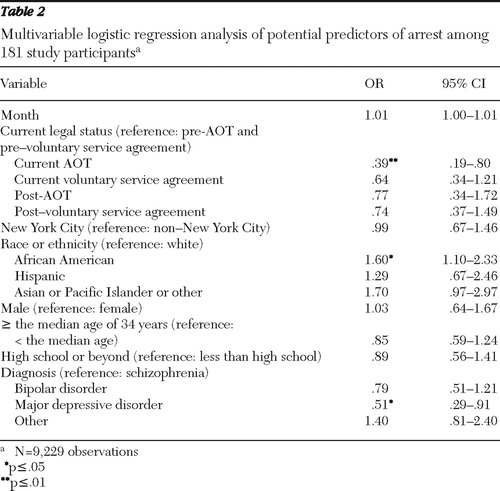

Table 2 displays results of the logistic regression analysis. Odds of arrest in any given month for participants who were currently receiving AOT were nearly two-thirds lower than odds for participants in the pre-AOT and pre-voluntary agreement group (the reference group) (OR=.39, p<.01). No statistically significant difference in odds of arrest was detected between those with a current voluntary agreement and those in the reference group. The adjusted predicted probabilities of arrest in any given month were 3.7% for individuals who had not yet initiated AOT or a voluntary agreement, 1.9% for individuals currently on AOT, and 2.8% for individuals currently under a voluntary agreement. Furthermore, odds of arrest for those in the post-AOT group and the post-voluntary agreement group were not significantly different than for those in the reference group. Holding legal status and other covariates constant, odds of arrest were significantly higher for African Americans for whites (OR=1.60, p<.05) and significantly than for participants with major depressive disorder than for those with schizophrenia (OR=.51, p<.05).

|

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the odds of arrest among AOT recipients in the sample were relatively low while they were enrolled in the program. Possible reasons are increased engagement in intensive case management services, including ongoing supervision and monitoring of behavior, and increased adherence to appropriate psychotropic medications. The absence of a significant difference in odds of arrest for participants who were currently under a voluntary agreement, which also involves close oversight and intensive care services, may suggest that the court order conferred additional benefits not found with a voluntary agreement.

One explanation for a unique effect of the AOT mandate may be that AOT recipients were more strongly motivated to engage in treatment to avoid negative consequences of violating the court order. If so, improved treatment motivation and engagement in intensive case management could have been mediating factors in the relationship between AOT and reduced odds of arrest. However, studies of assertive community treatment and intensive case management, which were the primary treatment models in the AOT program and voluntary agreements, either have not detected an association with reductions in arrests ( 10 , 11 , 12 ) or have yielded mixed results ( 13 ).

The lack of a clear association between intensive services and arrest rates may suggest that the court order's mechanism of effect goes beyond services utilization per se and may involve the law enforcement system's altered approach in dealing with court-ordered individuals who commit low-level offenses. For example, arresting police officers may be more likely to refer known AOT participants back to the mental health system instead of arresting them for nuisance crimes, whereas their non-AOT counterparts—without the perceived leverage of a court order in place—might be arrested and booked for the same offenses. Additional research is needed to assess the direct and interactive effects on arrest outcomes of different types and intensity of services utilization by individuals receiving AOT and those with a voluntary agreement.

Limitations of this study include a small sample and nonrandomized study groups. Without the benefits of a randomized trial, it is possible that there were unmeasured, systematic differences between individuals in the study conditions or even within individuals as they moved across study conditions (that is, from pre-AOT and pre-voluntary agreement status to an AOT order), which could have biased our effect estimates. Also, voluntary agreement cases were clustered predominantly in upstate counties. Any unmeasured influences on odds of arrest across regions that were not captured in our region control variable could have biased effect estimates. Other than region and proportion with major depressive disorder, there were no significant differences in measured characteristics between participants who received AOT and who had voluntary agreements, which mitigates the potential for selection bias.

Presence of a comorbid substance use disorder could have had an important influence on individuals' odds of arrest, but no common, time-invariant or time-dependent measures were available to validly account for that effect in the analysis. However, unless having a comorbid substance use disorder operated differently among participants currently receiving AOT than among those in the pre-AOT and pre-voluntary agreement group, the bias from this omitted variable would not distort comparisons in odds of arrest between the two groups.

Also, we were limited to measuring treatment participation on the basis of AOT enrollment and of voluntary agreement status because data on actual treatment engagement (that is, types and intensity of services utilization) were not available for this analysis. Patterns of service utilization may have had a meaningful influence on participants' odds of arrest. Data on actual treatment engagement might have partly explained the absence of effect for the voluntary agreement group, as well as for the post-AOT and post-voluntary agreement groups if utilization of services affected odds of arrest and if exiting either of these service conditions was associated with reductions in utilization.

It is also possible that an effect in the post-AOT group could have been detected if the analysis had been stratified by duration of AOT, because evidence indicates that longer periods of AOT are associated with better treatment outcomes ( 14 ). However, the data were not stratified because the small sample limited statistical power.

Conclusions

These findings add important information about potential benefits of involuntary outpatient commitment for people with serious mental illness who are unlikely to live safely in the community without supervision. Existing evidence indicates that avoiding involuntary hospitalizations and interpersonal strife is more important to people with serious mental illness than avoiding outpatient commitment ( 15 ). For those at high risk of criminal behavior, AOT may actually be a far less coercive alternative than cycling through the criminal justice system.

Our evidence suggests that AOT may reduce the risk of being arrested. Averted arrests may translate into lower rates of incarceration for people with serious mental illness at high risk of criminal behavior—who are already overrepresented in the corrections system. AOT may thus play an important role in improving community-based treatment outcomes for persons with serious mental illness and in reducing coercion associated with criminal justice involvement in this population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study is funded by the New York State Office of Mental Health, with additional support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of numerous individuals in collecting, synthesizing, and reporting the data for this effort. At Policy Research Associates, they thank Wendy Vogel, M.P.A., Roumen Vesselinov, Ph.D., Jody Zabel, Steven Hornsby, L.M.S.W., and Amy Thompson, M.S.W. They also acknowledge the extensive reviews and critical feedback provided by the MacArthur Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment, which served as an internal advisory group to the study. Although the findings of the study are solely the responsibility of the authors, they gratefully acknowledge the support and assistance of the New York State Office of Mental Health in completing the report, including Steve Huz, Ph.D., Chip Felton, M.S.W., Peter Lannon, Susan Shilling, J.D., L.C.S.W., Qingxian Chen, Michael F. Hogan, Ph.D., Bruce E. Feig, and Lloyd I. Sederer, M.D.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Fisher WH, Roy-Bujnowski KM, Grudzinskas AJ Jr, et al: Patterns and prevalence of arrest in a statewide cohort of mental health care consumers. Psychiatric Services 57:1623–1628, 2006Google Scholar

2. Lamb HR, LE Weinberger: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492, 1998Google Scholar

3. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–572, 2002Google Scholar

4. Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, et al: Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatric Services 60:761–765, 2009Google Scholar

5. Monahan J, Redlich AD, Swanson J, et al: Use of leverage to improve adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Psychiatric Services 56:37–44, 2005Google Scholar

6. Morabito MS: Horizons of context: understanding the police decision to arrest people with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58:1582–1587, 2007Google Scholar

7. Lamberti J: Understanding and preventing criminal recidivism among adults with psychotic disorders. Psychiatric Services 58:773–781, 2007Google Scholar

8. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: A randomized controlled trial of outpatient commitment in North Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:325–329, 2001Google Scholar

9. Swanson J, Borum R, Swartz M, et al: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce arrests among persons with severe mental illness? Criminal Justice and Behavior 28:156–189, 2001Google Scholar

10. Calsyn R, Yonker R, Lemming M, et al: Impact of assertive community treatment and client characteristics on criminal justice outcomes in dual disorder homeless individuals. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health 15:236–248, 2005Google Scholar

11. Bond G, Drake R, Mueser K, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141–159, 2001Google Scholar

12. Mueser K, Bond G, Drake R, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37–73, 1998Google Scholar

13. Loveland D, Boyle M: Intensive case management as a jail diversion program for people with a serious mental illness: a review of the literature. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 51:130–150, 2007Google Scholar

14. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, et al: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce hospital recidivism? Findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1968–1975, 1999Google Scholar

15. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, et al: Assessment of four stakeholder groups' preferences concerning outpatient commitment for persons with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1139–1146, 2003Google Scholar